Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”114628″ img_size=”large”][vc_column_text]In the wake of George Floyd’s murder and the resultant global Black Lives Matter protests, it has been clearer than ever before that the voices of some are prioritised to the exclusion of others.

As part of Banned Books Week 2020 – an annual celebration of the freedom to read – Index is partnering with the Royal Society of Literature, the British Library and English PEN, bringing together a panel of writers who have committed to sharing their stories, to creating without compromise, and to inspiring others to do the same. We ask what ‘freedom’ means in the culture of traditional publishing, and how writers today can change the future of literature.

Urvashi Butalia is Director and co-founder of Kali for Women, India’s first feminist publishing house. An active participant in India’s women’s movement for more than two decades, she holds the position of Reader at the College of Vocational Studies at the University of Delhi.

Rachel Long is a poet and founder of Octavia Poetry Collective for Womxn of Colour, based at the Southbank Centre. Her first collection My Darling from the Lions, shortlisted for the Forward Prize for Best Collection 2020, explores the intersections of family, love, and sexual politics. She is co-tutor on the Barbican Young Poets programme.

Elif Shafak is an award-winning British-Turkish novelist, whose work has been translated into 54 languages. She is the author of eighteen books; her latest, 10 Minutes 38 Seconds in this Strange World, was shortlisted for the Booker Prize and the 2020 RSL Ondaatje Prize. She holds a PhD in political science and she has taught at various universities in Turkey, the US and the UK. She was elected an RSL Fellow in 2019.

Jacqueline Woodson is the author of more than two dozen award-winning books. She is a four-time National Book Award finalist, a four-time Newbery Honor winner, a two-time NAACP Image Award winner, a two-time Coretta Scott King Award winner, recipient of the 2018 Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award, the 2018 Children’s Literature Legacy Award and the 2020 Hans Christian Andersen Award.

Public tickets can be booked through the British Library (£5).[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”114627″ img_size=”large”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Banned Books Week is an annual event celebrating the freedom to read.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text][/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

The heroine of The Little Maid, Viola, is an eight-year-old Ugandan girl who lives with her destitute grandmother and dreams of going to school. Instead, she is sent to live with her aunt, who promises to pay her school fees if Viola works for her first. Viola becomes a maid, forced to wash clothes, scrub the bathroom, cook and live in servants’ quarters. But every day when her cousins’ tutor arrives, she crawls underneath the dining room table to eavesdrop on the lessons. Eventually Viola learns to read and write and escapes the clutches of her evil aunt, who is found guilty of child abuse and child slavery and ordered to school her niece.

The heroine of The Little Maid, Viola, is an eight-year-old Ugandan girl who lives with her destitute grandmother and dreams of going to school. Instead, she is sent to live with her aunt, who promises to pay her school fees if Viola works for her first. Viola becomes a maid, forced to wash clothes, scrub the bathroom, cook and live in servants’ quarters. But every day when her cousins’ tutor arrives, she crawls underneath the dining room table to eavesdrop on the lessons. Eventually Viola learns to read and write and escapes the clutches of her evil aunt, who is found guilty of child abuse and child slavery and ordered to school her niece.

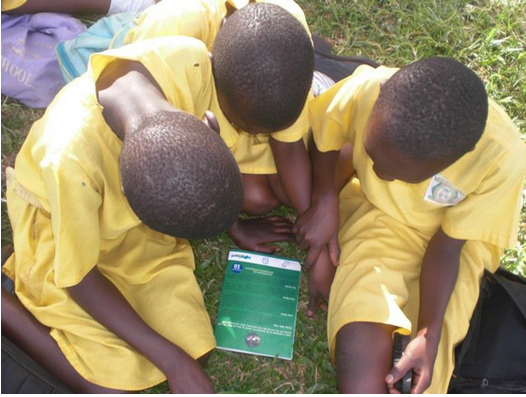

It could be a true story. In Uganda there are an estimated 2.75 million children engaged in work, although not many of those will have the happy ending. But The Little Maid is a work of fiction, written by Oscar Ranzo, a Ugandan social worker turned author who has penned five children’s books. Now, The Little Maid is being distributed to schools across the country low-cost (5,000 Ugandan shillings or $1.90 each) through his Oasis Book Project. The project aims to improve the reading and writing culture in Uganda and provide school-children with entertaining but educational stories to which they can relate. Ranzo sells most of his books to schools, with the proceeds used to publish more titles. However, he also donates copies to more impoverished areas.

In 1969, Professor Taban Lo Liyong, one of Africa’s best-known poets and fiction writers, declared Uganda a ‘literary desert’. “What we want to do with this project is create an oasis in the desert,” explains Ranzo. “That’s why I called it the Oasis Book Project.”

Excluding textbooks, there are only about 20 books published in Uganda annually. According to a study last year by Uwezo, an initiative aimed at improving competencies in literacy and numeracy among children aged six to sixteen years in East Africa, more than two out of every three pupils who had finished two years of primary school failed to pass basic tests in English, Swahili or numeracy. For children in the lower school years, Uganda recorded the worst results.

Growing up in the 1970s and 1980s, Ranzo was privileged to have a grandfather who had a library and attended a private school that held an after class reading session. He was a particularly avid fan of Enid Blyton’s Famous Five series.

“But Mum was a nurse and she wanted me to be a doctor. I wanted to pursue literature and she told me ‘no you can’t do that’, so I did sciences,” says Ranzo, stressing that literature, which remains optional in secondary school, is not taken seriously in Uganda.

Furthermore, many local publishers do not see writing fiction as profitable. “They’d rather publish textbooks and get the government to buy them,” Ranzo explains.

His books are available in two central Kampala bookshops for 8,000 shillings ($3). But in the past 15 months fewer than 20 have moved from the shelves, while he has sold over 3,000 to 20 schools in three districts.

Saving Little Viola, his first book in which the female protagonist, Viola, was introduced, was published in 2011 by NGO Lively Minds. The story ends with Viola being saved by her best friend from two men who want to use her for a ritual sacrifice. UNICEF funded its distribution to 36 primary schools across Uganda as part of a child sacrifice awareness programme.

The primary aim of the Oasis Book Project is to encourage reading, although Ranzo admits he would like people to discuss his stories, which have themes close to his heart. Children being forced into work, the theme of The Little Maid, is something he has witnessed himself.

“Many kids are brought from villages to work as maids in homes in towns or cities, and the treatment they are subjected to is terrible in many cases,” says Ranzo.

His next book, The White Herdsman, which will be released in 2014, deals with the impact of oil production on communities, a timely subject for Ugandans with oil production expected to start in 2016. The book tells the story of a village where water in the well has turned black after an oil spill. A witchdoctor blames the disaster on an albino child.

Ranzo’s stories have been welcomed at Hormisdallen Primary, a private school in Kamwokya, Kampala. English teacher Agnes Kasibante, speaking to Think Africa Press, praises the book’s impact. “It’s actually a big problem in Uganda, most children don’t know how to read. At least those books give them morale to continue loving reading,” she says.

Ranzo has also penned Cross Pollination, a collection of fictional stories for adults about the spread of HIV in a community. According to a recent report, Uganda may not meet its target to increase adult literacy by 50% by 2015.

“I’ve worked in a big multinational company where people have jobs but they can’t write. Reading can help develop this,” says Ranzo, who is currently attending the University of Iowa’s 47th annual International Writing Program (IWP) Fall Residency.

Jennifer Makumbi, 46, a Ugandan doctoral student at Lancaster University, is one of a new generation of Ugandan authors. She won the Kwani Manuscript Project, a new literary prize for unpublished fiction by Africans, for her novel The Kintu Saga. She said Taban Lo Liyong’s description of Uganda as a literary desert was “heartbreaking, especially as in the 1960s Uganda seemed to be poised to be a leading literary producer”.

“But perhaps it is exactly this description that is pushing Ugandans to write in the last ten years,” she continues. “Yes, we have not caught up with West Africa yet but… there are quite a few wins.” In recent years, two female Ugandan authors, Monica Arac de Nyeko and Doreen Baingana, won the Caine Prize for African Writing and the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize respectively. Makumbi’s Kwani prize adds her to a list of eminent Ugandan authors.

Makumbi is optimistic about the future of Ugandan literature: “These I believe are indications that Uganda is on its way.”

The film of Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children is set to be released on 1 February. If the team behind the movie adaptation is at all nervous about screening the film they have good reason. Rushdie, who wrote the screenplay, and has been the literary face for freedom of expression for years, has a tumultuous history of censorship with India.

The Booker prize-winning book is about two children, born at the stroke of midnight as India gained its independence. Their lives become intertwined with the life of this new country.

One of the figures in the book, The Widow, was based on former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. In the book, the character, through genocide and several wars, helps destroy Midnight’s Children. Gandhi had imposed a widely-criticised State of Emergency in India.

In an interesting turn of events, Gandhi threatened Rushdie libel over a single line. That line suggested that Gandhi’s son Sanjay had accused his mother of bringing about his father’s heart attack through neglect. Rushdie settled out of court, and the single line was removed from the book.

The movie adaptation of Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children

The real controversy that followed, the one that changed Rushdie’s life completely, came after the 1988 release of his book The Satanic Verses. While the Iranian supreme leader Ayatollah Khomeini had issued a fatwa against Rushdie and called for his execution (citing the book as blasphemous), the author saw many countries, including India, indulge in their own brand of censorship.

As has been revealed in Rushdie’s memoir Joseph Anton, the author felt the Indian government banned his book without much scrutiny. The Finance Ministry banned the book under section 11 of the Customs Act, and in that order stated that this ban did not detract from the literary and artistic merit of his work. Rushdie, appalled at the logic penned a letter to the then prime minister of India, Rajiv Gandhi, stating:

Apparently, my book is not deemed blasphemous or objectionable in itself, but is being proscribed for, so to speak, its own good… From where I sit, Mr Gandhi, it looks very much as if your government has become unable or unwilling to resist pressure from more or less any extremist religious grouping; that, in short, it’s the fundamentalists who now control the political agenda.

Rushdie was right, of course. Years later, in 2007, he attended the first Jaipur Literary Festival in India unnoticed. Without any security or fuss, he arrived unannounced, mingling with the crowd. Things had changed dramatically by 2012, when Rushdie’s arrival to the now must-attend literary festival was much publicised, and predictably attracted controversy.

Maulana Abul Qasim Nomani, vice-chancellor at India’s Muslim Deoband School, called for the government to cancel Rusdie’s visa for the event as he had annoyed the religious sentiments of Muslims in the past. (Incidentally, Rushdie does not need a visa to enter India as he holds a PIO — “Person of Indian Origin” — card.)

The controversy escalated quickly, with the organisers first attempting to link Rushdie via video instead of having him physically present, but then cancelling the arrangement when the Festival came under graver physical threat. It was a sad day for freedom of expression in India, especially considering the fact that many, including Rushdie felt these moves were politically motivated because of upcoming elections in Uttar Pradesh, where the Muslim vote is very important. The government vehemently denied these claims.

Liberals in India were shocked at the illiberal values that the modern India state espoused, feigning to not be able to protect a writer and a festival against the threats of protestors. Shoma Chaudhary of Tehelka wrote:

The trouble is nobody any longer knows what Rushdie was doing in The Satanic Verses: neither those who are offended by him, nor those who defend him. Almost no one, including this writer, was given a chance to read the book.

Later in the year, initial press reports around Midnight’s Children revealed that the film could not find a distributor in India. The production team thought it might be a case of self-censorship as the film featured a controversial portrayal of Indira Gandhi. However, PVR Pictures, a major distributor in India, has plans to release the film in the country in February 2013.

31 years after the Midnight’s Children hit the stands, and the same year as he was bullied into cancelling a visit to a literary festival, it seems Salman Rushdie will yet again challenge Indian society. It remains to be seen if he will, yet again, become a pawn in the internal politics of the country.

An urgent appeal from Chinese writer Yan Lianke to the General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party and the Chinese Prime Minister

Esteemed General Secretary and Prime Minister:

I am a writer and a university professor. Before deciding to write this letter to you, my conscience was buffeted by a storm of hesitation. It was your encouraging and heartfelt speech, General Secretary, delivered a week ago at the opening ceremony of the Eighth National Congress of the Chinese Writers’ Association that has emboldened me to report to you about the forced eviction and demolition of homes that I have witnessed.

Three years ago, I bought a property in Flower City World Garden using royalties from my books and borrowed money. In July this year, 39 families in the compound, including mine, were formally given eviction notices because of the road-widening project on Wanshou Road in Beijing. A few days after receiving the eviction notices, the wall of our compound was demolished at dawn.

Having been told the eviction was for the development of Beijing, the residents initially were cooperative. However, the Demolition and Relocation Office told the residents that regardless of the size or value of their properties, the compensation per household was set at 500,000 yuan, approximately US$ 78,000, and that whoever cooperated would be further awarded 700,000 yuan. Since then, there has been growing discontent among the residents with the local government and the demolition crew. You can imagine how the conflict and confusion surrounding the forced eviction was intensified by quarrels, fighting, theft and bloodshed.

In August this year, the Demolition and Relocation Office stopped mentioning the 700,000 yuan incentive and instead offered each household a one-off compensation package of 1.6 million yuan, or approximately US$250,000. At the same time, the office initiated a countdown to the demolition.

I visited the Demolition and Relocation Office three times and spoke to the person in charge. During each visit, I made it clear that as a citizen, a writer and a university lecturer, I would take the lead and vacate my property to support the development of Beijing. However, as a citizen whose property is about to be demolished, I requested to view the official documents relating to the road-widening project. I simply wanted to know a few things: how much of the residential zone would be required for the road-widening and how many properties would really need to be demolished. I wanted to know how the compensation was calculated and why the compensation was set at a flat 1.6 million yuan rather than based the area of the properties. In short, all I wanted to see was that the demolition process would more or less follow government regulations and legal procedures and that property owners would be provided with some information. The response I received was along the lines of “everything has already been decided by higher authorities” and “it’s confidential”.

Other residents also made numerous trips to city and district governments to appeal and seek resolution through legal channels but for various reasons the local courts declined to hear the case.

On 24 November, things took an even more bizarre turn. The government of Huaxiang in Fengtai District issued a document to all owners who had received eviction notices. The document stated that on 23 September, law enforcement officials discovered houses with no registered occupants as well as houses without their addresses registered with local authorities. Therefore, these houses were deemed illegal structures and would be forcibly demolished at 8 am on the 30th of November. (In fact, Flower City World Garden has existed for six years.)

I went to the compound this morning where I saw crowds of people and groups of uniformed men and many vehicles blocking access. I saw banners hanging in front of all the houses facing demolition proclaiming, “We pledge to sacrifice our blood and lives to defend our homes!” I saw emotional residents who were indeed ready to sacrifice their lives.

No one knew what would happen during a forced demolition. No local government official was there to mediate with the residents. It appeared that blood could be shed at any moment in this game of cat-and-mouse—if not today, then surely tomorrow. Many residents are determined to live and die with their homes.

Esteemed General Secretary and Prime Minister, as a citizen who is about to lose his home, as a university lecturer and a well-known writer, I have to say this was a shocking scene to witness and experience for myself. The administrators of the People’s University of China where I am employed also attempted to communicate on my behalf with the local government. They were told that the demolition must proceed. You can imagine the distress felt by residents who have nowhere else to go.

As a Chinese citizen, I love my country dearly. As a writer, I am willing to give all I have to promote Chinese culture. As a university professor, I hope to see my students able to study and grow up in a loving and harmonious environment. It is because of my foolish dream of bearing the weight of our nation on my shoulders that I am writing this urgent appeal to you.

I hope the local government will stop playing this game of cat-and-mouse with people whose houses they want to demolish.

I hope this matter can be resolved in a timely manner, in a more rational and a humane way.

I hope all parties will learn from this incident, so that in future there will be fewer farcical forced demolition cases like this, and the Chinese people will live a more dignified life, as Premier Wen frequently stresses.

I hope Chinese people—citizens of China—are given more access to information and can enjoy a greater sense of security and happiness.

My apologies for taking up your time.

Sincerely yours,

Yan Lianke

30 November, 2011