24 Jun 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, News, Poland

Journalist Lukasz Masiak, founder of news site NaszaMlawa.pl, was attacked and killed in Poland on 14 June 2015. Masiak, who had been subject to numerous threats believed to be connected to his work, died of traumatic brain injury after being assaulted, according to TVN24.

Launched in 2010, NaszaMlawa.pl covers Mlawa, a town of about 30,000 in the north central part of Poland. Masiak’s site reported on several controversial issues, including the dealings of local businessmen, drug use involving participants of the local mixed martial arts league, incidents involving Roma citizens in the area and the botched investigation into the death of a young woman. He received death threats following the latter story.

The attack on 31-year-old Masiak took place in the bathroom of a local establishment at about 2am on 14 June. Police have issued an international arrest warrant for Bartosz Nowicki, a 29-year-old mixed martial arts fighter. Two people who were earlier detained have now been released. Police consider them witnesses to the incident.

Masiak had previously received threats over the phone and through the mail, local media reported. In December 2014, he was sent his own obituary. In January 2014, he was the victim of a physical assault in near his home, in which he said he had also been tear gassed.

“It certainly was not a robbery.” Masiak said at the time. “It was a person who was waiting for me. For sure it was about posting reports on the portal.”

Though the journalist had reported incidents to the police, there had been no arrests by the time of his murder.

Alicja Śledziona, police spokesperson for the region of Mazowieckie, said that the department had received two complaints from the journalist. Masiak had told the department that the January and December 2014 incidents could have been related to his reporting, including one about a traffic accident. She said both cases were treated very seriously, but investigators were unable to tie the incidents to individuals.

The killing has been met with widespread condemnation from press unions and media freedom organisations.

“Media workers in Europe are facing an increased level of violence as they do their jobs. We call on the European Union and governments across the continent to mount a concerted effort to protect press freedom and the lives of media workers by aggressively pursuing threats of violence against journalists,” said Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg.

“Index has been tracking threats to journalists across Europe for more than a year, through our Mapping Media Freedom project, and have noted a worrying trend of violence towards the sector. Around the world, there have been 54 murders of journalists so far this year. It shouldn’t have to take another death to make protecting journalists a priority at the highest levels of government,” Ginsberg added.

The crime was condemned by the Press Freedom Monitoring Centre of the Association of Polish Journalists. The body wrote to Polish Interior Minister Teresy Piotrowskiej, criticising the failure of state authorities to provide him with “elementary security”.

Mogens Blicher Bjerregård, president of the European Federation of Journalists, shared his organisation’s condolences with Masiak’s family and demanded an “effective investigation in order to find and prosecute the responsible perpetrators for this horrible crime”. EFJ, along with Reporters Without Borders, is partnered with Index on the Mapping Media Freedom project.

Dunja Mijatović, the OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media, strongly condemned the killing and expressed her condolences to Masiak’s family and colleagues. “This is a tragedy and a horrific reminder of the dangers journalists face around the world,” Mijatović said. “Journalists are increasingly targeted because of their profession and what they say and write, and this trend has to stop.”

27 Mar 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News, Serbia

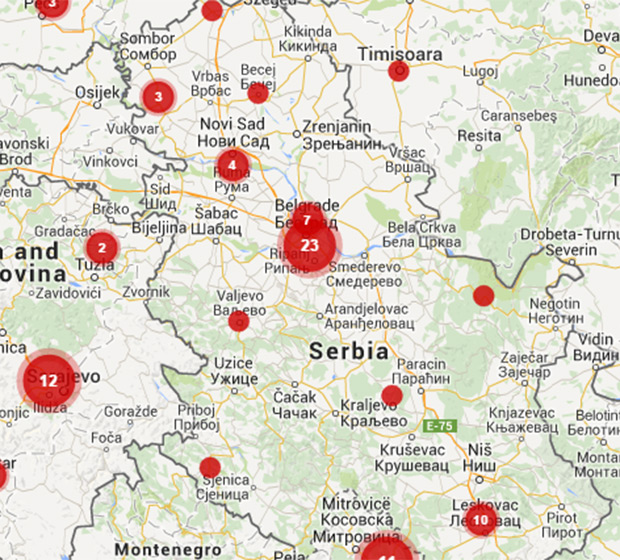

Working as a professional journalist in Serbia is hard. Being one in the country’s inland is even harder. Out of the 58 verified incidents involving Serbian media outlets and professionals reported to Index on Censorship’s European Union-funded Mapping Media Freedom, 30 have occurred outside Belgrade; the country’s political, economic and media capital. Four of these incidents have been directed at Juzne Vesti staff.

Launched in 2010 by journalist Predrag Blagojevic, Juzne Vesti is an independent news site based in Nis, a town of 257.000 in southern Serbia. In just over five years, its journalists have been subjected to verbal harassment or death threats 15 times. Though they have reported the incidents to local authorities, it has not resulted in convictions.

“Nobody has been found guilty and punished for the threats,” Blagojevic, who is also the site’s editor-in-chief, told Index.

According to Blagojevic, the main obstacle to punishing those threatening journalists comes from the prosecutor’s office. While he is quick to complement police in the town for their professional and timely investigations, he blames prosecutors for failing to act on the evidence by filing indictments quickly.

“In two situations from four to six months passed from the time the police filed a criminal charge to the prosecutor’s indictments,” Blagojevic explained.

Juzne Vesti correspondent Dragan Marinkovic from Leskovac received threats on Facebook after he published an article about the death of a woman, in which he questioned the treatment provided by a paramedic. He reported the incident to authorities. Several months later prosecutors decided not to pursue the case, arguing that “you deserve a bullet” is not a threat.

In March 2014 Blagojevic was threatened by the owner of a local football club, yet prosecutors waited until late September to indict the main suspect. The first court hearing was scheduled for December 2014; the next one at the end of this month.

While such delays are frustrating, once in court, judges have taken some dubious positions, Blagojevic said. In one case, the court said that “be careful what you write” or “do not play with fire” were not threats, but words that “merely showed the seriousness of the topic”. In another instance, where the perpetrator asked a Juzne Vesti staffer “Will you be alive in the morning if you wrote something like this in the USA?”, the court said that “the inductee, by placing the action in the foreign country, shows that he is aware that murder is prohibited by Serbian law”.

Outside the legal system, there is another obstacle to independent journalism in Serbia: money. While the Serbian government pays for advertising space, most of the earmarked money is directed at the national press. At the same time, the number of successful companies outside Belgrade and Novi Sad are few, and those that do thrive in the Serbian inland are usually aligned with local political figures. That leaves a tiny pool of advertisers.

“In these circumstances we are left with only very small companies, which are connected with political parties or dependent on municipal budgets. The game is straightforward — only if you are good to us you will get money,” Blagojevic said.

In an interview with SEEMO, Blagojevic described situations where certain media outlets have been financed with taxpayers’ money. With this line of funding, competing outlets are able to offer low rates that distort the advertising market, which puts pressure on independent media to drop their rates.

“The local government in Nis sets aside hundreds of millions of dinars in payment for these PR services,” Blagojevic said. The money is sometimes up to 80 per cent of the budget for these outlets making it even more difficult for independent media to compete.

The Council of Europe’s recent report on the Serbian media situation addressed the issue: “Instead of making efforts to create non-discriminatory conditions for media industry development, the state is blatantly undermining free market competition.”

The last issue confronting Juzne Vesti staff is one that will be familiar to small town journalists around the world — everyone knows everyone. Blagojevic tells of having to convince one journalist to file a complaint because she knew the person who had targeted her. She was reluctant because she had known the person “since they were kids”, he said.

From Blagojevic’s point of view, the toxic mix of money, political pressure and indifference from the courts causes self-censorship among journalists.

“The language from the 90s is back in Serbia. Again, journalists that criticise the work of the government or are reporting on corruption are labelled as foreign mercenaries. Threats like this come from the mouths of the highest state representatives,” he said.

An earlier version of this article stated that Nis has a population of 184,000. The latest census puts the figure at 257.000.

This article was posted on March 27, 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

12 Jan 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, News, Serbia

Around 1 am on Thursday 3 July 2014, Davor Pasalic, editor of Serbian news agency FoNet, was brutally assaulted as he made his way home from the office. Pasalic, who had stopped for pizza, was accosted by three young men who demanded money and told him they had a gun. Pasalic refused and the men began beating him while shouting nationality-based slurs. Pasalic estimates that they struck him about 30 times before leaving him alone. The injured man then crossed a bridge leading to his apartment and was again attacked by the three men. The two attacks left him with cuts and bruises to his head and body. Four of his teeth were broken or knocked out.

“I have no clue why those three guys attacked me,” Pasalic told Index on Censorship. “One of the guys asked me: Are you a Croat? I was born in Belgrade. I have no accent. I look like every other citizen of Belgrade. Nobody has ever asked me that question before. How did he figure out that I am ethnic Croat?”

Six months have elapsed since the brutal assault, but police have made no progress in unmasking the culprits or discovering their motives. Nebojsa Stefanovic, Serbian minister of internal affairs, insists authorities are handling the incident as a priority, while Pasalic has said he is not certain whether police are unwilling or unable to resolve the assault. Journalists’ associations in Serbia are worried, vowing they “won’t allow” the beating to become just another case in the long line of unresolved attacks on media workers in Serbia.

From 2008 to 2014, Serbian has seen a total of 365 physical and verbal assaults, intimidations and attacks on property of media professionals, according to a report by the Independent Journalists’ Association of Serbia (NUNS). The numbers should be taken as provisional, it added, since many media workers do not report attacks. The real figure is likely higher than the official one. Since May 2014 alone, Index’s European Union-funded Mapping Media Freedom has received 48 reports of violations against Serbian media including attacks to property and intimidation and physical violence, one of which was the attack on Pasalic.

“In the period between 2008 and 2011 less than 10 per cent of all attacks were processed,” NUNS said. “We also have problems with the judicial process, even in cases where the identity of the aggressor is very obvious. In Serbian courts it is common for attackers to receive minimum sentences, which obviously encourages attacks,” said NUNS’ President Vukasin Obradovic in a statement. He believes this situation leads to self-censorship within the country’s press.

Media freedom violations are also covered in the annual reports on human rights in Serbia by the Belgrade Center for Human Rights (BCHR). In 2013 they reported, among other things, that hand grenades had been thrown at the home of the owner of the website Telegraf and that four journalists were under 24 hour police protection. In 2012 they pointed out, pointed out that despite a high number of attacks on the media, trials of press workers progressed faster than trials of perpetrators of attacks on journalists: “Minister Velimir Ilic was at long last found guilty and fined almost 1.4 million RSD for physically assaulting a journalist of the Novi Sad TV Apolo back in 2003. The assailant on TV B92 cameraman in 2008 was sentenced to one year in jail in 2012. The men who threatened to kill the author of the B92 show Insider Brankica Stankovic in 2009 were sentenced to 16 months’ imprisonment and six-month and one-year conditional sentences respectively.”

BCHR noted in its 2011 report that some court judgments confirmed the suspicion that perpetrators who attack journalists can count on lenient sentences. In 2010, they found that journalists were mostly being attacked by politicians, policemen and local businessmen dissatisfied with their reporting, and that — like in the previous years — most of the perpetrators went unpunished.

There are also cases where law enforcement authorities appear to simply not be doing their jobs, according to lawyer Kruna Savovic, who is part of the NUNS legal team. Speaking to Radio Free Europe, she shared the story of a journalist who reported death threats against him and his mother to the police. He stated the identity of the suspect, named witnesses and filed a report, but instead of processing the case, officers told him he would be charged if he continued to bother them.

The attacks on Pasalic were not captured by surveillance cameras in the area, and according to Stefanovic’s statement, the lack of video is complicating the investigation. The minister also asserted that a report was not filed on the night of the incident. Pasalic refutes that, saying he had sought medical treatment at the military medical academy after the assaults and told the on-duty officers what had occurred.

Serbian journalists’ associations have been unified in condemning the incident. “Serbian society is burdened with numerous attacks on journalists which remain unsolved and their perpetrators unpunished, sometimes for decades. This encourages the attackers and contributes to spreading fear and insecurity both among journalists and the society as a whole,” the Association of Independent Electronic Media (ANEM) pointed out.

The international community has also taken note. “Journalists’ safety is a key issue in the OSCE region. There must be no impunity for crimes committed against media workers”, said OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media Dunja Mijatovic, and in its 2014 progress report on Serbia, the European Commission stressed that threats and violence against journalists “still remain a concern”. The Commission and other international non-governmental organisations urged Serbian authorities to keep their promised to investigate the killings of journalists Radislava Dada Vulasinovic in 1994, Slavko Curuvija in 1999 and Milan Pantic in 2001, as well as other attacks.

So far a Serbian special commission, which was created in 2013 and tasked with reopening the unresolved murders of journalists has achieved progress in the case of Curuvija. The commission found information that connects four former state security officials with the killing. They were all charged. Three of them were imprisoned while “one of the indicted men is believed to be on the run and living in an African country”. In 2014, NUNS reported, there was only one journalist under 24 hour police protection.

After six months of investigation and zero progress Pasalic ironically says that his case is “no big deal.” But, he said that the assault has had no impact on his work.

Veteran B92 journalist Veran Matic has worked against impunity and to bring murders of Vulasinovic, Curuvija and Pantic to justice. “The culture of producing fear is the most efficient form of censorship,” he told Index last November. But he added: “In the same way as impunity restricts freedom of speech, solving of these cases, at least 20 years later, will surely contribute to journalists being encouraged to do their job in the best possible way.”

Recent reports from mediafreedom.ushahidi.com

Serbia: Prime minister calls BIRN’s journalists “liars”

Serbia: Journalist fired after demotion

Serbia: “Doctors” send death threats after report

Serbia: Mayor criticised for implying journalists not welcome

Serbia: Journalist demoted after publishing report

This article was posted on 12 January 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

15 Dec 2014 | News, Politics and Society, Turkey

On Sunday, December 14, at least 27 people were detained by Turkish police, including journalists, producers and directors of TV shows and police officers. Arrest warrants were issued for at least 31.

The offices of the newspaper Zaman and of the television network Samanyolu TV were raided by police. A warrant for the arrest of Zaman editor in chief Ekrem Dumanlı was at first incomplete, prompting police to return later on Sunday to arrest Dumanlı. Hidayet Karaca, manager of Samanyolu TV, was also detained, as well as Samanyolu producer Salih Asan and director Engin Koç, who were arrested in the city Eskişehir. Warrants were also issued for Makbule Çam Alemdağ, a writer for a Samanyolu show, and Nuh Gönültaş, a columnist for the newspaper Bugün. Bianet has published a list of those detained yesterday.

A large group of protesters gathered outside of Zaman’s Istanbul offices, holding signs that read “Free press cannot be silenced”.

Zaman and Samanyolu TV have been singled out by Turkish President Erdogan for being part of what Erdogan calls a “parallel structure” affiliated with exiled cleric Fethullah Gülen. Erdogan has accused Gülen of being at the centre of plots to topple the government.

The prosecutor in charge of Sunday’s operation said that those detained are being charged with involvement in a terrorist organisation, while some are accused of fraud and slander.

The raids were announced by the Twitter user “Fuat Avni” (a pseudonym) on December 13. Fuat Avni tweeted a list of 47 people for whom there would be arrest warrants.

On Monday Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan attacked the European Union for criticising the arrests that targeted opposition media outlets, telling the EU to “mind its own business.”

“The European Union cannot interfere in steps taken … within the rule of law against elements that threaten our national security,” Erdogan said in a televised speech. “They should mind their own business,” he added, in his first comments after Sunday’s raids.

EU foreign policy chief Federica Mogherini and enlargement commissioner Johannes Hahn on Sunday condemned police raids as going “against the European values” and said they were “incompatible with the freedom of media, which is a core principle of democracy.”

Recent media freedom violations from Turkey via mediafreedom.ushahidi.com:

EU project overshadowed by arbitrary media ban

BirGün newspaper to undergo investigation for critical coverage

Journalists assaulted, prevented from photographing

Economist and Taraf correspondent threatened on Twitter

Journalist sentenced to community service for insult

This article was updated on 15 December 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

This article was originally and updated at mediafreedom.ushahidi.com on 15 December 2014