29 Jul 2016 | Bosnia, Europe and Central Asia, Macedonia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features, Poland, Turkey, United Kingdom

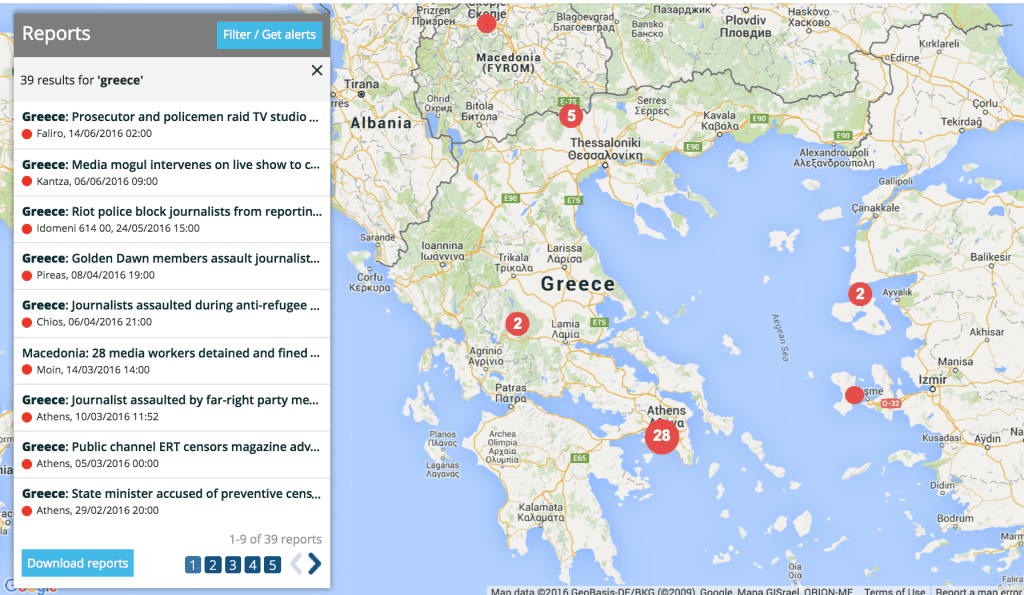

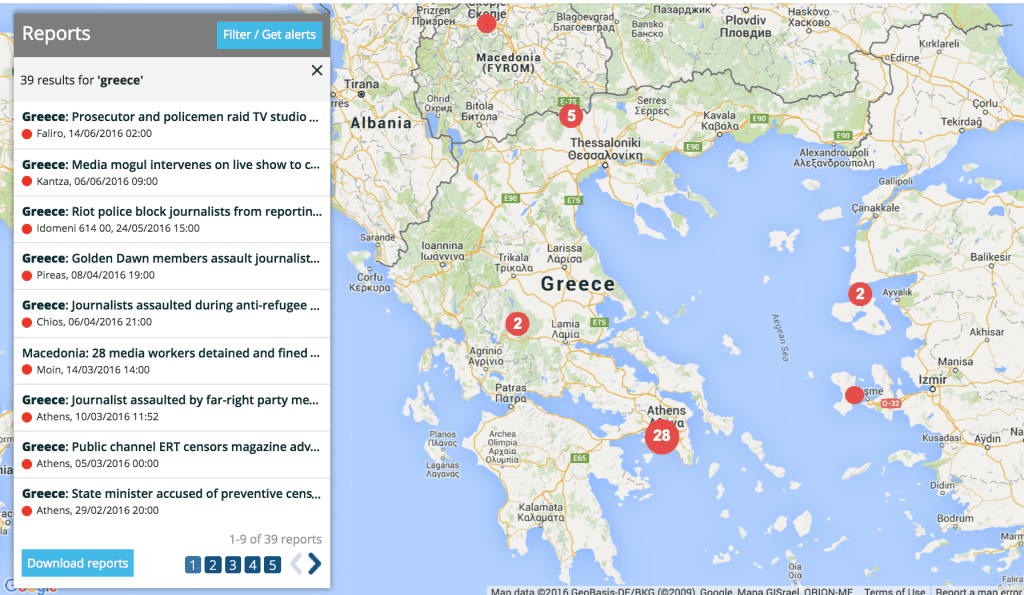

Click on the dots for more information on the incidents.

Each week, Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project verifies threats, violations and limitations faced by the media throughout the European Union and neighbouring countries. Here are five recent reports that give us cause for concern.

Turkey: Warrants issued for arrest of 89 journalists

Turkish authorities have issued two lists of journalists to be arrested since the 15 July failed military coup attempt in the country. Firstly, on 25 July, authorities issued the names of 42 journalists as part of an inquiry into the coup attempt. Well-known commentator and former parliamentarian Nazli Ilicak was among those for whom a warrant was issued, as was Ercan Gun, the head of news department at Fox TV in Turkey.

Two days later, 27 July, authorities issued warrants for the detention of 47 former executives or senior journalists of the newspaper Zaman. The arrests were part of a large-scale crackdown on suspected supporters of US-based Muslim cleric Fethullah Gulen, accused by Ankara of masterminding the failed coup. The authorities shut down Zaman in March. At least one journalist, former Zaman columnist Şahin Alpay, was detained at his home early on Wednesday.

26 July, 2016 – Media Print Macedonia, the publisher of several daily and weekly newspapers, announced that it would dismiss 20 staff members, mostly experienced journalists and former editors from the daily Vest.

Layoffs are also to include employees from daily Utrinski Vesnik, Dnevnik, Makedonski Sport and weekly magazine Tea Moderna.

MPM stated layoffs were prompted by bad results and that the decision on who to dismiss would be based on the company’s internal procedures. Employees who lose heir jobs are to be compensated from one up to five average salaries, TV Nova reported.

24 July, 2016 – Emir Talirevic, a doctor who owns Moja Klinika, a private healthcare institution in Sarajevo, used Facebook to insult Selma Ucanbarlic, a journalist for the Centre for Investigative Journalism, following her articles about Moja Klinika, regional TV outlet N1 reported.

On 24 July Talirevic wrote on Facebook, among other things, that “judging by her psycho-physical attributes [the journalist] should never be allowed to do more complex work than grilling a barbecue”. He alleged hers were “imbecilic findings”, adding that “her work requires higher IQ than 65”.

In a second post, published on 27 July, Talirevic wrote that “as the toilet tank is taking away my associations on Selma and her CIN(ical) website I am thinking about the oldest profession in the world – prostitution”. He also wrote: “CIN is financed by gifts, like prostitutes”, and “after today’s article at least we know for whom Selma Ucanbarlic and her CIN colleagues are spreading their legs”.

22 July, 2016 – Masza Makarowa, a former journalist for the Russian language division of national broadcaster Polskie Radio, left the station due to a repressive climate and censorship, she claimed on her Facebook page.

An “atmosphere of scare tactics and paranoia” was prevalent at the broadcaster, Makarowa said. She also claimed that the station management instructed staff on which sources to consider for publication to Russian-speaking audiences, approving right-leaning, pro-governmental websites while explicitly prohibiting liberal sources like Gazeta Wyborcza for being opinionated. Certain updates, furthermore, were removed from the website.

22 June, 2016 – Jeff Howell, who had been writing a home maintenance advice column for The Telegraph for 17 years, was allegedly dismissed and removed from the Telegraph website after comments he made to his property section editor, Anna White.

According to Private Eye, the column, which was initially published both on the website and online, was removed from the website after he made a joke to property section editor White about correcting the Telegraph’s editing errors following a typo in January. Much of the column’s online archive was deleted following the incident.

Howell’s page on the Telegraph website used to get up to 10,000 hits daily but the removal of most of his columns from the website “made it easy to justify his dismissal by saying he didn’t produce any online traffic”.

26 Jul 2016 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, News and features, Ukraine

Pavel Sheremet (Photo: Ukrainska Pravda)

The death of Pavel Sheremet on Wednesday 20 July is the latest and most egregious example of violence against journalists in Ukraine, according to verified incidents reported to Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project.

Sheremet was killed when the car he was driving exploded on the morning of 20 July in Kyiv. In a statement, Ukrainian police said that an explosive device detonated at 7.45am as Sheremet was driving to host a morning programme on Radio Vesti, where he had been working since 2015.

The car belonged to Sheremet’s partner, journalist Olena Prytula, who co-founded Ukrainska Pravda with murdered journalist Georgiy Gongadze.

Sheremet had been imprisoned by Belarusian authorities in 1997 for three months before being deported to Russia. Though stripped of his citizenship in 2010, he continued to report on Belarus on his personal website. He moved to the Ukrainian capital in 2011 to work for the newspaper Ukrainska Pravda.

A review of Mapping Media Freedom data from 1 January to 20 July found 41 attacks on journalists — including physical violence, injuries and seizure or damage to equipment and property of journalists — have taken place in Ukraine since the beginning of the year. The largest number of incidents – about one-third – occurred in Kyiv. More than half of these journalists were attacked by unknown assailants, while the names of perpetrators in a third of these incidents are known. In about one in three cases, the attacks were committed by representatives of local authorities.

While impunity remains a key issue in Ukraine contributing to violence against journalists, the situation is slowly beginning to change for the better compared to previous years. According to the Institute of Mass Information, a positive trend has been spotted since the beginning of the year: There has been a slight increase in the number of cases involving violation of the journalists’ rights submitted to courts. In particular, there were 11 such cases in 2015. Meanwhile, 12 such cases were submitted to court for the first quarter of 2016 alone.

Despite the improvement in prosecutions, journalists are continuing to be subject to violence and intimidation.

In June, a series of incidents occurred in Berdiansk in the Zaporizhzhia region.

On 10 June Volodymyr Holovaty, a journalist working for Yuh TV, and his cameraman, Anatoliy Kyrylenko, were physically assaulted at a recreation center in Berdiansk Spit. A group of people in camouflage set upon them without warning. The attackers swore, demanded that filming stop, took the camera, stole a data storage device and struck the journalist and the cameraman, who were taken to a hospital.

On 7 June, during a rally at the Berdiansk courthouse, an unknown person harassed cameraman Bohdan Ivanuschenko and journalist Volodymyr Dyominof, who both work for Yuh TV. In that incident the individual interfered with their filming of a report with obscene language and threatened the media professionals with physical violence.

In response, journalists staged a rally on 13 June to bring attention to the recent threats and assaults in the town and demand a stronger police response. The journalists wrote an open letter demanding prosecutors help protect the rights of media workers in the town.

In May physical attacks took place in Kherson, Kyiv, Mariupol, Mykolayiv, Kharkiv, Marhanet, Zaporizhzhia and Zirne.

In the Kyiv incident, photographer and cameraman Serhiy Morhunov, who covers the conflict in eastern Ukraine, was assaulted on 22 May by unknown assailants. The journalist suffered serious head injuries including a brain haemorrhage, fractured lower jaw and partial memory loss. The doctors described his condition as serious. Morhunov was not robbed during the attack.

In Zaporizhzhia Anatoliy Ostapenko, a journalist working for Hromadske TV, who reported on corruption allegedly involving regional officials, was assaulted by masked individuals on 24 May. The journalist was walking to work when he was cut off by a car with tinted windows and lacking a license plate. Three masked men exited the car, knocked Ostapenko to the ground and physically assaulted him. Ostapenko suffered numerous bruises.

On 25 May, in Kherson, Taras Burda, the husband of a member of the Suvorivsky district council, attacked Serhiy Nikitenko, a journalist for Most media and the representative of NGO Institute of Mass Information in the region, with a tablet computer during an altercation. Burda told IMI that the journalist had attacked him first.

Many attacks have been directed at the property or equipment of journalists. In the village of Lebedivka in the Odesa region, poachers threatened the crew of the Channel 7 investigative programme Normal. The individuals pierced the tires of the journalists’ car by laying spike strips and threw eggs at the vehicles. The incident occurred when the crew was filming a TV report about the activities of poachers in the Tuzla Coastal Lakes national reserve.

On 1 April, in the town of Konotop in the Sumy region, unknown persons threw Molotov cocktails at local TV studio. A similar incident occurred in Kyiv on April 22 when 15 unidentified people attacked the office of the Ukraine TV channel. They poured red paint in the channel’s lobby and left a print out reading “Blood will be spilled!”

In April, several assaults on journalists took place in Kyiv (journalists of 1+1 TV channel were attacked), and in the village of Lymanske in Odesa region.

Only one attack on journalists was recorded in February. However, it was a flagrant incident in the context of physical violence. In Kharkiv, representatives of the Hromadska Varta organisation attacked Stanislav Kolotilov and Lesya Kocherzhuk, journalists for the Kharkiv News portal. Kolotilov suffered a concussion and spinal injury. Kocherzhuk was burned on the hand with a cigarette. The journalists were investigating allegations of illegal construction connected to the Hromadska Varta.

Also in February, representatives of the Azov civil corps blocked the premises of the Inter TV channel. The blockade participants tried to enter the office, threw debris at it and painted the doors black.

In January, journalistic activity was obstructed in Zhytomyr during a conflict involving the Zhytomyrski Lasoshchi confectionery factory. Guards prevented reporters from Channel 5 and UA1 local online media outlet from filming. A microphone was snatched from Channel 5 journalist and a camera was damaged.

Also in January, assaults on journalists, as well as attacks on journalists’ property occurred in Ternopil, Kyiv, Mykolayiv and Odesa, as well as in the village of Dovzhanka in the Ternopil region and the town of Karlivka in the Poltava region.

On 11 January 2016, the windows of a car belonging to journalist Svitlana Kriukova were smashed by unknown perpetrators but nothing was stolen from the vehicle. Kriukova was writing a book on Hennadiy Korban, a politician and businessman said to be close to oligarch Ihor Kolomoyskiy. Korban was under investigation for alleged criminal offences including kidnapping and theft. The incident occurred when the Kriukova was visiting Korban at the hospital and she believes the damages are linked to her professional activities.

23 Jul 2016 | Academic Freedom, Campaigns -- Featured, Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

It was at the early hours of Friday that a journalist sent a note to her colleagues.

It was at the early hours of Friday that a journalist sent a note to her colleagues.

“We are told by the management that our publication is discontinued with immediate effect,” she said. “We are told to pack our belongings and leave the office. You can’t imagine how sad I am.”

The weekly news magazine Nokta, which had been launched in the aftermath of a military coup in 1980s, is no more.

Lately, under a new management, Nokta belonged to the critical mass of what remained of independent journalism in Turkey, with long reads and popular, bright commentators such as Perihan Mağden and Gükhan Özgün.

My colleague went on to say that the management internal communique cited the loss of a printing house as the reason for the closure. Given the waves of restriction over basic freedoms in the wake of Emergency Rule declared in 81 provinces of Turkey, this explanation came as no surprise.

Commenting on the closure, a Kurdish colleague who has extensively covered the operations in Cizre and Diyarbakır, added: “It’s a disaster to have the media outlets shut down, but it’s even worse to see media professionals left without a job.”

In another incident, Paolo Brera, a well-known reporter with La Repubblica, was held by the police officers at Sultanahmet Square yesterday while interviewing tourists, and taken to police headquarters. At first his whereabouts were unknown, and Italy had to intervene at the highest level to have him released after four hours.

As of Friday afternoon the situation of the columnist and human rights lawyer Orhan Kemal Cengiz was unclear. Cengiz is an international figure and close friend of the Kurdish lawyer Tahir Elçi who was assassinated in Diyarbakır last summer. Among other assignments, Cengiz followed the case of Christian missionaries slain in Malatya in 2007. He attended the UN’s Human Rights Summit in Geneva some months ago, commemorating by explaining the situation to a larger audience. His colleagues are on standby, knowing that he is held at the Anti-Terror Unit in Istanbul. His wife, also a lawyer, had been told that the detention was related to a case from 2014, but nobody has any further details.

The Emergency Rule means that no lawyers other than those appointed by the bar associations are now allowed to have access to all the cases. What is also known is that those who are arrested are held in cells at police headquarters.

Justice Minister Bekir Bozdağ said in an interview yesterday that in “crimes related to terrorist activities” individuals can be detained for at least seven-to-eight days. “Our staff is working on the possibilities of even extending that time,” he said, adding that he shares the concern that it will be very difficult to distinguish innocents from criminals.

The overall situation continues to be opaque, with scarce information, and experienced journalists caution each other to compare what’s being officially stated with what’s really being done. The measures so far leave little doubt that the media and the academia are under severe pressure, and the growing concern is there is an escalation of a clampdown, without much explanation of what the media and academic freedom had to do with the very coup attempt itself.

A version of this article was originally posted to Suddeutsche Zeitung. It is published here with permission of the author.

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

19 Jul 2016 | Europe and Central Asia, Greece, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features

As Greece tries to deal with around 50,000 stranded refugees on its soil after Austria and the western Balkan countries closed their borders, attention has turned to the living conditions inside the refugee camps. Throughout the crisis, the Greek and international press has faced major difficulties in covering the crisis.

“It’s clear that the government does not want the press to be present when a policeman assaults migrants,” Marios Lolos, press photographer and head of the Union of Press Photographers of Greece said in an interview with Index on Censorship. “When the police are forced to suppress a revolt of the migrants, they don’t want us to be there and take pictures.”

Last summer, Greece had just emerged from a long and painful period of negotiations with its international creditors only to end up with a third bailout programme against the backdrop of closed banks and steep indebtedness. At the same time, hundreds of refugees were arriving every day to the Greek islands such as Chios, Kos and Lesvos. It was around this time that the EU’s executive body, the European Commission, started putting pressure on Greece to build appropriate refugee centres and prevent this massive influx from heading to the more prosperous northern countries.

It took some months, several EU Summits, threats to kick Greece out of the EU free movement zone, the abrupt closure of the internal borders and a controversial agreement between the EU and Turkey to finally stem migrant influx to Greek islands. The Greek authorities are now struggling to act on their commitments to their EU partners and at the same time protect themselves from negative coverage.

Although there were some incidents of press limitations during the first phase of the crisis in the islands, Lolos says that the most egregious curbs on the press occurred while the Greek authorities were evacuating the military area of Idomeni, on the border with Macedonia.

In May 2016, the Greek police launched a major operation to evict more than 8,000 refugees and migrants bottlenecked at a makeshift Idomeni camp since the closure of the borders. The police blocked the press from covering the operation.

“Only the photographer of the state-owned press agency ANA and the TV crew of the public TV channel ERT were allowed to be there,” Lolos said, while the Union’s official statement denounced “the flagrant violation of the freedom and pluralism of press in the name of the safety of photojournalists”.

“The authorities said that they blocked us for our safety but it is clear that this was just an excuse,” Lolos explained.

In early December 2015, during another police operation to remove migrants protesting against the closed borders from railway tracks, two photographers and two reporters were detained and prevented from doing their jobs, even after showing their press IDs, Lolos said.

While the refugees were warmly received by the majority of the Greek people, some anti-refugee sentiment was evident, giving Greece’s neo-nazi, far-right Golden Dawn party an opportunity to mobilise, including against journalists and photographers covering pro- and anti-refugee demonstrations.

On the 8 April 2016, Vice photographer Alexia Tsagari and a TV crew from the Greek channel E TV were attacked by members of Golden Dawn while covering an anti-refugee demonstration in Piraeus. According to press reports, after the anti-refugee group was encouraged by Golden Dawn MP Ilias Kasidiaris to attack anti-fascists, a man dressed in black, who had separated from Golden Dawn’s ranks, slapped and kicked Tsagari in the face.

“Since then I have this fear that I cannot do my work freely,” Tsagari told Index on Censorship, adding that this feeling of insecurity becomes even more intense, considering that the Greek riot police were nearby when the attack happened but did not intervene.

Following the EU-Turkey agreement in late March which stemmed the migrant flows, the Greek government agreed to send migrants, including asylum seekers, back to Turkey, recognising it as “safe third country”. As a result, despite the government’s initial disapproval, most of the first reception facilities have turned into overcrowded closed refugee centres.

“Now we need to focus on the living conditions of asylum seekers and migrants inside the state-owned facilities. However, the access is limited for the press. There is a general restriction of access unless you have a written permission from the ministry,” Lolos said, adding that the daily living conditions in some centres are disgraceful.

Ola Aljari is a journalist and refugee from Syria who fled to Germany and now works for Mapping Media Freedom partners the European Centre for Press and Media Freedom. She visited Greece twice to cover refugee stories and confirms that restrictions on journalists are increasing.

“With all the restrictions I feel like the authorities have something to hide,” Aljari told Index on Censorship, also mentioning that some Greek journalists have used bribes in order to get authorisation.

Greek journalist, Nikolas Leontopoulos, working along with a mission of foreign journalists from a major international media outlet to the closed centre of VIAL in Chios experienced recently this “reluctance” from Greek authorities to let the press in.

“Although the ministry for migration had sent an email to the VIAL director granting permission to visit and report inside VIAL, the director at first denied the existence of the email and later on did everything in his power to put obstacles and cancel our access to the hotspot,” Leontopoulos told Index on Censorship, commenting that his behaviour is “indicative” of the authorities’ way of dealing with the press.

It was at the early hours of Friday that a journalist sent a note to her colleagues.

It was at the early hours of Friday that a journalist sent a note to her colleagues.