16 Jul 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News, Serbia

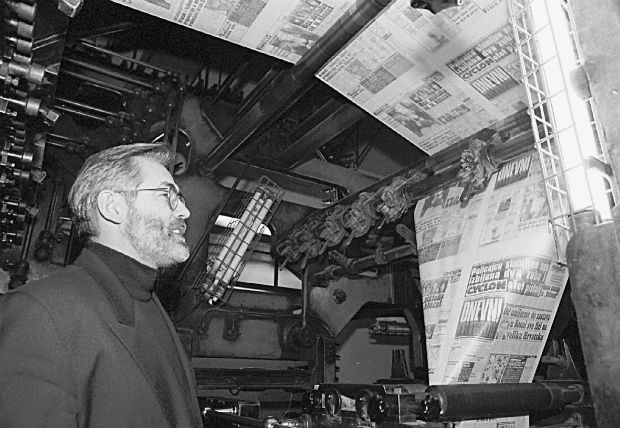

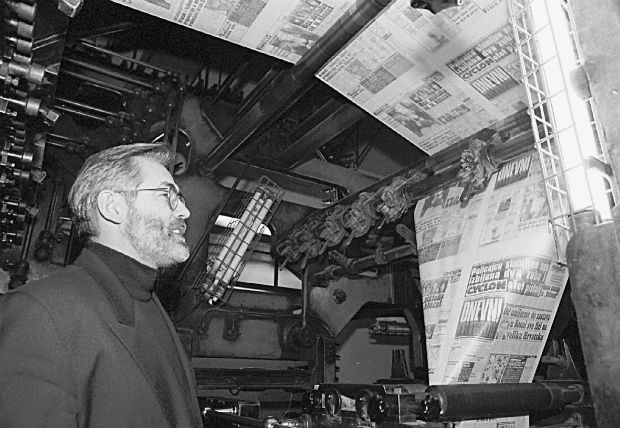

Journalist Slavko Curuvija, murdered in Belgrade in 1999 (Photo: Predrag Mitic)

As NATO bombs were falling on the Serbian capital Belgrade on 11 April 1999 , a man was being executed on a side street in the centre of the city. The victim was later identified as Slavko Curuvija, a prominent Serbian anti-regime journalist. A post mortem found that Curuvija had been shot in the back 17 times. Five days earlier the state-run daily Politika Ekspres had published an article calling Curuvija a traitor and a NATO supporter.

Fast forward to 1 June 2015: the trial of four former security officers begins before a special court in Belgrade. It took 16 years for anyone to stand trial over what had become a notorious case of intimidation of journalists in Serbia.

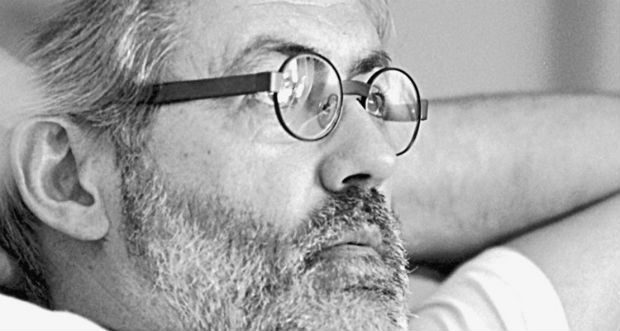

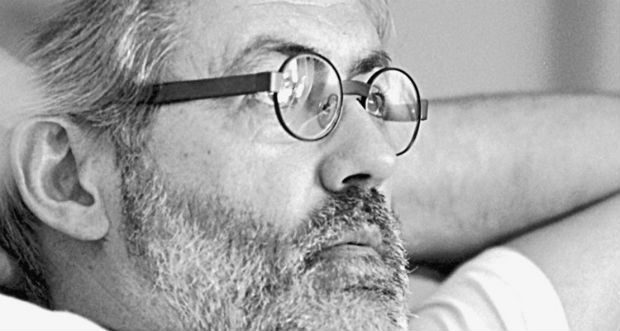

Much of the credit for pursuing a cause by many considered lost can go to veteran journalist Veran Matic, the editor-in-chief of media group B92.

Several Serbian governments had shown no signs that they were willing to solve Curuvija’s case; the same goes for many other war-time murders. For years, Matic and his fellow journalists would mark the anniversary of Curuvija’s death by laying flowers at Svetogorska Street, where he lived and died, and by raising awareness in the media and with the government. It was not enough.

In 2013, Matic was fed up with waiting for answers about the murders of his colleagues. He proposed to form a special body to investigate the killings of Curuvija and two other journalists. Prime Minister Aleksandar Vucic — then deputy prime minister — gave Matic permission to form the Commission for Investigating Killings of Journalists in Serbia. It was an unexpected move. As Curuvija was being executed on a Belgrade side street, Vucic was minister of information in President Slobodan Milosevic’s government.

“Some criticised the establishment of the commission for giving an opportunity to Vucic to clear his past,” says Matic, referring to the unease many journalists felt towards Vucic, who was highly critical towards independent media during the nineties.

“Marking every year the anniversary of the killing, visiting the place of assault, criticising the state again and again for failing to resolve those crimes became very humiliating for me,” Matic said. “In this way, I have been given another instrument through which I could do something in practice.”

It was clear that Matic needed the government’s cooperation if he wanted the murders to be solved. “I wanted to get hold of every single document and, in order to do this, we needed a commission that would be supported by the government,” he said. But Matic managed to ensure the body was made up of three representatives of the independent media, three members of the ministry of internal affairs and three representatives of the security information agency. With Matic himself serving as the commission’s chairman, journalists will always be in the majority.

Progress and challenges

(Photo: Predrag Mitic)

The commission is focusing on three big murder cases from the recent past. The work around Curuvija’s case has been the most successful until now, with four people charged. Trials for former Chief of State Security Rade Markovic and the two ex-secret service officers Ratko Romic and Milan Radonjic began 1 June. The fourth accused is Miroslav Kurak, also a former state security member and the man who is believed to have pulled the trigger on Curuvija. He is being tried in absentia, as he is still at large, an Interpol warrant issued for his arrest. There are clues that Kurak is living in Central or South Africa where he owns a hunting safari agency.

The Dada Vujasinovic case is perhaps the most difficult, as the murder took place over two decades ago. Vujasinovic was a reporter for the news magazine Duga and wrote about Zeljko Raznatovic, also known as Arkan. She was found dead in her apartment in 1994. The police ruled it a suicide, but most evidence disputes this. When the commission started working on the case, there were doubts about the forensic research done in Serbia at the time. “I decided that the first step would be to seek expertise outside of the country, as the trust in domestic institutions had been compromised,” said Matic. “We asked the Dutch National Forensic Institute based in The Hague, who offered to perform the forensic examinations for 35,000 euro. We are now raising funds for this, given that the prosecutor’s office has no budget for these services.”

The third case is that of Milan Pantic, who was murdered in June 2001 while entering his apartment building in the central Serbian town of Jagodina. Attackers broke his neck, and was also struck on the head with a sharp object. Pantic worked for the newspaper Vecernje Novosti, where he reported on criminal affairs and corruption in local companies. Prior to the killing, he had received numerous telephone threats in response to articles he had written. It’s not an easy task to investigate. “We know that one of the suspects is living in Germany under a different name,” explained Matic. “But we didn’t get permission to conduct an interview with him.”

The commission is also looking into the deaths of 16 media staffers from RTS — Serbia’s state broadcaster — who were killed during a NATO airstrike targeting its headquarters in 1999. “This is a very complex issue,” said Matic. “The executioner is certainly a pilot of one of the NATO member countries. The people who decided to put a media company on the list of war targets should face trial, as well as those who issued the order to launch missiles and kill the media workers. And also the people responsible in Serbia, who knew the building would be bombed and did not evacuate it.” NATO is refusing to cooperate in this case.

Unique commission

It is of great importance, Matic believes, that these cold cases will be solved. “Unpunished crimes, especially this committed by state institutions, only call for new violence, threats and endangerment of the safety of journalists. It leaves deep scars in the lives of journalists in this country and it contributes to censorship and fear.”

A commission like this is unique in the world; a government body controlled by independent media representatives. And its first success, the arrests in the Curuvija murder case, was surprising to many who’d lost faith in the justice system in Serbia. “This commission was not established by politicians. On the contrary, they accepted all my requests and ideas,” said Matic. “This is quite an atypical commission that works on making results, and none of its members have any political or other motives, but solely finding the killers and masterminds that hide behind the killings, and bringing them to justice.”

Jailing the head of Serbia’s secret service during the nineties, a dark period for both the country and its internal security apparatus, has come with a high price. Matic now lives under 24/7 police protection and he can’t travel anywhere without a police escort. “Some names have again been brought to light, along with their disgraceful role [in the killings]. Some are threatened with arrest, while some of them have been arrested already,” he said of the ongoing investigation.

Matic receives threats often, mostly via email, some of them to his life. But he has gotten used to having police officers in front of his door at all times because, he said, the truth is worth the compromise.

“This is the price we have to pay in order to resolve those crimes,” he said. “It will contribute to the catharsis of our society.”

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

An earlier version of this article stated that Aleksandar Vucic was interior minister when the commission was set up. This has been corrected.

This article was posted on 16 July 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

10 Jul 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, Greece, Mapping Media Freedom, News

On June, 11 2015 the Greek public TV went back to its old name “ERT”, exactly two years after its abrupt closure by the previous conservative-led government.

In June 2013 the government shut down the TV station and fired some 2,600 media workers, accusing the public broadcaster of corruption and mismanagement. Although ERT’s “sins” and disfunction were well known, the real reason behind its brutal shutdown was to meet layoff quotas laid down by Greece’s international creditors.

A few months after shuttering ERT, the government opened the New Hellenic Radio, Internet and Television (NERIT), a shrunken public broadcaster that hired employees under 3-month contracts. The budget was cut from around 300 to 100 million euros.

In April 2015, the three-month-old left wing government led by Syriza abandoned the name “NERIT” and reinstated “ERT”, which fulfilled a pre-electoral promise. It also announced that any of ERT’s 2,600 employees who wished to return to work could do so. A law setting the budget of the broadcaster at 60 million euros a year would be covered by a licence fee of three euros a month.

Under the last government, ERT was derided as bloated and biased.

“ERT is a case of an exceptional lack of transparency and incredible extravagance. This ends now,” government spokesman Simos Kedikoglou had said in a statement aired on ERT back in June 2013, announcing the government’s intention “to shut down ERT”.

On the evening of the 11 June 2013, the Greek state TV went dark for the first time since 1938, triggering outrage but also support for the shocked Greek journalists and people by the international community and press, who saw this event as example of censorship and violation of freedom of speech in crisis-stricken Greece.

“When the microphone of a journalist is cut off, it’s like the voice of democracy being silenced. This has just been brutally done to 1,300 journalists – brutally in all senses because the Greek government has sent in the police to cut off a broadcaster and stop journalists from doing their job. That is the voice of democracy, the counterweight, a pressure group, that the government, the economic power is gagging”, European Broadcast Union President Jean-Paul Philippot commented that day condemning the Greek government’s overnight shutdown of its national broadcaster ERT as an act of violence and “the worst kind of censorship”.

But, this act was not the first and only government intervention in and censorship of the state TV. An example, is that in 2012, Kostas Arvanitis and Marilena Katsimi, presenters of news-magazine “Morning Information” on NET TV were removed from the programme due to comments about Minister of Citizen Protection Nikos Dendias.

Nikos Dendias had threatened to sue The Guardian over an article about a group of Greek protesters being tortured by the police.

Arvanitis and Katsimi were told about being “cut” from the show by its editor-in-chief who was informed about the decision by the general director of ERT, just hours after the broadcast on Monday morning.

The closure of ERT triggered a wave of protests against the government’s austerity policies, during which demonstrators sent a clear message in favour of a truly public — not state — broadcaster. In the wake of the silencing of ERT, the newly unemployed journalists banded together to launch ERT Open. Ahead of the election that swept Syriza to power, the party promised a modern public broadcaster free of constraints. In announcing the reopening of ERT, the government promised “the actual fulfillment of the objectives of the public broadcasting service for information, education and entertainment of the Greek people”.

However, the new ERT relaunched amid harsh criticism from opposition parties and the press, accusing the broadcaster of promoting the left-wing government’s positions. The critics said that the reality was far from the pre-election promise of a pluralistic and objective public television station.

A government spokesperson denied any intervention and claimed that representatives of all parties were invited to participate in the first informational programmes.

According to an Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso interview with ERT’s Italy correspondent, Dimitri Deliolanes, the new government explicitly spoke of parliamentary oversight for public broadcasting. He said that for the parliament to have a control commission, as happens for example in Italy, a constitutional amendment would be needed. For this reason, the appointment of a new leadership for ERT occurred after a hearing in the parliamentary committee on transparency.

“Today ERT works well, with a very good quality standard, as competitors do not shine for sure. But the government, busy with managing the debt, has not yet managed to structure the committee. So, ERT is subject to the supervision of minister without portfolio Nikos Pappas”, Deliolanes concluded.

It remains to be seen whether Greece’s “new” public broadcaster will grow into the promised medium that is free of political intervention and the sins of the past.

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

This article was posted on 16 July 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

9 Jul 2015 | Campaigns, mobile, Statements

“Impunity is a great threat to press freedom in Russia,” said Melody Patry, Index on Censorship’s Senior Advocacy Officer. “Failing to use appropriate measures to investigate the murder of Akhmednabi Akhmednabiyev is not only a denial of justice, it sends the tacit message that you can get away with killing journalists. When perpetrators are not held to account, it encourages further violence towards media professionals.”

Statement

On the 2nd anniversary of the murder of independent Russian journalist, Akhmednabi Akhmednabiyev, we, the undersigned organisations, call for the investigation into his case to be urgently raised to the federal level.

Akhmednabiyev, deputy editor of independent newspaper Novoye Delo, and a reporter for online news portal Caucasian Knot, was shot dead on 9 July 2013 as he left for work in Makhachkala, Dagestan. He had actively reported on human rights violations against Muslims by the police and Russian army.

Two years after his killing, neither the perpetrators nor instigators have been brought to justice. The investigation, led by the local Dagestani Investigative Committee, has been repeatedly suspended for long periods over the last year and half, with little apparent progress being made.

Prior to his murder, Akhmednabiyev was subject to numerous death threats including an assassination attempt in January 2013, the circumstances of which mirrored his eventual murder. Dagestani police wrongly logged the assassination attempt as property damage, and only reclassified it after the journalist’s death, demonstrating a shameful failure to investigate the motive behind the attack and prevent further attacks, despite a request from Akhmednabiyev for protection.

Russia’s failure to address these threats is a breach of the state’s “positive obligation” to protect an individual’s freedom of expression against attacks, as defined by European Court of Human Rights case law (Dink v. Turkey). Furthermore, at a United Nations Human Rights Council (HRC) session in September 2014, member States, including Russia, adopted a resolution (A/HRC/27/L.7) on safety of journalists and ending impunity. States are now required to take a number of measures aimed at ending impunity for violence against journalists, including “ensuring impartial, speedy, thorough, independent and effective investigations, which seek to bring to justice the masterminds behind attacks”.

Russia must act on its human rights commitments and address the lack of progress in Akhmednabiyev’s case by removing it from the hands of local investigators, and prioritising it at a federal level. More needs to be done in order to ensure impartial, independent and effective investigation.

On 2 November 2014, 31 non-governmental organisations from Russia, across Europe as well as international, wrote to Aleksandr Bastrykin calling upon him as the Head of the Investigative Committee of the Russian Federation, to raise Akhmednabiyev’s case from the regional level to the federal level, in order to ensure an impartial, independent and effective investigation. Specifically, the letter requested that he appoint the Office for the investigation of particularly important cases involving crimes against persons and public safety, under the Central Investigative Department of the Russian Federation’s Investigative Committee to continue the investigation.

To date, there has been no official response to this appeal. The Federal Investigative Committee’s public inactivity on this case contradicts a promise made by President Putin in October 2014, to draw investigators’ attention to the cases of murdered journalists in Dagestan.

As well as ensuring impunity for his murder, such inaction sets a terrible precedent for future investigations into attacks on journalists in Russia, and poses a serious threat to freedom of expression.

We urge the Federal Investigation Committee to remedy this situation by expediting Akhmednabiyev’s case to the Federal level as a matter of urgency. This would demonstrate a clear willingness, by the Russian authorities, to investigate this crime in a thorough, impartial and effective manner.

Supported by

ARTICLE 19

Albanian Media Institute

Analytical Center for Interethnic Cooperation and Consultations (Georgia)

Association of Independent Electronic Media (Serbia)

The Barys Zvozskau Belarusian Human Rights House

Belorussian Helsinki Committee

Center for Civil Liberties (Ukraine)

Civil Society and Freedom of Speech Initiative Center for the Caucasus

Crude Accountability

Helsinki Citizens’ Assembly – Vanadzor (Armenia)

Helsinki Committee of Armenia

Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia

Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights

The Human Rights Center of Azerbaijan

Human Rights House Foundation

Human Rights Monitoring Institute

Human Rights Movement “Bir Duino-Kyrgyzstan”

Index on Censorship

International Partnership for Human Rights

International Press Institute

Kharkiv Regional Foundation -Public Alternative (Ukraine)

Kazakhstan International Bureau for Human Rights and Rule of Law

Moscow Helsinki Group

Norwegian Helsinki Committee

PEN International

Promo LEX Moldova

Public Verdict (Russia)

Reporters without Borders

Заявление по-русски

7 Jul 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, Hungary, mobile, News

Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, of ruling party Fidesz (Pic © European People’s Party/CreativeCommons/Flickr)

The Hungarian parliament has voted yes to plans to allow the government and other public authorities to charge a fee for the “human labour costs” of freedom of information (FOI) requests this week, as well as granting sweeping new powers to withhold information. It just needs the signature of President Janos Ader before it becomes law.

The bill, submitted by Minister of Justice László Trócsányi, was published on the government website just days before the vote, on 3 July, precluding any meaningful debate about the proposal. It is widely believed that through this initiative, governing party Fidesz is trying to put a lid on a number of scandals involving wasteful government spending, uncovered through FOI requests.

According to Transparency International, the bill “appears to be a misguided response by the Hungarian government to civil society’s earlier successful use of freedom of information tools to publicly expose government malpractice and questionable public spending”.

One provision of the bill allows public bodies to refuse to make certain data public for 10 years if deemed to have been used in decision-making processes, according to Index award-winning Hungarian investigative news platform Atlatszo.hu. As virtually any piece of information can be used to build public policies upon, this gives the government a powerful argument not to answer FOI requests.

The bill also allows government actors to charge fees for fulfilling FOI request. Until now, government actors could ask for the copying expenses of documents. From now on, they can ask the person filing the request to cover the “human labor costs” of the inquiry.

It is not yet clear how much members of the public will have to pay. “There will be a separate government decree in the future regarding the costs that can be charged for a FOI request,” Tibor Sepsi, a lawyer working for Atlatszo.hu, says.

Because the public has no means to verify whether these costs are well-grounded, and at some government agencies the salaries are known to be very high, the government might be in a discretionary position to ask prohibitive costs for answering the FOI requests, critics of the amendment say.

“The FOI requests usually ask for data that are already available somewhere in electronic format, therefore no government body can say that fulfilling a request involves gathering information,” says Tamás Bodoky, the editor-in-chief of Atlatszo.hu.

“It is unacceptable to plead for extraordinary workload and expenses when much of the requests refer to things that should be published in accordance with transparent pocket rules. This information should be readily available in the settlement of accounts and reports,” he adds.

The work of investigative journalists and watchdog NGOs is further complicated through another provision, regarding copyright. In some cases, the government will be able to refer to copyright issues and only give limited access to certain documents, without making them publicly available.

While the bill will make life harder for those making FOI requests, Sepsi also points out that the situation is not as bad as it may initially seem: “The government will have half a dozen of new ways to reject vexatious FOI requests, but on the implementation level, ordinary courts, the constitutional court or the Hungarian National Authority for Data Protection and Freedom of Information Authority will have the power to keep things under reasonable control.”

Nevertheless, Hungarian and international NGOs working for the transparency of public spending and government decisions are protesting against the bill. An open letter, signed by the groups Atlatszo.hu, K-Monitor, Energiaklub Szakpolitikai Intézet and Transparency International Magyarország Alapítvány has been sent to the Minister of Justice Trócsányi, to the Hungarian National Authority for Data Protection and Freedom of Information Authority, as well as the MPs whose votes decided the fate of the proposal.

“We believe the government would do the right thing if – instead of rolling back on transparency – it would increase the so-called proactive disclosure, meaning that it would publish the information regarding its functioning in electronic format, without a request. We can provide international examples where this can be achieved simply, without extraordinary costs. This would increase not only the transparency of public spending, but the number of FOI requests would also decrease significantly,” the letter argues.

After the vote, a group of 50 opposition MPs pledged to ask the constitutional court to review the text.

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

This article was posted on 6 July 2015 at indexoncensorship.org