Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

US president Donald Trump’s executive order banning citizens of seven predominantly Muslim countries from travelling to the USA for has had devastating consequences for thousands of people. Among them is Index on Censorship Award winner Murad Subay. The Yemeni street artist is now unable to visit his wife, who is currently studying in the USA.

“It’s really frustrating to even start thinking that I won’t be able to see her for that long,” he told Index. “She was supposed to visit during summer break, however, it seems that she can’t do that now.”

With uncertainty surrounding how the Trump administration’s policy towards Yemen will play out, the couple are now facing the very real prospect of not seeing each other until she finishes her studies four years from now.

“It’s been a really difficult time for both of us because it’s the first time we’ve been away from each other for more than a month,” Subay said. “I can’t say that this doesn’t have its negative effects on my work, for it surely does.”

At home, the worries that have plagued Subay throughout the Obama administration remain, particularly Trump’s continuation – and possible escalation – of his predecessor’s drone strikes in Yemen, which by February 2016 had killed up to 729 Yemenis including 100 civilians. One rural counter-terrorism raid authorised by Trump has already left at least 10 women and children dead, according to Al-Jazeera.

2016 Freedom of Expression Fellow Murad SubayMurad Subay is the 2016 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Arts Award-winner and fellow. His practice involves Yemenis in creating murals that protest the country’s civil war. Read more about Subay’s work. |

“Trump has no right to make things even worse for Yemenis. Yemen is already suffering from US arms deals with Saudi Arabia that helped fuel this war. Barring Yemenis from entering the USA under his administration only adds to these troubles.”

The war has been hitting close to home for Subay in recent months. Two of his cousins were recruited by warring parties and killed on the battlefield. – Fuad Subay, aged 26, was a soldier killed in Albuka’a, and Yaser Subay, just 14, was recruited by Houthis and killed in Isilan.

On top of this, a close friend of his, the respected investigative journalist Mohammed Alabsi, was killed in an apparent assassination. According to the Yemen Times, Alabsi had gone out for dinner in Sana’a with a cousin on 20 December. A little while later both men were rushed to hospital, where Alabsi died.

“I was told that blood came out of his ears and eyes,” Subay said. “Mohammed was investigating the black markets trading in oil that were associated with high-ranking politicians. I do not know the exact details of this, but what I do know is that Yemen has lost one of its most important and noblest investigative journalists, and that I lost a dear friend.”

An investigation into Alabsi’s death is underway.

Subay addressed a recent wave of violence against civilians, including journalists and public figures, in a mural entitled Assassination’s Eye, painted on the Mathbah Bridge in Sana’a in late December. Part of the Ruins Campaign, the minimalist painting depicts a sniper’s crosshairs training in on a human target.

“It conveys the assassin’s point of view, where it first feels like it is only a part of training on how to hit a target, but then in the final square the bullet ends up in the head of a real person rather than a target board,” Subay explained. “These assassinations have spread vastly since 2012, where they were mostly carried out among the military ranks and politicians. Lately, however, these operations have been targeting civilians too. I was planning to address this issue some time ago after hearing about the assassinations of innocent civilians in different places of the country, and that was just two weeks before I was shocked by the death of my friend.”

Elsewhere, Subay has been asked to serve as a judge for the Italian arts award, Fax for Peace, which invites students and artists from around the world to send pictures, videos or animations on the themes of peace, tolerance, human rights and the fight against all forms of racism. He said of the role: “It is a great pleasure to be selected as a judge in this contest and it is a big responsibility, which I hope to be able to carry out effectively.”

However, with Yemen’s economic circumstances ever worsening, and many working people now into their fourth month without receiving salaries, he sees difficult times ahead.

“It’s very harsh to see people every day looking for anything to eat from garbage, waiting along with children in rows to get water from the public containers in the streets, or the ever increasing number of beggars in the streets. They are exhausted, as if it’s not enough that they had to go through all of the ugliness brought upon them by the war.”

Referring to the deaths of his cousins and his close friend, he added: “No one can live in this country and not be affected by the war. This all happened in the last three or four months. These events make a month in Yemen feel like a year.”[/vc_column_text][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1486138786513-e5ca059b-efd0-1″ taxonomies=”8196″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Credit: Ruins campaign. Bani Waleed, September 2016

On 3 September 2016, a group of Houthi rebels convened a meeting at al-Najah School in the al-Haima district of Bani Waleed, a local witness told Murad Subay, street artist and winner of the 2016 Index on Censorship award for arts, that the men entered the school without permission.

“We are not with any of the warring parties – we are caught in the middle,” the witness said.

Soon after, the school was destroyed in an airstrike carried out by the Saudi Arabian-led military coalition, killing one disabled student and adding 1,200 to the more than 3.4 million already forced out of education in the country as over 3,600 schools have been forced to close in the course of the war.

“Can you imagine? These are the soldiers of the wars to come,” Subay told Index. “Without education, these children could become tomorrow’s fighters and tools in the hands of extremists.”

At dawn on 4 September Subay travelled to Bani Waleed to create a mural on what remained of al-Najah.

Credit: Ruins campaign. Bani Waleed, September 2016

“When we got there I asked some of the students what they were going to do now that their school was destroyed and some told me they will go to Sanaa while others said they will travel to surrounding villages,” Subay said. “But it will be much more difficult for the 400 girls who attended the school because traditions in Yemen mean they will not be able to travel alone, making it impossible for them to go to other villages to study.”

2016 Freedom of Expression Fellow Murad SubayMurad Subay is the 2016 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Arts Award-winner and fellow. His practice involves Yemenis in creating murals that protest the country’s civil war. Read more about Subay’s work. |

Destroying schools isn’t a big deal for the warring parties, the artist added. “Some of the children of those leaders who shout ‘death to America’ are studying at the best universities in the world, including in the USA, while each bombed school in Yemen – especially big ones like al-Haima – will take years to rebuild.”

The situation is made even more difficult in a time of war when resources and building materials are almost impossible to come by. “Even if the West stopped supplying weapons to Saudi Arabia today and patted themselves on the back saying ‘we are doing good’, Saudi Arabia already has enough to wage wars for another 150 years if it wants.”

If there is any hope for peace to prevail and schools, hospitals and other buildings belonging to the people are to be rebuilt, countries like Britain and America should take a step further and tell Saudi Arabia “to show restraint”, Subay said.

“While Saudi Arabia is doing the majority of the destruction, all sides of the war in Yemen must take responsibility.”

Credit: Ruins campaign. Bani Waleed, September 2016

Credit: Ruins campaign. Bani Waleed, September 2016

Credit: Ruins campaign. Bani Waleed, September 2016

The mural completed on 4 September depicts a child holding a hand grenade in place of a book, with the words “Children without schools” painted in English and Arabic.

When painting with fellow artists from the Ruins campaign – set up in May 2015 in collaboration with fellow artist Thi Yazen to paint on the walls of buildings damaged by the war – on 25 August, the group were arrested and interrogated by a local militia.

“They asked us to sign a letter with our fingerprints promising that we would not return again without permission,” Subay explains. “I actually did have permission from a local tribal leader but they wouldn’t listen.”

The artists were told if they returned they would be punished.

“My friends were very afraid and some of them said even with permission they would not return,” Subay said. “It was a strange situation for them.”

Subway himself isn’t put off and is already looking forward the next Ruins campaign, wherever that may be.

(2/2)whoever defaced the murals, wrote the word “steadfast” on both of them. #Yemen #Ruins_Campaign pic.twitter.com/3mhCfEulJT

— murad subay (@muradsubay) June 15, 2016

The last time he spoke with Index, Ruins had just completed a series of murals in front of the Central Bank of Yemen to represent the country’s economic collapse. Soon after the murals were finished, Houthi rebels defaced two out of the three works of art, writing “Samidoon” (صامدون), meaning “steadfast”, which is one of their slogans.

Assessing the situation in Yemen and the many different sides of the conflict, Subay said: “It is very difficult. Every night we hear airstrikes here and there, but we go on with our lives.”

“But any day when I can paint is a good one.”

Nominations are now open for 2017 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards and will remain open until 11 October. You can make yours here.

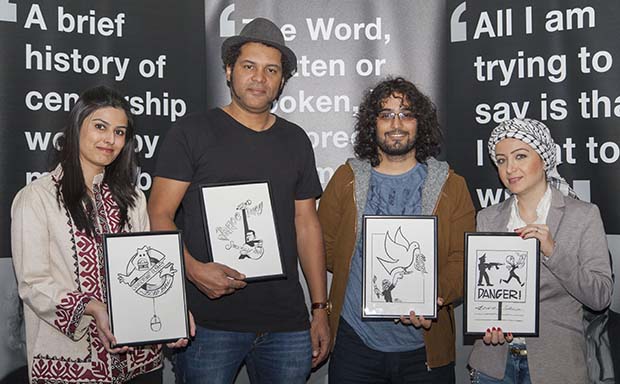

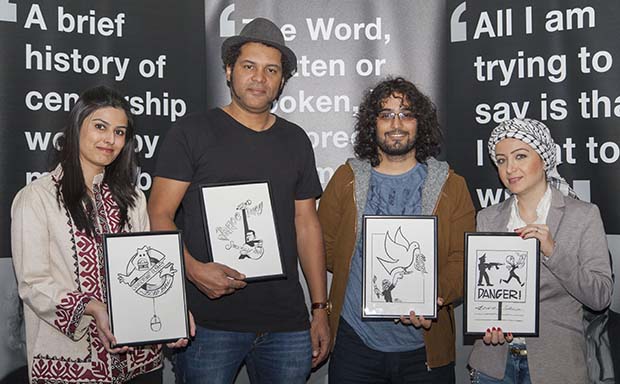

Winners of the 2016 Freedom of Expression Awards: from left, Farieha Aziz of Bolo Bhi (campaigning), Serge Bambara — aka “Smockey” (Music in Exile), Murad Subay (arts), Zaina Erhaim (journalism). GreatFire (digital activism), not pictured, is an anonymous collective. Photo: Sean Gallagher for Index on Censorship

Winners of the 2016 Freedom of Expression Awards: from left, Farieha Aziz of Bolo Bhi (campaigning), Serge Bambara — aka “Smockey” (Music in Exile), Murad Subay (arts), Zaina Erhaim (journalism). GreatFire (digital activism), not pictured, is an anonymous collective. Photo: Sean Gallagher for Index on Censorship

In the short three months since the Index on Censorship Awards, the 2016 fellows have been busy doing important work in their respective fields to further their cause and for stronger freedom of expression around the world.

GreatFire / Digital activism

GreatFire, the anonymous group of individuals who work towards circumventing China’s Great Firewall, has just launched a groundbreaking new site to test virtual private networks within the country.

“Stable circumvention is a difficult thing to find in China so this new site a way for people to see what’s working and what’s not working,” said co-founder Charlie Smith.

But why are VPNs needed in China in the first place? “The list is very long: the firewall harms innovation while scholars in China have criticised the government for their internet controls, saying it’s harming their scholarly work, which is absolutely true,” said Smith. “Foreign companies are also complaining that internet censorship is hurting their day-to-day business, which means less investment in China, which means less jobs for Chinese people.”

Even recent Chinese history is skewed by the firewall. The anniversary of Tiananmen Square protests of 1989 last month went mostly unnoticed. “There was nothing to be seen about it on the internet in China,” Smith said. “This is a major event in Chinese history that’s basically been erased.”

Going forward, Smith is optimistic for growth within GreatFire, and has hopes the new VPN service will reach 100 million Chinese people. “However, we always feel that foreign businesses and governments could do more,” he said. “We don’t see this as a long game or diplomacy; we want change now and so I feel positive about what we are doing but we have less optimism when it comes to efforts outside of our organisation.”

Winning the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award for Digital Activism has certainly helped morale. “With the way we operate in anonymity, sometimes we feel a little lonely, so it’s nice to know that there are people out there paying attention,” Smith said.

Murad Subay / Arts

During his time in London for the Index awards, Yemeni artist Murad Subay painted a mural in Hoxton, which was the first time he had worked outside of his home country. “It was a great opportunity to tell people what’s going on in Yemen, because the world isn’t paying attention,” he explained to Index.

Since going home, Subay has continued to work with Ruins, his campaign with other artists to paint the walls of Yemen. “We launched in 2011, and have continued to paint ever since.”

The Saw mural, Ruins campaign https://t.co/z7XrE2yTP7 pic.twitter.com/ZMiVjhxZO8

— murad subay (@muradsubay) June 10, 2016

Last month, artists from Ruins, including Subay, painted a number of murals in front of the Central Bank of Yemen to represent the country’s economic collapse.

Thi Yazen Alalawi mural, Ruins campaign https://t.co/c2wkosUIxy pic.twitter.com/UqmuSzczAl

— murad subay (@muradsubay) June 10, 2016

In his acceptance speech at the Index Awards, Subay dedicated his award to the “unknown” people of Yemen, “who struggle to survive”. There has been little change in the situation since in the subsequent months as Yemenis continue to suffer war, oppression, destruction, thirst and — with increasing food prices — hunger.

“The war will continue for a long time and I believe it may even be a decade for the turmoil in Yemen to subside,” Subay says. “Yemen has always been poor, but the situation has gotten significantly worse in the last few years.”

Subay considers himself to be one of the lucky ones as he has access to water and electricity. “But there are many millions of people without these things and they need humanitarian assistance,” he says. “They are sick of what is going on in Yemen, but I do have hope — you have to have hope here.”

The Index award has also helped Subay maintain this hope. As has the inclusion of his work in university courses around the world, from John Hopkins University in Baltimore, USA, and King Juan Carlos University in Madrid, Spain.

Subay’s wife has this month travelled to America to study at Stanford University. He hopes to join her and study fine art. “Since 2001 I have not had any education, and this is not enough,” he explains. “I have ideas in my head that I can’t put into practice because i don’t have the knowledge but a course would help with this.”

Zaina Erhaim / Journalism

Syrian journalist and documentary filmmaker Zaina Erhaim has been based in Turkey since leaving London after the Index Awards in April as travelling back to Syria isn’t currently possible. “We don’t have permission to cross back and forth from the Turkish authorities,” she told Index. “The border is completely closed.”

Erhaim is with her daughter in Turkey, while her husband Mahmoud remains in Aleppo.

“The situation in Aleppo is very bad,” she said. “A recent Channel 4 report by a friend of mine shows that the bombing has intensified, and the number of killings is in the tens per day, which hasn’t been the case for some weeks; it’s terrible.”

The main hospital in Aleppo was bombed twice in June. “Sadly this is becoming such a common thing that we don’t talk about it anymore,” Erhaim added.

She has largely given up on following coverage of the war in Syria through US or UK-based media outlets. “It is such a wasted effort and it’s so disappointing,” she explained. “I follow a couple of journalists based in the region who are actually trying to report human-side stories, but since I was in London for the awards, I haven’t followed the mainstream western media.”

Erhaim has put her own documentary making on hold for now while she launches a new project with the Institute for War and Peace Reporting this month to teach activists filmmaking skills. “We are going to be helping five citizen journalists to do their own short films, which we will then help them publicise,” she said.

Documentary filmmaking is something she would like to return to in future, “but at the moment it is not feasible with the situation in Syria and the projects we are now working on”.

Bolo Bhi / Campaigning

The last time Index spoke to Farieha Aziz, director of Bolo Bhi, the Pakistani non-profit, all-female NGO fighting for internet access, digital security and privacy, the country’s lower legislative chamber had just passed the cyber crimes bill.

The danger of the bill is that it would permit the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority to manage, remove or block content on the internet. “It’s part of a regressive trend we are seeing the world over: there is shrinking space for openness, a lot of privacy intrusion and limits to free speech,” Aziz told Index.

Thankfully, when the bill went to the Pakistani senate — which is the upper house — it was rejected as it stood. “Before this, we had approached senators to again get an affirmation as they’d given earlier saying that they were not going to pass it in its current form,” Aziz added.

Bolo Bhi’s advice to Pakistani politicians largely pointed back to analysis the group had published online, which went through various sections of the bill and highlighting what was problematic and what needed to be done.

This further encouraged those senators who were against the bill to get the word out to their parties to attend the session to ensure it didn’t pass. “It’s a good thing to see they’ve felt a sense of urgency, which we’ve desperately needed,” Aziz said.

“The strength of the campaign throughout has actually been that we’ve been able to band together, whether as civil society organisations, human rights organisations, industry organisations, but also those in the legislature,” Aziz added. “We’ve been together at different forums, we’ve been constantly engaging, sharing ideas and essentially that’s how we want policy making in general, not just on one bill, to take place.”

The campaign to defeat the bill goes on. A recent public petition (18 July) set up by Bolo Bhi to the senate’s Standing Committee on IT and Telecom requested the body to “hold more consultations until all sections of the bill have been thoroughly discussed and reviewed, and also hold a public hearing where technical and legal experts, as well as other concerned citizens, can present their point of view, so that the final version of the bill is one that is effective in curbing crime and also protects existing rights as guaranteed under the Constitution of Pakistan”.

A vote on an amended version of the bill is due to take place this week in the senate.

Smockey / Music in Exile Fellow

Burkinabe rapper and activist Smockey became the inaugural Music in Exile Fellow at the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards, and last month his campaigning group Le Balai Citoyen (The Citizen’s Broom) won an Amnesty International Ambassador of Conscience Award.

“This was was given to us for our efforts in the promotion of human rights and democracy in our country,” said Smockey. The award was also given to Y en a marre (Senegal) and Et Lucha (Democratic Republic of the Congo).

“We are trying to create a kind of synergy between all social-movements in Africa because we are living in the same continent and so anything that affects the others will affect us also,” Smockey added.

Le Balai Citoyen has recently been working on programmes for young people and women. “We will also meet the new mayor of the capital to understand all the problems of urbanism,” Smockey added.

While his activism has been getting international recognition, he remains focused on making music with upcoming concerts in Belgium, Switzerland and Germany, and he is currently writing the music for an upcoming album. A major setback has seen Smockey’s acclaimed Studio Abazon destroyed by a fire early in the morning of 19 July. According to press reports the studio is a complete loss. The cause is under investigation.

Despite this, Smockey is still planning to organise a new music festival in Burkina Faso. “We want to create a festival of free expression in arts,” Smockey said. “And we are confident that it will change a lot of things here.”

He is thankful for the exposure the Index Awards have given him over the last number of months. “It was a great honour to receive this award, especially because it came from an English country,” he said. “My people are proud of this award.”

Words by Alessio Perrone and Sean Gallagher

Photos: Sean Gallagher

“I invite people like this: I just say – you paint now.” That’s how it works with street artist Murad Subay.

His murals grew from the frustration he felt as his homeland, Yemen, descended into chaos and factionalism. Amid the destruction and anger, Subay picked up his brush. With friends, he went out into the streets and began painting in broad daylight. Days passed, then people from the community joined him. All of them driven by their desire for peace amid Yemen’s civil war.

Since 2011 he’s created campaigns to encourage Yemenis to express their outrage at what their country has become. He and his collaborators have coloured walls, named the disappeared and marked ruins.

He always works during the day. It’s always part performance, part collaboration. Thursday 14 April was no different. Only the location had changed.

For his first mural outside Yemen, Subay took his brushes and paint to the corner of Hackney Road and Cremer Street to send a pointed message about the international community’s lack of humanity, especially toward his homeland. Even dogs are better than some of the global institutions and structures.

In London, to receive the 2016 Freedom of Expression Arts Award for his work, which Subay stressed is for Yemen. His acceptance speech was dedicated to the “unknown people who struggle to survive”.

Invited by Jay, the community curator of Art Under the Hood, Subay set up his equipment — with the help of new friends — and began transforming a hoarding into his vision using stencils he had laboured over since arriving on Saturday.

“I’m doing a sun dance.”

“I’m not the type of artist who zones out and thinks this is precious. It’s an ordinary thing for me”

“How long will it take for it to dry?”

“In Sana’a, three minutes!” Then a few seconds later “Here, I don’t know”

“Do you want me to do anything”

“Yes of course. Come here”

“Welcome to the holy state of Hackney, my friend. This is not a borough, not a city, it’s a state.”

“I’ve worked on these stencils from time to time for four days. It’s hard to say how long it takes. Sometimes it takes three, four hours, other times five … Depends on what I do”

“First, try it on the cardboard to see how strong or light it is. Then press in the shape, light, not strong. Keep it at an angle close to the margins, so you can make sure you don’t spray outside the shape. Then perpendicular in the middle. Keep it light, light!”

“Can I have a go?” a young woman asks.

“Yes of course!”

She stops for a moment, hesitant. Then she ends up staying until the very end. And in the end, Subay gives her, Éléa, the stencils when he finishes the mural.

“Do you paint?”

“A bit”

“Not a bit, you have to paint a lot! Painting is beautiful.”

“They have artists in Yemen? First time I hear that!”

“You know how to spray right? Come and learn a bit!”

“When I started out, I was alone, and I did it all in one week. I am slow. In the beginning, I never thought people could join. But then they did. They say: ‘Oh look, the artist!’ And they join”

“These stencils, I made in Yemen. I staged a photo, printed it, then cut it out. That chained man is one of my relatives. He’s a very nice person. He jokes a lot and loves painting. I really like him. We work together a lot, on street art of course but also many different things.”

“It’s all about how the man is suffering. He’s not just Yemen or anybody in particular. It could be any man. The dog is trying to help, and is showing more kindness then the other man. The dog shows that it’s possible to help out, but the other man doesn’t want to do anything.”