4 Jan 2016 | Estonia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News

In late November 2014, Estonia’s parliament made a historic decision to launch a Russian-language TV-channel as part of ERR, Estonia’s public broadcaster. A year later the channel is a reality: ETV+, ERR’s third channel debuted on 28 September.

The launch passed quite quietly, compared to the reaction that greeted the decision to create the channel. There were discussions about what the opening of a Russian-language channel in Estonia would mean. Would it be a tool of government propaganda or a knitting together of Estonia’s two communities, Estonian and Russian speakers into one community? From Russia there were clear expectations of a counter-weight to Russian media, which is widely followed by Estonia’s Russian speakers.

Speaking at a media conference hosted by ERR in June 2015, the ETV+ chief editor Darja Saar — a Russian project manager with no media experience — described the goals of the new channel: “We gave up the classical media rules from the very beginning, when we decided that we are not going to tell people what is right or wrong. Instead, we will follow people’s wishes – they are tired of just words and want deeds.”

The new TV channel aims not only to be an informer, educator and entertainer in the mould of a classical public service broadcasting channel but a leader in society and a hands-on problem solver.

In its two months on air, though, ETV+ has operated mostly as a traditional TV-channel offering morning programmes, debates, films and news. As required by law, all programmes are subtitled in Estonian. While geared toward Estonia’s Russian speakers, the station’s audience is mostly ethnic Estonians. In its debut week, ETV+ attracted 294,000 viewers. Ethnic Estonians accounted for 217,000 of the total and the other 77,000 were other ethnicities. On an average day during its first week 97,000 watched ETV+. On 28 September, its first day, 120,000 tuned in to sample the new station’s offerings.

ERR board member Ainar Ruussaar pointed out that ETV+ is a long-term project to improve Estonian society and was not about ratings. Yet the failure to draw a larger share of the Russian-speaking audience in the country may put that mission in jeopardy.

ERR has a fraught history with Russian-language programming. Promotion of Estonian language and culture has always been one of its core values. This served it well while it was under the Soviet system. Later, it countered Russian propaganda. But while times changed, ERR did not sufficiently move away from its core. In the early 2000s, the broadcaster, then under budgetary pressures, cut its slate of offerings in Russian. For years after its sole Russian-language production was a little-watched news programme.

In 2007, there was a serious discussion about launching a new Russian-language station after the 27 April violence sparked by the removal of the Bronze Soldier, a World War II memorial in Tallinn’s city centre. Then the political decision in favour of the Russian-language channel in Estonian Television was only one step away and there was readiness in the Russian-speaking audience to watch it. But as the riots faded, funding to get the project off the ground faltered and the opportunity to tie Russian speakers into ERR was missed. The country’s then prime minister Andrus Ansip said it was too difficult to compete with Russian TV channels so ERR’s Russian-language offerings would be limited to radio.

ETV+ is dancing on the razor’s edge. If it covers politics too much it will raise the ire of politicians who could cut its funding. Too much pro-government propaganda could turn off the Russian-speaking audience. Lurking in the background are ratings challenges that could force it to air infotainment and entertainment programmes.

As ETV+ turns two months old, it remains to be seen how it will develop. But connecting with Estonia’s Russian-speaking citizens must be its first goal.

This article was originally posted at indexoncensorship.org

This article was updated on 5/1/16 to clarify ETV+’s viewership numbers.

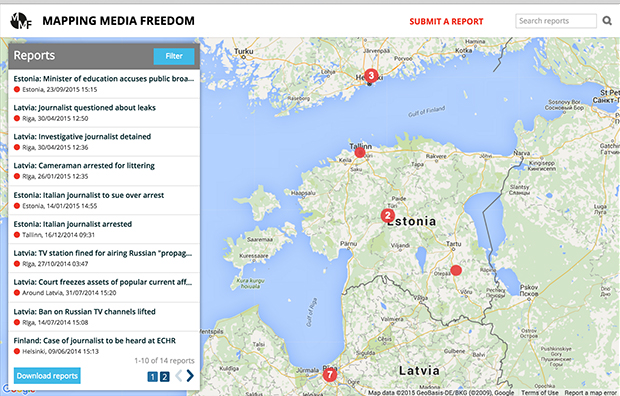

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

15 Dec 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, Germany, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News

Pressure is mounting on journalists in Germany from right-wing groups that intimidate, insult and sometimes physically assault them, according to an analysis of reports filed to Index on Censorship’s project Mapping Media Freedom. In 2015 there were 29 attacks on media in Germany, 12 of those incidents were connected with the far right.

Starting in autumn 2014, the anti-immigrant, right-wing extremist group PEGIDA (Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamisation of the Occident) began as a protest movement that a year later still holds large demonstrations in cities around the country. PEGIDA, along with the populist right-wing political party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) and similar extremist splinter groups frequently hold rallies that have become sites of aggression and violence against journalists reporting on them.

In 2014, Germany’s annual prize for Un-word of the Year for the most offensive new or recently popularised term went to “Lügenpresse” (lying press), a motto chanted at protests to smear journalists. Angry demonstrators call journalists part of a biased political elite. When journalists try to interview rally participants, they’re often turned away, yelled at or attacked.

“Index is extremely disturbed by the continuous attacks on journalists by right-wing protesters in Germany,” said Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project officer, Hannah Machlin. “Media workers have been repeatedly assaulted and insulted in their line of work and these aggressions must be addressed by public officials in order to preserve press freedom in the country.”

Below are five recent stand-out cases of right-wing extremist intimidation of journalists.

1. “Left-wing pig” attacked

On 30 October, Helmut Schümann, a columnist for the Berlin daily newspaper Tagesspiegel, was attacked by several assailants in front of his apartment building in the city’s Charlottenburg neighbourhood. An attacker asked “Are you Schümann for Tagesspiegel?” and then called him a “left-wing pig”.

On the day before the assault, Schümann had published an article about the rise in xenophobia coming out of right-wing extremist groups, headlined: Is that still our country?

Schümann filed a complaint of physical assault and insult with Berlin police. Following the attack, he said: “I’ll keep running my column, positioning myself and won’t let myself be intimidated.”

2. PEGIDA’s anniversary celebrated true to form

At a PEGIDA rally in Dresden on 19 October, several journalists were physically attacked. The demonstration was held to mark the one-year anniversary of the protest group and attracted thousands of people.

A reporter for German international broadcaster Deutsche Welle, Jaafar Abdul Karim, was surrounded by protestors while filming with his crew. He was prevented from filming and called a racial slur before being hit in the neck. His attacker ran away.

Jose Sequeira, a cameraman for the Russian TV channel Ruptly, had his gear thrown to the ground by protesters. He was then beaten in the back and head by a group of six or seven men.

At the same protest, an employee of German public radio station Deutschlandradio was attacked by a drunk protestor and mildly injured.

3. Belittling the “lying press”

Right-wing attacks against media workers include insults, intimidation and physical attacks

On 3 September, the offices of the newspaper Bad Hersfelder Zeitung in central Germany were graffitied with disparaging comments about the paper’s coverage of asylum seekers. The graffitied comments read “stop asylum craziness”, “no Islam” and, lo and behold, “lying press”.

The newspaper had been covering conditions in reception centres for asylum seekers before the vandalism.

On 15 November, another newspaper in the small eastern German city of Glauchau was attacked by at least one man seen throwing six rocks through the Freie Presse‘s office windows.

Police did not immediately identify a right-wing motive behind the assault while they looked for suspects.

4. Physical assault on cameraman

Aggressive protesters at another large PEGIDA rally on 23 November physically assaulted a cameraman who was filming the protest with a Russian TV crew. The 43-year-old suffered non-serious injuries and was brought to a nearby hospital.

Police arrested one 28-year-old suspect in connection to the attack.

5. Reporters punched and kicked at Dresden rally

Dresden, where PEGIDA began, was host to several shameful attacks against journalists in 2015. On 28 September, one reporter from state public broadcaster Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk (MDR) was kicked and another from the newspaper Dresdner Neueste Nachrichten was punched in the face while covering a large rally organised by the extremist group.

The MDR broadcast journalist reported after the assault that he was standing with colleagues adjusting his camera when he was approached from behind by a protester. When the journalists ignored the man’s questions, several other demonstrators joined in and began attacked the reporter.

Other protesters tried to grab the camera out of the hands of the Dresdner Neueste Nachrichten reporter and then punched him in the face.

As with many of the assault cases reported from protests this year, the assailants managed to escape into the crowd before police appeared at the scene.

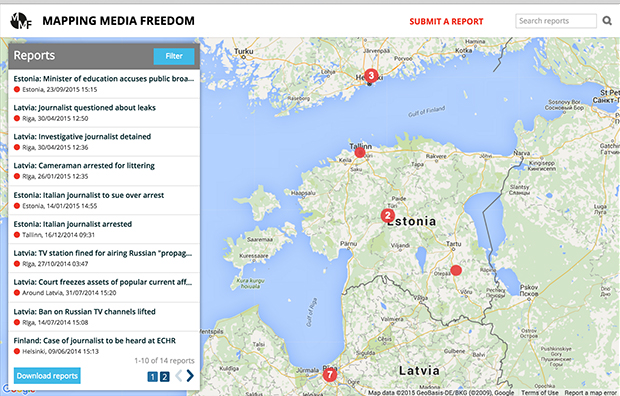

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

11 Dec 2015 | Italy, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News

For weeks, Rome has been transfixed by the spectacle of the “Capital Mafia” trial, which began on 5 November. The prosecutors are laying bare an alleged network of corrupt relationships between politicians and criminal syndicates in the city. The scandal involves the misappropriation of funding that was destined for city services, according to prosecutors.

But the biggest surprise wasn’t in that “Captial Mafia” courtroom, it was at the district attorney’s office where a complaint filed by the criminal lawyers association denounced 97 journalists for violating the secrecy of investigations, which is a crime under article 114 of the country’s code of criminal procedure. Italy’s foremost and well-respected crime and courts reporters, as well as 24 chief editors, also stand accused of breaching the ethical norms of their profession.

The accusations against the journalists and editors stem from two waves of arrests — December 2014 and June 2015 — of defendants in the “Captial Mafia” trial. The coverage of the arrests and subsequent investigations generated 278 articles across 14 Italian newspapers. The published reports included details gleaned from arrest warrants of 81 people, including politicians, public administrators and alleged members of the mafia. The contents of the warrants were known to the police, prosecutors, the accused and their lawyers, but still formally subject to publication limits until the conclusion of investigations.

The lawyers that made the accusations believe that the journalists should have rigidly respected the limits and that the facts should not have been reported even if they were known to the parties involved.

Supporters of the journalists maintain that the case is too important and that it is vital for newspapers and journalists to inform Italians as fully as possible, especially in connection with a scandal of such vast proportions. Some see it as a form of legal intimidation that cannot be punished and a move to force the case against the defendants to be dismissed in the public mind as a journalistic fiction.

“We are facing a clear attempt to muzzle the press and the journalists. The journalists denounced have reported news that were not covered by the code,” Raffaele Lorusso, general secretary of National Federation of the Italian Press (FNSI), told Index on Censorship. “It is as if these lawyers want to tell to journalists: “Do not write more news concerning our direct beneficiaries otherwise you will be sued.”

One of the defendant’s lawyers denigrated Lirio Abbate, an investigative journalist and 2015 Index on Censorship Journalism Award nominee, who reported mafia activities. For his trouble, Abbate lives under 24-hour police protection due to death threats.

Currently, the decision to pursue charges against the journalists rests with the Court of Rome. Those involved could potentially face trial and a disciplinary penalty.

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

7 Dec 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News, Russia

Russia’s takeover of Crimea has been accompanied by an ongoing process that is shrinking the space for media and freedom of speech on the peninsula. As the clampdown progressed, a majority of the independent journalists either left the disputed territory or stopped openly criticising Russian policy. At the same time, the number of alternative sources of information declined significantly.

Russian and Crimean authorities have used red tape, paramilitary violence and threats to silence independent voices and media. They have stifled freedom of information and jeopardised journalist safety.

Journalists and media professionals dubbed Crimea “fear peninsula”.

Curtailing broadcast TV

As Russia took over, television stations opposed to the annexation were one of the first targets. In March 2014, Chornomorska, the largest local TV and radio company, and all Ukrainian stations had their analogue broadcasts terminated. This was followed two months later, in June 2014, by the dropping of Ukrainian cable TV channels in some cable networks.

Applying Russia’s extremism law in Crimea

Soon after the annexation, Russia began implementing its overly broad and vague 2002 law, On Countering Extremist Activity, which led to a surge in warnings against the media. In summer 2014, Shevket Kaybullaev, the editor-in-chief of the Crimean Tatar newspaper Avdet , was summoned to the office of public prosecution in Simferopol. Kaybullaev was interrogated because of a complaint against the paper that challenged coverage of the mood of the Tatar community in the run-up to local elections. The complainant accused the paper of “radicalism and extremism”.

Verbal accusations against journalists have also become day-to-day practice. The Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) and prosecutor’s offices demanded the removal of “extremist materials” from media outlets. Crimean Tatar TV channel ATR received two warnings about the “violation of legislation aimed at countering extremist activity”. The station management was reminded that the formation of an anti-Russian public opinion could be considered a violation of the extremist law.

Criminal penalties for “incitement to separatism”

On 9 May 2014, amendments were made to Russia’s Criminal Code. A new article, 280.1, states that “public calls for action aimed at violating the territorial integrity of the Russian Federation” is punishable by up to five years imprisonment. The words “annexation” and “occupation” are de facto banned in Crimea when referring to recent events.

The amended code has been used to target Crimean journalists. In March 2015, two journalists, the Center for Investigative Journalism’s Anna Andrievska and Natalia Kokorina, had their apartments searched. Kokorina was interrogated for six hours. The FSB opened the criminal case against Andrievska on charges of “incitement to separatism” based on her reporting on individuals providing support for the Crimea volunteer battalion fighting in Donbas, in eastern Ukraine.

Searches and seizure of property

Russian authorities are using searches and property seizure as a way to intimidate and pressurise media companies. In August 2014, the work of Chornomorska TV and Radio Company and the Center for Investigative Journalism were blocked after the seizure of their broadcasting equipment. The broadcaster wasn’t able to retrieve its equipment until five months later.

In September 2014, a search was conducted at the office of the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People, a representative body for the ethnic group. Because it shares the building with the Mejlis, the offices of the Avdet newspaper were also raided. Following the probe, the paper was ordered to vacate its offices within 24 hours.

In January 2015, a search was carried out at the ATR TV channel, which disrupted the station’s broadcasts and prevented newsroom staffers from reporting.

Using paramilitaries to put pressure on journalists

Paramilitary groups have also been used to target journalists. So-called Crimean self-defense groups have been found to have illegally detained, assaulted and tortured journalists, as well as confiscations of and damage to property. From 15 to 19 May, 2014, ten cases of journalists’ rights violations were recorded and documented by the Crimea Field Mission on Human Rights. The situation has been worsened by the fact that to date not all the documented attacks on journalists by self-defense group members have been investigated by Crimean authorities. This has created an atmosphere of fear and impunity.

Problems with registration and re-registration of Crimean media

After the Russian annexation, Crimean authorities demanded that all active media outlets re-register according to Russian legislation. As a result, mass media that was considered disloyal — including News Agency QHA and TV Channel ATR, among others — did not receive legal permission to continue their work on the peninsula. In February 2015, all Crimean independent radio companies were silenced after losing their frequencies during a bidding process that was carried out opaquely. Beginning on 1 April 2015, the Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information Technologies and Mass Communications (Roskomnadzor) stopped recognising Crimean media outlets with Ukrainian registrations, making their work in the annexed territory illegal.

Making media accreditation more difficult

New rules for accreditation in Crimea make it possible to selectively restrict media access to the authorities. The State Council of the Republic of Crimea issued new regulations that make “biased coverage” one of the reasons journalists could lose accreditation. Kerch City Council, for instance, prohibits journalists without accreditation from even entering the city hall.

Blocking access to the online media

In October 2015, media freedom in Crimea came under renewed pressure when websites were blocked. Roskomnadzor carried out a request by the general prosecutor to restrict access to the Center for Investigative Journalism and Events Crimea websites in Crimea and Russia. Roskomnadzor said that the information on the sites “contains calls for riots, realisation of extremist activity and/or participation in mass (public) events held in violation of the established order”.

These internet media outlets became the first Crimean mass media whose content are officially blocked on the territory of Crimean peninsula.

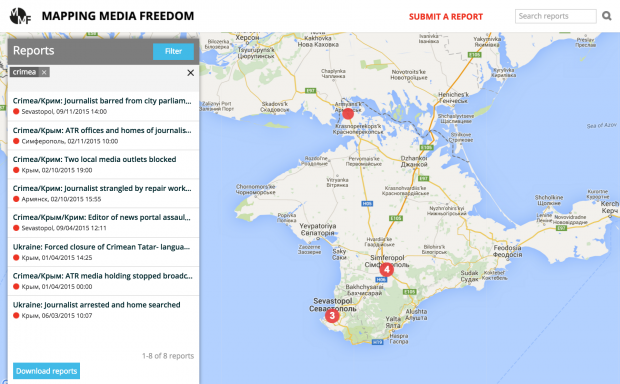

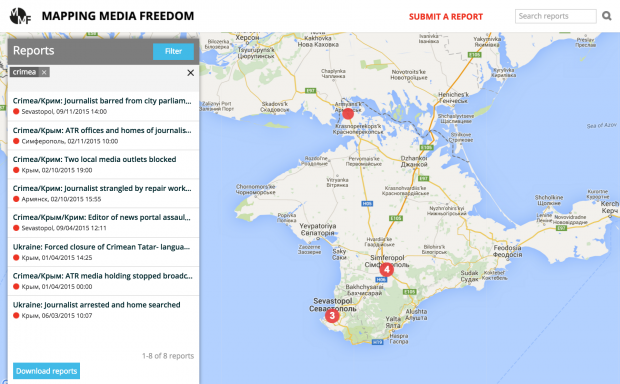

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|