23 Apr 2015 | Africa, Angola, mobile, News

Journalist and human rights activist Rafael Marques de Morais (Photo: Alex Brenner for Index on Censorship)

The trial of Rafael Marques de Morais, the investigative journalists who has exposed corruption and serious human rights violations connected to the diamond trade in his native Angola, will restart on 14 May. He was initially set to appear in court again on 23 April, but was informed of the postponement late in the evening on 22 April.

Marques de Morais is being sued for libel by a group of generals in connection to his work. The parties will be negotiating ahead of 14 May, to try and find some “common ground”, Marques de Morais told Index.

“In the interest of all parties and for the benefit of continuing work on human rights and for the future of the country, it is a very important step to be in direct contact,” he said.

“Rafael’s crucial investigations into human rights abuses in Angola should not be impeded by this dialogue. Index stresses the importance of avoiding any form of coercion,” said Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg.

Marques de Morais originally faced nine charges of defamation, but on his first court appearance on 23 March was handed down an additional 15 charges. The proceedings were marked by heavy police presence, and five people were arrested. This came just days after he was named joint winner of the 2015 Index Award for journalism.

The case is directly linked to Marques de Morais’ 2011 book Blood Diamonds: Torture and Corruption in Angola. In it, he recounted 500 cases of torture and 100 murders of villagers living near diamond mines, carried out by private security companies and military officials. He filed charges of crimes against humanity against seven generals, holding them morally responsible for atrocities committed. After his case was dropped by the prosecutions, the generals retaliated with a series of libel lawsuits in Angola and Portugal.

“Despite major differences, there is a willingness to talk that is far more important than sticking to individual positions. But this cannot impede work on human rights, freedom of the press and freedom of expression,” Marques de Morais added.

This article was posted on 23 April 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

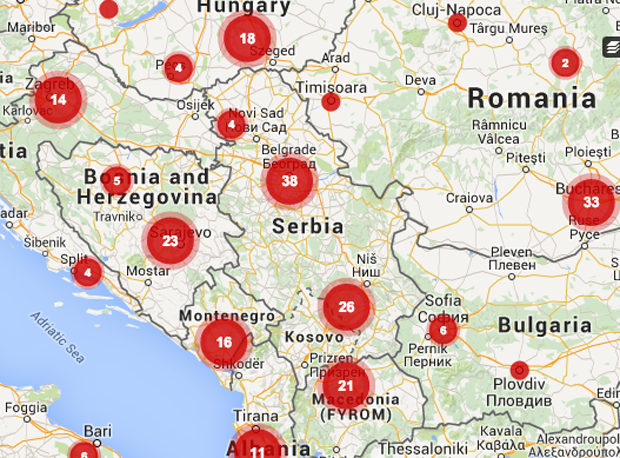

27 Mar 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News, Serbia

Working as a professional journalist in Serbia is hard. Being one in the country’s inland is even harder. Out of the 58 verified incidents involving Serbian media outlets and professionals reported to Index on Censorship’s European Union-funded Mapping Media Freedom, 30 have occurred outside Belgrade; the country’s political, economic and media capital. Four of these incidents have been directed at Juzne Vesti staff.

Launched in 2010 by journalist Predrag Blagojevic, Juzne Vesti is an independent news site based in Nis, a town of 257.000 in southern Serbia. In just over five years, its journalists have been subjected to verbal harassment or death threats 15 times. Though they have reported the incidents to local authorities, it has not resulted in convictions.

“Nobody has been found guilty and punished for the threats,” Blagojevic, who is also the site’s editor-in-chief, told Index.

According to Blagojevic, the main obstacle to punishing those threatening journalists comes from the prosecutor’s office. While he is quick to complement police in the town for their professional and timely investigations, he blames prosecutors for failing to act on the evidence by filing indictments quickly.

“In two situations from four to six months passed from the time the police filed a criminal charge to the prosecutor’s indictments,” Blagojevic explained.

Juzne Vesti correspondent Dragan Marinkovic from Leskovac received threats on Facebook after he published an article about the death of a woman, in which he questioned the treatment provided by a paramedic. He reported the incident to authorities. Several months later prosecutors decided not to pursue the case, arguing that “you deserve a bullet” is not a threat.

In March 2014 Blagojevic was threatened by the owner of a local football club, yet prosecutors waited until late September to indict the main suspect. The first court hearing was scheduled for December 2014; the next one at the end of this month.

While such delays are frustrating, once in court, judges have taken some dubious positions, Blagojevic said. In one case, the court said that “be careful what you write” or “do not play with fire” were not threats, but words that “merely showed the seriousness of the topic”. In another instance, where the perpetrator asked a Juzne Vesti staffer “Will you be alive in the morning if you wrote something like this in the USA?”, the court said that “the inductee, by placing the action in the foreign country, shows that he is aware that murder is prohibited by Serbian law”.

Outside the legal system, there is another obstacle to independent journalism in Serbia: money. While the Serbian government pays for advertising space, most of the earmarked money is directed at the national press. At the same time, the number of successful companies outside Belgrade and Novi Sad are few, and those that do thrive in the Serbian inland are usually aligned with local political figures. That leaves a tiny pool of advertisers.

“In these circumstances we are left with only very small companies, which are connected with political parties or dependent on municipal budgets. The game is straightforward — only if you are good to us you will get money,” Blagojevic said.

In an interview with SEEMO, Blagojevic described situations where certain media outlets have been financed with taxpayers’ money. With this line of funding, competing outlets are able to offer low rates that distort the advertising market, which puts pressure on independent media to drop their rates.

“The local government in Nis sets aside hundreds of millions of dinars in payment for these PR services,” Blagojevic said. The money is sometimes up to 80 per cent of the budget for these outlets making it even more difficult for independent media to compete.

The Council of Europe’s recent report on the Serbian media situation addressed the issue: “Instead of making efforts to create non-discriminatory conditions for media industry development, the state is blatantly undermining free market competition.”

The last issue confronting Juzne Vesti staff is one that will be familiar to small town journalists around the world — everyone knows everyone. Blagojevic tells of having to convince one journalist to file a complaint because she knew the person who had targeted her. She was reluctant because she had known the person “since they were kids”, he said.

From Blagojevic’s point of view, the toxic mix of money, political pressure and indifference from the courts causes self-censorship among journalists.

“The language from the 90s is back in Serbia. Again, journalists that criticise the work of the government or are reporting on corruption are labelled as foreign mercenaries. Threats like this come from the mouths of the highest state representatives,” he said.

An earlier version of this article stated that Nis has a population of 184,000. The latest census puts the figure at 257.000.

This article was posted on March 27, 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

25 Mar 2015 | Magazine, mobile, Volume 44.01 Spring 2015

A picture from the Do You See What I See project which teaches photography skills to young refugees, Zaatari camp, Jordan (Credit: Mohamed Soleman/Do You See What I See)

In an article from the refugee voices special issue of Index on Censorship Magazine, Jason DaPonte looks at how migrants are using technology to keep in touch with distant relatives, and the security risks this can bring

“My wife changes her sim card every week,” said Omid, an Iranian refugee who hasn’t seen his wife in the seven years he has been awaiting a decision in his UK asylum case. The couple use Viber, a mobile app that allows free voice calls over the internet, but his wife remains in constant fear of surveillance. Omid is wanted by the Iranian state for political offences. He’s also a convert to Christianity and his wife fears discussing his new religion, as even members of his own family have branded him an infidel.

Refugees may be some of the most excluded people in society, but social media and new technology nevertheless play a crucial role in many of their lives. Across the globe, refugees are finding ways of using them to stay connected to families, homelands and political causes, in ways they couldn’t have a decade ago – even though it can have security implications. A number of refugees, particularly from Syria, suggested they use the free messaging mobile app, WhatsApp, because they believe the messages are secure. Whether WhatsApp messages can be hacked or intercepted is not clear, however.

Ismail Einashe, a British journalist and Africa expert, originally from Somaliland, explained another way social media is changing the refugee experience. He said how his teenage cousin, who fled Somaliland for Austria, uses Facebook for photo-sharing, to craft an image of success and happiness. But this can potentially hide the true difficulties of refugee life.

“My cousin is inspired by American hiphop. He wears baseball caps and baggy jeans – so his friends at home see the glamorous ‘other’ and they don’t see the high unemployment or poverty among refugees. It’s partly encouraging the young generation. Before, people didn’t see what life on the other side could be and now they can see it,” he told Index.

Nearly every refugee interviewed for this article said that free calls on Skype and the ability to connect with relatives for free using standard social platforms (like Facebook) is invaluable to them. But for some, sharing stories from exile goes beyond simple messaging and status updates. Some refugees use blogs and social media channels to publish content banned at home to try to fight the repression they escaped.

Moses Walusimbi fled Uganda’s anti-gay laws for The Netherlands and now runs Uganda Gay On Move – a blog, Facebook and Twitter movement that helps gay Ugandans and Africans who have fled persecution, as well as providing information for those who are left behind and remain under threat.

“When I came to Holland, I realised the more you keep quiet the more you suffer,” Walusimbi told Index. “I was very eager to know if there were any other Ugandans who are in Holland who are like me, in the same situation. And when I started these social media things, many Ugandans responded.”

His movement now has almost 9,000 followers on Facebook, which he says is the most popular platform for his content. He also has followers on Twitter and his blog. Uganda Gay On Move is providing a support network that goes beyond publishing, with many photos of meetings between its members for social and political reasons.

“Uganda Gay On Move is like a family to us now. It’s like a family because we come together, we discuss, we find solutions,” said Walusimbi. These solutions have included the group petitioning and lobbying the Dutch parliament to raise awareness about the denial of the human rights of gay Ugandans and other Africans. It also publishes information that helps asylum-seekers manage their cases and gather evidence. But Walusimbi still worries about those in Uganda who could face jail sentences simply for reading it.

“Ugandan LGBTI people – unless well-known human rights defenders – tend to use false names on Facebook. There is also a danger when people attend internet cafes and do not securely log off. There is also a danger – and I have had several direct reports of family or friends seeing the Facebook pages left open on computers in homes. Some people have been exposed this way,” Melanie Nathan, an LGBTI activist and publisher who has worked closely with African LGBTI movements, told Index. “Using Facebook could result in meetings or revealing real names through trust and then in entrapment.” Walusimbi corroborated that there are real cases where this has happened.

Blogs by and for refugees from various conflict zones are building audiences. The Medeshi Somaliland blog is one example. It was founded with a desire to keep in touch with a dispersed family and diaspora in 2007 by Mo Ali, who left Somaliland to seek asylum in the UK in 2004. His work of aggregating and creating new content quickly became more political.

“There are many websites about Somaliland and those who are publishing there have been harassed by the police. They’ve been ordered to shut down because of being critical of the government on freedom of speech and press,” Ali told Index, saying he knows of at least three websites that have been shut down and explaining why he has to publish from abroad.

Even publishing from the UK, he doesn’t feel totally safe, “I’ve received death threats via email but I published the threat online and nothing happened. I’m still alive. It was just intimidation.”

Like Uganda Gay On Move, Ali has used the blog’s following to campaign, and in 2010 and 2012 rallied more than 1,000 of his followers to lobby outside London’s Parliament for official recognition of Somaliland.

Refugees are working on their own and with professional content and software creators to find bespoke ways to tell their stories. Dadaab Stories and the related Refugee News are two of the most elegant projects that have used the power of free social media tools (particularly Tumblr and YouTube) to help refugees publish stories. In these cases, professional filmmakers and refugees worked together to create ongoing social media coverage of the refugee camp for Somalians in Kenya.

Globally available and free technology platforms are helpful, but tools, platforms and projects are now emerging that are specifically aimed at refugees to allow them to self-organise and connect digitally.

Refunite is a social network designed to connect dispersed families that have low access to technology following displacement. It allows refugees to remain anonymous to everyone other than their family members, which aids those who may not be able to register with formal institutions because they are awaiting asylum decisions or are stateless. The platform currently reaches more than 500,000 refugees and is aiming to connect 1 million during 2015. It is geared towards low-end mobile technology to ensure that nearly anyone can use it. It can even be accessed using an interactive voice response system or text-messaging for those who are illiterate or don’t have internet access.

Low-cost and low-barrier-to-entry technologies such as these are proving to be a key part of connecting refugees in crisis. The UNHCR is telling the world the story of Jordan’s Zaatari camp via Twitter (which has claimed to be the first refugee camp with an official Twitter account). Nasreddine Touaibia, a UNHCR communications associate at the camp described how WhatsApp, a free or low-cost mobile messaging system, is being used by Syrian refugees to self-organise. “Urgent messages are sent to these groups and they are reflected in the Facebook group later. It’s their own emergency broadcast network,” he told Index, describing how WhatsApp had been used to give warnings when flooding occurred at the camp.

South African technology startup Vumi is now trying to build on this trend of using low-cost messaging services to create technical products that can empower refugees to self-organise at scale. Its platform uses mass mobile messaging and low-fi browsing to enable access to civic information.

Building on its success in Libya of technically enabling Wikipedia Zero (a Wikipedia Foundation project which gives access to Wikipedia without data charges in 35 countries) and distributing voter information, the company is now in the planning stages for a project focussed on empowering refugees, in partnership with South Africa’s Lawyers for Human Rights, an NGO that deals largely with refugees in South Africa.

Various NGOs and other services are also using social media to provide platforms that help refugees re-settle. These are largely regionally based and aim to help refugees understand the legal and social contexts they are in. In the UK, the Refugee Council and Bail for Immigration Detainees provide online resources and tools that help refugees build and understand their legal cases. Migrant Voice, another UK-based organisation, provides training and tools to allow migrants (including refugees) to publish and communicate their stories.

Refugees and migrants certainly benefit from the uses of social media that everyone with internet access does; but the emerging platforms in the space are where the traditional model of solitary, isolated migrants can be disrupted. Tools specifically tailored to the needs of the excluded have the potential to create the most significant change in a networked world.

To read other articles from the issue, subscribe to the magazine in print, iPad, or phone find out more here or on iTunes, search for “Index on Censorship”.

This article and photograph is part of Across the wires, the spring 2015 issue of Index on Censorship magazine, and should not be reproduced without permission of the magazine editor. Follow the magazine on @Index_magazine

© Jason DaPonte

6 Mar 2015 | Afghanistan, Asia and Pacific, mobile, News

Last year, authorities in the east of Afghanistan decided to shut down a cemetery. The problem was that this particular cemetery was not just a final resting place; it had taken on a second function as a marketplace where women in the city could meet and trade. With the closure, the financial lifeline the women had created for themselves, was cut. There were some protests, the story was covered in a local newspaper, and that was it.

Afghan media has experienced a significant growth spurt over the past years. In 2000, the country was home to 15 news outlets; in 2014 the figure was just shy of 1,000. Hidden within these numbers is another slowly expanding subcategory. Of around 12,000 working journalists in Afghanistan today, some 2,000–2,500 are women, up from an estimated 1,000 in 2006. The truly vital role these women play in Afghan society is too often overlooked.

In a country where traditional cultural norms still hold significant sway, strict limitations on contact between the sexes continue to be enforced in many areas. As a result, there are spaces only female journalists have access to, grievances only female journalists can be told and important realities of women’s lives that only female journalists can report on. Where women media workers are few and far between, such stories — like in the case of the cemetery closure — go underreported, or are buried entirely.

“Covering and focusing on women’s issues is always my favourite, and when I produce programs and make reports on these issues, I really like it and think I’ve done something important,” Radio Sahar Station Manager Humaira Habib told Index. Radio Sahar is part of Parwana (butterfly), a network of radio stations dotted around Afghanistan, which focuses on stories that impact women and their rights and needs. And from the managerial to the executive level, they are all-female operations.

Habib says she made the decision to go into journalism in 2002, and was influenced by the plight of women under the Taliban. “I thought journalism was a good tool to reach to all the aims and goals, and to solve the problems and challenges of women. I think media plays a very important role in informing citizens,” she explained. “This was the reason I decided to study journalism.”

But while the long view seems to suggest the number of Habib’s female compatriots will continue to grow, serious challenges and setbacks remain the reality in the shorter term.

Part of the problem is that the same traditional norms that make female journalist’s contribution especially valuable, still present a significant barrier to many women joining the media industry. As reporter Zarghona Salihi told Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, journalism is widely viewed as “immoral work” that carries with it social stigma for women.

“Parents don’t permit their daughters to become journalists [in particular] because female journalists soon turn popular and that puts them in lots of troubles,” news radio host Haseena Ahmadi told Voice of America.

Another, more direct and overt challenge is the seemingly worsening security situation for media workers in general, and the particular threats faced by women. Since 2001, 49 journalists have been killed, and attacks went up 64 per cent from 2013 to 2014, according to a recent report from Human Rights Watch. What’s more, they face a multi-pronged assault — from the government and local authorities, as well as from war lords and the Taliban. Meanwhile, impunity for such crimes persists.

Women must deal with all this, and then some. “Female journalists face particularly formidable challenges. Social and cultural restrictions limit their mobility in urban as well as rural areas, and increase their vulnerability to threats and attacks, including sexual violence,” the Human Rights Watch report states. Since 2010, three female journalists have been killed, including 26-year old Palwasha Tokhi, stabbed to death outside her house in September last year. The Afghan Journalists Safety Committee says that “dozens have been intimidated to stop working”. In 2013, Shaffiqa Habibi, director of the Afghan Women Journalist Union, estimated that 300 professional female journalists had stopped working due to safety concerns.

“The big challenge that journalists face here is the security problem. That really hurts us,” agrees Habib. In 2004 she was threatened by authorities and told she could never again work as a journalist in the western province of Herat. But she fought back, and today continues to hold a senior role at a radio station in that province. As one young journalist told International Media Support: “I have been threatened by the Taliban, corrupt authorities, warlords and even the government. But none of these threats will ever stop me from what I do.”

The struggle, however, doesn’t end by challenging traditions and braving a volatile security situation. Female journalists in Afghanistan are also facing a problem familiar to women all over the world: they’re simply not getting the chances their male counterparts are. On this point, international media has failed Afghanistan’s women reporters. While Amie Ferris-Rotman was working as Reuters’ Afghanistan correspondent, she realised that none of the foreign news outlets hired Afghan female correspondents, in any capacity.

“I found this hypocritical,” she told Index. “We put out a plethora of stories on women’s rights and the awful hurdles Afghan women face, yet we did not take the extra step to hear their stories in a professional context.”

Pointing to the continued prevalence of separation between the genders, she argues that by not giving a platform to female Afghan journalists, we are missing the full story. The journalists, meanwhile, are denied good networks and professional opportunities to further their careers. To help rectify this situation, Ferris-Rotman has set up the Sahar Speaks programme, to offer training and mentoring by peers from around the world to Afghan female journalists, with the aim of helping them produce stories to be published by international outlets. As she has written about the project: “Imagine how rich and nuanced the other side of the Afghan story can be, if told by its own women, not by Afghan men or foreign reporters.”

Abdul Mujeeb Khalvatgar, the director of media freedom advocacy group Nai, which is behind the Parwana network, believes it to be very important that Afghanistan’s female reporter pool continues to grow. Certain topics, he explains, are still considered by some to be taboo for men to cover. He mentions literacy rates among women, violations against women and how women are treated both in rural and urban areas as examples of stories that “raised the need of having women journalists to report”.

Habib stresses the importance of increasing the number of female reporters outside the bigger cities, where many women’s issues that male journalists have limited access to, go uncovered. This is a “serious problem” she says, adding that “we need to train girls from those places to at least learn basic journalism to cooperate with local and national media”.

Despite the challenges, Khalvatgar, who has been nominated for an Index award for his media freedom campaigning in Afghanistan, is confident that there is enthusiasm among women to work in the sector. He points to his experience of visiting journalism schools and seeing a higher number of female than male students, as one indicator. “There are a lot of hopes and wishes among women to become journalists,” he says.

Afghanistan’s President Ashraf Ghani vowed during his 2014 election campaign to uphold freedom of expression and protect journalists against abuse. Whether he will stick to his promise down the line, so the enthusiasm Khalvatgar speaks about can truly be harnessed, remains to be seen. What is clear, is that without more women feeling encouraged and safe enough to join Habib and her colleagues in their work, important stories will continue to go untold.

This article was posted on March 6, 2015 at indexoncensorship.org