17 Nov 2016 | Mapping Media Freedom, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Each week, Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project verifies threats, violations and limitations faced by the media throughout the European Union and neighbouring countries. Here are five recent reports that give us cause for concern.

After passing a law issued by the interior ministry, Turkey has shut down and arrested members of approximately 370 independent organisations, including many media platforms.

A full list of these organisations is unavailable since the Turkish government claims some cases are still under investigation.

Since the state of emergency declared by Turkey this summer after the attempted military coup, the government has been shutting down media and civil organisations. Some of the organisations recently shut down have been the Dokuz8 News Site, Free Women’s Congress, the Kurdish Writers’ Association and the Fair Women’s Association.

Turkey has declared that all these independent organisations are allegedly linked to terror groups.

One organisation to fall victim to Turkey’s crackdown was the Cumhuriyet Foundation, a secular, liberal media platform. Nine journalists for Cumhuriyet, as well as the president of the executive board, Akın Atalay, were arrested within the past several weeks. They were charged with terrorism, the government saying that although the journalists were not official members of the terrorist group they engaged in activities for the organisation.

The arrest of the Cumhuriyet journalists raises the number of jailed journalists to 144.

Les Jours journalist, Olivier Bertrand, was working in Gaziantep to collect stories about post-coup Turkey. While there, Bertrand was detained by police with no reason given. On Sunday, French Foreign Minister Jean-Marc Ayrault demanded that Bertrand be set free.

Bertrand was released by Turkish authorities and deported back to France.

Freelance journalists Kastus Zhukouski and Aleksei Atroshchanka were working for Belsat TV in Svetlahorsk. While attempting to film trees being cut down by authorities, the two journalists were approached by police, who demanded to see their credentials.

After their IDs were initially checked, a police major who identified himself as Vyazhevich, approached and demanded to see the journalists’ credentials.

Zhukouski and Atroshchanka told the major that they had just shown their IDs and saw no reason so show them again.

Zhukouski told Belsat.eu that, the “major began to shake– his reaction was strange. He began to yell at us, asking if we have accreditation? We said that the right to freely spread information is guaranteed by the Constitution of Belarus. Major said we had to go to the police station. We did not resist. In the station he behaved inappropriately: grabbed the camera, my arm, pushed me, insulted me, and tried to provoke me in every way. I wrote a complaint about such actions of the police…”

After being held in the police station for three hours and having their belongings searched, the journalists were released.

Dennis Schouten, a journalist for PowNed was assaulted at a Rotterdam protest against the children’s character, Black Pete, who is part of the yearly celebration of Saint Nicholas. The character is supposed to be Saint Nicholas’ servant and is usually portrayed by a white person in blackface. The protesters were arguing the portrayal is racist.

While interviewing a protester, Schouten was pushed in front of a moving car. The reporter received no injuries.

The perpetrator was arrested by police at the scene.

Novaya Gazeta correspondent Dmitry Rebrov and a film crew for TV Rain were detained while covering truck driver protests in Moscow.

The demonstrators were protesting the “Plato” system, which charges the drivers tolls on federal highways.

Police detained the journalists when arresting the protesters. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

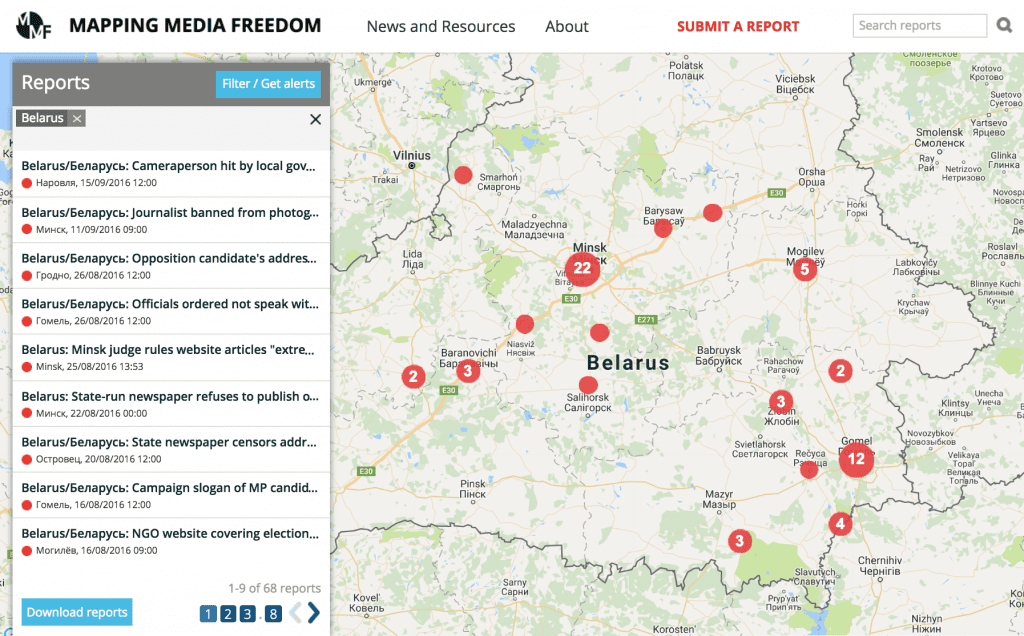

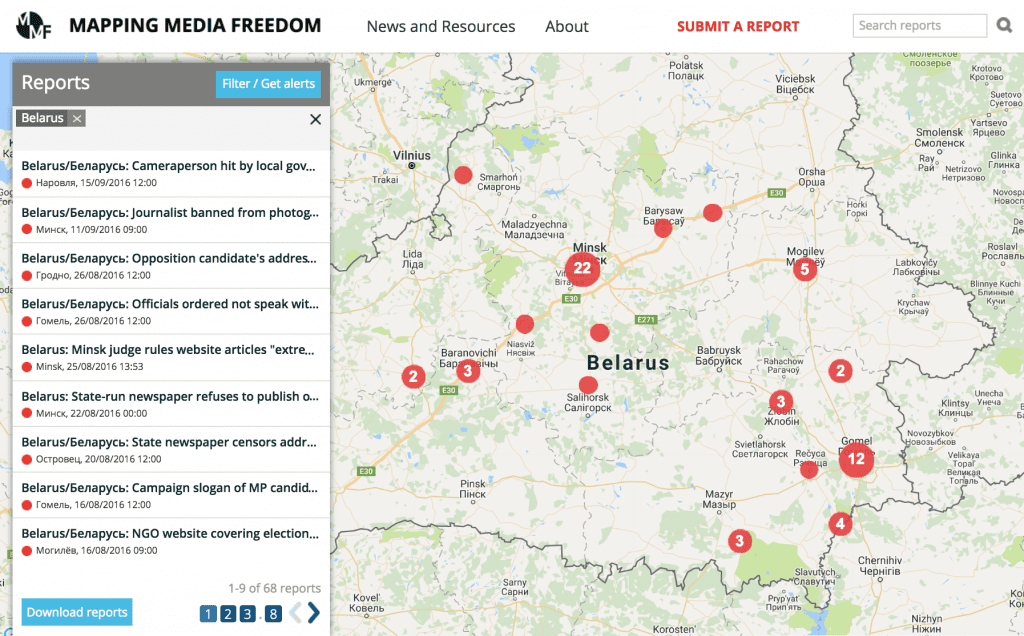

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1479460802604-326201e9-0959-9″ taxonomies=”6564″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

11 Nov 2016 | Mapping Media Freedom, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] Each week, Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project verifies threats, violations and limitations faced by the media throughout the European Union and neighbouring countries. Here are five recent reports that give us cause for concern.

Each week, Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project verifies threats, violations and limitations faced by the media throughout the European Union and neighbouring countries. Here are five recent reports that give us cause for concern.

Turkey’s main internet regulator, Information and Communication Technologies, sent instructions to operators to close VPN services, according to technology news site Webtekno.

The ICT said it was acting within the scope of Article 6, paragraph 2 of law no 5651 in adopting a decision requesting Turkish operators to shut down VPN services.

The decision covers popular encryption services as Tor Project, VPN Master, Hotspot Shield VPN, Psiphon, Zenmate VPN, TunnelBear, Zero VPN, VyprVPN, Private Internet Access VPN, Espress VPN, IPVanish VPN.

According to Webtekno some VPN services are still available such as Open VPN.

“This is clearly detrimental to journalists and the protection of their sources,” Hannah Machlin, project officer for Mapping Media Freedom, said.

Turkey’s internet censorship did not stop with VPNs as the country faced a shutdown of the popular social media sites Facebook, YouTube, Twitter and more. This was the first time in recent years that the Turkish government targeted popular messaging apps such as WhatsApp, Skype and Instagram, according to Turkey Blocks.

The Independent states that it’s unclear whether the social media outage came from an intentional ban, an accident or a cyber attack. Turkey Blocks believes the outage was related to the arrest of political activists for the opposition party the previous night.

Turkey has increasingly utilised internet restrictions to limit media coverage in times of political unrest.

Spanish group Morera and Vallejo, has decided to slash contracts with photographers working for their newspaper, El Correo de Andalucía, according to the Sevilla Press Association (APS).

The three photographers working as “fake” freelancers for the newspaper were on a permanent contract without the benefits of being an employee. New contracts for the photographers worsened their conditions, lowering their pay and lessening the work photographers can put in daily.

APS additionally states that journalists working for El Correo de Andalucía are expected to act as photographers as well, doubling the amount of work they must put in. The newspaper pushed for the merging journalism and photography but journalists are unwilling to steal their coworkers’ jobs.

Four journalists from the Center for Investigative Reporting in Serbia (CINS) have noted that they have been followed and photographed on mobile phones by unknown individuals, NUNs Press reported.

CINS, which is known for reporting on corruption and organised crime in Serbia, believes the stalkers are an attempt to intimidate their journalists. Editor-in-chief Dino Jahic stated that they’re unsure who is behind the harassment, “We are working on dozens of investigations all the time, and each of them could trigger somebody’s anger.”

On its website, CINS wrote that they were determined to continue their investigations despite the intimidation. Their case has been reported to the Ministry of Interior and the public prosecutor’s office in Belgrade.

The online investigative news site Ukrayinska Pravda has reported that Ukrainian authorities wiretapped the outlet’s offices during the summer of 2015.

Editor-in-chief Sevgil Musayeva-Borovyk said in March of 2016, an unidentified person handed in an envelope with operational reports, activities and topics recently discussed by UP. The site has no evidence that wiretapping has continued since then.

According to Ukrayinska Pravda, the security service of Ukraine was carrying out orders from the president’s administration. Ukrayinska Pravda reported that it was not only its journalists that were targeted, claiming the staff of several other media sites have been tapped. Mapping Media Freedom does not yet know which other organisations.

Journalists have asked the security service of Ukraine, interior minister and chairman of the national police to respond to the information UP has gathered.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

[/vc_column_text][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1478786551399-adbbd256-7b8d-7″ taxonomies=”6564″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

2 Nov 2016 | Belarus, Europe and Central Asia, Russia, Ukraine

Today is the International Day to End Impunity for Crimes Against Journalists. Since 2006, 827 journalists have been killed for their reporting. Nine out of 10 of these cases go unpunished.

Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom platform verified a number of reports of impunity since it began monitoring threats to press freedom across Europe in May 2014. Here are just five reports from three countries of concern: Russia, Belarus and Ukraine.

“Impunity empowers those who orchestrate crimes and leaves victims feeling vulnerable and abandoned,” said Hannah Machlin, Index’s project officer for MMF. “What we are witnessing is a vicious cycle of unresolved crimes against journalists.”

Most recently, MMF reported that Sergey Dorovskoy, who the Lyublinski district court in Moscow recognised as orchestrating the murder of Novaya Gazeta journalist Igor Domnikov, received a 200,000 rubles (€2,860) fine but no jail time because the statute of limitations had passed. This small punishment was in compensation for “moral damages” to Domnikov’s wife.

From 1998-2000, Igor Domnikov headed Novaya Gazeta’s special projects department which ran investigations. He had published a series of articles about Dorovskoy’s alleged criminal activities and corruption.

On 19 February 2014, Vyacheslav Veremiy, a Ukrainian journalist for the newspaper, Vesti, died from injuries he sustained from a gunshot and a brutal beating. Veremiy was targeted while covering the anti-government Euromaidan protests in the country’s capital Kyiv. The two-year-old case has produced suspects but no prosecutions. The investigation remains open.

The year ended with an attack on the editor-in-chief of the news website Taiga.info, Yevgeniy Mezdrikov in Russia. Two individuals posed as couriers to gain access to the offices, where they assaulted Mezdrikov. After just one year the offender was granted a pardon.

In Ukraine, on 21 January 2015, Rivne TV journalists Arten Lahovsky and Kateryna Munkachi were physically attacked. The assailants released an unknown substance from a gas canister, choking Lahovsky. The journalists believe the attack to be premeditated and have criticised police failure to investigate.

In Belarus, officials did not file a criminal case in the assault of TUT.by journalist Pavel Dabravolski, who said he was beaten on 25 January 2016 by police while filming another incident at a court facility. The officers involved testified that Dabravolski did not present a press card when requested and grabbed at them while shouting insults. Additionally, police claimed that Dabravolski was interfering with their duties.

Dabravolski captured the incident on his mobile phone, though the recording was not considered as part of the three-month investigation into the incident. According to the journalist, he was thrown to the ground and kicked by police. He was fined for charges of contempt of court and disobeying legal demands.

Index on Censorship calls for more to be done to ensure justice is served for crimes against journalists.

1 Nov 2016 | Belarus, Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News

On 11 September, the people of Belarus elected the lower house of parliament, the House of Representatives.

Speaking about the media environment surrounding the elections, the United Nations special rapporteur on human rights in Belarus, Miklós Haraszti, said: “It is regrettable that Belarus did not take into account real changes towards equal media access, verifiable turnout, honest vote count, and a pluralistic parliament. These changes have been recommended for many years by the OSCE, and my own reports.”

As in previous elections, independent journalists were denied access to information about the work of electoral commissions. On 10 August, during a district election commission meeting in the town of Barysau, the deputy chairman refused to answer a question about the candidates for the lower chamber of the Belarusian parliament posed by editor-in-chief of local independent newspaper Borisovskiye novosti, Anatol Bukas. A complaint filed by Bukas to the Central Election Commission was dismissed.

On election day, a correspondent for the independent newspaper Nasha Niva was forbidden to take photos at the polling station where the president of Belarus, Alexander Lukashenka, was supposed to vote. Security guards in civilian clothes said the journalist had not been accredited.

Opposition candidates faced arbitrary bans and censorship in publishing their “election programmes”, which lay out their platforms. Under Belarusian law, state-run media outlets should give an equal opportunity to all candidates to publish their programmes, but editors of state-run media refused to publish some which contained criticism of the authorities. The candidates referenced the election law, but have not been told of any specific violations in the texts. Complaints by the MP candidates have not been responded to by officials.

State-run newspaper Vecherniy Minsk refused to publish an election programme by opposition activist and Belsat TV’s anchorman Yury Khashchavatski. Vecherniy Minsk’s editor-in-chief Syarhei Protas wrote that the election programme “cannot be published because it does not comply with the requirements of Articles 47 and 75 of the Electoral Code of the Republic of Belarus”.

These articles state that “a candidate’s program must not contain propaganda for war, incitement to violent change of the constitutional order or violation of territorial integrity of the Republic of Belarus, to social, national, religious and racial hatred”.

A candidate’s programme must also not encourage or call up to obstruction, cancellation, or postponement of elections and there should be no insults or slandering against Belarusian officials or other candidates. However, the editor of Vecherniy Minsk did not indicate which statements of Khashchavatski were supposedly illegal.

According to Yury Khashchavatski, he never violated the law in his election programme and the editor might not have liked some his words about president Lukashenka.

A candidate from the United Civil Party Mikalay Ulasevich found himself in the same situation when local state-run newspaper Astravetskaya Prauda in Astravets, in Hrodna region, refused to publish his election programme referring to the same grounds. Moreover Hrodna regional state television did not broadcast Ulasevich’s speech. In his address to electors, which was recorded but not aired at the scheduled time, Ulasevich opposed the construction of a nuclear power plant in Belarus and spoke about a corruption problem in the country. Mikalay Ulasevich is behind the public initiative Astravets Nuclear Power Plant Is A Crime. According to Belarusian law, all candidates have a right to broadcast election speeches on state-run TV during the election campaign.

Giving an assessment of media freedom during the last parliamentary election Andrei Bastunets, Chairperson of BAJ, said: “We explain some easing of pressure on journalists during the elections with the desire of the Belarusian authorities to obtain a positive assessment of the election campaign by the international structures. It follows on the need to seek credits in the conditions of economic crisis and does not expel resumption of the previous practice of persecution of journalists after the elections.”

Each week, Index on Censorship’s

Each week, Index on Censorship’s