2 Mar 2017 | Digital Freedom, Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, News and features, Sweden

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

With a well-developed public service TV and Radio sector, press subsidies and political stability, being a journalist in Sweden is a touch easier than many other places around the world. Sweden is also relatively good at protecting journalists, and though they have had their disagreements, the state and political parties are broadly supportive of open, well-funded journalism. As a foreign correspondent, it is also a refreshingly easy country to work in, with people usually willing and ready to talk to the press.

A spectre that has haunted Swedish journalism for decades is anti-democratic extremism, a phenomenon given new impetus by the rise of mainstream nationalist politics in recent years. Journalists have been labelled as “cultural Marxists” and members of the so-called pk-elit, shorthand for the politically correct elite, by members of old white power organisations and the newer alt-right movements alike.

Much of the far-right view Sweden’s generally liberal newspapers and its public broadcasters as part of a shadowy agenda that is failing to report on the real issues, covering up crimes by immigrants and mounting a propaganda campaign against nationalist movements. As well as specific journalists, hatred of the media, in general, is widespread. The result is an ongoing campaign of intimidation and death threats.

Local journalists at Nerikes Allehanda, the local newspaper for the town of Örebro in central Sweden, were recently issued with death threats after reporting on Peter Springare, a local policeman who had posted on social media about immigrants causing crime in the city on 3 February. Springare was hailed as a brave whistleblower, but reporters and the newspaper’s leader writer received a wide range of abuse for discussing both the correctness and ethics of his statements. Shortly before Christmas, journalist Robert Laul received death threats after criticising controversial right-wing journalist Niklas Svensson’s reporting of undocumented migrants.

Similarly, white powder – which turned out to be harmless – was sent to Janne Josefsson, a Swedish investigative journalist based at public broadcaster SVT in Gothenburg last month. Authorities had to evacuate the entire studio building, severely disrupting the work of SVT’s news teams. The package also contained an anonymous death threat. Josefsson and his colleagues at the Uppdrag Granskning investigative show are known for reporting on all aspects of Swedish society, from the far right to organised crime, and are no strangers to intimidation.

The Swedish journalists’ union has documented how attacks on journalists are on the rise. This is troubling for a country that has long cast itself as a refuge for persecuted media workers from Russia, East Africa and elsewhere. In spring 2016 a survey of members of Swedish Radio’s journalistic corps and reporters at the association of newspaper publishers TU found that one in three had been subject to some kind of threat in the previous year.

Although a great number of those threats came from the populist right and more established neo-Nazis, journalists in Sweden have also been harassed by both criminal gangs and radical Islamist groups in recent months. In the town of Gävle north of Stockholm for example, Anna Gullberg from local paper Gefle Dagblad received a death threat in response to the paper’s investigation of a radical mosque, with the perpetrator finally sentenced last week.

These threats are more serious than the torrent of abuse and the attempts to undermine journalistic integrity on Twitter felt by reporters around the world. In Sweden, it is not difficult to find out where people live or locate their social media profiles. As a result, many journalists have been forced to either apply for the removal of their personal details from public databases or move home. A Swedish tradition that places journalists prominently at the heart of an open society with relative respect for difference of opinion is under serious threat.

Lisa Bjurwald, a media commentator, author and part owner of industry news site Medievärlden has warned that “journalists avoid writing about racist political parties and neo-Nazi groups for example because they can’t deal with the storm and volume of hate mail” in a recent newspaper interview.

The underlying questions though are how many of these alleged threats carry any risk, and does it really matter if they do? Journalists in Sweden increasingly feel as if their safety is routinely threatened as part of their work, however genuine the threat may be.

In the sea of online abuse there may only be a handful of real, tangible threats, but knowing what is casual intimidation or egotistical posturing and what is a genuine risk to the safety of journalists and their families is almost impossible. In 2015 Niklas Orrenius, one of Sweden’s leading reporters and the star journalist at newspaper Dagens Nyheter, temporarily left the country with his family after a series of threats connected to his coverage of an anonymous far-right blogger. A well-known racist activist had photographed himself outside the front door to Orrenius’ apartment and uploaded the picture to the web with a promise to come back.

With threats like this, most journalists are understandably unwilling to call the bluff of Sweden’s armchair warriors.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner equal_height=”yes” content_placement=”middle” css=”.vc_custom_1488908025353{margin-top: 25px !important;margin-bottom: 25px !important;background-color: #dd3333 !important;}” el_class=”text_white”][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Defend Media Freedom” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:28|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fdefend-media-freedom-donate-index%2F|||”][vc_column_text]SUPPORT INDEX ON CENSORSHIP

Reporters working to share the truth are being harassed, intimidated and prosecuted – across the globe.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″ css=”.vc_custom_1488908111801{background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/newspapers.jpg?id=50885) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

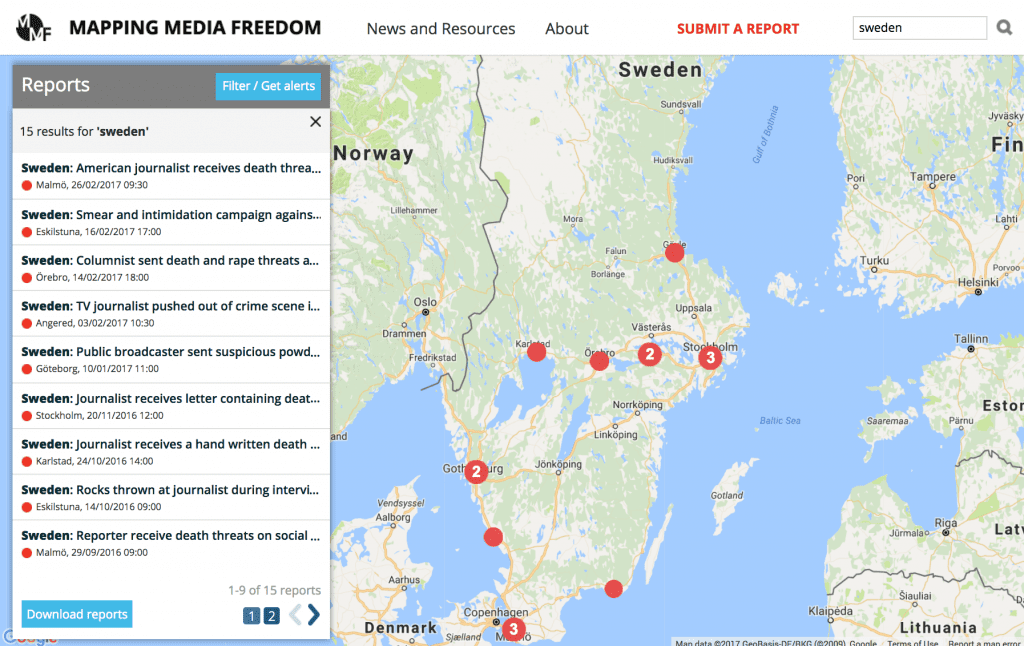

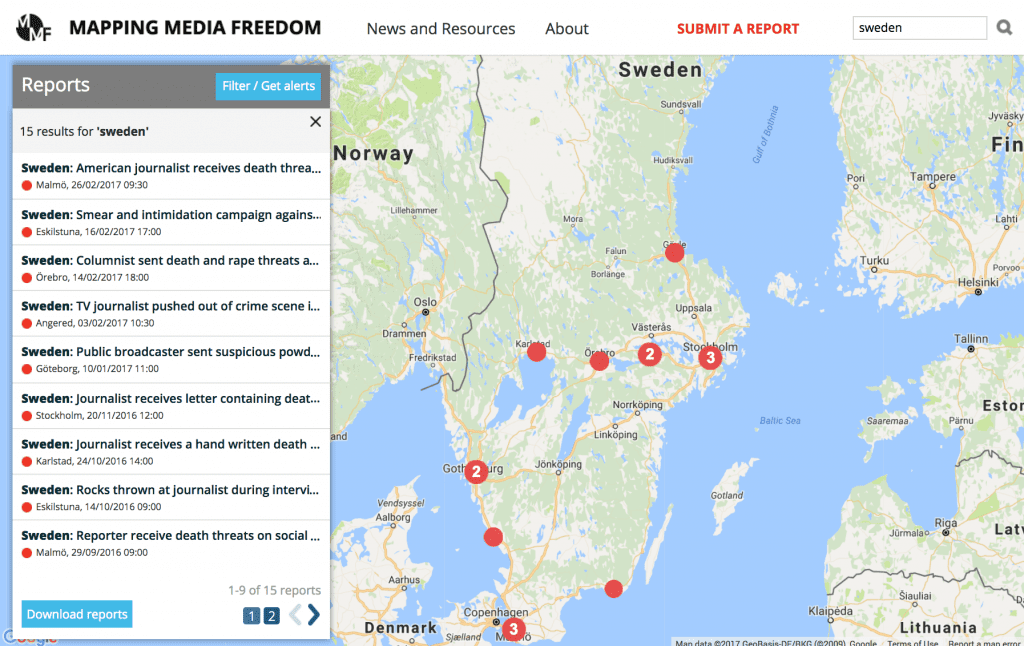

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1488908132919-7c688c97-6409-9″ taxonomies=”9008, 6564″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

28 Feb 2017 | Index Reports, Mapping Media Freedom, Press Releases

Freedom of expression campaign group Index on Censorship launches Media Freedom Month in March with the release of its annual report into media freedom in Europe. The report shows journalists face regular harassment, legal sanctions and even jail for doing their job – even in supposed democracies. Index’s Media Freedom Month aims to raise awareness of and funding for its work campaigning on press freedom.

Freedom of expression campaign group Index on Censorship launches Media Freedom Month in March with the release of its annual report into media freedom in Europe. The report shows journalists face regular harassment, legal sanctions and even jail for doing their job – even in supposed democracies. Index’s Media Freedom Month aims to raise awareness of and funding for its work campaigning on press freedom.

“Right now, journalists and journalism are threatened from all directions: UK journalists who travel to the US are being told they need to hand over their mobile phone contacts and Facebook passwords. US journalists are being labelled as peddlers of ‘fake news’ over any articles the President dislikes and reporters across Europe face a host of laws that hamper their ability to work,” said Index chief executive Jodie Ginsberg.

Media Freedom Month will begin with the launch on Tuesday of the latest Mapping Media Freedom report on Europe and will end with an exclusive study of media freedom in the United States that goes well beyond the current focus on Donald Trump and his relationship with the press.

“A country without a free media is not a free country: Journalism provides a vital check on corruption and abuse of power and we must fight to protect it,” said Ginsberg.

Between 1 January and 31 December 2016, Mapping Media Freedom’s network of correspondents, partners and other journalists submitted a total of 1,387 verified threats to press freedom in 42 European countries.

“The precarious state of press freedom across the globe is underlined by the volume of verified incidents added to Mapping Media Freedom in 2016. The spectrum of threats is growing, the pressure on journalists increasing and the public right to transparent information is under assault. People who are simply trying to do their job are being targeted like never before. These trends do not bode well for 2017,” Hannah Machlin, Mapping Media Freedom project officer, said.

Some of the major themes in the data – and which journalists should be wary of in 2017 – include:

- Violence from right-wing groups

- Dangers faced when reporting on protests and demonstrations organised across the political spectrum

- Impunity: Physical attacks on journalists not properly investigated; government officials intimidating reporters without fear of punishment

- Difficulties reporting on refugees, including being denied access and violence

- Silencing journalists by arresting them on ties to terrorist or extremist groups

- Criminalised libel laws subjecting media outlets to high fines

- Economic difficulties leading to the closure or restructuring media outlets and buyouts by wealthy businesspeople, often leading to job cuts and dismissals

- State of emergency laws being used to detain journalists without charge

- Death threats and smear campaigns disseminated online

The 2016 report is available in web and pdf format at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/plus/

For more information, please contact Hannah Machlin, Mapping Media Freedom project officer at [email protected]

About Mapping Media Freedom

Mapping Media Freedom – a major Index on Censorship project and a joint undertaking with the European Federation of Journalists and Reporters Without Borders, partially funded by the European Commission – covers 42 countries, including all EU member states, plus Bosnia, Iceland, Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro, Norway, Serbia, Turkey, Albania along with Ukraine, Belarus and Russia in (added in April 2015), and Azerbaijan (added in February 2016). The platform was launched in May 2014 and has recorded over 2,700 incidents threatening media freedom.

About Index on Censorship

Index on Censorship is a freedom of expression charity that campaigns against censorship and promotes free expression worldwide. Founded in 1972, Index has published some of the world’s leading writers and artists in its award-winning quarterly magazine, including Nadine Gordimer, Mario Vargas Llosa, Samuel Beckett and Kurt Vonnegut. It also has published some of the greatest campaigning writers from Vaclav Havel to Elif Shafak.

27 Feb 2017 | Mapping Media Freedom, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Each week, Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project verifies threats, violations and limitations faced by the media throughout the European Union and neighbouring countries. Here are recent reports that give us cause for concern.

Independent journalist Elchin Ismayilli, who used to contribute to Cumhuriyet newspaper and Azerbaijani Saadi, was detained on 17 February on charges of extortion through intimidation and abuse of power, reported Azadliq Radio.

According to the journalist’s lawyer, Ismayilli is being charged for threatening an employee of the local culture and tourism department.

The journalist says the allegations are not true.

A month before, Ismayilli asked to borrow 1000AZN from the person who is allegedly accusing him of extortion. He was detained when picking up the money.

During a meeting with his lawyer, he explained he had known this individual since 2003 and that they had good relations.

In September he received a warning from the police on was called into questioning for allegedly assaulting an officer.

The journalist ties both incidents to his work.

The French police prevented freelance journalist Alexis Kraland from accessing a demonstration in Place de la République, in Paris, on 18 February, the journalist reported on Twitter and confirmed to Mapping Media Freedom.

Kraland was intending to cover a protest in solidarity with a young man called Theo, who was allegedly raped during a violent police arrest.

The police asked the journalist for his press card which is not necessary to cover a demonstration as a journalist, Kraland told Mapping Media Freedom.

The Federal Migration Service won its case against Demyan Kudryavtsev, owner of Independent Media, on 21 February, Vedomosti reported.

“It has been established that false data was deliberately submitted in this citizenship application. The Supreme Court acknowledged this”, the court’s press service stated.

FMS did not receive all the necessary data in the application submitted in 2009, Kudryavtsev told Novaya Gazeta.

The President or FMS is now able to deprive him of his citizenship based on the court decision.

New amendments to a 2014 law by the State Duma prohibit foreigners from establishing and owning more than 20 per cent of any Russian media outlet. If Kudryavtsev is deprived of his Russian citizenship, he will not be able to continue owning Vedomosti and other outlets under the Independent Media umbrella.

Hannah Machlin, project officer of the Mapping Media Freedom project, said: “The decision to take away Kudrayastev’s passport will affect the legality of his ownership of media outlets Vedmosti and the Moscow Times, making it a clear violation to press freedom”.

Özgür Gelecek daily’s Newsroom Editor Aslı Ceren Aslan was arrested on 21 February in Şanlıurfa province, Cumhuriyet newspaper reported.

Aslan, who was detained on 18 February, was allegedly subjected to physical violence and strip searched twice during her detention and arrest. Özgür Gelecek reported that Aslan was in Şanlıurfa to report on the recent developments in Syria at the time of her detention.

According to reports, the journalist was arrested on charges of “belonging to a terrorist organisation” and “violating Turkish borders.”

Her arrest brings the number of journalists in Turkish prisons to 154.

Boris Pejovic, a photographer for daily newspaper Vijesti, was insulted and pushed during a brawl on 15 February between MPs from the ruling Democratic Party of Socialists and the opposition Democratic Front in the Parliament of Montenegro, daily newspaper Vijesti reported.

As Vijesti reported, MPs and Parliament security pushed and insulted Pejovic.

Opposition leaders and supporters protested in front of Montenegro’s parliament after the ruling majority stripped two MPs of their immunity from prosecution over their alleged involvement in a coup attempt, Balkan Insight reported.

The incident was strongly condemned by the Trade Union of Media of Montenegro (SMCG).[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

24 Feb 2017 | Croatia, Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, Montenegro, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Independent journalist Jovo Martinovic’s arrest with 13 other individuals during a joint Croatian and Montenegrin police operation on 22 October 2015 began an ongoing ordeal.

Martinovic was taken into custody “on reasonable suspicion that he committed criminal offence – creation of criminal organisation and unauthorised production, possession and distribution of narcotics”, according to Montenegro’s ministry of justice. Media reports explained the case more colloquially: Martinovic was detained for allegedly facilitating a meeting between drug dealers and buyers, and helping them to install a messaging app on their smartphones that is allegedly untraceable by the police.

Following Martinovic’s arrest, it took more than five months for the Special Prosecutor’s Office to raise an indictment against him. Then he spent an extra six months in pre-trial detention before the court case began on 27 October 2016. In total, Martinovic, who insists he is not guilty and the contacts with the suspects spent around one year in jail before the trial even took place. He was conditionally released on 4 January 2017. He remains under a travel ban and must report to police twice a month until the court’s final verdict is issued.

The length of Martinovic’s pre-trial detention provoked OSCE representative on freedom of the media Dunja Mijatovic and other watchdog organisations to call for a swift conclusion of his case. “Prolonged detention can have a detrimental impact on media freedom and a chilling effect on investigative journalism,” Mijatovic said.

The Committee to Protect Journalists, Human Rights Watch and Reporters Without Borders wrote a joint letter to Montenegrin prime minister Milo Djukanovic protesting the prolonged pre-trial detention and prosecution. The International Federation of Journalists wrote a letter to Djukanovic stating that they were “shocked by the gravity of his possible sentence being more than 10 years in prison”. Journalists who have worked with Martinovic wrote testimonies that in support of his professional integrity.

Martinovic has insisted that he is not guilty, adding that his contact with the two of the 13 suspects was linked to his journalistic work.

The main suspects, Dusko Martinovic (no relation) and Namik Selmanovic, who is co-operating with prosecutors, were helping the journalist in his reseatch for two documentaries, firstly a Vice documentary on the infamous Pink Panthers, a gang of gem thieves, and La Route de la Kalashnikov, a documentary about weapons smuggling commissioned by French production company CAPA Presse. The second programme, which exposed illegal smuggling of weapons from the Balkans into western Europe, was aired on the French television channel Canal+.

During one of the court sessions, Dusko Martinovic testified that met Martinovic for the first time in 2012 while he was serving time in prison for crimes related to his membership in the Pink Panthers. He also testified that the journalist had no involvement in illegal activities.

“Jovo did not take part in any drug smuggling operation,” Dusko Martinovic said in the court, Montenegrin daily Vijesti reported. In its coverage, the newspaper reported that Dusko Martinovic stressed that his contacts with Martinovic were strictly connected with the VICE documentary and later for a possible Hollywood movie about the Pink Panthers. Dusko Martinovic also said that he was offered a plea bargain by prosecutors if he testified “that Jovo was included in the drug smuggling”.

The one-year detention of Martinovic has raised questions about the country’s commitment to freedom of the press, Human Rights Watch associate director for program Fred Abrahams wrote: “The start of his trial last week did nothing to allay those concerns. To date, the evidence against Martinovic offered by deputy special prosecutor Mira Samardzic is weak, at best. She has allegedly incriminating statements from two of Martinovic’s co-accused, both of whom face jail sentences and have an incentive to co-operate with prosecutors. She also has recorded phone conversations between Martinovic and the alleged gang leader, Dusko Martinovic (no relation), but defence lawyers and others who have read the transcripts say they contain nothing to incriminate Jovo.”

Once free, it was much easier for Martinovic to tell his side of the story. Speaking to Mapping Media Freedom in a limited capacity about the ongoing case he said: “I do reject with indignation the charges laid against me. I was doing my job as a reporter and that is an undeniable fact.”

Martinovic said that until the trial ends he won’t be giving other statements.

“I will fight in court to the utmost to defend my innocence”.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1490287936930-99f1d6d4-195c-1″ taxonomies=”256, 4612″][/vc_column][/vc_row]