Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Mikhail Gorbachev in 2008. The former president of the Soviet Union passed away on 30 August. Credit: European Parliament

In every field there are people who become living legends, people who inspire their colleagues and shape their chosen field. They add to our collective knowledge, they shape the world we live in and their contributions ensure that we both question the status-quo and think again about our individual and collective core values.

Sometimes these people reach further than their own fields. Sometimes they inspire or challenge the world. Whether as thinkers, writers or leaders. Sometimes their experiences and their contributions come to define an era of history – for some maybe even just one year.

1989. A year of deep turmoil. A year that reshaped the world. A year that defined the next generation. A year of both hope and horror. And on a personal level, a year that defined the type of world that I was going to live in.

1989 saw the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Tiananmen Square protests, the Velvet Revolution, the Hillsborough disaster, the Exxon Valdez spill, Solidarity was elected in Poland, FW de Klerk was elected in South Africa, Sky TV was launched and the Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa against Salman Rushdie. In different ways each of these events shaped the world we live in today – 33 years later.

I often write that there has been too much news. Too many issues for the Index team to cover. Too many crises. In 1989 we published nine editions of the magazine, to keep up with the news and to ensure that voices of dissidents were being heard, as authoritarian regimes began to fall.

In the last month I have found myself thinking a great deal about the events of 1989 and what they led to. The path of history that was chosen on those pivotal days and the actions of our leaders whose immediate responses to these events had long-term consequences. Whilst there are many global figures who dominated the news during my childhood, two of them have this month caused me to pause and consider what the world would have been like if they hadn’t been brave enough to challenge the status quo.

Sir Salman Rushdie and Mikhail Gorbachev.

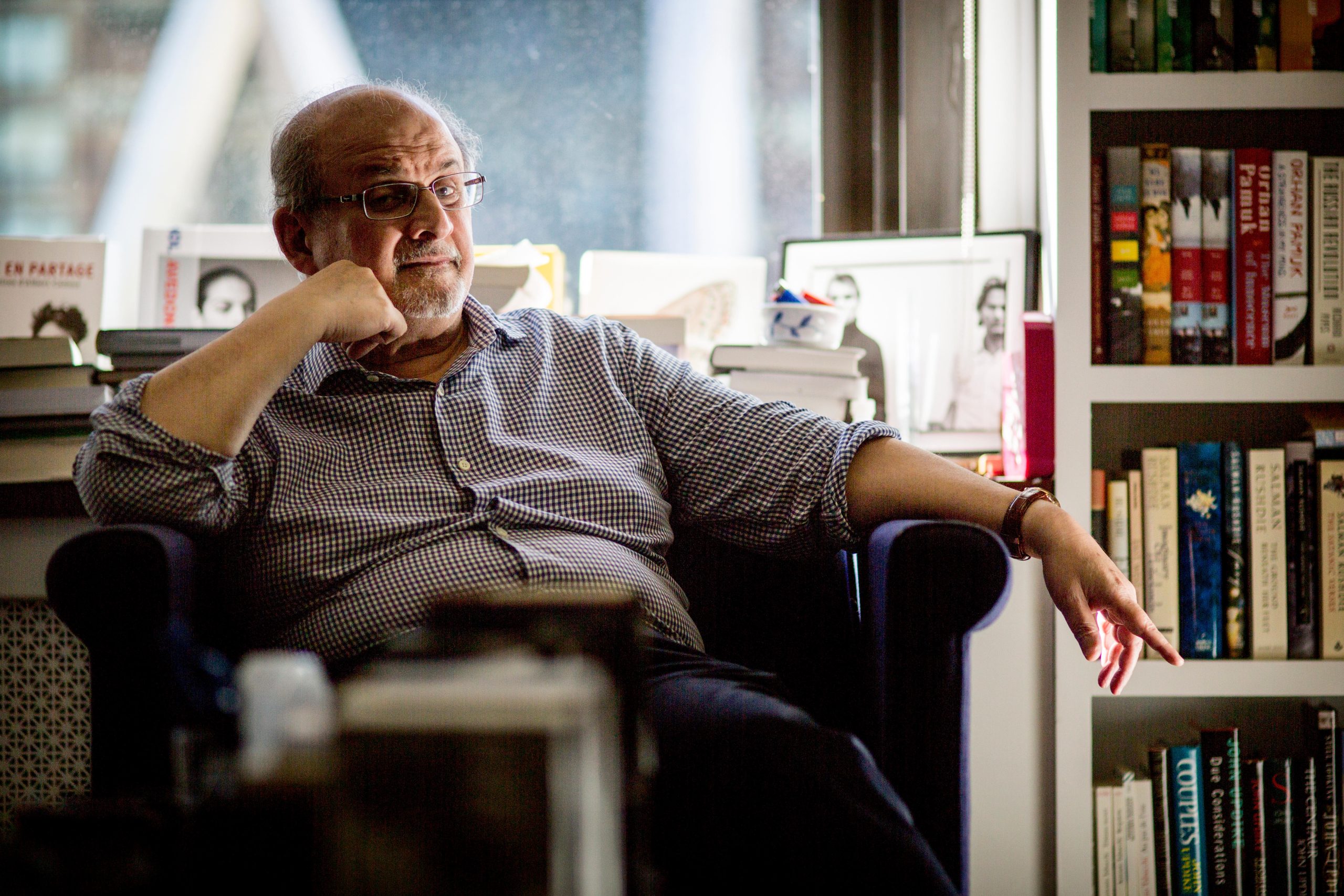

Salman Rushdie pictured in New York in 2016. Credit: Orjan Ellingvag/Alamy

Every day since the horrendous attack on Sir Salman, last month, Index has received messages of support for him as he recovers from his injuries. The messages have been touching, political and occasionally controversial – just like his writings! What they have demonstrated is regardless of people’s associations with him and their feelings towards him, his bravery and commitment to the values of freedom of expression in the face of the gravest of threats inspired a generation.

For over three decades he has refused to be intimidated, to be cowed. He continued to write, to speak and stay true to his values. He embodies the fight of the dissident, the determination to be heard and the power of words. He has shaped my approach to the world we live in and more importantly he has provided a role model for all of those that Index seeks to support and promote every day. I am so pleased that those who sought to assassinate him failed and we still have him amongst us.

In a different way Mikhail Gorbachev is just as fundamental to the history of Index. I’m not sure that Michael Scammell, the first editor of Index, would have believed that within a decade of Gorbachev’s coming to power in the USSR his writing would be in Index. His bravery in embracing glasnost provided hope for a generation.

The fall of the Berlin Wall without military repercussions provided hope of a peaceful transition to democracy – not just in central and eastern Europe but throughout the world.

This isn’t to say he wasn’t flawed. He was and his actions in the Baltics and the Caucuses were as expected from an authoritarian leader, and his support for the 2014 annexation of Crimea will forever tarnish his legacy.

But… Index was founded to provide a platform for samizdat, to provide a voice for dissidents who lived behind the Iron Curtain, to campaign for the right to freedom of expression both in the USSR and around the world. His bravery in embracing glasnost provided space for people to speak freely, to write and to be heard, even if Putin once again has shut the door. Gorbachev enabled people to get a taste of what they were missing. We can only hope that in the long arch of history glasnost will win out.

Mikhail Gorbachev in 2008. Photo: European Parliament, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

In 2000 Mikhail Gorbachev wrote a short piece for Index on Censorship about the dangers to free expression in 21st century Russia. It followed raids carried out by masked, armed police on the offices of the Media-MOST consortium, then one of the most powerful media organisations in Russia. It was a show of force by the incoming president, Vladimir Putin, and a chilling sign of things to come.

The article, entitled Citizens’ Watch, expressed the best of the former President’s instincts in support of democracy and freedom: “Without a free press people don’t have a voice. They can be used as the authorities see fit; they can be manipulated”.

It was also prophetic in its concerns that the Russian people were sleepwalking into an authoritarian disaster: “I’m… worried and dispirited by the apathy of the public. The journalists are having to defend themselves on their own. It’s time we understood we shall never be a democratic state until we have learned to be citizens.”

He concluded: “It is not easy to live as a free man; without democratic institutions and rules, freedom often becomes its opposite.”

But the piece also demonstrates Gorbachev’s fatal weakness. As a good man with good intentions, he was too willing to give those with bad intentions (such as Vladimir Putin) the benefit of the doubt. Musing on who might be ultimately responsible for the crackdown, he wrote: “I find it hard to believe that raids like these can take place with the president’s knowledge. If, indeed, it is with his knowledge, I personally feel very disappointed.”

Disappointment defined Mikhail Gorbachev. As the last leader of the Soviet Union, he was quite possibly the most influential political figure of the post-war period, but from the moment the Berlin Wall fell, his life was marked with a series of disappointments. He had hoped the break-up of the Soviet Union would lead to democratic transformation and the introduction of a market economy with social safeguards. In many countries of the former Eastern bloc, this was indeed the case, but he also witnessed the rise of tyranny and corruption in many of the former Soviet republics. In his beloved Russia itself, he saw his liberal economic reforms hijacked first by the oligarchs and then by the state itself. This man of peace, whose childhood had driven him towards dialogue with the West, stood by as his country descended into an increasingly aggressive foreign policy with wars in Chechnya, Georgia, Syria and latterly in Ukraine. History will judge him harshly for his support of the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014, although in his mind it was consistent with his lifelong support for national self-determination.

But possibly his greatest disappointment was what he saw as the catastrophic failure of world leaders to deal with the environmental crisis. In an interview with the Russian publication Dos’e na Tesnzuru reprinted in this magazine in 1998 he noted that “ecology” sprang to the top of the agenda in Russia thanks to his policy of glasnost (openness). As a result, 1,300 polluting enterprises were closed. It was his dream to establish a global environmental organisation to address the combined challenges of security poverty and environmental destruction and following the Rio Earth Summit in 1992 he established Green Cross International in Geneva.

His words in Index sounded an important warning: “Everyone can see that the forests are retreating, rivers becoming polluted. The reasons are obvious – people rule the earth, but they are not looking after it, only making demands: give me cotton, give me wood, give, give, give. We have to manage things differently.”

The end of the Cold War was Gorbachev’s greatest legacy and he knew that the freedoms he helped establish were built on the work done by the dissident intellectuals that came before him. He also knew that complacency was not an option.

A quarter of a century ago he told Dos’e na Tesnuru (which means Index on Censorship in Russian): “I am not a pessimist. All over the world the last dictators are leaving the political scene; attempts to impose dictatorship are ridiculous. Only one thing can protect us from such attempts – freedom of speech. That’s why any defence of freedom of speech is so important. Without it we could find ourselves once again caught in the trap.” His prediction of the demise of dictatorships was perhaps premature, but he was never wrong about the antidote.

Credit: Amy Allcock / Flickr

The summer 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores how the 1917 Russian Revolution still affects freedom today, in Russia and throughout the world.

To mark the release of the issue, Index has compiled a reading list for people wishing to learn more about its legacy in the world today. This list includes works from Soviet Russia and post-Soviet Russia, including Russia under Putin today.

Alexander Solzhenitsyn, God keep me from going mad*

1972; vol 1, 2: pp.149-151

An excerpt of a longer poem written by Solzhenitsyn while in a labour camp in North Kazakhstan. The camp later became the inspiration for Solzhenitsyn’s novel A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich.

Alexander Glezer, Soviet “unofficial” art*

1975; vol 4, 4: pp. 35-40

Glezer was responsible for organising the now famous unofficial art exhibitions in Moscow in 1974. The first exhibition, on 15 September, was ‘”bulldozed” by police and KGB agents, and a number of artists who tried to exhibit their work were arrested. Two weeks later, however, an open-air exhibition did take place, after the authorities gave permission, and some 10,000 people turned up to see paintings and sculptures by modern Soviet artists who did not enjoy official favour.

Michael Glenny, Orwell’s 1984 through Soviet eyes*

1984; vol 13, 4: pp. 15-17

This article examines Soviet interpretations of 1984, including the assertion that George Orwell was actually critiquing capitalism, not the USSR, with his novel.

Natalya Rubinstein, A people’s artist: Vladimir Vysotsky

1986; vol 15, 7: pp. 20-23

This is an article about the musician Vladimir Vysotsky, once called “the most idolised figure in the Soviet Union”. His songs were circulated on homemade tapes, though never officially recorded until after his death.

Irena Maryniak, The sad and unheroic story of the Soviet soldier’s life

1989; vol 18, 10: pp. 10-13

An Estonian reporter’s exposé prompts a call from the army. Madis Jurgen, who brought to light the dark side of the Soviet armed forces, left Tallinn on Friday 13 October, bound for New York and Toronto, from where he decided to await events.

Svetlana Aleksiyevich, A Prayer for Chernobyl

1998; vol 27, 1: pp. 120-128

Early on 26 April 1986, a series of explosions destroyed the nuclear reactor and building of the fourth power generator unit of Chernobyl atomic power station. These extracts are not about the Chernobyl disaster but about a world of Chernobyl of which we know almost nothing. They are the unwritten history.

Viktor Shenderovich, Tales from Hoffman*

2008; vol 37, 1: pp. 49-57

As they say, still waters run deep. On 8 February 2000, an announcement was made in the St Petersburg Gazette by members of the St Petersburg State University Initiative Group. Shortly beforehand they had, in competition with others, nominated Putin as a presidential candidate and now wished to demonstrate their enthusiasm for their former pupil. What they published was a denunciation.

Fatima Tlisova, Nothing personal

2008; vol 37, 1: pp. 36-46

Fatima Tlisova was brutally beaten for her uncompromising journalism on the North Caucasus. Here, she recounts the tactics used to intimidate her.

Anna Politkovskaya, The cadet affair: the disappeared

2010; vol. 39, 4: pp. 209-210.

An article on the disappeared in Chechnya, who officially number about 1,000, but unofficially are almost 2,000. They disappeared throughout the war. The author, Anna Politkovskaya, was murdered in her Moscow apartment in a contract killing in 2006.

Nick Sturdee, Russia’s Robin Hood*

2011; vol 40, 3: pp. 89-102

Widespread frustration with the establishment has fostered a brand of political street art that is taking the country by storm.

Ali Kamalov, Murder in Dagestan

2012; vol 41, 2: 31-37

Ali Kamalov, the head of Dagestan’s journalists’ union fears for the future of press freedom following the murder of the country’s most prominent editor. On 15 December 2011, Hadjimurad Kamalov was murdered in Makhachkala, the seaboard capital of Dagestan.

Maxim Efimov, Religion and power in Russia

2012; vol 41, 4

Although the Russian constitution enshrines freedom of expression, the authorities routinely clamp down on anybody who treasures this fundamental right. State officials, judges, deputies, prosecutors and police officers serve the ruling regime and control society, rather than defend the constitution or protect human rights.

Elena Vlasenko, From perestroika to persecution

2013; vol 42, 2: pp. 74-76

Elena Vlasenko covers wavering hopes for an open Russia, and the evolution of repressive legislation, state censorship and journalists under threat.

Helen Womack, Making waves

2014; vol 43, 3: pp. 39-41

Helen Womack interviews the founder of the last free radio station in Putin’s Russia. These men are not dissidents, just journalists dedicated to professional principles of objectivity and balance. But in Putin’s Russia, where almost all the media spout state propaganda, that position looks like radical nonconformity, and it seems a wonder that Echo survives.

Andrei Aliaksandrau, Brave new war*

2014; vol 43, 4: 56-60

In the winter 2014 issue of Index on Censorship magazine, Andrei Aliaksandrau investigates the new information war between Russia and Ukraine as he travels across the latter country.

Andrei Aliaksandrau, We lost journalism in Russia

2015; vol 44, 3: pp. 32-35

Andrei Aliaksandrau examines the evolution of censorship in Russia, from Soviet institutions to today’s blend of influence and pressure, including the assassination of journalists.

Andrey Arkhangelsky, Murder in Moscow: Anna’s legacy*

2016; vol. 45, 3: pp. 69-74.

Andrey Arkhangelsky explores Russian journalism a decade on from Anna Politkovskaya’s murder and argues that the press still struggles to offer readers the full picture.

*Articles which are free to read on Sage. All other articles are available via Sage in most university libraries. To find out more about subscribing to the magazine in print or digitally, click here.

Is the Evening Standard headed for the same fate as Alexander Lebedev’s under-resourced Russian newspaper, Novaya Gazeta? Andrei Soldatov reports

Is the Evening Standard headed for the same fate as Alexander Lebedev’s under-resourced Russian newspaper, Novaya Gazeta? Andrei Soldatov reports

(more…)