14 Jan 2016 | Italy, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features, Vatican

Two Italian journalists are being prosecuted by The Vatican for revealing confidential information and could face up to eight years in prison.

Emiliano Fittipaldi and Gianluigi Nuzzi are being tried in the so-called “Vatileaks II” case for publishing leaked documents in their books detailing financial misdeeds involving The Holy See. Fittipaldi is the author of Avarice and Nuzzi’s is entitled Merchants in the Temple.

The criminal trial by the Vatican justice against the reporters is a serious one. The journalists are accused of violating “Crimes against the Fatherland” in the Vatican penal code, specifically a 2013 amendment that added section 116, which says “whoever procures illegally or reveals information or documents whose disclosure is forbidden, shall be punished with imprisonment from six months to two years or with a fine from thousand to five thousand euro”. But “if the conduct has related to information or documents concerning the fundamental interests or diplomatic relations of the Holy See and the State, punishment of imprisonment is implemented from four to eight years”.

Fittipaldi and Nuzzi are not the only people standing trial in the case. The alleged sources of the internal Vatican documents — Lucio Vallejo Balda, secretary of Cosea, the commission that conducted the survey on the finances of the Vatican, and Francesca Immacolata Chaouqui, a member the commission — are also in the dock. A fifth person, Nicola Maio, a former contributor to Cosea, is also being prosecuted. Balda, Chaouqui and Maio are also accused of criminal association.

So far, there have been three hearings as part of the trial. The first on 24 November ended with a decision by the court to reject requests for deferral submitted by the defendants, who said they didn’t have enough times to organise their defence, having received court documents only the day before. The second hearing on 30 November lasted only 13 minutes, during which the court deferred the trial until 7 December. On that day, the court admitted all the witnesses requested by the defence.

“I am a journalist, and when a reporter has some news and verifies it, he must publish it”, Fittipaldi said of the Vatican’s decision to prosecute. After the second hearing, Nuzzi said: “It is a Kafkian process, in which the elements of surrealism occasionally fall on the stage of the case. I do not share the codes of this process, we are talking about a process to press freedom.”

Press freedom organisations have been quick to express solidarity with the journalists and called on the Vatican to end the proceedings. The FNSI (National Federation of Press in Italy) called the disputed allegations “paradoxical”. Dunja Mijatović, the OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media, asked the Vatican, which is a member of the OSCE, to withdraw the criminal charges set against the reporters. The CPJ (Committee to Protect Journalists) called on Vatican to drop the charges against Nuzzi and Fittipaldi. EFJ (European Federation of Journalists) said: “Journalists must be free to investigate and report about the use of public money. The protection of their sources is also part of the ethical code of journalists.”

The next hearing of the case has yet to be scheduled.

6 Jan 2016 | Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features, Serbia

It was a Wednesday morning in early November when investigative journalist Slobodan Georgijev opened Informer, one of Serbia’s notorious tabloids. He had just arrived at his office, the newsroom of Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN), one of Serbia’s few independent media outlets. When he turned the page he was shocked by what he saw; a picture of his own face amongst two others, in an article calling three media outlets known for critical reporting of the Serbian government, including BIRN, “foreign spies”.

“It was funny and unpleasant at the same time,” Georgijev recalled, speaking to Index on Censorship. “Funny because I knew that this is just a campaign by Informer to undermine the credibility of independent journalists.” More importantly, he had begun worry about his own safety. “It’s also unpleasant because you never know how people will interpret such defamations.”

Several independent media houses — including BIRN, as well as Crime and Corruption Reporting Network (KRIK) and Center for Investigative Journalism Serbia (CINS) — have alleged that pro-government tabloids like Informer are running a smear campaign against them.

The first major incident followed the publication of a story about the cancellation of Prime Minister Aleksandar Vucic’s vacation in August 2015. Informer published an article saying that Vucic was forced to cancel his two day vacation in Serbia due to reporters from BIRN and CINS allegedly booking a room next to his.

The same newspaper also wrote that BIRN and CINS were meeting with European Union representatives on a weekly basis to plan to bring down the government.

“We are basically accused of being financed by the EU to work against our government,” Branko Cecen, director of CINS, told Index on Censorship. Cecen, like Georgiev, was also pictured and called a foreign spy in Informer. “Expressions like ‘foreign mercenaries’ and ‘joint criminal activity against their own state’ have been used.”

Informer newspaper is openly affiliated with the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) of prime minister Aleksandar Vucic and has frequently been accused of political bias in favour of the party and the prime minister.

CINS, KRIK and BIRN have long reported on what they see as a slew of regular negative articles about themselves in tabloid newspapers with close ties to the government. There is no doubt that the three news outlets are targets because of their critical reporting on the government.

One of BIRN’s stories revealed a contract the Serbian government had signed with the national carrier of United Arab Emirates, Etihad Airways, to take over it’s state-owned counterpart Air Serbia. The deal had been financially damaging for Serbia, which was kept from the public until BIRN obtained and published the contract.

Another story investigated alleged corruption concerning a project for pumping out a flooded coal mine. BIRN found out that Serbia’s state-owned power company had awarded a contract to dewater the mine to a company who’s director is a close friend of the prime minister.

The coal mine revelations led to an angry speech about BIRN by Vucic on national television saying: “Tell those liars that they have lied again(.”

He also attacked the EU delegation in Serbia for being involved in discrediting the government by financing BIRN. “They got the money from Davenport and the EU to speak against the Serbian government,” the prime minister said, naming Michael Davenport, the head of the EU delegation in Belgrade.

BIRN’s editor-in-chief Gordana Igric told Index on Censorship she sees a resemblance to Serbia’s difficult nineties. “This reminds me of the regime of Slobodan Milosevic, a time when the prime minister also had a prominent role and critical journalists and NGOs were marked as foreign mercenaries,” she said. “What’s happening in Serbia today makes you feel sad and confused.”

Independent journalists find the path that the prime minister is taking alarming. Some compare him with the Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdoğan or the Russia’s Vladimir Putin. According to Cecen, the level of freedom of expression is at the lowest level since the time of strongman Milosevic. “There is an aggressive campaign against anybody and anything criticising the prime minister and his policies”, he said. “The prime minister has taken over most media in Serbia, especially national TV networks, but also local ones. His small army of social media commentators is terrorising the internet. It is quite bleak and frustrating.”

Regardless of Vucic’s verbal attacks towards the EU delegation, Serbia has opened the first two chapters in its EU membership negotiation in December 2015. This represents a big step towards eventual membership of the European Union. But the latest progress report on Serbia (November 2015) says the country needs to do much more in terms of fighting corruption, the independence of the judiciary and ensuring media freedom.

“The concern over freedom of expression is always expressed in these reports,” Cecen said. “But we see no influence of such reports since situation with media and freedom of expression is deteriorating daily.” Cecen is disappointed in the European Union’s support for independent media in Serbia and finds that EU officials show too much support for the Serbian government and the prime minister.

After he had seen his own face in the paper, Georgiev picked up the phone and called up Informer’s editor-in-chief Dragan Vučićević to ask for a better picture in the next paper. Georgiev jokes about it and clearly doesn’t let accusations and threats hold him back. “People around me are making jokes”, he said. “They call me a foreign mercenary, an enemy of the state.”

Georgiev pressed charges for defamation against Informer. “We are living in a state of constant emergency,” he continued, concerned about the state of press freedom in his country. “Serbia is not like Turkey. But it goes very fast in that direction.”

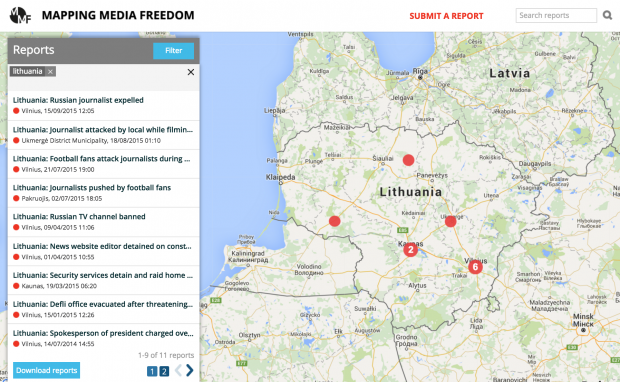

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

5 Jan 2016 | Lithuania, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features

RTR Planeta, a Russian language channel broadcasting in Lithuania, has repeatedly run into conflict with the country’s television regulator.

In December, the Lithuanian Radio and Television Commission ordered RTR Planeta to be moved to paid TV packages after it broadcast material that the agency said instigated racial hatred and warfare. The programme in question was the 29 November episode of Sunday Evening with Vladimir Solovyov, which discussed the downing of a Russian plane by the Turkish airforce.

Russian MP Vladimir Zhirinovsky, who was a guest on the programme, said Turkish people were “a nation of wild barbarians,” and said that Turkey should be “brought to its knees” through military attacks.

“We need an air raid on any part of Turkey (…), the Turkish army must be destroyed,” said Zhirinovsky.

This is the second time the programme has prompted the regulator to take action. In April 2015, RTR Planeta was blocked from broadcasting for three months for allegedly “inciting discord and warmongering” over the conflict in Ukraine.

The content in question included a tirade against the Baltic countries by ultra-nationalist Russian politician Vladimir Zhirinovsky on the Sunday Evening With Vladimir Solovjev programme. Zhirinovsky said that Poland and the Baltic states would be “wiped out” should a war break out between Russia and NATO.

Although Lithuanian politicians and media experts agreed on the inflammatory nature of RTR Planeta content, especially the comments made by Zhirinovsky, some media pundits have expressed doubt over the decision to shut the channel down for three months. It resumed broadcasting on 13 July 2015.

In April, Audris Matonis, news service director at Lithuania’s national LRT broadcaster, rejected criticism that the ban was excessive and amounted to censorship. He insisted that “all should realise that what they’re advocating is non-compliance with Lithuanian law”.

But Gintautas Mazeikis, director of the Political Theory Department at Vytautas Magnus University in Kaunas, took issue when speaking to Delfi.lt. “Do we want and seek diplomatic and other means to influence Russian channels, or are we only trying to co-operate with cable TV service providers so they change their packages and broadcast more Polish or Ukrainian TV?” he said. “Do we want to explain and encourage critical thinking among speakers of Ukrainian, Belarusian, Russian and Polish who live in Lithuania?”

Aidas Puklevičius, a journalist and author, insisted that the broadcast ban may not have been the best decision and reasoned that the situation should improve once the generation of people who speak only Russian as a foreign language gives way to one which is more fluent in English.

“Russia will then lose its only vehicle for exporting soft power, something it has very little of,” Puklevičius said to Delfi.it. “Russia did not invent Pepsi Cola, nor jeans, nor Hollywood. Russia’s only strength is its ability to play on Soviet nostalgia.”

Media professionals in Lithuania have increasingly found themselves taking sides in the Ukraine conflict.

“Unfortunately, Russia-Ukraine warfare has become part of journalism in Lithuania and not surprisingly, all the Lithuanian news, except for some reports on the State Lithuanian TV, are concerned with the same issue: how atrocious the Kremlin-backed Russian insurgents are and how courageous the Ukrainians are,” a Lithuanian journalist, who agreed to speak on the condition of anonymity, told Index on Censorship. “Why is it happening? In any warfare, you’d expect analysis and different points of view, but none of it could be found on Lithuanian TV.”

The journalist said he had stopped watching Lithuanian TV news and has switched to German TV channels which air many different views on the conflict.

In January 2015, Dainius Radzevicius, the chairman of Lithuania’s Union of Journalists, wrote a commentary piece in which he said “polarisation of the media is something we all have to admit is happening, and it has been very palpable for the last couple of years not only in the Lithuanian media but elsewhere too”.

Radzevicius said the problem began as a result of economic conditions, but it is fueled by the geopolitical situation, including the conflict in Ukraine.

“Against this backdrop, we may now have less of a variety of opinions on the radio waves, the TV screens or the newspaper pages; but it is necessary to resist the powerful and obtrusive propaganda coming from the East, therefore, what I call our ‘white propaganda’ is necessary during the times,” he said in the piece.

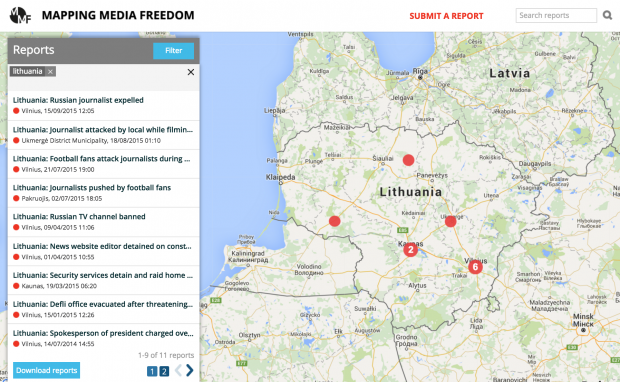

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

4 Jan 2016 | Campaigns, Mapping Media Freedom, Poland

Update: President Andrzej Duda of Poland signed the new law into effect on 7 January, 2016.

The undersigned press freedom and media organisations – European Federation of Journalists (EFJ), European Broadcasting Union (EBU), Association of European Journalists (AEJ), Reporters Without Borders (RSF), Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) and Index on Censorship – are outraged by the proposed bill, hastily introduced by the majority party in Poland on 29 December 2015 for immediate adoption, without any consultation, abolishing the existing safeguards for pluralism and independence of public service media governance in Poland.

The introduction of a system whereby a government minister can appoint and dismiss at its own discretion the supervisory and management boards goes against basic principles and established standards of public service media governance throughout Europe. If the Polish Parliament passes these measures, Poland will create a regressive regime which will be without precedent in any other EU country.

We consider that the proposed measures will represent a retrograde step making more political, and thus less independent, the appointment of those in charge of the governance of public service media in Poland.

We urge the Polish authorities to resist any temptation to strengthen political control over the media.

To date, Poland can boast an excellent track record in terms of freedom of the media, which ranks in the top category in the Reporters without Borders World Press Freedom Index 2015 as well as in the 2015 Freedom House report on political rights and civil liberties.

TVP reaches more than 90% of the Polish population every week and had about 30% of the TV broadcasting market in Poland in 2014, which is higher than in the case of most public TV channels in Central and Eastern Europe.

Signatories

European Federation of Journalists (EFJ)

European Broadcasting Union (EBU)

Association of European Journalists (AEJ)

Reporters Without Borders (RSF)

Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ)

Index on Censorship

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/