29 Aug 2019 | Egypt, News and features, Volume 48.02 Summer 2019, Volume 48.02 Summer 2019 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Laugh and the World Laughs with Me is an intimate short story of a young woman who has a schizophrenic brother, set against the backdrop of the Tahrir Square demonstrations, from Egyptian writer Eman Abdelrahim. An extract of this new short story was first published in the summer issue of Index on Censorship magazine. Many of her tales often touch upon taboo subjects like mental health and presents women’s dilemmas in surreal ways. Her main influences when writing stems from Russian greats like Anton Chekhov, Nikolai Gogol and Fyodor Dostoevsky. She says she sees parallels between Egyptian society today and 19th century Tsarist Russia.

Laugh and the World Laughs with Me

By Eman Abdelrahim

The three of them are sitting now watching Al Jazeera on the TV. New events are occurring incessantly. No one trusts what is being said. The father asks Shadi to take his medicine, as the time for that has come round. Shadi goes to his desk. He keeps the strip of tablets in the drawer. Fadwa creeps up behind him surreptitiously. She watches him from behind the curtain at the window. She checks that he is putting the tablets into his mouth now, then swallowing them with water from the tumbler. She hurries back to the sofa, in front of the TV, before Shadi comes back too.

Now Shadi sits down on the sofa next to her. The father gets up to prepare dinner for them. Fadwa talks to Shadi in amazement. She tells him that today is the third since this uprising broke out, and the President has still not appeared. Shadi presses his lips together and looks as if he is thinking deeply, shakes his head with a knowing air and tells Fadwa that he will appear, he’s just got some things to do that he, Shadi, knows all about, and then he will appear. Fadwa gives him a long, thoughtful look, then goes back to watching the TV.

The father calls Fadwa to help him carry the plates of food from the kitchen to the dining table. Fadwa hurries in to him. She knows very well that in reality he doesn’t need her help except to keep any eye on the atmosphere, to make it easier for him to sneak an extra dose of Shadi’s medicine into his food.

After they have eaten dinner, the three of them sit in front of the TV again. The channel is showing a breaking news item on the titles that run along the bottom of the screen. It says that the President will appear in a speech shortly. Shadi springs up and says, “Didn’t I tell you?” to them several times over.

Neither the father nor Fadwa know that Shadi alone knows where the President has been until this moment. Shadi knows that during the past three days the President has been meeting with Rim’s family, he’s been beseeching them to give him his job back, to return the situation back to how it was before and send the people back to their dens.

When the President makes his speech, in which he seems unconcerned about what he is saying, Shadi asserts that Rim’s family has almost succeeded or has actually succeeded in doing it. After the speech, Shadi informs his father and Fadwa knowingly that things will return to normal within the next two days at most.

When the riots, which break out immediately after the speech, begin, the father decides that Fadwa will not go to work the next day. She objects and yells at her father, trying to persuade him that her work is not just a job but is a mission that it is her duty to perform. Shadi, who has slept through the two of them yelling, wakes up. He knows the reason for their quarrel and he screams hysterically into Fadwa’s face. He calls her filthy names. He threatens her, saying “You daughter of a whore, you fucking bitch, you’re not going out or I’ll beat the crap out of you!” Fadwa looks at her father, who is standing there in silence, then tells them both that she will not go out. Shadi asks her to pass him her handbag. So she passes it to him obediently then tells them that she is heading off to bed.

Lying on her bed, Fadwa cries bitterly. It would be possible for her to go out despite their wishes, but she will not do it, not from fear of Shadi, but from fear for him.

Fadwa sees her work as a presenter on BBC Arabic as an important revolutionary mission. It is no less important than what the demonstrators are doing now in Tahrir Square. She sees herself as conveying the truth. She is conveying their voice to the whole world. To tell the truth, she would dearly love to be with the demonstrators now, but she will not do it. She is afraid, not of getting killed in the demonstrations, but of the fear and the anxiety it would inflict on her father and brother.

On the Saturday following the Friday of Rage Fadwa stands at night on the balcony with Shadi. They hear the sound of fighting in the street, followed by firing and women screaming. Shadi is terrified and drags Fadwa inside by her arm. Fadwa cries, she avoids looking into Shadi’s eyes. Against her will, their glances meet and she sees in his eyes the terror that she was afraid of seeing. She will not forgive. That is what she decides at this moment. She will not forgive the President and his regime that have caused her to see such a look in her brother’s eyes, even if the people and the families of the martyrs forgive them for shedding the blood of their sons. She is crying at this moment not from fear of the state of terror and the insecurity, for she has known ever since she saw yesterday’s speech that the President is definitely making people choose between safety with him or chaos without him. But she is crying from fear for Shadi.

Somebody knocks at the door of the flat and their father runs to open it. Karim, the neighbours’ son, is asking the father to come out with them to protect the building from what the thugs are doing. The father closes the door and goes to change his clothes, but Shadi stops him and says that he will go down himself. The father quickly gives in to his wish because in his condition he cannot withstand any fighting. Shadi does indeed go down, after picking up a club to carry with him. Fadwa wants to go with him, she doesn’t know what sort of panic attack he might suffer out there all by himself. Shadi knows what is going on in his sister’s head, so he locks the door behind him with the key. He comes up about every half an hour and asks Fadwa to make him a cup of tea, then goes back down again.

The call to dawn prayers comes. Fadwa feels compassion for her father, who has fallen asleep on the sofa in the living room. She wakes him up so that he can pray, and asks him to go bed afterwards. She tells him that she will not go to bed until Shadi comes back up and she is sure that he is asleep.

At nine a.m. Shadi finally decides that he will not go back down again. He talks to Fadwa about the events of the horrific night. He says that Rim’s family have given the President the job of terrorising the people. He says that they are making use of devils and demons to assist him with that. He says that he himself saw two yellow-coloured devils in an ambulance down there. Fadwa observes that he is trembling violently as he talks. She tries to calm him and asks him to go to bed.

Fadwa watches the TV for about an hour after Shadi has gone to bed. She tiptoes into his room, and tries to check in the dim light that he is finally asleep. She is unable to see his eyes but she can hear his regular breathing, or that is how it seems to her. She leaves his room. She gets dressed. She fetches her handbag from the kitchen cupboard. She opens the door of the flat and slips out quietly, heading for work.

Fadwa doesn’t know that Shadi was not asleep. He is now trembling on his bed. He feels intense fear and he sobs. He heard all Fadwa’s movements outside and he knew she was determined to go out but he was incapable of moving to prevent her. Fear has completely paralysed his limbs.

Fadwa returns home two days later, at midday on Tuesday. (The father) welcomes her without any reproach. He just tells her, appearing on the verge of collapse, that Shadi is in a very bad state and is not sleeping. She tries to appear strong as she tells her father that he must take him to the doctor tomorrow without his knowledge. She suggests that her father should pretend to be ill while she is at work and should ask Shadi to take him to the heart specialist.

Fadwa goes in to Shadi’s office. She finds him sitting with his eyes wide open, clutching a copy of the Qur’an and reading it aloud, repeating verses like a shaykh exorcising a devil. He is trembling incessantly, his lips are blue and the muscles on the left side of his jaw are twitching erratically, involuntarily. She hugs him and he stands there, unable to believe that she is still in the land of the living. He asks her about the rest of the hostages. She informs him that they are fine, and that everything is fine, God willing.

Fadwa doesn’t know that the latest events reminded Shadi of that terrorist incident that he was involved in two years ago. When he was sitting with Rim at sunset on one of the marble seats at the university, everyone around them suddenly fled in a panic. Everyone was screaming and running while Shadi and Rim sat in their place not understanding what was going on or knowing the reason for it. Within minutes the university and its campus was completely empty except for them. Rim felt afraid. Shadi reassured her and he got up to cautiously check the empty campus around them. Shadi saw an indistinct yellow glow that darted past quickly and disappeared, with a hissing sound, behind the trunks of the enormous ancient trees. Sometimes it approached Shadi and at others it moved away. Shadi knew that it was the devil, so he returned quickly to where Rim was sitting, hugged her, closed his eyes and started reciting verses that he remembered from the Qur’an. Until Allah finally saved them.

At that moment the President sent a battalion of the Republican Guard to save Rim and Shadi. The incident was written about in the newspapers the following day, but they did not mention that the Presidential Guard had intervened to exterminate the devil, but said it was to pursue a dragon which had escaped from the zoo and was attacking students on the university campus.

After that, the way Rim treated Shadi would change and their relationship crumbled away. Shadi would follow her surreptitiously to discover the reason, and the day came when he discovered the whole truth. Rim’s family were evil sorcerers. They worshipped the devil, who had chosen their beautiful daughter Rim for himself. And thus the family became bound up with him in a blind allegiance. They used black magic to split Shadi and Rim up, and Rim was the one most affected, bearing in mind that she was living in their den, so she fell totally under their control.

Shadi also knew that the President’s intervention was thus not for the sake of Allah. The President was afraid that Shadi would destroy the devil and burn him. The President made use of Rim’s family in the Country’s Affairs Department. The President could not rule without the assistance of the devil and using black magic against his whole people.

Once Shadi knew all that, he tried to expose it all. The President would unleash one of the dogs of State Security on him, to rape him in the university toilets. After that, Rim’s family would threaten him with raping his sister and setting fire to his father. Only then would Shadi back down and decide to forget about Rim and give her up forever.

On the Wednesday night, the President delivers his second speech. Afterwards, Shadi comments that they must not trust him or sympathise with him. He asks Fadwa to contact her friends in the square and ask them to return to their homes immediately. Shadi is convinced that the President will gather the greatest number of people possible together and will seize them in order to offer them as a sacrifice to the devil. There is indeed a large number of hostages with him now, and the people should all stay in their homes so that Shadi himself can find a means to save them. Fadwa, who notices her father surreptitiously wiping tears from his eyes, indulges him.

On the morning of the following day, Shadi has not slept, as is normal for him these days, he is crying hard, and begs Fadwa not to leave the house. He kneels down to kiss her feet. Fadwa sits on a chair in the living room and tells him that she will not go out, in compliance with his wishes. She takes advantage of his going to the bathroom and leaves quickly and closes the door behind her.

After midday, the events of The Battle of the Camels begin. Fadwa follows them from her workplace and she receives calls and pleas for help from the square. She moves around, she comes and goes, and through all that tears keep pouring down her face until in time she forgets that she is crying.

At sunset, she replies to her father who has called her on her mobile. She hears him start to cry, she takes a breath and says “Have you seen, Dad, what have the heathen sons of dogs done?!… Never mind, Dad, the blood of those people will not be wasted.” Her father’s voice on the other end is chopped. He tells her that he is crying for the sake of her brother who ran away from him when he was trying to take him to the doctor in accordance with the plan that he had agreed with her. Her father tells her that her brother is now missing altogether, he does not have an ID card on him nor a mobile, not even any small change in his pocket. Her father begs her for help, saying that he doesn’t know what he should do. Fadwa takes her handbag and leaves Maspero [the headquarters of the Egyptian Radio and Television Union] in a hurry without even asking permission. She gets in her car and drives around the streets searching for Shadi. She calls her father – who is also out searching – from time to time.

She drives around the main roads and narrow side-streets of Ayn Shams where Rim, his ex-girlfriend, lives. At three in the morning she is driving her car along Rameses Street when a friend of hers calls to tell her about a sniper and countless numbers of deaths and injuries. Fadwa gets out close to the Ghamra metro station and sits on the pavement. She slaps her face several times. Fadwa smacks herself and screams, her tears mingle with her snot in the pitch-dark of the completely empty street. Her mobile rings again. Her father asks her to come back home and tells her that Shadi is now with him and that they are on their way to the hospital.

Fadwa will learn from her father when he returns that the army contacted him to ask him if he knew anyone called Shadi and requested that he head for the airport immediately to take him back. When Shadi arrives, the father finds him barefoot. His clothes are ripped and he has multiple wounds. He will learn from the captain that he was beaten up by people in the Sheraton compound who thought that he was tripping and the army only managed to rescue him from their hands by the skin of their teeth, realising belatedly that he was not fully in his right mind, and were able by some miracle to find out his name and the mobile number that they called him on.

The father gets in the car after helping the exhausted Shadi to stretch out on the back seat. The captain, speaking only to him, says, “Take good care of him, Hajj, it would be a shame to let someone in that state out on his own in these troubled times.” The father wipes away a tear that he can’t fight back and takes Shadi to the hospital.

Neither the father nor Fadwa know that Shadi fled from his father in the morning in order to rescue Fadwa who had been detained with the hostages when she went out that morning. The hostages were all together in the Al-Fateh mosque and the President’s men kept smuggling them from mosque to mosque to prevent Shadi, their saviour, from arriving to rescue them. They finally came to a stop in a mosque in the Sheraton compound and Shadi managed to trick his way into it before it was evacuated at the time of evening prayer. The hostages were praying at the time, pleading with Allah to rescue them from the situation they were in. Shadi interrupted their prayers and freed them all.

He punched some of them, but that didn’t matter because it was all for their benefit at the end of the day. When Shadi was sure they had all left the mosque and were safe, he finally left the mosque himself and was met outside by the dogs of State Security wearing plain clothes. They showered blows down on him, then handed him over to the Republican Guard who in their turn gave him a good beating. When Rim learnt from her family what was happening to him, she asked the devil to call his soldiers off him and threatened that otherwise she would desert him. The devil acquiesced to her command, and requested that the President let Shadi go, so the President immediately gave an order to the Republican Guard to phone his father so that he could come and take charge of him.

A week later, on the Thursday, Fadwa would receive leaked information, in the course of her work, of a report that the President had stepped down that night. She hurriedly finishes her work and decides to go home to listen to the speech with her father so that they can share in the joy together.

At twenty minutes to ten at night, she is downloading a set of the most famous patriotic songs onto her computer at home. She connects a speaker to the computer, and decides that the celebration will be loud and last until dawn.

After the speech Fadwa was trying to stand up, but she just couldn’t. She thought of calling out for her father, then gave up the idea, out of pity for his state of health. She told herself that that was the last thing he needed. She kept quiet, and after several minutes she tried again to stand up, but she still couldn’t do it. She burst into silent tears, after which she fell asleep where she was, sitting on the chair. She felt her father waking her up and leading her to her bed. She wanted to know what the time was but she could not see the clock, she was just focused on the fact that she was actually walking now with her father.

The following day she sees a brilliant video on the computer telling the story of the events of the revolution from the very beginning. She feels deeply moved and tears run down her face. She prays “Oh, Lord, we did what we had to do, now you must play your part, oh Lord.” Her father is sitting in the living room watching terrestrial TV, when she hears a collective roar from the street and the neighbours, like the one you hear when the national team scores a goal in an African Nations Cup match. She runs out to the living room and finds her father prostrate, crying, on the floor. She follows with unbelieving eyes the breaking news titles on the TV reporting the news of the resignation. She starts to jump up and down like a crazy woman. She is yelling, believing that she is trilling cries of joy, but she doesn’t know how to do that so she just keeps on yelling. Her father watches her, sitting on the floor, and laughs amid his tears.

She prances back to the computer and starts playing the patriotic songs that she downloaded yesterday at top volume. She dances, she jumps and carries on shouting, her father comes into her room, smiling at her, dancing with her, then hugs her and cries.

The following day, in the afternoon, when Fadwa has finished getting dressed, she goes out, accompanied by her father, to bring Shadi back from the hospital, where he has spent ten days receiving intensive treatment. Shadi is calm now. His face is bloated from so much sleep and he has almost zero ability to concentrate because of the high dosage of strong medication that he has been on there.

Once home, Shadi sits in front of the TV. He watches for himself the resignation speech, which all the channels are broadcasting on continuous repeat. Fadwa sits at his side. He laughs and points at the man10 standing behind Omar Suleiman and says to Fadwa “Why is that man there doing that?” Fadwa notices for the first time the man with his scowling face and suspicious penetrating glances, and she laughs too.

Shadi asks her about dinner and she tells him that they will get a Kentucky Fried Chicken takeaway tonight. He asks her to order the 68-piece meal for him and she laughs and tells him that she’s ordered the 116-piece one for him, then he laughs too.

After a few minutes they watch the speech which is being shown again. Shadi looks contemplatively at Omar Suleiman then turns to Fadwa saying “Can you believe it? – that Suleiman was using black magic too?” Fadwa looks aghast and the delight drains from her face, indeed her right eye flickers in a nervous movement that she can’t control. Shadi observes her reaction and bursts out laughing and says, “I’m kidding you, you idiot.” She smiles slowly and cautiously, and his giggles grow louder and he repeats it to her, struggling to breathe from his laughter, “I swear to God, and even on the life of our father.” She contemplates his non-stop laughter, then she laughs too, until tears fill her eyes, and the sound of their intermingled laughter fills the space of the living room.

Eman Abdelrahim is an Egyptian short-story writer best known for her collection Rooms and Other Stories. One of her stories appears in The Book of Cairo, published by Comma Press

An extract of Laugh and the World Laughs with Me was first published in the summer 2019 issue of Index on Censorship.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”How governments use power to undermine justice and freedom” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2019%2F06%2Fmagazine-judged-how-governments-use-power-to-undermine-justice-and-freedom%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The summer 2019 Index on Censorship magazine looks at the narrowing gap between a nation’s leader and its judges and lawyers.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_single_image image=”107686″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2019/06/magazine-judged-how-governments-use-power-to-undermine-justice-and-freedom/”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

7 Aug 2018 | Magazine, News and features, Volume 47.02 Summer 2018 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_video link=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5Rswx2Z7SDw&list=PLBi_wVTZlqjxOK7M028WJ5efw3oslTy4T”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

What does paradise mean to you? A pina colada on a white-sand beach? A beautiful sunset over Mayan ruins? The summer 2018 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at some of the world’s most popular “paradise” destinations and asks whether their reality quite lives up to their reputation (hint, it doesn’t, especially when it comes to free expression). But criticise these places all you like, the concept of paradise at least, whether lost or found, has been quite the inspiration for a lot of iconic music. Here we pick our top tracks in tribute to the theme. We hope you enjoy listening, sort of.

Holiday by Madonna

Ah Holiday by Madonna, that quintessential going away hit, especially when it first came out in the 80s. This song is pretty syrupy, we’re not going to lie. Madonna calls for everybody to “put [their] trouble down” for a day and celebrate. There’s not really a hint that holiday doesn’t always equal everything being great. But what if you’re a tourist in Baja Mexico Sur, where you might very well see bodies of those involved in the drug trade dangling from bridges, as Stephen Woodman explores in the magazine? Not such a holiday then is it Madge?

Holidays in the Sun by the Sex Pistols

The Sex Pistols actually have experienced a holiday gone wrong, when they went to the island of Jersey and were kicked out. So they switched the sunshine for several weeks in Berlin instead. And this inspired their song Holidays in the Sun, in which they want you to “see some history” and visit “the new Belsen”. It’s basically a really catchy way of arguing for visiting grittier places.

Paradise by Coldplay

Coldplay’s song Paradise is about dreams dashed, in this case that of a girl who grows up in a world that is far from paradise and can only access it through her dreams. It reminds us of the superb short story by contributing editor Kaya Genç, who writes about an elderly man in Turkey who looks back on his life, his expectations for paradise and what became of them.

Cruel Summer by Bananarama

Admittedly this is less about a destination gone bad and more about not being able to go to said destination. There are lines like “My friends are away and I’m on my own.” Summer is cruel because summer is about staying put. But maybe that’s for the best? What’s so great about going to a destination that is tumbling down a free speech index? Just some food for thought Bananarama.

Bad Moon Rising by Creedence Clearwater Revival

At the song’s centre is the moon. The moon! Who hasn’t stared at the starry sky when abroad as a holiday highlight? And yet… it’s a bad moon. The lyrics are nothing short of foreboding; “I see trouble on the way” for example. Despite the downbeat lyrics, the melody remains pretty upbeat. Sort of like being a tourist in Sri Lanka, where you’re surrounded by beautiful sites but also the legacy of war.

Holiday by Dizzee Rascal

Talk about making an offer you can’t refuse – Dizzee Rascal invites the object of his affections away on what sounds like the ideal vacation (or two or three – take your pick from the South of France, Ibiza or Milan). There’ll be champagne and a sun tan. Perfect! But why no mention of Malta or the Maldives or those other beautiful hotspots? Maybe Dizzee ran out of line space or maybe Dizzee circa 2009 foresaw the issues that would affect these areas by 2018.

Buffalo Soldier by Bob Marley

Go to a beach bar in the Caribbean, that ultimate holiday destination, and you’d be hard pressed not to hear Bob Marley. For many a visitor he is the soundtrack of the region. And yet as much as his songs are soothing, they are also very political. Marley was a man who would not gloss over the darker sides of paradise. For this reason, we like to think if he was alive today he would have contributed to our issue. Buffalo Soldier, a reminder of the history of slavery in the USA and the Caribbean, is case in point. Easy to enjoy, until you actually listen to the lyrics.

Holiday by Green Day

Our third and final offering with holiday in the title and yet the only one of the three songs that isn’t in total praise of a vacation. Green Day’s tribute to your time off talks less about nice things and instead looks at US political conservatism under George W. Bush and the Iraq war. The chorus’ line – “This is our lives on holiday” – attacks US apathy. Released in 2005 but certainly still relevant to different areas of the world today.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Trouble in Paradise” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2018%2F06%2Ftrouble-in-paradise%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The summer 2018 issue of Index on Censorship magazine takes you on holiday, just a different kind of holiday. From Malta to the Maldives, we explore how freedom of expression is under attack in dream destinations around the world.

With: Martin Rowson, Jon Savage, Jonathan Tel [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”100842″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/06/trouble-in-paradise/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

30 Jan 2018 | News and features, Volume 46.04 Winter 2017, Volume 46.04 Winter 2017 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

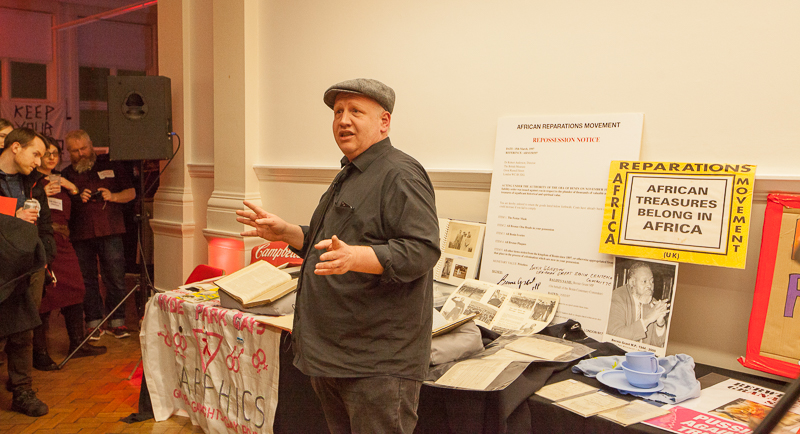

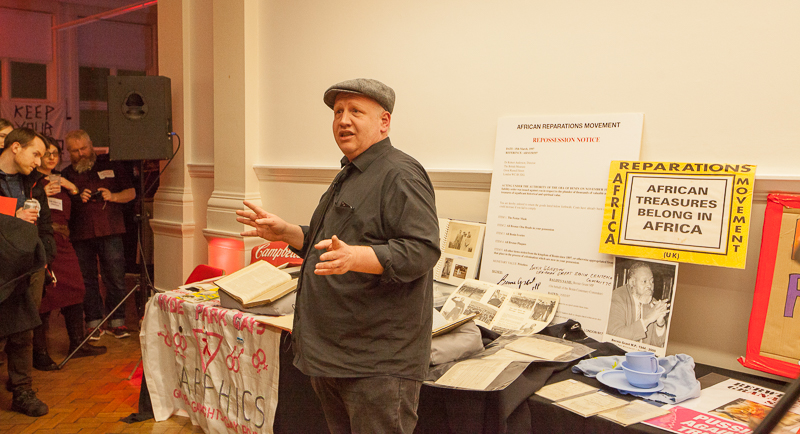

Peter Tatchell discusses the importance of the right to protest. (Photo: Sean Gallagher / Index on Censorship)

Index on Censorship magazine celebrated the launch of its winter 2017 magazine at the Bishopsgate Institute in London with an evening exploring the legacies of iconic protests from 1918 and 1968 to the modern day and reflecting on how today, more than ever, our right to protest is under threat.

Speakers for the evening included human rights campaigner Peter Tatchell, Bishopsgate Institute special collections and archives manager Stefan Dickers and artist Patrick Bullock.

Tatchell discussed the importance of protest for any democracy and the significant anniversaries of protests in 2018 throughout his speech. “This year is a very special year, a very historic year, I think that those protests remind us that protest is vital to democracy,” he said. “It is a litmus test of democracy, it is a litmus of a healthy democracy. Democracies that don’t have protest, there is a problem, in fact, you might even say they aren’t true democracies.”

“With 1968 came the birth of the women’s liberation movement, the mass protests in Czechoslovakia against Russian occupation, and, of course, the huge protests against the American war in Vietnam,” Tatchell added. “Those protests all remind us that protest is vital to democracy.”

Bishopsgate Institute special collections and archives manager Stefan Dickers at the launch of What price protest? (Photo: Sean Gallagher / Index on Censorship)

This year also marks the centenary of the right to vote for women in Britain. Dickers showcased artefacts the Bishopsgate Institute’s collection of protest memorabilia, including sashes worn by the Suffragettes and tea sets women were given upon leaving prison for activities related to their activism.

Suffragette sashes at the launch of What price protest? (Photo: Sean Gallagher / Index on Censorship)

Attendees included actor Simon Callow, who stressed the importance of protest and freedom of expression: in an interview at the event with Index on Censorship. “There are all sorts of things that people find inconvenient and uncomfortable to themselves, that they don’t wish to hear, but that’s not the point,” he said. “The point is that if some people feel very strongly that certain things are wrong, then they must be allowed to say something.”

Disobedient objects at the launch of What price protest? (Photo: Sean Gallagher / Index on Censorship)

Eastenders actress Ann Mitchell, who also attended the event, said: “There is no question in my opinion, that the darkness in the world at the moment must be protested against. All the advantages we have won as women, as ethnic minorities, are being destroyed, they are being wiped out. Unless we hear voices of protests for that, that will continue.”

The night concluded with a performance by protest choir Raised Voices.

Index magazine’s winter issue on the right to protest features articles from Argentina, England, Turkey, the USA and Belarus. Activist Micah White proposes a novel way for protest to remain relevant. Author and journalist Robert McCrum revisits the Prague Spring to ask whether it is still remembered. Award-winning author Ariel Dorfman’s new short story — Shakespeare, Cervantes and spies — has it all. Anuradha Roy writes that tired of being harassed and treated as second-class citizens, Indian women are taking to the streets.b

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”What price protest?”][vc_column_text]Through features, interviews and illustrations, the winter issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at the state of protest today, 50 years after 1968, and exposes how it is currently under threat.

With: Ariel Dorfman, Anuradha Roy, Micah White, Richard Ratcliffe[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”96747″ img_size=”medium”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

18 Dec 2017 | Volume 46.04 Winter 2017, Volume 46.04 Winter 2017 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text][/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The winter issue of Index on Censorship looks at the state of protest 50 years after 1968, the year the world took to the streets.

The podcast includes interviews with Pavel Theiner, who was 11 years old when the tanks rolled into Prague in 1968. Speaking on the state of protest today is Steven Borowiec, a journalist based in South Korea, whose article in the magazine looks at whether the current leader, who came to power on the back of protests, will protect this necessary right. And Sujatro Ghosh, an Indian photographer, discusses his innovative project to highlight the unfair treatment of women in the country.

Also on the podcast is an interview with Floyd Abrams, the lawyer who worked on the Pentagon Papers case. He discusses how the First Amendment has not been under this much attack since World War I.

Print copies of the magazine are available on Amazon, or you can take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions. Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”What price protest?”][vc_column_text]Through features, interviews and illustrations, the winter issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at the state of protest today, 50 years after 1968, and exposes how it is currently under threat.

With: Ariel Dorfman, Anuradha Roy, Micah White, Richard Ratcliffe[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”96747″ img_size=”medium”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]