14 May 2020 | Covid 19 and freedom of expression, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

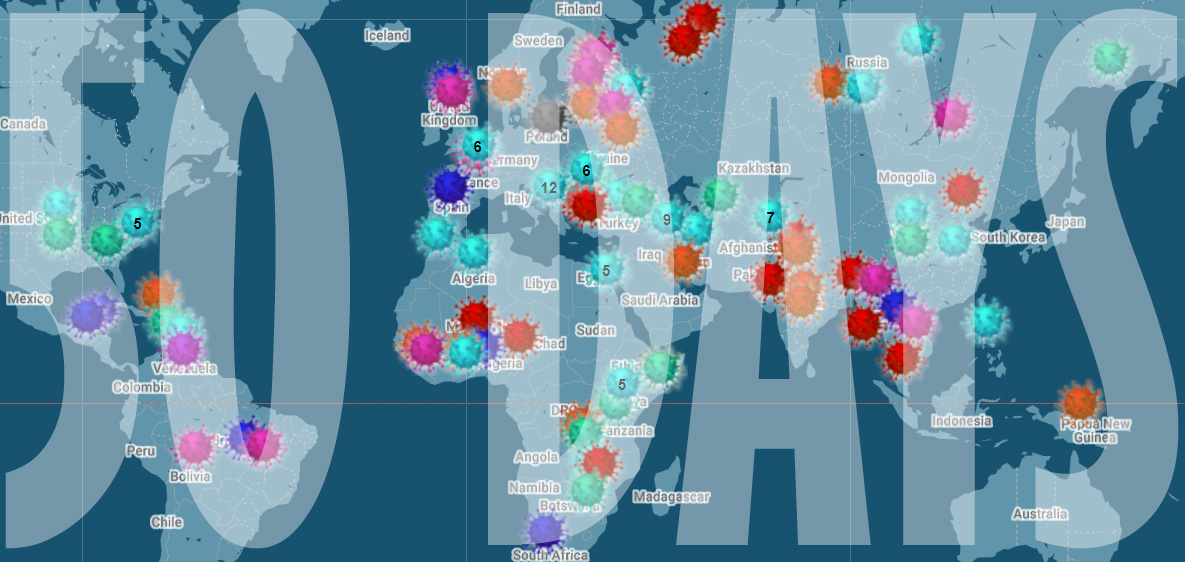

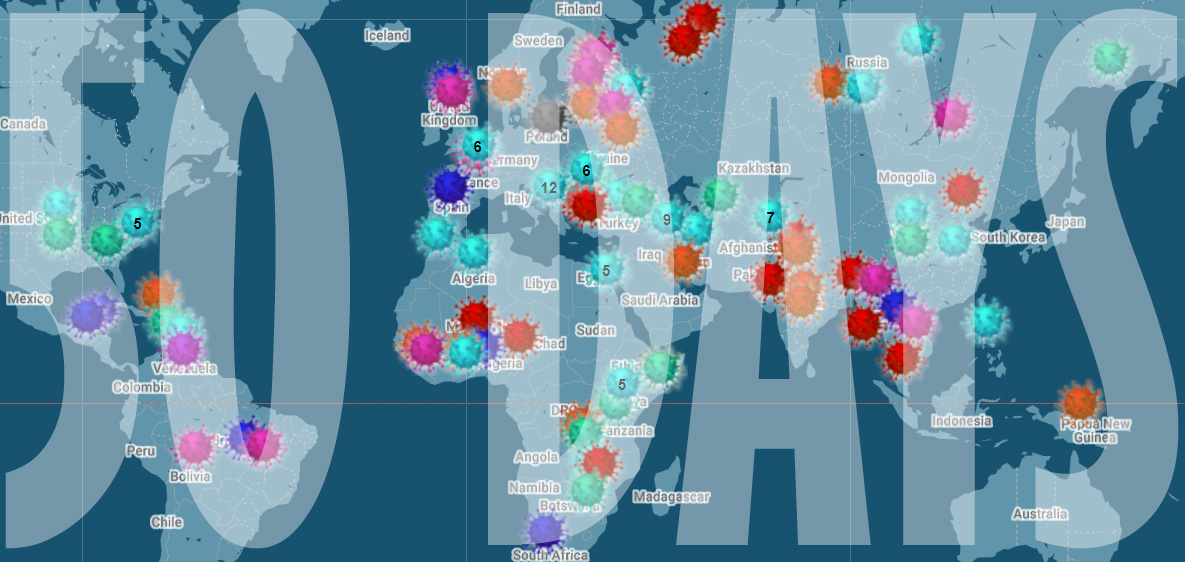

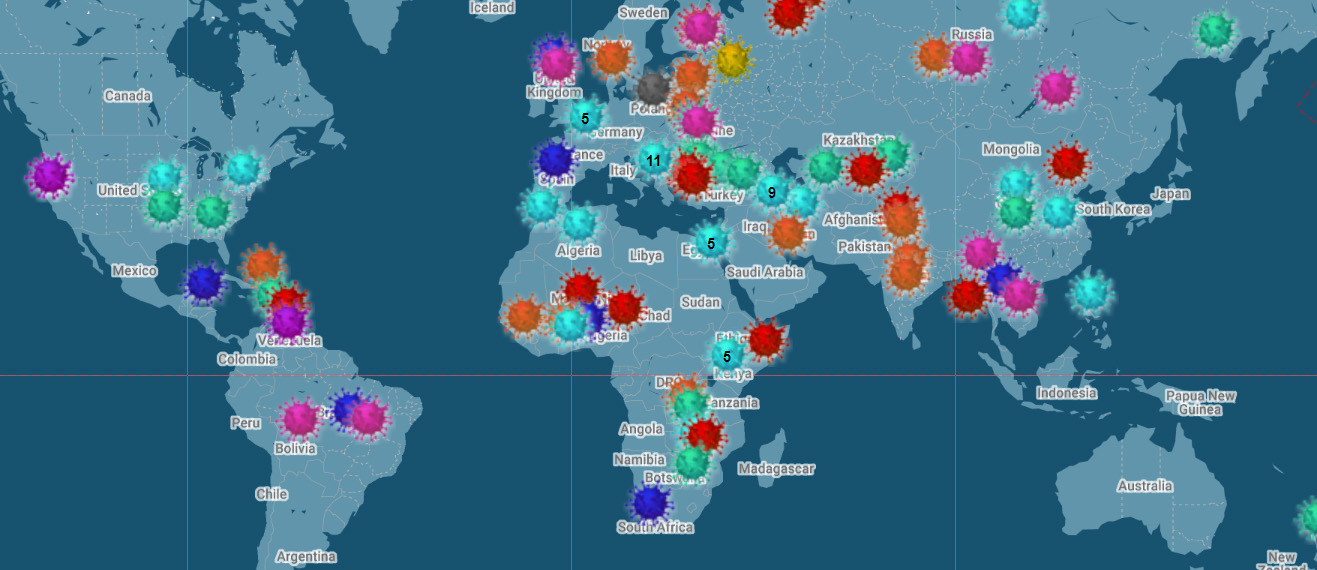

As we mark 50 days since we first started collating attacks on media freedom related to the coronavirus crisis, we’re horrified by the number of attacks we have mapped – over 150 in what is ultimately a short period of time.

We know that in times of crisis media attacks often increase – just look at what happened to journalists after the military coup in Egypt in 2013 and the failed coup against Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Turkey in 2016. The extent of the current attacks, in democratic as well as authoritarian countries, has been a shock.

Our network of readers, correspondents, Index staff and our partners at the Justice for Journalists Foundation have helped collect the more than 150 reports media attacks.

But these incidents are likely to be the very tip of the iceberg. When the world is in lockdown, finding out about abuses of power is harder than ever. Journalists are struggling to do their job even before harassment. How many more attacks are happening that we don’t yet know about? It’s a scary thought.

Rachael Jolley, editor-in-chief of Index on Censorship, said: “We are alarmed at the ferocity of some of the attacks on media freedom we are seeing being unveiled. In some states journalists are threatened with prison sentences for reporting on shortages of vital hospital equipment. The public need to know this kind of life-saving information, not have it kept from them. Our reporting is highlighting that governments around the world are tempted to use different tactics to stop the public knowing what they need to know.”

Index is alarmed that the attacks are not coming from the usual suspects. Yes, there have been plenty of incidents reported in Russia and the former Soviet Union, Turkey, Hungary and Brazil. At the same time there have been many incidents in countries you would not expect to see – Spain, New Zealand, Germany and the UK.

The most common incident we have recorded on the map are attacks on journalists – whether physical or verbal – and cases where reporters have been detained or arrested. There have been more than 30 attacks on journalists, with the source of many of these being the US President Donald Trump. He has a history of being combative with the press and decrying fake news even where the opposite is the case and the crisis has seen a ramped up attempt at excluding the media. During the crisis, he has refused to answer journalists’ questions, attacked the credentials of reporters and walked out from press conferences when he doesn’t like the direction they are taking.

We have also seen reporters and broadcasters detained and charged just for trying to tell the story of the crisis, including Dhaval Patel, editor of the online news portal Face of Nation in Gujarat, Mushtaq Ahmed in Bangladesh and award-winning investigative journalist Wan Noor Hayati Wan Alias in Malaysia.

Since we started the mapping project, we have highlighted other specific trends. Orna Herr has written about how coronavirus is providing pretext for Indian prime minister Narendra Modi to increase attacks on the press and Muslims. Jemimah Steinfeld wrote about how certain leaders are dodging questions while we have also looked at how freedom of information laws are being suspended or deadlines for information extended.

Although the map does not tell the whole story it does act as a record of these attacks. When this crisis is finally all over, it will allow us to ask questions about why these attacks happened and to make sure that any restrictions that have been introduced are reversed, giving us back our freedom.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_btn title=”Report an incident” shape=”round” color=”danger” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fforms.gle%2Fhptj5F6ZvxjcaGLa7|||” css=”.vc_custom_1589455005016{border-radius: 5px !important;}”][/vc_column][/vc_row]

4 May 2020 | India, News

Image by Raam Gottimukkala from Pixabay

A friend in the police department apologetically texted me with some “friendly” advice. “Don’t be extra active on social media over corona issues which may lead to panic and rumours. There may be legal issues over it,” he said.

He wouldn’t elaborate further, but it didn’t take much to understand. A freelance journalist was arrested in Andaman and Nicobar Islands for a tweet on a bizarre quarantine rule. At least 13 people from various walks of life have been arrested since 1 April in Manipur for Facebook posts. A doctor at a government hospital had been harassed by the police and questioned for 16 hours at a police station after he put up a Facebook post complaining about the lack of protection gear for doctors. A founder of an online publication was arrested in Tamil Nadu for reports on problems faced by government healthcare workers. In Chhattisgarh, a journalist was slapped with a notice threatening arrest for his report on the plight of women in lockdown.

The pandemic has given the government free rein. India is witnessing very high levels of suppression of free speech and media censorship across the country.

“Everything is censored,” said a Kolkata-based journalist, declining to be identified. “You cannot report on anything that is not confirmed by the government. Getting data on anything is an ordeal.”

In the name of curtailing rumours and fake news, there have been curbs on free speech and freedom of journalists to cover the pandemic, especially those with questions that make the government uncomfortable. “It’s as if the media is an opponent. It is as if asking questions of the government is a crime, or a politically motivated exercise,” said the journalist.

On 30 March, Scroll.in published a list of ten questions that health beat reporters in Delhi had for the central government but did not get any answers. These included: How did the Indian government arrive at the pricing of the Covid test in private labs, which is Rs 4,500 ($60), and among the highest in the world? Why has the drug controller not released the list of Covid-19 testing kits that have been granted import and manufacturing licences? What are the steps the government is taking to map the scale of Covid-19 outbreak in the community? What arrangements have been made to ensure patients living with life-threatening conditions like cancer, tuberculosis and HIV that require continuous support are not deprived of critical care?

While questions such as these remain unanswered, journalists covering the Covid crisis say they are witnessing unprecedented levels of censorship. Government interaction with the press is stressed. Prime Minister Modi, in keeping with his record, has not organised a single press conference on the issue. Harsha Vardhan, a health minister, has interacted infrequently with the press, while the daily press briefings are conducted by a senior bureaucrat in the health department, Lav Agarwal.

“In the ministry’s organisation structure,” writes Vidya Krishnan in Caravan magazine, “Agarwal comes after two secretaries, four special secretaries and four additional secretaries, and is one of the thirteen joint secretaries in the ministry of health.”

Even the press briefings are not for all journalists. Barring Doordarshan (DD), India’s public broadcaster, and news agency Asian News International and a few accredited journalists, others have been barred from attending the press briefings in the name of social distancing. “The directive on social distancing became an excuse to not have journalists in the room,” said Anoo Bhuyan, Delhi-based health reporter with Indiaspend, a data journalism-based news portal.

“Then we got a message one day saying other than ANI and DD no one needs to attend the press conference. They said we could send our questions through WhatsApp. However, there is no guarantee that your question will be picked to be answered by Mr Agarwal. It is like a lucky draw without any rationale and definitely does not give equal chances to all journalists. In the very short time allotted for questions, only two to four questions are picked up, some of which are repetitions.”

The Modi-led government even approached India’s Supreme Court to legalise censorship by seeking an order that would prevent the media to publish anything “without ascertaining the true factual position” from the government. The court did not go that far, only directing the media to “refer to and publish the official version about developments”.

“The order itself does not have teeth, but the fact that there is an order may freak out many,” said Bhuyan. “It gets diabolical in that Lav Agarwal makes it a point to sometimes refer to the order and ‘remind’ journalists to ‘exercise caution’ and ‘report responsibly’.”

“What’s happening in India is extremely disturbing,” Vidya Krishnan, a Goa-based health reporter with Caravan magazine, tweeted on April 1. There is a media gag in place, doctors have been threatened to not speak out against lack of PPE kits, and the health ministry says we have no local transmission (without scaling up testing). Genuinely struggling to understand how we can continue reporting in this Orwellian setting.”

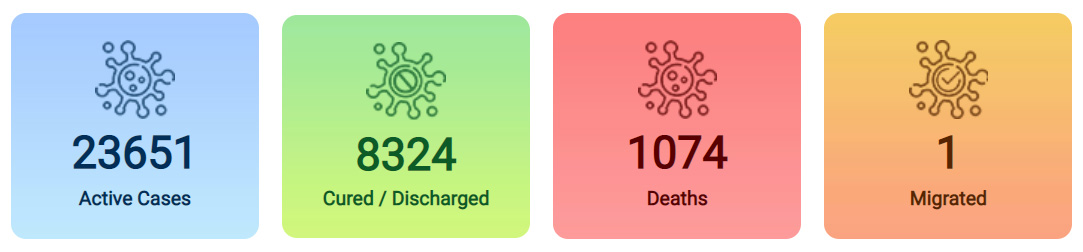

Source: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, data correct as at 30/4/2020

Meanwhile, Mamata Banerjee, chief minister of the Indian state of West Bengal, announced insurance cover for journalists covering Covid from the frontlines. It is a combination of medical and life cover worth 10 hundred thousand Indian rupees (£10,500). There’s one rider: journalists have to do “positive” stories. “People are depressed seeing negative news all the time,” she said. “Journalists should be involved with the government,” she added without leaving anything to doubt.

This came just two days after she threatened legal action against journalists if they report “unconfirmed” fatality figures. Banerjee, who has a record of booking journalists, academics and the general public for social media posts critical of her, faces allegations that she is supressing Covid-related data in the state. The state has a special committee to “audit” and “ascertain” Covid deaths.

Banerjee has asked journalists to “behave properly” or face legal action.

1 May 2020 | Covid 19 and freedom of expression, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Governments are using the Covid-19 crisis to change freedom of information laws and, unless we are very careful, important stories could get unreported. Since the beginning of the crisis, governments from Brazil to Scotland have made changes to their FOI laws; some of the changes are rooted in pragmatism at this unprecedented time; others may be inspired by more sinister motives.

FOI laws are a vital part of the toolkit of the free media and form a strong pillar that supports the functioning of open societies.

According to a 2019 report by Unesco – published some two and a half centuries after the first such law was introduced in Sweden – 126 countries around the world now have freedom of information laws. These typically allow journalists and the general public the right to request information relating to decisions made by public bodies and insight into administration of those public bodies.

US president Thomas Jefferson once wrote: “Whenever the people are well informed, they can be trusted with their own government; that whenever things get so far wrong as to attract their notice, they may be relied on to set them to rights.”

Now in this time of crisis, freedom of information processes are being shut down, denied unless they relate specifically to the crisis or the deadlines for responses are being extended.

When the Covid-19 crisis first erupted, we made a decision to monitor attacks on media freedom. It wasn’t just a random idea; we know that in similar times of crisis, repressive governments often attack the work that journalists do – sometimes the journalists themselves – or introduce new legislation they have wanted to do for some time and now see a time of crisis as an opportunity to do so without proper scrutiny.

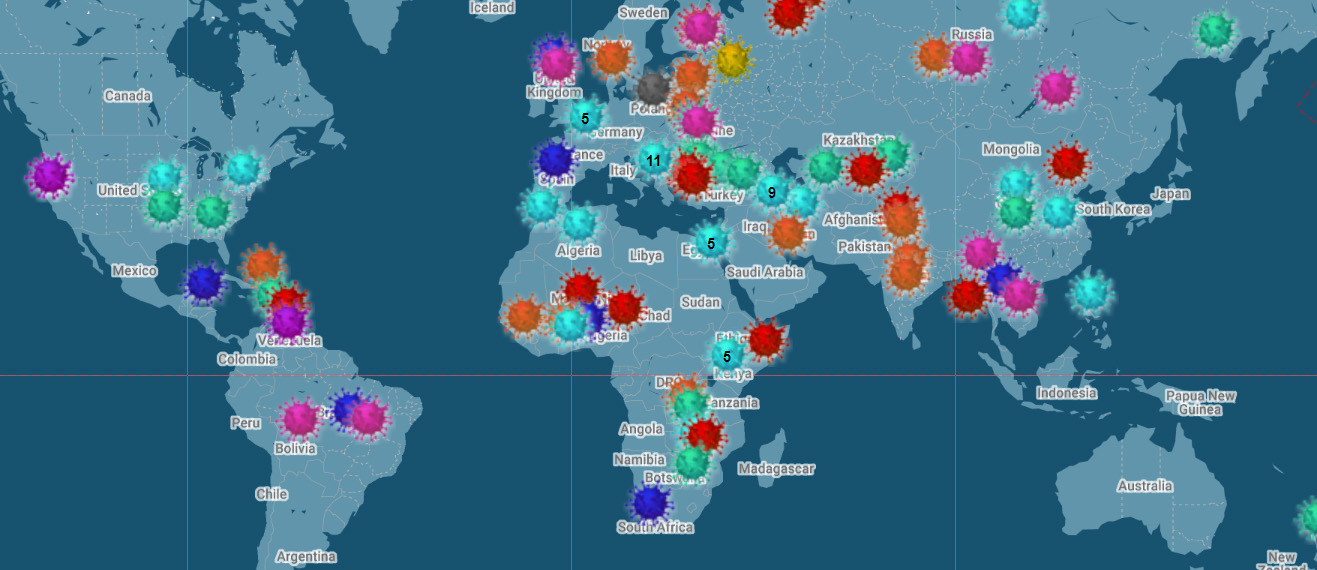

Since the start of the crisis, we have been collecting reports on attacks on media freedom through an innovative, interactive map. More than 125 incidents have been reported by our readers, our network of international correspondents, our staff in the UK and our partners at the Justice for Journalists Foundation. Many relate to changes to FOI legislation.

Let us be clear there can be legitimate reasons for amending legislation in times of international crisis. With many public officials forced to work from home, many do not have access to the information they need or the colleagues they need to consult to be able to answer journalists’ requests. Others need more time to be able to put together an informed response.

Yet both restrictions and delays are worrying. They allow politicians and public bodies to sweep information that should be freely available and subject to wider scrutiny under the carpet of coronavirus. News that is three months old is, very often, no longer news.

In its Coronavirus (Scotland) Bill, the Scottish government has agreed temporary changes to the Freedom of Information (Scotland) Act 2002 that extend the deadlines for getting response to information requests from 20 to 60 working days. The initial draft wording sought to allow some agencies to extend this deadline by a further 40 days “where an authority was not able to respond to a request due to the volume and complexity of the information request or the overall number of requests being dealt with by the authority”. However, this was removed during the reading of the bill following concerns raised by the Scottish information commissioner.

The bill was passed unanimously on 1 April and became law on 6 April. As it stands the new regulations remain in force until 30 September 2020 but can be extended twice by a further six months.

In Brazil, President Jair Bolsonaro has issued a provisional measure which means that the government no longer has to answer freedom of information requests within the usual deadline. Marcelo Träsel of the Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalism says the measure is “dangerous” as it gives scope for discretion in responding to requests.

The decree compelled 70 organisations to sign a statement requesting the government not to make the requested changes, saying “we will only win the pandemic with transparency”.

Romania and El Salvador are among the other countries which have stopped FOI requests or extended deadlines. By contrast, countries such as New Zealand have reocgnised the importance of FOI even in a crisis. The NZ minister of justice Andrew Little tweeted: “The Official Information Act remains important for holding power to account during this extraordinary time.”

FOI law changes are not the only trends we have noticed.

Index’s deputy editor Jemimah Steinfeld has noted how world leaders are ducking questions on coronavirus while editorial assistant Orna Herr has written about how the crisis is providing pretext for Indian prime minister Narendra Modi to increase attacks on the press and Muslims.

If you are a journalist facing unreasonable delays in receiving information from public bodies at this time, do report it to us at bit.ly/reportcorona.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

29 Apr 2020 | News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Attacks on press freedom in Europe are at serious risk of becoming a new normal, 14 international press freedom groups and journalists’ organisations including Index on Censorship warn today as they launch the 2020 annual report of the Council of Europe Platform to Promote the Protection of Journalism and the Safety of Journalists. The fresh assault on media freedom amid the Covid-19 pandemic has worsened an already gloomy outlook.

The report analyses alerts submitted to the platform in 2019 and shows a growing pattern of intimidation to silence journalists in Europe. The past weeks have accelerated this trend, with the pandemic producing a new wave of serious threats and attacks on press freedom in several Council of Europe member states. In response to the health crisis, governments have detained journalists for critical reporting, vastly expanded surveillance and passed new laws to punish “fake news” even as they decide themselves what is allowable and what is false without the oversight of appropriate independent bodies.

The report analyses alerts submitted to the platform in 2019 and shows a growing pattern of intimidation to silence journalists in Europe. The past weeks have accelerated this trend, with the pandemic producing a new wave of serious threats and attacks on press freedom in several Council of Europe member states. In response to the health crisis, governments have detained journalists for critical reporting, vastly expanded surveillance and passed new laws to punish “fake news” even as they decide themselves what is allowable and what is false without the oversight of appropriate independent bodies.

These threats risk a tipping point in the fight to preserve a free media in Europe. They underscore the report’s urgent wake-up call on Council of Europe member states to act quickly and resolutely to end the assault against press freedom, so that journalists and other media actors can report without fear.

Although the overall response rate by member states to the platform rose slightly to 60 % in 2019, Russia, Turkey, and Azerbaijan – three of the biggest media freedom violators – continue to ignore alerts, together with Bosnia and Herzegovina.

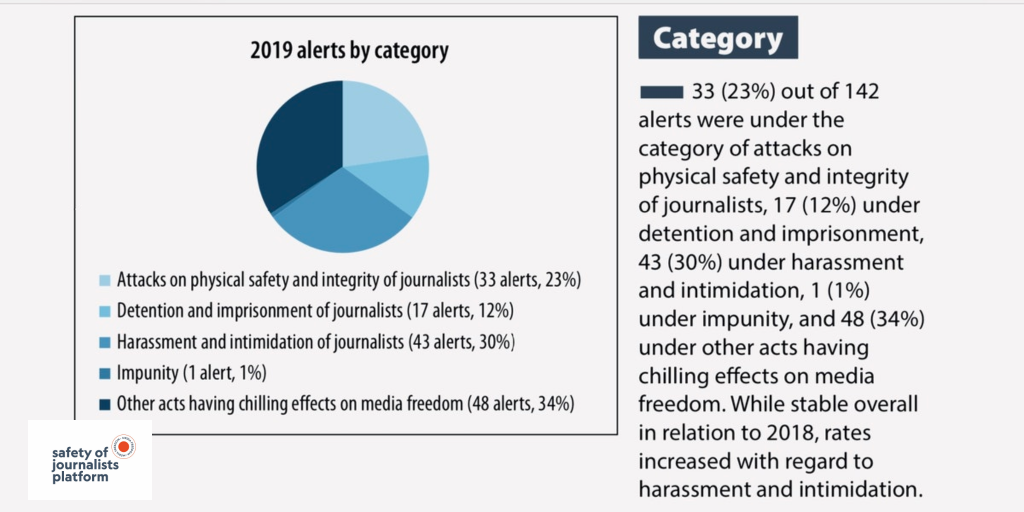

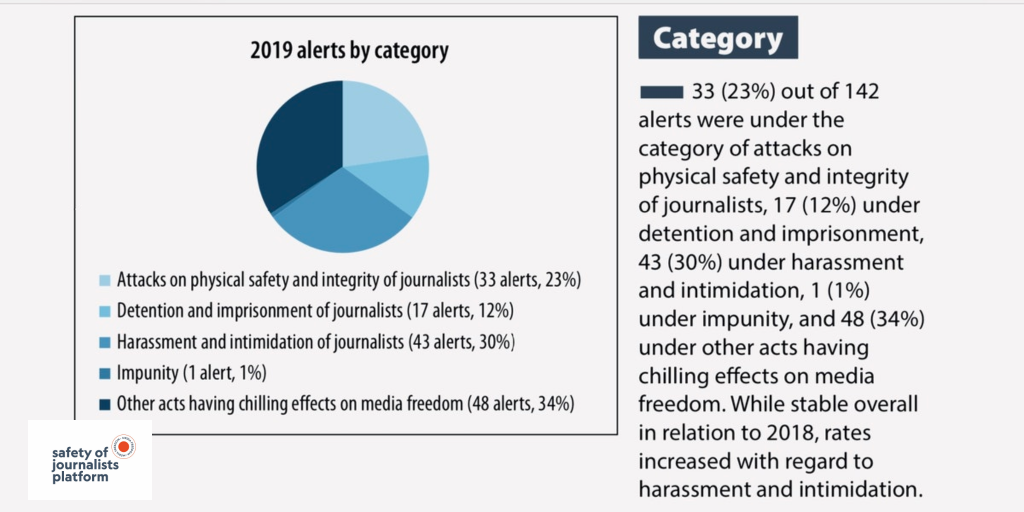

2019 was already an intense and often dangerous battleground for press freedom and freedom of expression in Europe. The platform recorded 142 serious threats to media freedom, including 33 physical attacks against journalists, 17 new cases of detention and imprisonment and 43 cases of harassment and intimidation.

The physical attacks tragically included two killings of journalists: Lyra McKee in Northern Ireland and Vadym Komarov in Ukraine. Meanwhile, the platform officially declared the murders of Daphne Caruana Galizia (2017) in Malta and Martin O’Hagan (2001) in Northern Ireland as impunity cases, highlighting authorities’ failure to bring those responsible to justice. Only Slovakia showed concrete progress in the fight against impunity, indicting the alleged mastermind and four others accused of murdering journalist Ján Kuciak and his fiancée, Martina Kušnírová.

At the end of 2019, the platform recorded 105 cases of journalists behind bars in the Council of Europe region, including 91 in Turkey alone. The situation has not improved in 2020. Despite the acute health threat, Turkey excluded journalists from a mass release of inmates in April 2020, and second-biggest jailer Azerbaijan has made new arrests over critical coverage of the country’s coronavirus response.

2019 saw a clear increase in judicial or administrative harassment against journalists, including meritless SLAPP cases, and spurious and politically motivated legal threats. Prominent examples were the false drug charges filed against Russian investigative journalist Ivan Golunov and the continued imprisonment of journalists in Ukraine’s Russia-controlled Crimea. The Covid-19 crisis has strengthened officials’ tools to harass journalists, with dangerous new “fake news” laws in countries such as Hungary and Russia that threaten journalists with jail for contravening the official line.

Other serious issues identified by 2019 alerts included expanded surveillance measures threatening journalists’ ability to protect their sources, including in France, Poland and Switzerland, as well political attempts to “capture” media through ownership and market manipulation, most conspicuously of all in Hungary. These threats, too, are exacerbated by the actions taken by several governments under the health crisis, which further include arbitrary limitations on independent reporting and on journalists’ access to official information about the pandemic.

Jessica Ní Mhainín, Index’s policy research and advocacy officer, says, “There is a growing pattern of intimidation aimed at silencing journalists in Europe. The situation in Eastern Europe – especially in Hungary, Poland, and Bulgaria – is particularly concerning. But the killing of Lyra McKee shows that we cannot take the safety of journalists for granted anywhere – not even in countries that are seen to be safe for journalists. This report provides an opportunity for us all to come to grips with the serious situation that is facing European media and to remind ourselves of the vital role that the media play in holding power to account.”

Index and the other platform partners call for urgent scrutiny of action taken by governments to claim extraordinary powers related to freedom of expression and media freedom under emergency legislation that are not strictly necessary and proportionate in response to the pandemic. Uncontrolled and unlimited state of emergency laws are open to abuse and have already had a severe chilling effect on the ability of the media to report and scrutinise the actions of state authorities.

While the platform welcomes an increased focus on press freedom by European institutions, including both the Council of Europe and European Union institutions, the ongoing crisis demands more urgent and stringent responses to protect media freedom and freedom of expression and information, and to support the financial sustainability of independent professional journalism. In the age of emergency rule, protecting the press as the watchdog of democracy cannot wait.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]