Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”

يواجه الصحفيون في المكسيك تهديدات من حكومة فاسدة وكارتيلات المخدّرات العنيفة، كما أنهم لا يمكنهم دائما الوثوق ببعض زملائهم الصحفيين، يكتب دنكان تاكر

“][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

شارك المئات من المتظاهرين في مسيرة صامتة في عام ٢٠١٠ لإدانة أعمال القتل والخطف ضد الصحفيين في المكسيك, John S. and James L. Knight/Flickr

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”The big squeeze” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F12%2Fwhat-price-protest%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The spring 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at multi-directional squeezes on freedom of speech around the world.

Also in the issue: newly translated fiction from Karim Miské, columns from Spitting Image creator Roger Law and former UK attorney general Dominic Grieve, and a special focus on Poland.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”88803″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/12/what-price-protest/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Fifty years after 1968, the year of protests, increasing attacks on the right to assembly must be addressed says Rachael Jolley”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

A protester wears the Anonymous mask during a protest. Credit: Sean P. Anderson/Flickr

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”Protecting protest is vital, even if it doesn’t feel important today. ” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”91582″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228808534472″][vc_custom_heading text=”Uruguay 1968-88″ font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228808534472|||”][vc_column_text]June 1988

In 1968 she was a student and a political activist; in 1972 she was arrested, tortured and held for four years; then began the years of exile.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”94296″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228108533158″][vc_custom_heading text=”The girl athlete” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228108533158|||”][vc_column_text]February 1981

Unable to publish his work in Prague since the cultural freeze following the Soviet invasion in 1968, Ivan Klíma, has his short story published by Index. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”91220″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0306422017716062″][vc_custom_heading text=”Cement protesters” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422017716062|||”][vc_column_text]June 2017

Protesters casting their feet in concrete are grabbing attention in Indonesia and inspiring other communities to challenge the government using new tactics.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”What price protest?” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F12%2Fwhat-price-protest%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In homage to the 50th anniversary of 1968, the year the world took to the streets, the winter 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at all aspects related to protest.

With: Micah White, Ariel Dorfman, Robert McCrum[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”96747″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/12/what-price-protest/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Mexican journalist Javier Valdez who was recently shot and killed. Credit: Gobierno Cholula/Flickr

For years, Index on Censorship has covered stories of violence against the media in Mexico. In the first six months of 2017, seven journalists have been killed, a terrifying statistic. To help those researching media freedom in Mexico, we have compiled a reading list of articles from the past five years. It includes details of threats, punishments and pressures faced by Mexican journalists. Students and academics whose universities subscribe to Sage Journals will find all these articles free to read.

Making a killing: A special Index investigation looking at why Mexico is an increasingly deadly place to be a journalist as reporters face threats from corrupt police to deadly drug gangs

Vol 46, Issue 3, 2017

Ahead of Mexico’s elections next year, in a special investigation for Index, Duncan Tucker looks at threats to journalists over the past decade.

Read the full article here

Parallel lives and unparalleled risks: The author discusses his time reporting from Mexico, how the death of one journalist particularly affected him and introduces an excerpt from his forthcoming novel

Vol 46, Issue 3, 2017

Mexico is one of the most dangerous countries to be a reporter today, but these dangers are not spread evenly between local and foreign reporters. Author Tim MacGabhann speaks to Jemimah Steinfeld about why this is the backdrop to his new book and introduces an extract from it

Read the full article here

Documenting the truth: Documentaries are all the rage in Mexico, providing a truthful alternative to an often biased media

Vol 47, Issue 3, 2018

Documentaries are growing in popularity in Mexico, and have more freedom to broadcast facts and challenge government lies.

Read the full article here

Between a rock and a hard place: Mexico’s journalists face threats from cartels, the government and even each other

Vol 46, Issue 1, 2017

Alberto Escorcia and Javier Valdez discuss the pressures on Mexican media from all sides: drug cartels, government agencies, and even from other media outlets. These two reporters explain the difficulties journalists face and note that often there is little police protection from cartels. Valdez, a globally known journalist, was shot and killed in May 2017.

Read the full article here

Shooting from the hip: A new mayor in a Mexican border city believes he will make it less dangerous for journalists

Vol 46, Issue 1, 2017

Does local Mexican government have the ability or will to protect journalists? In an interview with Armando Cabada Alvídrez, the mayor of the largest city in Chihuahua (on the border of the United States), and Gabriela Minjares, a co-founder of the Juárez Journalists’ Network, Index on Censorship explores government promises and speculation from journalists on Mexico’s imminent potential for improvement of journalist security.

Read the full article here

Shooting the messengers: Women investigating sex trafficking in Mexico

Vol 45, Issue 2, 2016

Mexican journalists investigating sex trafficking, prostitution or child pornography often encounter threats and pressure not to cover stories. Journalists Lydia Cacho, Sanjuana Martínez and Shaila Rosagel discuss the retaliation they faced for uncovering unsavoury relationships between sex crimes and government officials.

Read the full article here

Mexican airwaves: Interviews with radio journalists who were shut down after investigating presidental property deals

Vol 44, Issue 4, 2015

“The level of violence against Mexican journalists has been well documented, but comparatively little is known about the pressures that reporters and their bosses come under when dealing with the government.” Carmen Aristegui, one of Mexico’s most renowned journalists, lost her job and ability to report in Mexico after uncovering allegations of property fraud against President Peña Nieto.

Read the full article here

Mexican stand-off

Vol 44, Issue 2, 2015

Since the abduction of 43 missing students from Ayotzinapa training college, tensions between Mexico’s academic institutions and government have been at an all time high. In this article, Dr Rossana Reguillo Cruz discusses the case of the missing students, along with the threats she receives on a daily basis after discussing her support for investigations into their disappearance.

Read the full article here

Constitutionally challenged: Mexico’s struggle with state power

Vol 43, Issue 4, 2014

In addition to threats and cover-ups, Mexican journalists face increasing pressure from other directions. While much censorship occurs without regard to the law, this article explores how suppression of speech is becoming further integrated into Mexican society.

Read the full article here

On the ground: In Mexico City

Vol 42, Issue 2, 2013

The Mexican office of Article 19 (the right to freedom of expression), has documented 900 incidents of suppressed expression, aided 100 targeted journalists and received dozens of threats since 2006 (as this article went to press). Ricardo Gonzalez discusses the challenges and progress of the Article 19 office in the face of increasing crime against journalists, and his hope for justice.

Read the full article here

Murder In Mexico

Vol 41, Issue 2, 2012

The Olympic Games frequently draw attention to the social and political conditions of their host countries, stirring up protests from the people and censorship from the government. Brian Glanville, originally a sports reporter sent to cover the 1968 Olympics, recounts his experience of media manipulation and student massacres by the Mexican government during the games, explaining the immense importance of international media coverage when local governments cannot be held accountable.

Read the full article here

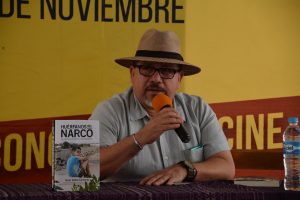

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”89329″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center”][vc_custom_heading text=”Mexico-based journalist DUNCAN TUCKER writes in the spring 2017 issue on reporting in a country where news is not just repressed, it’s fabricated, and journalists face violent threats from police and cartels. ” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”89160″ img_size=”213×300″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0306422011399687″][vc_custom_heading text=”Narco tales” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422011399687|||”][vc_column_text]March 2011

Bloggers and citizen journalists are telling the stories that the mainstream Mexican media no longer dares to report, says Ana Arana.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”89168″ img_size=”213×300″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064220902734319″][vc_custom_heading text=”Wall of silence” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064220902734319|||”][vc_column_text]February 2009

Analysis of the culture of intimidation facing investigative journalists in Mexico — from attacks on reporters to criminal activity.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”94760″ img_size=”213×300″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064227608532576″][vc_custom_heading text=”Guessing game” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064227608532576|||”][vc_column_text]April 1983

The unpredictability of Mexican government crackdown keeps the press guessing, making them careful with what they publish. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”The Big Squeeze” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fmagazine|||”][vc_column_text]The spring 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at multi-directional squeezes on freedom of speech around the world.

Also in the issue: newly translated fiction from Karim Miské, columns from Spitting Image creator Roger Law and former UK attorney general Dominic Grieve, and a special focus on Poland.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”88788″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/magazine”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]