2 Aug 2017 | Mapping Media Freedom, Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News and features

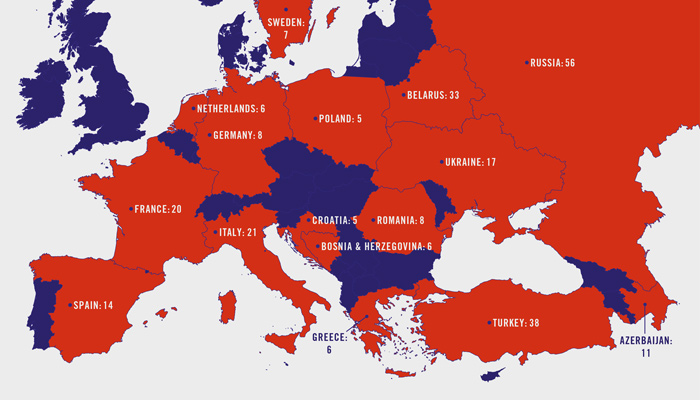

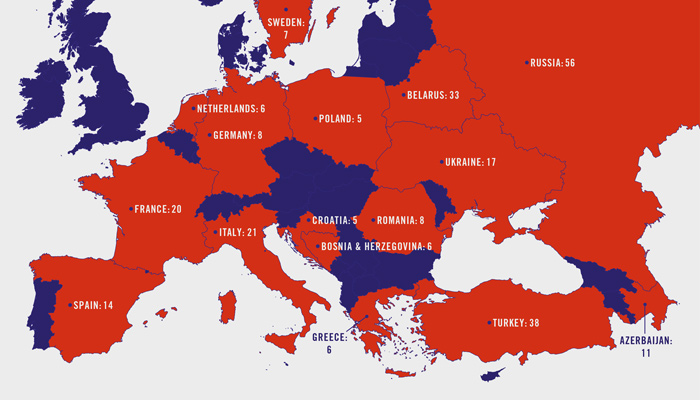

Journalists continue to face unprecedented pressure in Europe as reports submitted to Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom platform in the first quarter of 2017 demonstrate. Media professionals—primarily in Turkey, Russia, Belarus and Ukraine—were arrested at an alarming rate, more than a fourfold increase over the fourth quarter of 2016.

“During the first quarter of 2017, the MMF database registered several trends that we find to be acute challenges to media freedom. Some European governments have clearly interfered with media pluralism. Others have harassed, detained and intimidated journalists. All of these actions debase and devalue the work of the press and undermine a basic foundation of democracy,” Hannah Machlin, project manager at Mapping Media Freedom, said.

During Q1, authorities in multiple countries shut down critical and independent media outlets and intimidated reporters who asked challenging questions. Turkey continues to be the largest jailer of journalists in the world with a total of 148 journalists in prison by the end of March according to the Platform for Independent Journalists P24, a Turkey-based MMF partner, which monitors the number of arrests in the country.

Even reporters in countries often thought to respect freedom of the press, such as Sweden, France and Germany, faced obstacles to performing their professional duties. They were abused by the leaders of extreme populist movements and their supporters, who encouraged a distrust of “mainstream media”; and blocked by nervous politicians who were seeing, particularly in France, the old political certainties swept away.

Between 1 January and 31 March 2017, Mapping Media Freedom’s network of correspondents and other journalists submitted a total of 299 violations of press freedom to the database.

The full report can be found online at Mapping Media Freedom or in PDF format.

17 Jul 2017 | Digital Freedom, Mapping Media Freedom, Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News and features, Ukraine

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Ukrainian post control before separatist zone (Credit: Geoffrey Froment/Flickr)

Soon after the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation, full-scale fighting began between Ukrainian troops and separatists supported by Russia in the east of Ukraine. During active fighting in 2014, it was relatively easy for journalists to access to territories controlled by separatists.

“Accreditation was given quickly and without delay,” a Ukrainian producer who worked with international TV channels said. The producer, who requested anonymity because of ongoing work in the area, admits the risk for journalists was high because of the chaotic situation on the frontline and many of them faced detention by separatist militants. “I, like many, was detained and placed in a basement, but, fortunately, it only lasted for several hours,” he added.

Anna Nemtsova, a correspondent for Newsweek magazine and The Daily Beast, told Mapping Media Freedom that in 2014 she was abducted twice – firstly in the Luhansk region and secondly in the city of Donetsk.

“These were classic abductions,” Nemtsova said. “In Luhansk region, near Krasny Luch, armed militia wearing masks took our cell phones away from us and drove us in an unknown direction. In Donetsk, it happened near the morgue, where, according to our information, the militia had brought some of the bodies of passengers of the downed Boeing MH-17. Both detentions lasted for a few hours.”

Soon the situation with journalists’ access to uncontrolled territories would change for the worse. In February 2015, the Minsk agreements were signed and a ceasefire was established. The ceasefire agreement prompted the authorities of the two self-proclaimed republics to start monitoring journalists’ reports from the Donetsk People’s Republic and Luhansk People’s Republic.

“If they did not like the angle of coverage or some term, for example ‘separatist republics’, the name of a journalist was immediately added to the list of undesirable persons. The press service began to summon such journalists to ‘talks’ to express their dissatisfaction,” source who works as a local TV producer told MMF.

Nemtsova also faced similar difficulties. In summer 2015 she was told that the DPR press service did not like her reports and threatened to ban her, which later they said they did. “Their complaints were unreasonable, they were not about any errors in my report, but about the term ‘separatists’, which they claimed I used in my stories,” she said.

Thus, the monitoring of publications about the separatist zone in the media has led to the fact that from the summer of 2015 many journalists who tried to obtain accreditation from the self-proclaimed authorities began to receive refusals. Some reporters who managed to enter the territory of the self-proclaimed republics were detained and deported. On 16 June 2015, separatists from DPR captured Novaya Gazeta special correspondent Pavel Kanygin and handed him over to Russian security services (FSB). According to the journalist, they checked his documents and released him “in the middle of a field.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator color=”black” align=”align_left”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Ukraine” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fmappingmediafreedom.org%2F|||”][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship monitors press freedom in Ukraine and 41 other European area countries.

As of 17/07/2017, there were 282 verified reports of violations connected to Ukraine in the Mapping Media Freedom database.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”94239″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://mappingmediafreedom.org/”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black” align=”align_left”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Over the past year, arbitrary refusals to enter the territory of the self-proclaimed republics have been quite frequent. In December 2016, Deutsche Welle’s correspondent Christian Trippe and his crew were barred from entering the territory of the self-proclaimed DPR. Journalists were trying to get to the territory controlled by DPR at a checkpoint near Marinka. Journalists had to wait an hour in a neutral zone between two fronts, while they were not allowed to return to the territory controlled by Ukrainian forces. The crew had received an authorisation from DPR press centre and had scheduled an interview with a spokesperson for the separatists. The journalists planned to visit Donetsk with Principal Deputy Chief Monitor Alexander Hug of the OSCE Special Monitoring Mission to Ukraine. However, the militants did not let them through the checkpoint with the OSCE, citing the decision of DPR special services.

In 2016, the self-proclaimed authorities continued the practice of detentions and expulsions of journalists. In November, special forces of the self-proclaimed Donetsk People’s Republic detained and expelled two journalists working for Russian TV channel Dozhd. Correspondents Sergei Polonsky and Vasiliy Yerzhenkov were detained by intelligence agencies on the evening of 25 November in Donetsk. Polonsky said that members of the self-proclaimed Ministry of State Security went to their apartment and took them to the main building of the ministry where they were interrogated. “Three employees of the Ministry of State Security were involved in the interrogation. They watched videos and deleted them. They also blocked Polonsky’s phone, broke Yerzhenkov’s phone and destroyed his notebook,” Dozhd reported. According to Dozhd, the journalists were not physically abused. “We experienced psychological abuse, but nothing more,” Polonsky said. Later, employees of the Ministry of State Security explained to the correspondents that their detention was a consequence of “false information” in the accreditation, which turned out to be a wrong phone number.

The Dozhd crew were accredited to work in Donetsk by the Security Service of Ukraine and by the Ministry of information of DPR. Journalists entered the DPR border on 24 November from Russia to interview Alexey Khodakovsky, former secretary of DPR’s Security Council. Previously, the self-proclaimed Ministry of State Security of DPR said the cause of the journalists’ expulsion was “biased” and “provocative” coverage of the situation in the DPR.

Local journalists and bloggers often find it even more risky to work in the separatist territories. In 2014, many journalists were forced to leave the territory, and are now working elsewhere in Ukraine. Over the past year, a number of arrests by separatists have been reported. The latest one is an incident with blogger and writer Stanyslav Aseev who disappeared in Donetsk. The blogger was reportedly detained by militants of the self-proclaimed DPR. Aseev uses the alias Stanislav Vasin and contributes to a number of news outlets including Radio Liberty Donbass Realities project, Ukrayinska Pravda, Ukrainian week and Dzerkalo Tyzhnya. He also runs a prominent blog via Facebook.

Donbass Realities project editor-in-chief Tetyana Jakubowicz said their contact with Aseev was lost on 2 June. That day, Aseev filed the latest report from territories held by separatists for Radio Liberty. Aseev’s relatives and friends confirmed that they also lost contact with the blogger. They questioned the self-proclaimed Ministry of Public Security of the DPR, but didn’t receive any answers. The journalist’s mother found evidence that his flat was broken into in Donetsk and noticed that some of his belongings were missing, including a laptop. On 12 July, Amnesty International reported that it learned that Aseev was being held by the de-facto “ministry of state security”.

Recently, several bloggers have been arrested in the self-proclaimed LPR. In October 2016 Vladislav Ovcharenko, a 19-year old blogger, who runs the Twitter account Luhansk Junta, was detained by separatists. Later, armed representatives of the self-proclaimed Ministry of the State Security raided his parents’ apartment, taking his mother’s computer. In December 2016, Facebook blogger Gennadiy Benytskiy was arrested in Luhansk. The blogger, who is known for his pro-Ukraine views, was accused of distributing of “extremist materials” online.

Journalists take risks even when they get accreditation from the separatist authorities. A leak by the website Myrotvorets in May 2016 led to the personal data of more than 5,000 journalists becoming available online. The link to the leak was published by some Ukrainian politicians, calling journalists who received accreditation “traitors.” Some of the journalists then received threats.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

14 Jul 2017 | Azerbaijan, Digital Freedom, Mapping Media Freedom, Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Afgan Mukhtarli. Credit: Meydan TV

Media outlets in Azerbaijan routinely deal with torture, assault, raids, imprisonment and endless intimidation, as verified reports submitted to Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project show.

“The years-long crackdown on the independent press by the regime of Ilham Aliyev has accelerated in recent months. This is clearly one of the world’s worst environments for press freedom and, consequently, for the public’s right to information,” Hannah Machlin, project manager for Mapping Media Freedom, said.

International media freedom rankings confirm the country’s stagnating record where autocratic repression is consistent, if not the functioning political system itself. Although authorities continue to claim that the majority of the country’s 147 political prisoners are criminals, religious radicals and tax evaders, the international community of rights watchdogs view it differently. A new wave of attacks against media freedom advocates, journalists and activists within the past two months alone illustrate a place where the primacy of Ilham Aliyev, Azerbaijan’s president, and his word overrides the primacy of the words of others, particularly his critics.

One such critic, Afgan Mukhtarli, an investigative journalist, disappeared on 29 May while on his way to his home in Tbilisi. Mukhtarli reappeared the next day across the border in Azerbaijan and was accused of illegal border crossing, smuggling (police allegedly found €12,000 on him) and resisting police. He was immediately sentenced to three months in pre-trial detention.

Speaking to Mapping Media Freedom, Mukhtarli’s wife Leyla Mustafayeva said she was relieved when she heard news of his arrest because after reporting her husband missing the day before, she had assumed he was dead. However, that is the only relief Mustafayeva has had since her husband’s kidnapping:

“I have no hope for the investigations. They have been stalled. They don’t want to investigate. Police allegedly cannot find any footage. The only video that was made available to our lawyer was shown two weeks after Mukhtarli’s disappearance and it’s just of my husband getting on the bus that usually takes him home.”

Mukhtarli’s case is unique in that his is the first cross-border operation alleged to be carried out in tandem with the Georgian government. While this has yet to be confirmed by officials in Georgia, Azerbaijani lawmaker and a member of the Parliament Human Rights Committee Elman Nasirov claimed Mukhtarli’s kidnapping was “the most successful operation carried out in recent years.” Nasirov also accused Mukhtarli of being a member of a far larger anti-Azerbaijan network.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator color=”black” align=”align_left”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Mapping Media Freedom: Azerbaijan” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fmappingmediafreedom.org%2Fplus%2F%3Fs%3DAzerbaijan|||”][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship monitors press freedom in Azerbaijan and 41 other European area countries.

As of 14/07/2017, there were 60 verified reports of violations connected to Azerbaijan in the Mapping Media Freedom database.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”94222″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://mappingmediafreedom.org/#/”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black” align=”align_left”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]“Muktharli was assigned to carry out subversive activities in Azerbaijan,” Nasirov asserted, claiming that as a preventive mechanism, Azerbaijani special forces made necessary arrangements with Georgian special forces. “The are principles and rules for this. Based on security principles, this how it was made possible to bring Mukhtarli to Azerbaijan,” said Nasirov in an interview with Azadlig Radio, the Azerbaijani service for Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty.

Police have questioned political activists, members of opposition parties, and journalists as part of the investigation. Sevinc Vagifqizi, a freelance reporter, was detained while waiting for news outside the state border services where Mukhtarli was being held. Speaking to journalists after her brief detention, Vagifqizi said that police allegedly thought she was going to disturb peace outside the building. Other journalists who have been questioned in the case of Mukhtarli are investigative journalist Khadija Ismayilova, who is facing a travel ban despite her release from jail, and, more recently, Aytac Ahmadova.

The circumstances of Mukhtalri’s arrest were notably suspicious. Outside of his abduction, Mukhtarli’s lawyer was also quick to report on the injuries Mukhtarli suffered, including a broken nose, multiple bruises and possibly a broken rib. Mukhtarli is not the only journalist who appears to have been subjected to alleged police brutality. Nijat Amiraslanov, a member of the NIDA civic movement and an independent journalist based in Gazakh, reportedly lost his front teeth while serving his 30-day administrative detention. In his statement, however, Amiraslanov said his teeth fell out on their own, and that there was no ill-treatment during his detention. After Amiraslanov’s teeth fell out, the journalist refused an appeal filed by his lawyer. Amiraslanov was released on 21 June after completing the detention period.

In another show of force, police raided the office of independent online television channel Kanal 13 on 3 June, confiscating computers and other documents. Police had already detained the channel’s manager Aziz Orucov (Garashoglu) earlier in May. Orucov was sentenced to 30 days of administrative detention on the grounds of allegedly resisting police. Additional charges of illegal entrepreneurship and abuse of power were brought against Orucov on the day of his release. He was sentenced to four months in pre-trial detention.

While these men await trial, another journalist and editor-in-chief of the news website Journalistic Research Center (jam.az) Fikrat Faramazoglu was sentenced to seven years in jail on 14 June. Faramazoglu was found guilty on charges of extortion. In his defence statement, the journalist said it was his reporting on a chain of brothels that were protected by the law-enforcement agencies that incited his arrest. Faramazoglu was also banned from working as a journalist for two years following the completion of his prison term.

A classic case of revolving door policy

Rather than continue to release its political prisoners, the Azerbaijani government continues to arrest more reporters and further tightens controls on the media sector.

“There are some ten journalists and bloggers currently in prison [in Azerbaijan]. Based on these new arrests, Azerbaijan is trying to return to the list of countries where journalists critical of the government end up in jail on bogus charges,” said Muzaffar Suleymanov from the Civil Rights Defenders, a Stockholm-based rights watchdog in an interview with Mapping Media Freedom. Furthermore, a recent decision by a Baku court to block access to independent and opposition news websites broadcasting from abroad is a matter of more concern, added Suleymanov.

Levan Asatiani from Amnesty International echoed these sentiments adding that, as an international community of watchdogs, they have not seen any improvements, only a further deterioration in the human rights situation in Azerbaijan.

“While there have been releases, there have been new arrests or travel bans introduced against former prisoners of conscience,” Asatiani said. There are also legal boundaries in place that prevent the work of remaining independent civil society organisations in Azerbaijan.

It is no longer enough to make statements and express concern says Suleymanov. The Council of Europe should hold its members responsible for violating human rights while the EU must set benchmarks in accordance with the human rights situation as it negotiates a new agreement with Azerbaijan, noted Asatiani.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1500022088088-43842239-2fe8-0″ taxonomies=”7145″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

11 Jul 2017 | Digital Freedom, Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, News and features, Ukraine

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Alongside the digitalisation of journalism comes the increasing danger of cyber-attacks on media workers. Reporters in Ukraine have faced a string of such attacks recently, including cyberbullying, the blacklisting of websites and ransomware viruses, as reports to Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project show.

“Online threats have become increasingly prevalent throughout Ukraine, and the climate of impunity that exists within the country prevents these cases from being taken seriously,” Hannah Machlin, the project manager at Mapping Media Freedom, said. “Index calls upon the Ukrainian authorities to investigate instances of online harassment more thoroughly and hold offenders accountable.”

Machlin urges Ukraine to “adhere to European press freedom standards by ceasing to censor the media, including pro-Russian websites”. Furthermore, she urges both the Ukrainian government the international community to “increase investments in digital security efforts”.

Hromadske TV journalist Nastya Stanko was the victim of a cyberbullying campaign. The harassment began on 10 June when Stanko received official thanks from Ukrainian Ministry of Defense “for significant contribution to the development of national war journalism”.

Katya Gorchinskaya, Hromadske TV executive director, claimed that the campaign against Stanko was a clear example of anonymous cyberbullying. “It’s not just a campaign against Stanko, this is just one example of harassment against journalists doing their work,” Gorchinskaya told Detector Media. “We saw many similar incidents last year, and this persecution is not only against those who spoke and wrote about the situation on the frontline, but also those who were writing about corruption in governance. Hromadske TV, Radio Liberty, Ukrayinska Pravda, Novoe Vremiya, OCCRP and all investigative journalists in general – they all suffer from such harassment.”

On 19 June, the Ministry of Information Policy released a list of 20 websites that it plans to ban, many of which are considered to be pro-Russian. These are: rusvesna.su, rusnext.ru, news-front.info, novorosinform.org, nahnews.org, antifashist.com, antimaydan.info, lug-info.com, novorossia.today, comitet.su, novoross.info, freedom.kiev.ua, politnavigator.net, odnarodyna.org, zasssr.info, ruspravda.info, on-line.lg.ua, ruscrimea.ru, c-pravda.ru and 1tvcrimea.ru.

According to the ministry, this list was compiled by experts and was sent to the Security Service of Ukraine. It believes that these websites violate Ukrainian legislation by fuelling ethnic and interethnic hostility, calling for the overthrow of the constitutional system, violating the territorial integrity of the country and violating legislation on decommunisation.

This comes after a 15 May decree by Petro Poroshenko, the country’s president, that bans a number of Russian media and social media websites including VKontakte and Odnoklassniki along with the search engine Yandex and the email service Mail.ru.

On 30 June Ukrainian news websites Korrespondent.net and Komsomolskaya Pravda were blocked for three days as a result of a ransomware attack known as Petya. A message on Korrespondent.net read: “Dear visitors, the site’s work was blocked by a massive virus attack. Our team is currently working hard to resume its work in the near future.”

According to Ukrainian police, 1,508 companies and individuals filed complaints about computers being locked by the Petya virus, which encrypts data on a computer and demands a ransom to release access. The attack is assumed to be a part of the 27 June large-scale hack which began in Ukraine, targeting the government, banks, enterprises and media outlets. Attacks also took place in Italy, central Europe, Israel, Germany and Russia.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]