1 Dec 2016 | European Union, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

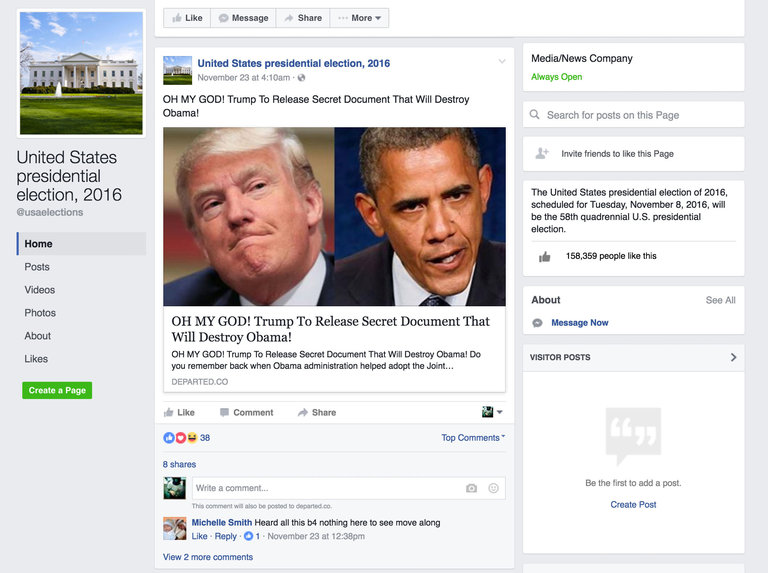

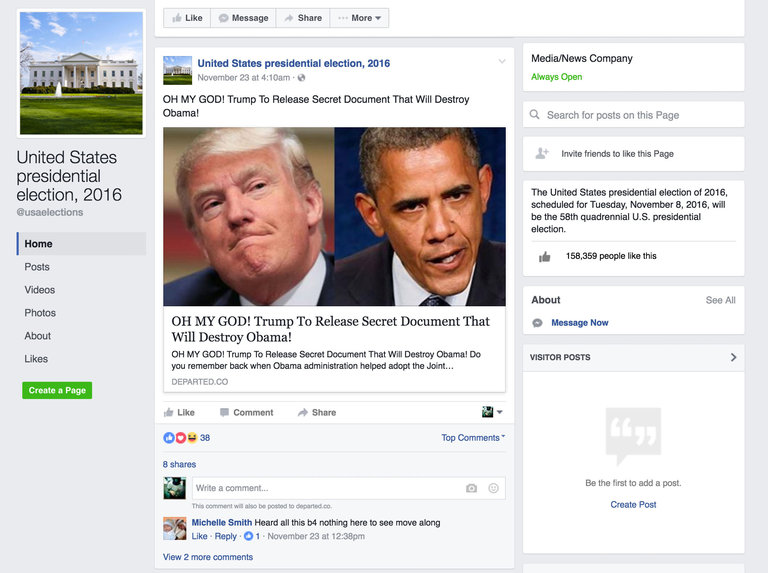

Social media is all atwitter these days with the unremarkable discovery that people lie.

So much so that Oxford Dictionaries has designated “post-truth” as its international word of the year. For those of you not hip to the jargon, it means “relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief.”

In other words, facts don’t count.

Perhaps spawned by the spate of alleged news stories made up out of whole cloth during the recent presidential election in the United States, people of all stripes are weighing in on the issue du jour: How can we ensure that what we read on Facebook or Twitter is real?

I ask, “Why bother?”

Consider the Ninth Commandment (or Eighth, at least as interpreted by Catholics and Lutherans): “Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbour.”

That sounds like a dire warning against lying, which was something that must have been quite popular during the day, and still is. Besides going to hell, most every country in the world has libel laws designed to compensate people whose reputations have been damaged by lies.

But today the allegation of lying seems to be taking on more sinister effects. There have been some allegations that false news stories actually swung votes in the US presidential election. If so, why is “fake news” so effective? I believe we can go back to Lord Mansfield’s 18th century dictum “the greater the truth, the greater the libel” for some insight. Whether we just want to believe something is true or we pick and choose our truths to match our political cloth, we find ourselves in an era where we can scan a headline, read the lede and say, “That seems believable enough.”

Thus, manufacturing stories out of thin air has become a cottage industry and an apparently successful one.

Trying to get on the perceived “right side” of the issue, it comes as little surprise that social media companies such as Facebook are engaged in damage control, saying they are trying out new versions of their algorithms to weed out postings that are simply made up.

And to that I again ask, “Why bother?”

For in fact, doing so may just cause greater harm to free expression than any lie, no matter how damaging.

Because besides the difficulty in determining truth from opinion to a bald-faced lie, the inherent limiting of ideas, including criminalising them, makes us all suffer a little bit.

Today we are seeing criminal and administrative prosecution for activities on social media platforms that involve responding to existing content (i.e. sharing, re-posting, uploading, liking, quoting and commenting) and that contributes to an environment of fear.

Combine this with the growing tendency for nations to apply anti-extremism and anti-terrorism laws to content on social media platforms and the result is social media users, including members of the media, are being fined, arrested and imprisoned for interacting or reacting to content produced by third parties or for expressing their opinions on it.

This is censorship and can lead to self-censorship.

Instead, issues related to social media activities should be addressed exclusively through self-regulation, education and literacy, not through new restrictions.

As the Representative on Freedom of the Media for the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, I recently recommended that the participating states that comprise the body to recognize the following:

- That no one should be penalised for social media activities that come as a reaction or interaction with existing content;

- That no one should be penalised for the social media activities such as posting and direct messaging unless they can be directly connected to violent actions and satisfy the test of an “imminent lawless action”;

- That no one should be held liable for content on social media platforms and on the internet of which they are not the author, as long as they do not specifically intervene in that content or refuse to comply with court orders to remove that content, where that have the capacity to do so (“mere conduit principle”);

- The necessity to decriminalise defamation, insult and blasphemy;

- That any imposition of any sanctions imposed by courts of law, especially when it comes to social media activities, should be in strict conformity with the principle of proportionality;

- The need for education and literacy on freedom of expression on the internet.

Let’s not overreact to the wave of fake news by building another wall around the internet.

Dunja Mijatović is the Representative on Freedom of the Media for the OSCE, based in Vienna.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1480348630223-46408dc4-0b68-7″ taxonomies=”6380″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

23 Nov 2016 | News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

A crowd of protesters prevent police from arresting journalists in Istanbul, Turkey, December 2014. Credit: Sadik Gulec / Shutterstock.

The following is a speech given by Index on Censorship trustee David Schlesinger at last week’s News Agencies World Congress in Baku, Azerbaijan.

A journalist is not a soldier. A pen is not a menace. A camera is not a gun.

Yet to far too many crooked governments, evil despots, corrupt moguls or power-mad militias, a journalist is more of a threat than even an armed opponent is. Their fear is that the journalist’s pen can write the story of suffering or malfeasance; the journalist’s camera can capture an image of the truth; the journalist’s story can move readers to tears – or more threateningly, to action.

So journalists are harassed, kidnapped and killed. Access to information is made difficult or cut off completely. Transparency becomes opacity. And the loser is society.

This is not an argument about democracy over another form of government. This is not an argument about systems of rule or the strengths or weaknesses of one leader over another. This is very simply an argument that for any society to function well, its people need to be informed.

Without knowledge, there is no accountability. Without accountability, there is only despotism and corruption. Every good system of government needs honesty and transparency to keep its legitimacy long term. Journalists and journalism need to be recognised and treasured as vital players in this struggle.

And yet they are not.

Some governments refuse access to news sites. Some leaders refuse to hold press conferences. Some prosecute journalists and their sources for legitimate newsgathering. Some harass reporters and their families, making the journalists’ choice of profession a serious liability. Some turn a blind eye when bullies and thugs use violence against journalists to stop their reporting. Some governments themselves take horrible physical vengeance on reporters, forcing them to put their bodies and souls in jeopardy in service of their calling.

In the words of the Committee to Protect Journalists: Murder is the ultimate form of censorship.

Since 1992, according to the CPJ, 1,210 journalists have been killed while reporting. Of those, 796 were murdered.

Death is not a danger merely for war correspondents – in some countries, reporters on almost every beat step into peril daily. Maybe their reporting offends a local boss. Maybe they get too close to a drug story, or a corruption story. Maybe they have to go into a dangerous no-man’s-land in search of the key fact or illuminating interview. Maybe they’re targeted simply for asking questions or appearing curious.

Of those journalists murdered, CPJ found that some of the targeted covered a business beat, some covered corruption, some covered crime, some covered culture, some covered human rights, some covered politics, some covered sports, some covered war. That’s nearly every beat imaginable, nearly every beat important to a media institution.

And the truly horrifying fact is that most of these murders are never investigated thoroughly, let alone punished.

Thus, all of us in the media sector should celebrate and recognise the importance of United Nations Security Council resolution 2222, adopted unanimously in May 2015, that strongly condemned the culture of impunity for violations and abuses committed against journalists in situations of armed conflict. This resolution emphasised the responsibility of all UN member states to comply with their obligations under international law to end impunity and to prosecute those responsible for serious violations of international humanitarian law.

This was hugely important.

We must take comfort in the fact that the United Nations recognised the important work that journalists do in conflict zones and that it condemned attacks against them and demanded the end to a culture of impunity.

But we must also remember that horrific violence against journalists and the culture of impunity exists outside of armed conflict zones as well. Violence stalks the reporter covering links between police and the drug trade, the reporter combing through business records to track down corruption, the reporter uncovering government malfeasance and maladministration, the reporter asking too many questions of an overly sensitive strongman.

And we must also remember that despite the passage of resolution 2222 a year and a half ago, the problem has not gone away; the killings and murders have continued; the lack of accountability and justice remains.

This is unacceptable.

We at this conference have both a duty to take a stand and an opportunity to take constructive and important action.

First, we who have been or still are in the mainstream media have an obligation to open the eyes of the public and policy makers to the fact that the definition of journalists today is much broader than just the types of people here in this room.

We cannot think of bloggers, social media tweeters and independent reporters as the competition or – worse yet – as not of our profession. We must think of them as colleagues, and we must demand that the world look at them in the same way as it looks at us.

A door closed in the face of a blogger is a door closed in the face of every one of us. An independent journalist denied access to a press conference is merely a forerunner to one of us here being denied the next time. A freelancer kidnapped or injured or killed is a gaping, hurting wound on the entire profession.

We dishonour ourselves if we dishonour those who report in different ways or with different tools or with different employment statuses. We who have some position and status within our countries have an obligation to ensure that our colleagues who don’t currently have that respect get it. We must ensure that any protections that come to us also go to them.

Then, we must lobby and advocate for better access, better safety protections and an end to impunity for crimes against journalists. This is a convention of journalists with strong ties in their home bases. Many here are from national news agencies. The struggle must begin at home.

There is no country that has a perfect record in terms of access to information or safety for journalists. Every single one of our nations must do better. We can help make that happen.

When you leave this conference and return home, meet with policy makers. Insist that UN resolution 2222 be implemented fully and completely and that your country take a strong stand in favour of its spirit.

Meet with policy makers and insist that issues of journalistic access and safety extend beyond conflict zones and into the arena of domestic reporting, no matter how sensitive that may be. Make the case that journalism, no matter how uncomfortable, is for the good of society and that the legitimacy of that society is dependent on transparency.

Progress must begin at home, and we who are in this room and in this organisation have a privileged position with which to press the case Our profession has no meaning unless we are working in the service of truth and transparency. We cannot accept doors being slammed in our faces, lights being turned out on us and guns being trained on our bodies.

Let’s open the doors, turn on the lights and push the guns aside. Let’s call out against justice systems that allow impunity for crimes against journalists. Show them for what they are: enablers of crimes against truth. Let’s take a side, and insist that our nations’ leaders take a side, in favour of free flow of information, freedom of expression and freedom from the fear that just, honest, truthful reporting can get the journalist jailed or killed.

Those who are doing the reporting on the ground, in the conflict zones, in the records office, and in the corrupt localities are being incredibly brave.

Let us – we who are in the editors’ chairs, we who are in the executive suites, we who are in the conference centres, safe behind the front lines – let us match their bravery by supporting their rights to exist, be free, be safe and be full members of our profession.

A journalist is not a soldier, but he or she does fight for a cause. A pen is not a menace, but it is a weapon in the fight for truth and justice. A camera is not a gun, but it is a tool in the fight to record society for what it is.

And we need to ensure this fight is fought in safety.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1479899967488-4da3e1f3-2169-1″ taxonomies=”6564″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

8 Sep 2016 | Counter Terrorism, Digital Freedom, Europe and Central Asia, News

(Illustration: Shutterstock)

The appalling scene on the strand in Nice on Bastille Day. The dead at the airport and in the Metro in Brussels in March. Terrorist attacks, designed to inflict the highest possible level of fear and apprehension among ordinary citizens, is now ordinary in Europe.

The stakes were raised in earnest in January 2015 with the carnage at the editorial offices of the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo in Paris, where 10 staffers were brutally murdered by terrorists.

How can such atrocities be avoided or squelched? That is the question.

We know Europeans want something to be done. Living in a perpetual state of fear is not the natural consequence of living in 21st century liberal democracies.

But neither is living in a police state, where personal privacy gives way to the exigencies of war, however unlike this war compares to ones of the past; where mere idle chatter can be misconstrued to the point that it becomes the criminal offense of glorifying terrorism.

Simply put, do our rights to personal privacy and free expression and free association vanish in order to provide a safer physical environment for our residents?

The answer, or answers are not easily arrived at; the debates are nuanced and people of good will and good character can find themselves on opposite sides of issues while both hoping for a similar outcome: peace, security and an open society that respects the inherent rights of individuals to live freely.

Under these difficult circumstances, I think it is important to make the case, once again, to protect individual rights in times of civil turmoil. To do so, I issued a statement earlier this month, as the OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media setting out the arguments in favour of protection.

First and foremost, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, the world’s largest regional security body, appears fully on board with the notion of protection of these individual rights. The participating States, in the Astana Declaration of 2010, reiterated the commitment to comprehensive security and related the maintenance of peace to respect for human rights.

And in a Ministerial Council Decisions on Preventing and Countering Violent Radicalization that Lead to Terrorism and on Counter-terrorism that was adopted in 2015, the States confirmed the notion “..that respect for human rights, fundamental freedoms and the rule of law are complementary and mutually reinforcing with effective counter-terrorism measures, and are an essential part of a successful counter-terrorism effort.”

Furthermore, any counter-terrorism measures restricting the right to free expression and free media must be in compliance with international standards, most notably Article 19 of the UN Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and strictly adhere to the principles of legality, necessity and proportionality and implemented in accordance with the rule of law.

Read alone, these pronouncements ought to put an end to any notion that the rights and values inherent in an open society should not survive the fight against terrorism. But it has not. Across the OSCE region, which comprises 57 countries from North America to Mongolia, governments are considering laws that chip away at those fundamental rights.

As a result, I have suggested that lawmakers of OSCE participating States give ample weight and consideration to the following when addressing any legislation that would affect, in law or in practice, the right of people to exercise their human rights:

- Ensure journalists’ freedom and safety at all times, including while reporting on terrorism.

- Recognize that free expression and the use of new technologies are also tools to fight terrorism by creating social cohesion and expressing alternative narratives.

- Clearly and appropriately define, in line with international human rights law, the notions of violent extremism, terrorism, radicalisation and other terms used in legislation, programs and initiatives aimed to prevent and counter terrorism.

- Acknowledge that the media has a right to report on terrorism. Requests for media blackouts of terrorist activities must be avoided and media should be free to consider, based on ethical standards and editorial guidelines, available information to publish in the public interest.

- Fully respect the right of journalists to protect sources and provide a legal framework securing adequate judicial scrutiny before law enforcement and intelligence agencies can access journalists’ material in terror investigations.

- Refrain from indiscriminate mass surveillance because of its chilling effect on free expression and journalism. Targeted surveillance should be used only when strictly necessary, with judicial authorization and independent control mechanisms in place.

- Acknowledge that anonymity and encryption technologies may be the only guarantee for safe and secure communications for journalists and therefore are a prerequisite for the right to exercise freedom of expression. Blanket prohibitions are disproportionate and therefore unacceptable, and encryption regulation introducing “backdoors” and “key escrows” to give law enforcement and intelligence access to “the dark web” should not be adopted.

- Only restrict content that is considered a threat to national security if it can be demonstrated that it is intended to incite imminent violence, likely to incite such violence and there is a direct and immediate connection between the expression and the likelihood of occurrence of such violence.

- Review applicable laws and policies on counter-terrorism and bring them in line with the above principles.

Adherence to these simple rules is necessary because limiting the space for free expression and civic space advances the goals of those promoting, threatening and using terrorism and violence.

If we give up on our fundamental freedoms we will erode the very substance of democracy and the rule of law.

Recent columns by Dunja Mijatović

Dunja Mijatović : Turkey must treat media freedom for what it really is – a test of democracy

Dunja Mijatović: Why quality public service media has not caught on in transition societies

Dunja Mijatović: Chronicling infringements on internet freedom is a necessary task

28 Jul 2016 | mobile, News, Turkey

Büşra Erdal, one of 89 journalists subject to arrest, surrendered in Manisa and was taken to police headquarters in handcuffs.

Media freedom must be treated for what it really is: a strong test of democracy. And any response to a crisis requires a cautious approach if basic civil liberties, the building blocks of any free society, are to be protected. Make no mistake about it, in the case of Turkey, we are faced with a situation where authorities are violating the basic human right of Turkish citizens to engage in free media.

Just consider the following media freedom issues that have taken place after the attempted coup in Turkey on 15 July.

- The authorities have ordered the closure of 45 newspapers, 15 magazines, 16 television channels, 23 radio stations, 3 news agencies, and 29 publishers;

- Arrest warrants have been issued against 89 journalists, accusing them of supporting terrorism; seven of them have already been detained;

- 370 journalists at the state broadcaster TRT have been suspended;

- Press accreditations for 34 journalists from eight other Turkish media outlets have been revoked;

- 60 staff members with Cihan News Agency have been fired;

- The Radio and Television Supreme Council of Turkey (RTÜK) has cancelled the licenses of more than 20 radio and television stations;

- The Telecommunications Authority (TIB) has blocked more than 20 news websites.

These issues must also be put in the context of the general, sharply deteriorating media freedom situation in Turkey in the past few years. An anti-terror law in Turkey, in effect since 1991, is being used to round up terrorists but also many others, including those who it is my job to lobby for – journalists and media.

Today there are dozens of journalists in jail in Turkey, prosecuted and convicted mostly under a law designed to fight terrorism and protect people. The number of journalists jailed in Turkey is without precedent in the OSCE region. Under the anti-terror law, merely reporting on controversial topics could land a journalist in court.

The latest case in a string of the recent crackdown activities on media in Turkey is the detention of seven journalists in the last two days, while arrest warrants were issued against several dozens more, accusing them of supporting terrorism. To say that dissenting voices, although still present and persisting, are under duress in Turkey is a severe understatement.

The authorities’ systematic abuse of media and its players, done with the intention of guaranteeing control of the media landscape, is nothing short of a clear and present threat to democracy in the country.

Media-freedom advocates like myself, must and will continue to raise our voices and provide the defenses necessary for free expression and free media to flourish in Turkey.

I will raise the issue of the rights of media and of journalists before national legislatures. I will engage in public awareness campaigns on behalf of free media. I will continue to do everything in my power to protect and safeguard the independent and pluralistic voices that are the cornerstones of any society. And I will call on elected officials to spend the resources, including political capital, essential to build environments conducive to free expression.

I believe that a society that respects human rights is working towards the common good of its people and that limiting and breaching fundamental democratic and civil liberties negatively affects the common good. I also believe that the role of elected officials is to write good laws and appoint good law enforcement authorities, including police, prosecutors and judges to interpret those laws in a manner that will make free expression possible.

All democratically elected governments must adhere to the underlying rules of their society – free markets, universal suffrage, access to government information and other basic civil liberties, including a free and pluralistic media environment.

Freedom of expression is a universal and basic human right; it does not stop at views deemed appropriate by the authorities. It remains the role of journalists to inform people of public issues, including highly sensitive issues. And it remains the role of the authorities to ensure that journalists, no matter how critical or provocative, can do so freely and safely. Turkey fails on this account.

More commentary from Dunja Mijatović

Why quality public service media has not caught on in transition societies

Chronicling infringements on internet freedom is a necessary task

Propaganda is ugly scar on face of modern journalism

More about Turkey

Yavuz Baydar: Erdogan is ruling Turkey by decree

Can Dündar: Turkey is “the biggest prison for journalists in the world”

Turkey’s film festivals face a narrowing space for expression