3 Dec 2015 | Belgium, Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News

Following the murderous barbarism in France last month, a state of alert was subsequently declared in Belgium amid concerns that a “Paris-style” attack was imminent in Brussels. The city went into lockdown for five days, the army was deployed on the streets, and the authorities asked the media and public not to report on what was happening.

Belgian media complied, as did Belgian Twitter users, who, under the hashtag #BrusselsLockdown, posted pictures of cats rather than comment on police raids.

The lockdown of Brussels has certainly raised some important questions. As Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project shows, it may indicative of a wider problem of media violations within the country.

1. Prime Minister’s office threatens journalist

During the visit of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Tristan Godaert, a journalist working for RTBF, the public broadcasting organisation of the French community of Belgium, was repeatedly threatened by the press secretary and the spokesperson of the Belgian Prime Minister Charles Michel while covering the visit of Turkish President Erdogan. On 6 October, during a speech by the Turkish president, Godaert shouted: “Mr. Erdoğan, why is Mohammed Rasool still in prison in Turkey?” A Turkish embassy official then a representative of the Belgian government who then informed RTBF that they were no longer allowed to film. Afterward, the Belgian Prime Minister’s communications director threatened the journalists, saying that if the footage was aired there would be “consequences”.

2. Journalists arrested and forced to delete images during protest

On 15 October, around 100 people were arrested in Brussels at a mass demonstration against TTIP (Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership), an impending free trade deal between the US and the EU.

During the protest, Thomas Michel, a freelance journalists working for Zin TV, and Maxime Lehoux, an Italian photojournalist, were arrested by the Belgian police and forced to delete photographs they had taken.

A press release by Zin TV following the incident said: “The images contain the humiliation of the police inflicted on protesters […] We remind that it is illegal to be seized from its sources, it is a violation of professional secrecy and the level of justification 3 of 4 on the scale of the risk of terrorism is simply bogus.”

3. Turkish reporter assaulted at polling station

R Doğan, a Cihan news agency reporter, was physically and verbally assaulted on 19 October by a polling clerk at a voting station in Turkey’s Consulate General in Brussels for the Turkish Justice and Development Party (AKP).

Doğan was insulted by the AKP clerk, who grabbed his arm and escorted him out of the building. The reporter was there to observe Turkish citizens based abroad who were voting as part of the 1 November Turkish general election.

4. Palestinian journalist assaulted during Brussels Muslim Fair

On 7 November, Palestinian journalist Salama Attaallah was assaulted while covering the annual Muslim Fair activities in Brussels for Al Ghad TV. While shooting, an individual introducing himself as a representative of Al Aqsaa demanded he stop filming women participating to the fair. Attaallah refused, explaining that he was not there to film women, but rather to report about the event in general. As a result, he was punched repeatedly in the face. The whole altercation was caught on film.

5. Médor investigative magazine censored by the judiciary

Médor a new investigative magazine in Belgium, has been censored by the Belgian judiciary at the request of a businessman representing a pharmaceutical company.

In its first issue, Médor published a story about the financial structure of the pharmaceutical company that is largely supported by regional authorities. The investigation, which lasted more than six months and compiled extensive documentation, was conducted by the award-winning David Leloup.

The Association of Professional Journalists, an EFJ-IFJ affiliate, has expressed its shock at the censorship and offered legal support to Leloup.

6. Russian NTV channel journalists assaulted and robbed

On 18 November, NTV channel reporter Konstantin Panushkin and cameraman Zakir Ansarov were beaten and robbed in northern Brussels. The Russia-based journalists were seeking to speak with relatives and friends of a jihadist-related to attacks in Paris.

Panushkin said that they were interviewing a group of 10 teenagers, when both were assaulted and robbed. The assailants took a backpack with documents, money and a laptop.

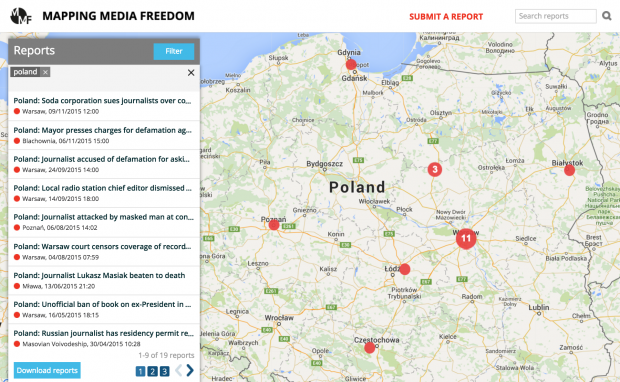

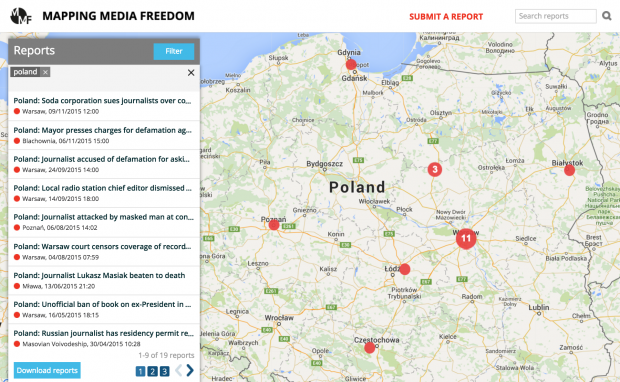

Details of attacks on the media across Europe can be found at Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom website. Reports to the map are crowdsourced and then fact-checked by the Index team.

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

1 Dec 2015 | Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News, Poland

Fact-checking is crucial for any piece of journalism. This was what the investigative journalist Jaroslaw Jakimczyk set out to do when he wrote an email to the press office at IT and technology company Qumak S.A. requesting authentication of information he had.

The company, which is based in Warsaw, provides information and communication services to well-known clients, such as the major Polish bank Pekao. Jakimczyk’s questions pertained to discs of private client data that, according to his information, there was proof of a transaction of sale between the two parties. When Jakimczyk received a response from Qumak’s press office in late September, the denial of any wrongdoing on their part was followed swiftly by something rather unexpected: Qumak was now pressing charges against Jakimczyk for defamation under article 212 of the Polish penal code.

Under article 212 of the Polish penal code, defamation is when one person defames another individual, group, company or association, over such characteristics “that might lower it in the public opinion or contribute to the loss of trust which is required for the office executed by it”. Defamation can be subject to up to a year’s imprisonment if “done through means of mass communication” under paragraph 2; without mass communication, one might just get away with a fine or, rather vaguely “limitations to freedom”. Until amendments were made to the law in 2010, imprisonment was a general possibility. A public apology is usually also a popular demand with any article 212 claim.

Defamation charges appear to have been keeping Polish judges increasingly busy over the years: The Helsinki Foundation of Human Rights, in its publication on article 212, points out that while 43 article 212 claims were put forward in 2000, by 2011, this figure had risen to 232. At times, the entire Polish judicial system is exhausted. This happened to Andrzej Marek in 2004, who had accused a local politician of corruption in an article, and Marian Maciejewski, who had written articles critical of judicial inaccuracies in the city of Wroclaw.

In both instances, defamation charges were pressed, and both cases took years to reach the European Court of Human Rights to be ruled breaches of article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which deals with free expression. The court ordered compensation payments for the journalists. Five more very similar cases were rejected by European Convention in the same way. But article 212 claims continue to dog journalists.

A part in the explanation for the increase of claims lies, for multiple reasons, with the internet. As Dorota Glowacka, an expert on 212 at the Helsinki Human Rights Foundation, told Index on Censorship, the fact that information is online might instill a heightened sense of urgency in potential claimants, as “the statements would be perceived as more harmful to their reputation, due to them remaining ‘online forever’”. Paradoxically, the accessibility of information through the web, according to Jakimczyk, might also work against them: “Many representatives of local oligarchies who read and analyse online publications on the subject have come to the somewhat correct conclusion that there are means to silence uncomfortable journalists.”

A review of cases of journalists charged with article 212 shows that local authorities are often involved. Earlier this month, the mayor of the small municipality in south-east Poland, Blachownia, decided to press charges against the editor-in-chief of a critical independent local news portal. As Jakimczyk noted, “previously, many of those based in Polish provinces had not heard of such a possibility or did not have enough courage to go ahead with them”, but the “amplification of cases charged with article 212 might have encouraged them to take up the same”.

In fact, council authorities sometimes press charges under 212 on behalf of a criticised local politician, arguing that such criticism “hits the good reputation of the whole council”, as Glowacka said. Such cases are rather comfortable arrangements for the politicians, as it involves no expenditures or extra efforts of their own: they can make use of the council’s legal services, and any costs relating to the case will be paid for.

Glowacka said that the cases reaching the attention of the Helsinki Human Rights Foundation have still largely been those of journalists and political activists. Increasingly, though, even the average citizen leaving a negative product or brand review, might get sued for defamation. And if comments are left anonymously, then article 212, as part of the criminal code, guarantees police support in subject identification; if one were to consider taking up the alternative route through the civilian code that also protects personal goods and good reputation, this possibility does not exist.

Attempts to strike the article from the criminal code have come from many angles over the years: between 2007 and 2012, the OSCE, the Council of Europe, as well as freedom of speech and human rights delegates of the UN openly criticised the article for curtailing freedom of speech. The diplomat Irina Lipowicz had challenged the possibility of imprisonment for defamation before the Polish Constitutional court three years ago, but that only pointed to its 2006-ruling, when it was decided article 212 did not infringe upon freedom of speech.

In 2011, the Polish citizen Mariusz S. filed a petition to remove 212 from the Polish criminal code, but the voting did not bring about a clear majority and the provision remained in place. The Helsinki Human Rights Foundation, in the run-up to the 2011 national parliamentary elections, promoted a large-scale campaign to ‘Erase article 212’. At the time, 140 Polish MPs declared they would support a move to drop the defamation clause.

It appears, though, that there is a lack of substantial, genuine political will, and that, too often, it presents itself as a handy “whip” or looming “sword of Damocles”, Glowacka and Jakimczyk said. The former points to an illustrative example of the Polish People’s Party [org.: Polskie Stronnictwo Ludowe], which officially backed the Erase initiative in 2011, only for its vice chair Eugeniusz Grzeszczak to put forward claims against journalists in his constituency a year later, when he disagreed with their revealing his payments to a favourable publisher. For Polish politicians to truly find interest in removing the provision, “an incident would be needed of accusations on article 212 pressed against a representative of this very class, which appears to consider itself as a club of untouchables”, Jakimczyck commented.

The journalist underscored another, deeper issue that the threat of defamation charges makes possible. The ties between business and media publishers are close to the extent that they lead to “the introduction of unwritten rules, limiting or excluding publication of critical material on certain companies, corporations or public institutions, which have a large advertising budget to their disposal.” It does not seem a coincidence that critical material has been increasingly held back, especially since the financial crisis in 2008, he said.

In Jakimczyck’s experience, this has pertained to any reports on firms which the state treasury has shares in, including major names such as the largest Polish insurance firm PZU, the copper and silver production company KGHM Polska Miedz, the Polish oil refiner and retailer Orlen, as well as the Polish Energy Group. Every time an article remained unpublished, “never did those responsible [at the paper in question] provide a satisfactory justification as to why publication was denied”. The incident with Qumak’s charges, tied budget-wise to the largest Polish bank, is no longer an isolated incident so much as “the further logical consequence of the new phenomenon that is preventive censorship”. Worryingly, these are not publicly accountable institutions but rather in the hand of “private capital that is not subject to societal checks and balances”.

Jakimczyk’s case, in the meantime, appears resolved: in a court ruling earlier this month, judges found that to qualify for defamation, the content in question has to have at least been shared with one other person; judges have also raised the crucial point that a journalist’s main role is to ask questions, i.e.: the journalist was just doing his job. Qumak S.A. will now have to cover any resulting fees for courts.

Although the company is legally entitled to claim revision, for the sake of the state of journalism in Poland, it is hoped that this case will remain at that, and set an ultimate example what worrying direction alleged defamation charges should stop going to in Poland.

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

27 Nov 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, France, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News

Editorial Credit: Frederic Legrand – COMEO / Shutterstock.com

Even before the attacks on Paris on 13 November were over, French President Francois Hollande declared a nationwide state of emergency giving authorities additional powers in the name of protecting citizens and combatting terrorism. But since the attacks, concerns have been raised for press freedom prompted by the cancellation of a regular radio segment by journalist Thomas Guénolé.

A few days after the events of 13 November, Guénolé devoted his daily morning commentary piece on RMC radio to what he perceived as the failings of the French security services and police. On the same day, the Interior Ministry called Philippe Antoine, RMC managing editor, to demand the radio station air a corrective to points Guénolé discussed during his segment, which the ministry would pen. “Interestingly, the corrective was not going to appear as a corrective emanating from the Interior Ministry but as the correction of an inaccurate information emanating from RMC,” Guénolé told me.

The proposed corrections were in relation to Guénolé’s discussion of claims reported by various news outlets, including that France had known since August 2015 that IS planned to attack a rock concert in France and that Turkish authorities had warned France twice this year about Omar Ismaïl Mostefaï, one of the assailants of the Bataclan massacre.

Guénolé called for a parliamentary investigation which should, if these claims were true, prompt the resignation of the highest ranking French officials, including Bernard Cazeneuve, France’s Minister of the Interior.

Guénolé also repeated information published by La Lettre A, which claimed only three out of 50 members of the Parisian Brigade de recherche et d’intervention (an anti-gang unit, which is to intervene in hostage situations) had been on duty after 8pm on the night of the attacks. On 19 November, the special adviser to France’s interior minister, Marie-Emmanuelle Assidon, took to Twitter to say the information contained in La Lettre A was false but recognised she had not read the article. “[N]o one but Thomas Guénolé trusts your info,” she added in her tweet.

“I have repeatedly asked Place Beauvau for a denial,” Marion Deye, editor at La Lettre A, told me. “I haven’t had one.” Neither have Le Monde or the AFP, also quoted by Guénolé.

“We published a very factual piece of news on the Monday following the attacks, at a time when any type of criticism was not welcome,” Daye said. “However, what we published was not a criticism, just a report. The most absurd thing in this whole story is that no one knows what Place Beauvau denied when they spoke to RMC. I think what was really problematic for some was that Guénolé brought up the resignation of Cazeneuve.”

On Friday 20 November, Guénolé was informed that his daily column was cancelled. In an email, the RMC managing editor wrote: “The Interior Ministry and all the police services invited on air have refused to appear on RMC because of inaccuracies in your column. Most sources of our police specialists have gone silent since Tuesday, putting in jeopardy the work that our editorial team does to find and verify information.”

Guénolé described the actions against him as both a “boycott” and an “embargo”.

“One would expect a media outlet to back up its journalist and not to have too strong a dependency vis-à-vis institutions,” he said. “My particular case doesn’t matter so much. What is unacceptable is that the Interior Ministry seems to have pressured RMC because they were displeased with what a journalist said on air in the context of the state of emergency.”

The firing of Guénolé happened on the on the same day the Assemblée Nationale voted to extend the state of emergency from 12 days to three months. Measures to control the press were initially proposed by 20 socialist MPs led by Sandrine Mazetier on the basis that the coverage of the January 2015 attacks in Paris – especially by news channel BFM-TV – had endangered the life of hostages who were hiding in a Hyper Casher supermarket. Such a measure would be highly problematic. As Mathieu Magnaudeix, a journalist with the investigative website Mediapart, put it to me: “If we were to end up with an authoritarian power, which by now doesn’t seem to be out of the question, what could they do with a law that allows the control of the press?”

Thankfully, the press control measures were later dismissed and it was made clear that even Hollande was strongly opposed. Regardless, it is apparent journalists still aren’t safe.

The proposed law does, however, extend and harden house arrests that are allowed under a state of emergency, enables members of the police force to carry their weapons while off duty, gives stronger powers to the authorities to carry police searches that are not approved by a judge. While these cannot be carried out in the workplace, police searches can take place at the house of an MP, lawyer, a judge or a journalist.

This kind of anti-terror legislation, as we have seen in the UK, could have further negative consequences for journalists covering terrorism.

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

26 Nov 2015 | Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News

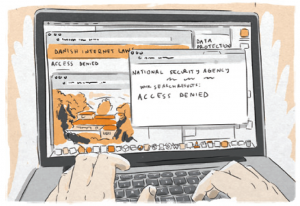

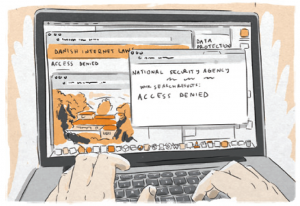

A new graphic novel exploring challenges to press freedom across Europe and the impact of limitations on journalists has been released by the European Youth Press.

A new graphic novel exploring challenges to press freedom across Europe and the impact of limitations on journalists has been released by the European Youth Press.

Free Our Media is the result of a collaborative effort over the course of several months by a team of young journalists and illustrators assembled from all over Europe by European Youth Press, and contains 14 comics, each story centred on the state of media freedom in a different country. The project was funded by the Council of Europe.

Planning for Free Our Media started in autumn of 2014, when the European Youth Press team began outlining which media advocacy issues the organisation would focus on in 2015. Press freedom was high on the list of priorities, given its recent deterioration in the EU and neighbouring countries, and the organisation’s resolve to tackle this particular issue was only heightened by the violent attacks on satirical French newspaper Charlie Hebdo in January 2015. The visual medium of the graphic novel was chosen in order to make the content more universal across borders and language barriers.

“A written article would get shared by an audience that is already familiar with the topic of press freedom,” said European Youth Press board member and Free Our Media project coordinator Anna Saraste. “In the comic book, we communicate the topic with a visual medium that appeals to a broader public.”

“A written article would get shared by an audience that is already familiar with the topic of press freedom,” said European Youth Press board member and Free Our Media project coordinator Anna Saraste. “In the comic book, we communicate the topic with a visual medium that appeals to a broader public.”

Creating the graphic novel was a challenge from start to finish, not least because of the distance between the participants. The journalists, who are aged between 18 and 35 and collectively dubbed Media Freedom Ambassadors, met twice before the final workshop. During these events, the group developed tools for actively addressing limitations to press freedom. They also had the opportunity to organise events within their own communities, which allowed them to gather input from other journalists and young media makers about press freedom and its value in society.

Months of work culminated in Berlin in July 2015. During a five-day workshop led by artists Yorgos Konstantinou and Marcos Mazzoni, the group of journalists met with the cartoonists and, in pairs, planned the storylines for each comic. Following the end of the workshop, the group worked on their pieces separately, and kept each other updated on their progress via Facebook and Skype, said Jo Breese, a British illustrator and Sunday Times graphic artist who was selected as one of the cartoonists for Free Our Media.

“You can draw silly cartoons about serious matters, and it helps, and it gets the message across,” Breese said. “And I think that was important for a lot of the people who were there, whose countries don’t have very good press freedom. It gave them a platform to say what they wanted to say.”

The book’s varied stories and illustration styles made the creation of a cohesive graphic novel another significant challenge. The solution devised by the team was a common color scheme throughout, comprised of various shades of white, black, and orange.

The completed graphic novel was officially released at the European Youth Media Days that took place in the European Parliament in Brussels from 20-22 October. Because the European Youth Press is a non-profit organisation, they must rely on donations to print, but soon hope to be able to start selling copies of the book online. While the book itself is a valuable tool for combating limitations on press freedom in Europe, Saraste is quick to emphasise that the real agents of change are young media makers.

“I wouldn’t focus so much on the book. I think what will be impacted for a long time are the ambassadors,” she said. “I think a lot has changed for them in terms of how they see their role as young media makers. Something in their attitude changed. They will have an impact on other people, wherever they go and wherever they decide to practice this profession.”

Following the completion of Free Our Media, the Media Freedom Ambassadors are continuing their activism by blogging for Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project, to which they will contribute reports about their own countries and act as references for the site.

You can preview the graphic novel here.

This article was published on 26 November 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

A new graphic novel exploring challenges to press freedom across Europe and the impact of limitations on journalists has been released by the

A new graphic novel exploring challenges to press freedom across Europe and the impact of limitations on journalists has been released by the  “A written article would get shared by an audience that is already familiar with the topic of press freedom,” said European Youth Press board member and Free Our Media project coordinator Anna Saraste. “In the comic book, we communicate the topic with a visual medium that appeals to a broader public.”

“A written article would get shared by an audience that is already familiar with the topic of press freedom,” said European Youth Press board member and Free Our Media project coordinator Anna Saraste. “In the comic book, we communicate the topic with a visual medium that appeals to a broader public.”