Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

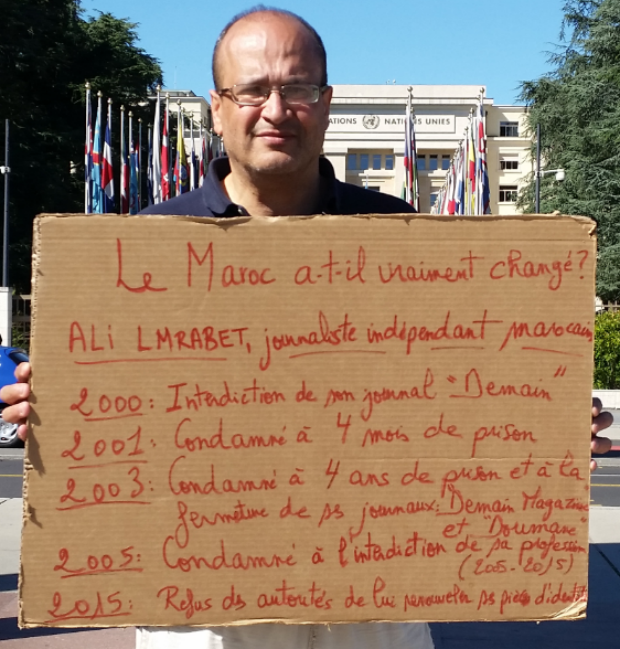

Ali Lmrabet is on hunger strike outside the UN building in Geneva (Photo: alisinpapeles.blogspot.com.es)

Outside the United Nations building in Geneva, Switzerland, Ali Lmrabet is in his 28th day of a hunger strike. The journalist and satirist is protesting what he sees as the latest bid from his country Morocco to stop him from doing his job.

In a period spanning over a decade, Lmrabet, who was the editor of two satirical publications, has continuously been targeted by Moroccan authorities. In 2003, he was jailed for reporting on personal and financial affairs of Morocco’s King Mohammed VI. His magazine Demain was banned. Though initially handed down a three-year sentence, Lmrabet was released after six months. But his troubles were far from from over: in 2005, he was banned from practising journalism in his home country for ten years, over comments made about the dispute in Western Sahara between Morocco and the Algerian-backed Polisario Front.

Now authorities are seemingly using bureaucracy as a tool to try and silence Lmrabet again. As his ban expired in April this year, he returned to Morocco with the aim of relaunching Demain. But there he was denied a residency permit, without which he is unable to set up the magazine. In a further complication, he also needs the residence permit to renew his passport. When this expired on 24 June, Lmrabet, who was in Geneva to participate in a session of the UN Human Rights Council, decided to start a hunger strike.

“He is very tired,” his partner Laura Feliu told Index on Censorship in a phone interview. She explained how the heat in Geneva has played a part in leaving Lmrabet drained of energy, and while he hasn’t had any serious health problems, he is experiencing sensations of seasickness.

Lmrabet’s protest takes place outside the UN offices, though a heatwave forced him to move inside on Sunday. He sleeps in a Protestant church near the centre of the city. Subsisting on water and some sugar and salt, he has lost at least seven kilograms since the start of the strike.

“He started a hunger strike to protest because he has been denied the right to work as a journalist,” Feliu explained. But in addition to having his free expression and press freedom curtailed, he also has another problem, she adds: “He is denied his right to an identity.”

Lmrabet has support in his country. Some 100 well-known Moroccans from the worlds of media, human rights and academia have signed a petition to the government calling on him to be allowed to renew his documents and continue his work in journalism. Independent and prominent human rights organisations in Morocco are also backing him, according to Feliu.

The response from Moroccan authorities, meanwhile, has so far been unsympathetic. The country’s UN ambassador Mohamed Aujjar has urged Lmrabet to contest what he labelled an “administrative decision” in Morocco, telling AFP that “you don’t get your papers by staging a hunger strike”. Lmrabet, on his part, is unwilling to risk being stranded in Morocco without papers and the ability to work or leave the country. “No one trusts the judical system in Morocco,” he said.

Feliu says it’s difficult to know what the outcome will be, but that Lmrabet is convinced this is the only way to protest. And he remains hopeful.

“He is very convinced of his fight. He is very convinced of his cause. He says that he has the moral to do it.”

Join us 30 July at Stand Up for Satire, a fundraiser in support of Index on Censorship.

This article was posted on 21 July 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

Index on Censorship is one of 21 members of the Arts Rights Justice network who have signed the following statement:

Index on Censorship is one of 21 members of the Arts Rights Justice network who have signed the following statement:

Two representations of a theatre performance entitled “b7al b7al”, 4 and 5 July 2015 in Tangiers, Morocco have been forbidden again following a similar incident in Rabat on 13 June. Although the organisers had fully respected all administrative procedures, they were informed on 4 July (15 minutes before the performance after all technical installations had been prepared and the actors were ready), that the performance couldn’t take place. The second representation the following day was also forbidden.

This ban takes place at a time when the migrant communities of the city of Tangiers are living violent, racist events that represent a complete denial of basic human rights and values.

The performance b7al b7al relieves tension and strengthens dialogue regarding migration between Morocco and Sub-Saharian Africa. It is regrettable that such a performance be forbidden. It offers a place for migrants from Sub-Saharian regions to express themselves, and to make the public aware of the problems they face. It also helps prevent stereotypes and prejudices linked to racism.

The public space should be accessible to cultural actors, artists and organisations representing civil society and should be free of constraints. It is here that art gets closer to citizens, allowing for debates to take place openly on highly relevant issues for society.

Public authorities’ role is to facilitate access and insure security of artists and citizens, respecting the freedom of artistic expression guaranteed by the Moroccan Constitution.

B7al b7al is part of Mix City, a project of Association Racines, in partnership with Theatre of the Oppressed in Casablanca and Minority Globe, also in collaboration with the association Visa Without Frontiers,Tangiers. Mix City is part of “Diversity, Drama and Development” co-funded by the European Commission in the framework of Medculture, also supported by the Prince Claus Fund for Culture and Development, the Swedish Foundation and the Heinrich Böll Foundation. It was set up by Minority Rights Group International, Civic Forum Institute and Andalus Institute.

Police blocked access to the concert venue by closing down the streets around it. (Photos: Mari Shibata for Index on Censorship)

A former Index Youth Advisory Board member travelled to Casablanca to see Moroccan rapper El Haqed’s first concert in the country. This is her account of the police crackdown that silenced the 19 June performance.

I had travelled nine hours for a concert that the Moroccan state did not want its people to see.

“This is going to be the first time I will have concert here, where I am from,” rapper Mouad “El Haqed” Belghouat told me ahead of the scuttled 19 June show at The Uzine, a Casablanca concert venue and cultural centre supported by the Touria and Abdelaziz Tazi Foundation.

“I’ve been preparing for this moment for a week. There have been jam sessions every day to make this the very best show.”

Belghouat, who won the Index on Censorship Award for Arts in March, is known as El Haqed, roughly translated as The Enraged in English. His music, which describes Morocco’s corruption and social injustice, is driven by the Arab Spring that sparked Casablanca’s pro-democracy February 20 movement.

Having been imprisoned several times since 2011 – during which he went on hunger strike for what he calls “appalling conditions” – he has regularly been silenced by officials. El Haqed has been limited to distributing his music on YouTube and sharing updates on Facebook, where he has an avid fan base of over 43,000.

Winning the Index arts award led to opportunities for El Haqed to perform in other European countries. In May he performed in Oslo. Fans back in Morocco were eagerly awaiting the chance to see him live. His planned concert drew people from around the country.

“I have come all the way from the capital city of Rabat to see Mouad’s first concert in Morocco,” said Hamza, a 22-year old LGBT activist, who declined to provide a last name. “I made sure I got here early, and catch up with everyone I know who has been involved in the February 20 movement where Mouad’s songs were our anthems.”

Just moments after his band Oukacha Family began their sound check and testing the stage lights, word came from the front of house that police had gathered outside. Someone had also been arrested as they tried to enter the building to see the concert.

“My friends and fans outside are telling me the police are growing in numbers and are blocking the street,” El Haqed said as his phone continued to ring. “Those who organised this concert are also informing me that the police are threatening me to stop this from happening.”

As the band began its sound check, word came of the police presence outside.

The atmosphere suddenly became tense. The 20 or so people already inside the five-storey building were at risk of arrest. Most of them had been inside since the early afternoon to study whilst fasting for Ramadan, and to pursue their creative interests in the practice rooms and artistic spaces.

As the calls kept flooding in with updates, Mouad instructed everyone to wait in the back yard as a way of occupying the building without being identified by the police, who were able to see through the glass windows of the well-lit front entrance.

In the midst of the confusion, it was at times difficult to identify who could be trusted. Local journalists who arrived at the scene were blocked from entering the street and could not get near the building. As the only non-Moroccan inside, I was being asked with suspicion whether I was from media; getting out a visible video camera was now a definite no-go zone.

“When will officials stop interfering in what we want to do?” sighed Hamza. “This space is so special, it is the only place where young people can express themselves, with the support to explore their creative interests. It is the first space of its kind in Casablanca, where artists can host exhibitions and concerts freely.”

Once Mouad and a handful of key activists located a route around the building that avoided the light, we climbed several flights of stairs to the top floor, crawling along the floor towards a dark room where we could finally inspect what was going on outside. The sight was a shock for everyone, we felt trapped inside the building.

To get images without them spotting us meant flash was off, or hands over any light that was coming out of our phones.

Security officials crowded both the building and the street, ensuring the streets were empty by stopping vehicles coming through. This meant it was now easier for them to identify anybody who caught their eye.

Saja, another El Haqued fan, said she was excited to come and support his first concert in Morocco, but was turned away by police. “As I drove towards the venue, I was stopped by the gas station at the corner of the street and was just told to move. We had no chance to explain ourselves or ask questions, everyone was simply told that the street was closed and therefore weren’t allowed to enter.”

Then we saw officials arriving to cut electricity to the centre. We quickly took the lift downstairs, as Mouad figured that there would be no concert tonight. “This is it,” he said, “we can’t do anything without electricity – we have no power for the microphones, the speakers, or the lights on stage.”

Minutes before the electricity was cut, Mouad tried to upload some pictures to Facebook about what was happening, but failed. With the electricity cut, the wifi signal faded.

According to Moroccan press reports, police said that the building, which has hosted several concerts since it opened six months ago, was not up to safety codes, an allegation the centre’s management disputes. Contrary to the claims, the building is equipped with solar panels that provided the building with a small amount of light during emergency situations.

While waiting for news on what was going to happen next, Hamza had realised how lucky we were to have just missed the security officials arriving. “Imagine if they had arrived while we were out breaking fast eating!” he said. “That would have been really brutal, as we would also be left hungry and thirsty on top of all this stress.”

The decision was taken to leave the building at the instruction of the venue’s organisers. Once we managed to bypass the security without getting arrested, journalists who were barred from entering the street crowded around El Haqed to ask him what happened.

Once outside, El Haqed spoke to local media.

After we drove away from the area in a friend’s car, El Haqed told me that, “despite everything that happened, I feel strong”.

“I think that the government has a reason to bring police to the scene. Their action means my music is strong and is a threat to them. The incident makes me hurt and disappointed but I know I should keep going.”

And supporters like Saja have his back. “Mouad’s music speaks to the poor, those who are struggling and have nothing,” she says. “The cancellation of his first planned concert in Morocco is only going to fuel the desire to hear more from him.”

This article was posted on June 25 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

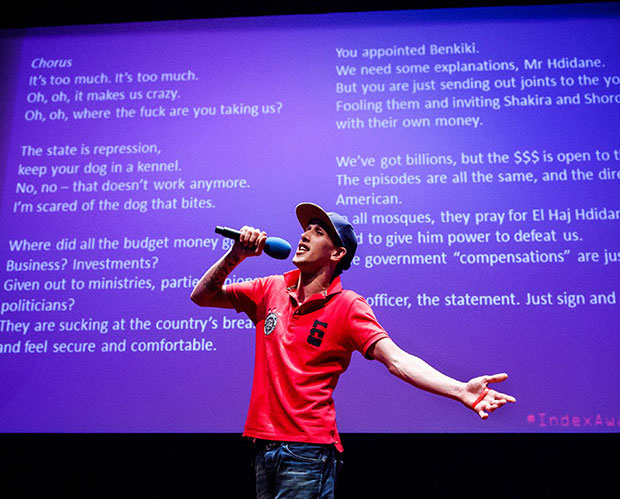

Moroccan rapper El Haqed performed in London at the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards in March 2015 (Photo: Alex Brenner for Index on Censorship)

Moroccan police prevented a planned 19 June 2015 concert by rapper Mouad “El Haqed” Belghouat, who was named the Index on Censorship Arts award winner in March 2015.

“The continued harassment of Mouad Belghouat, aka El Haqed, by Moroccan authorities must end. This latest silencing of Belghouat is another black mark for Morocco. We call on the government to allow Belghouat and other artists to be allowed to perform freely in the country,” Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg said.

On the evening of the concert, security officials blocked streets around The Uzine, a concert venue and cultural centre supported by the Touria and Abdelaziz Tazi Foundation. At the same time, officials cut electricity to the centre. According to Moroccan press reports, police said that the building, which has hosted several concerts since it opened six months ago, was not up to safety codes, an allegation the centre’s management disputes.

Belghouat releases music under the moniker El Haqed, roughly translated as The Enraged. His lyrics describe widespread poverty and endemic government corruption in Morocco. His song Stop the Silence became popular as Moroccans took to the streets in 2011 to protest against their government. He has been imprisoned on spurious charges three times in as many years, most recently for four months in 2014.

• El Haqed: I will fight for freedom, equality and human rights for ever

• #IndexAwards2015: Arts nominee Mouad “El Haqed” Belghouat