9 May 2019 | Awards, Fellowship, Fellowship 2018, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Cuban artists Luis Manuel Otero Alcantara and Yanelys Nuñez Leyva, members of the Index-award winning Museum of Dissidence

Yanelys Nuñez Leyva and Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara, members of the 2018 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award-winning Cuban artist collective the Museum of Dissidence, have been putting themselves on the line in the fight for free expression in Cuba, from being harassed by the authorities to their numerous arrests for protesting Decree 349, a vague law intended to severely limit artistic freedom in the country.

Cubans voted overwhelmingly for a new constitution that upholds the one-party state while claiming to bring about some economic and social reform, but the Museum of Dissidence took a more critical stance to the referendum. Index caught up with Nuñez Leyva and Otero Alcántara to talk about the current situation in Cuba and what they’ve been up to recently.

Index on Censorship: Why did the Museum of Dissidence and its members come out so strongly against the new Cuban constitution?

Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara: The constitution imposed by the regime is an aberration that goes against the freedom of the Cuban and does not represent us as Cubans, intellectuals or humans. The Magna Carta should not be written to control and cut my freedom, it must represent a balance of citizen welfare especially for the immediate future.

Index: Decree 349 will see all artists prohibited from operating in public places without prior approval from the Ministry of Culture. How does this impact the work you do?

Otero Alcántara: The campaign against the 349 was a great victory, the regime had to admit that it was wrong. The country’s leaders had to face and make political moves to placate countless artists, intellectuals and ordinary people concerned about Cuban culture and who joined in the demands to the regime.

Given this, the 349 helped to make visible all the repression and censorship that the government has been carrying out against culture and art for 60 years. As a legacy, we left the movement of San Isidro, a group of artists and intellectuals that has the mission to overcome all the inhumane repression of the regime, to be vigilant and proactive over freedom of Cuban art and culture. The most important project of the post-campaign movement 349 will be the Observatory of Cultural Rights in Cuba.

Index: What sort of training did Yanelys Nuñez Leyva receive while in Prague as part of the Freedom of Expression Awards Fellowship and how will it be useful in Museum of Dissidence?

Yanelys Nuñez Leyva: The training covered tools I can use for work, such as video editing. It also offered insight into new topics such as feminism, a social movement that is not yet as strong in Cuba but should be.

Index: What did Museum of Dissidence do while in Mexico at the Oslo Freedom Forum and how will this help further your cause?

Otero Alcántara: The MDC joined several independent institutions in Cuba such as the Matraca Project, or the Endless Poetry Festival, so that each one, from his or her experience, would demand freedom of expression for all Cubans in a forum.

In all the presentations, we emphasised the unjust detention of two Cuban musicians, Maikel Castillo and Pupito, who are imprisoned for opposing Decree 349.

Index: How did attending Libertycon in Washington DC reinforce or re-inspire your fight for artistic freedom in Cuba?

Luis Manuel: All these events we have been a part of, such as Forum 2000, or the Index award, or the residency in Metal, have helped to create a platform where contemporary art ceases to be an ornament in a house but an exercise of pressure and a true link of change within Cuba.

Index: Although nearly 87% of voters in the referendum voted yes to the new constitution, there was an unprecedented display of ballot-box dissent, with more than 700,000 people voting no. What do you think this is a result of and do you think this signifies changing times for the Cuban population and government?

Otero Alcántara: In a totalitarian regime like the one in Cuba, where it controls all the information, international observers and legal transparency systems are not allowed, those percentages are strategies of the regime to simulate a less critical state than the one that exists. Those numbers are a joke but the interesting thing is to see how the political opposition handles that ‘no.’ Making ordinary people see that they are not alone, that other thousands of people feel and voted just like them, is something that contributes to encouraging dissent.

Index: What makes you remain so steadfast in your fight for artistic expression in Cuba when the oppression of artists continues, including the recent arrest of members of the Museum of Dissidence?

Otero Alcántara: Love binds me, wherever I want to escape, from the shelter of the pillow in the darkness of my room; going through a luxurious hotel in Miami or in a bucolic countryside in the UK, the suffering of Cuba and the human is shaking my head and the only way I can free myself from that ghost is to fight and know that I am doing something.

Last December when the government promised to implement the 349, I felt that my spirit was imprisoned in the body of a regime, so I took responsibility for the life of my body through a hunger strike to the regime. It would be they who would decide if I was still breathing my body or not but my spirit would be free.

Luckily, we got a reaction from the government. They appeared on Cuban television, and that was because of the union that was achieved among all the artists.

Index: What are the main goals that you’ll be working toward throughout 2019?

Otero Alcántara: 2019 is the year of the official state-sponsored Havana biennial and a year of preparation for the #00 Biennial of 2020, which are two interesting scenarios for the future of Cuban culture right now. The other thing is to continue working for overall freedom in Cuba.

Index: How has the Museum of Dissidence benefitted from its time on the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards Fellowship?

Otero Alcántaral: Being Index Fellows was one of the best things that has happened to the museum in its history as a work of art and an institution. It was a prize that gave visibility to the Musem of Dissidence and gave us thousands of contacts. It gave us protection against the repression of the regime and its discredit toward political art in Cuba. But above all we met people like Perla Hinojosa and the rest of the Index team, also Mohamed Sameh from ECRF, Julie Tribault, the promoters of the Metal artistic residency and another large number of projects and platforms that, with their example, have encouraged us to continue the struggle, especially in the moments of greatest loneliness.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1583501159250-00b68107-bcde-1″ taxonomies=”7874″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

18 Jan 2019 | Awards Update, Fellowship, Fellowship 2018, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]The Index Awards Fellowship has become an important element of Index on Censorship’s work – allowing us to help those on the frontlines of defending free speech around the world. Each fellow receives a structured programme of assistance including capacity building, mentoring and networking. Over the course of a year, we also help them accomplish a key goal that will significantly enhance the impact or sustainability of their work.

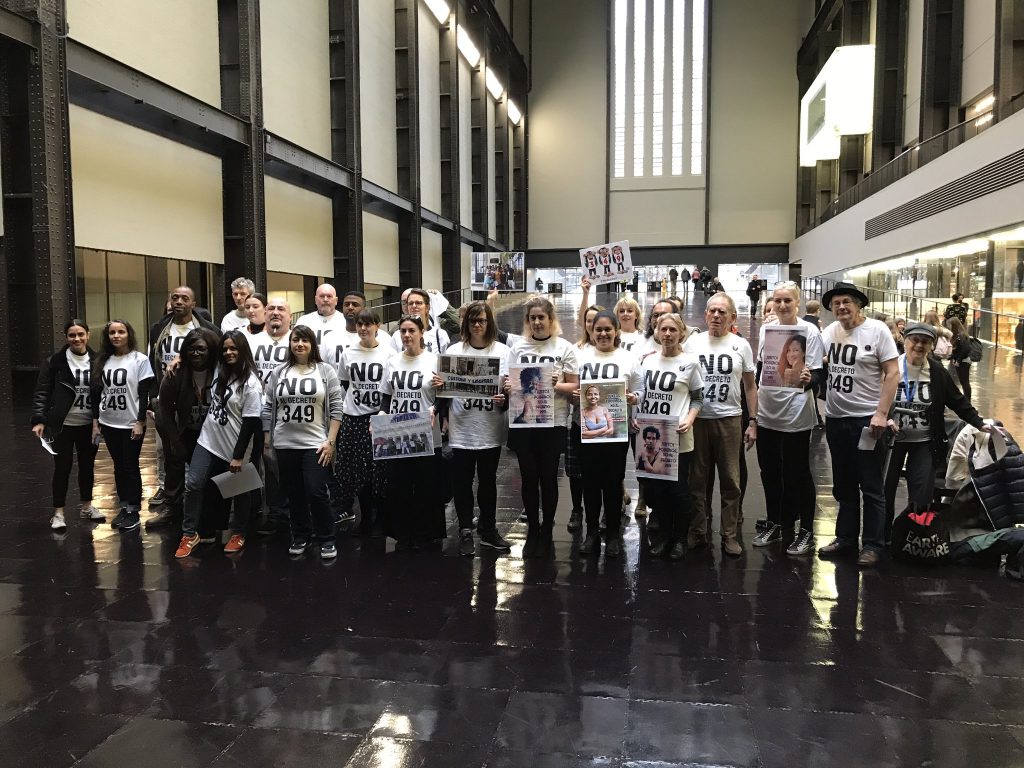

The 2018 Fellows are continuing to thrive:[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”103306″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Arts fellow the Museum of Dissidence, led by artist Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara and art curator Yanelys Nuñez Leyva, have put themselves on the line in the fight against Decree 349, a vague law intended to severely limit artistic freedom in Cuba. In November, the two were arrested for peacefully protesting the law. Index campaigned for their release at a solidarity protest at Tate Britain.

Having missed our Freedom of Expression Awards ceremony in April 2018, we were thrilled to present Nuñez Leyva and Otero Alcántara with their award in October at Metal Culture Southend, an arts centre where they were taking part in a two-week residency.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”99812″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]Campaigning fellows the Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms continue to highlight human rights abuses and provide support for those facing repression. The group has expanded its reach by opening two new offices around the country and has benefited from technology training provided by Index. Amal Fathy, wife of ECRF executive director Mohamed Lotfy, was released from prison in late December after eight months in detention for her online criticism of sexual harassment in Egypt, but a two-year prison sentence was upheld against the activist, raising fears she could again end up behind bars. Index continues to campaign for Amal at international level.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”99888″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Digital Activism fellow Habari RDC, a collective of more than 100 young Congolese bloggers and web activists, have been busily covering December’s tense election in the Democratic Republic of Congo and its fallout. Guy Muyembe, president of Habari RDC, said before the elections: “The only thing that is certain about the election is the uncertainty that comes with it.” The continuing tensions threaten to destabilise the country, insecurity and violence. Index has arranged training for Habari RDC with Protection International which will take place early this year.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”99885″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Journalism fellow Wendy Funes continues to cover corruption and human rights violations in Honduras, a country where violence has become “normalised”. With the help of Index, Wendy is in the process of securing an office for her newspaper which will create a safe space for her team to do their work. She also plans to open the space to other journalists and offer training to students. Wendy has been selected as a judge for the UNESCO/Guillermo Cano World Press Freedom Prize and has been able to attain funding which will cover some of her investigations for 2019.[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”99904″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1547745843103-843df51b-4519-5″ taxonomies=”8935″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

11 Jan 2019 | Awards, Awards Update, Fellowship, Fellowship 2018, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Yanelys Nuñez Leyva and Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara. The Museum of Dissidence

2018 Freedom of Expression Awards at Metal, Chalkwell Park, Essex.

Artistic freedom is under attack in Cuba, but artists are fighting back. Yanelys Nuñez Leyva and Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara, members of the 2018 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award-winning Cuban artist collective the Museum of Dissidence, along with many others, are putting themselves on the line in the fight against Decree 349, a vague law intended to severely limit artistic freedom in the country. Decree 349 will see all artists — including collectives, musicians and performers — prohibited from operating in public places without prior approval from the Ministry of Culture.

“349 is the image of censorship and repression of Cuban art and culture, and is also an example of the exercise of state control over its citizens,” Otero Alcántara tells Index. “Artists, in a spectacular way, must work in a state of double resistance, as artists and as activists, because the system has control over all opportunities for artistic growth.”

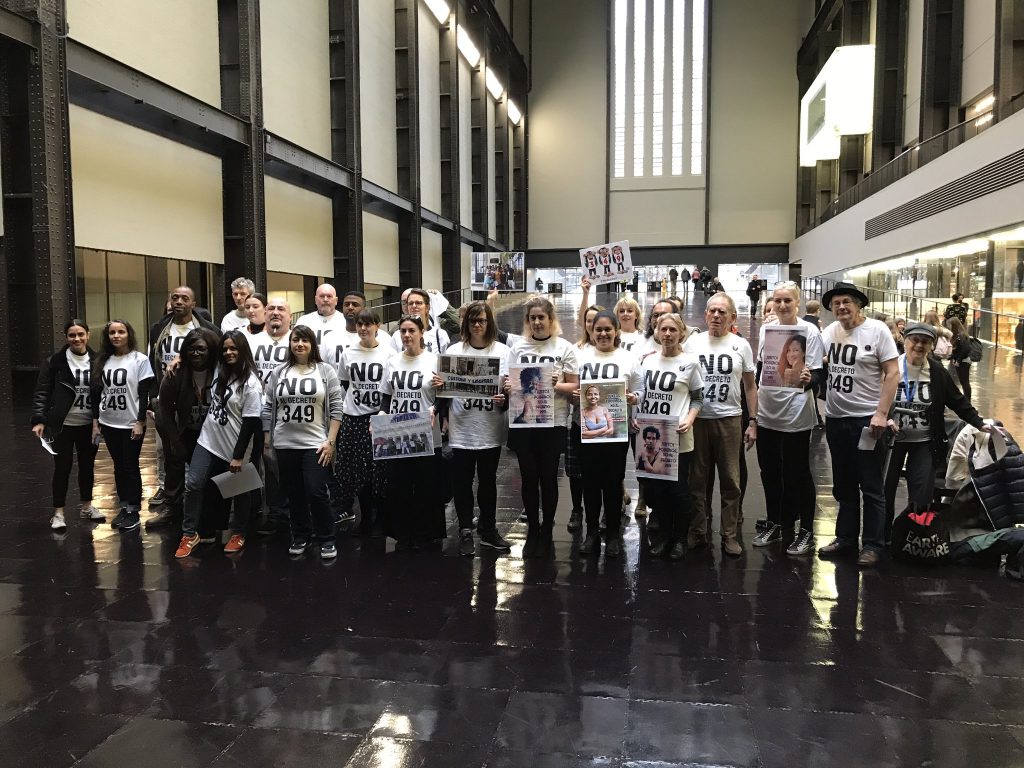

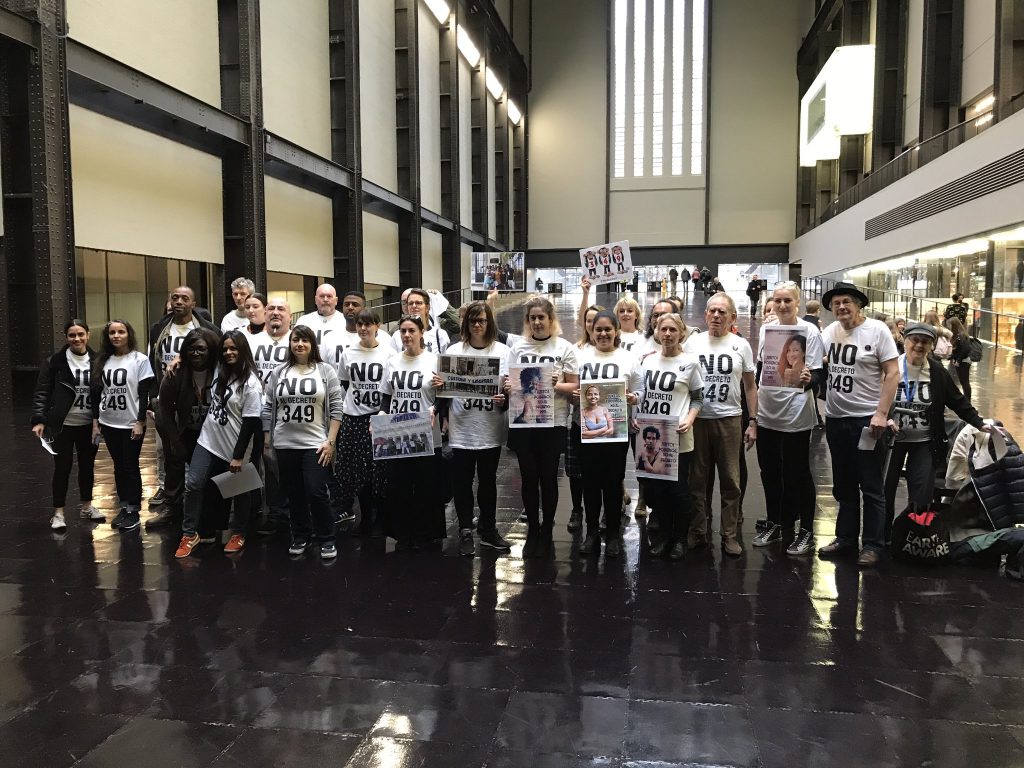

For their role in peacefully protesting Decree 349, Otero Alcantara and Nuñez Leyva were among 13 artists arrested, including Cuban performance artist Tania Bruguera, in Havana on 3 December 2018. Index joined others at the Tate Modern in London on 5 December in a show of solidarity with those jailed.

Protest in support of jailed Cuban artists at the Tate Modern gallery, London, October 2018.

On Human Rights Day on 10 December 2017, US Assistant Secretary of State Kimberly Breier tweeted: “[O]ur minds turn to the people of #Cuba, who have endured decades of repression and abuse at the regime’s hands, most recently via the creativity-crushing #Decree349.”

“The international help is positive because it makes visible the abuses of the Cuban regime against the people, but I think we must sacrifice ourselves in body and spirit — in a peaceful way — if we want to achieve our freedom,” Nuñez Leyva tells Index on Censorship. “We are very grateful for any help and pronouncements against 349. The redaction of the decree and the silence of the authorities is demonstrating that in Cuba there is a dictatorial regime in which no type of political, economic or social opening is taking place.”

In the days following all arrested artists were released, although they remained under police surveillance. Cuba’s vice minister of culture Fernando Rojas at the time told the Associated Press that changes would be made to Decree 349 but failed to open a dialogue with the artists involved in the campaign against the decree. A version of the law came into force on 7 December.

“We are determined to continue demanding the full repeal of 349,” Nuñez Leyva says. “We do not want to continue living in this perennial state of vulnerability.”

The persecution of the Museum of Dissidence isn’t limited to arrests. On 9 November Otero Alcántara took to Facebook to call out a campaign to discredit him. State security had been sending texts and holding meetings with his neighbours in what the artist said was a “desperate attempt” to “sabotage our activities”.

“The rhetoric that the government uses is well known to all — that we are mercenaries — and although most people no longer believe it, some of them decide to exclude you because you are a ‘marked’ person like you have a contagious disease,” Otero Alcántara tells Index. “You are a socially excluded and politically persecuted.”

“We try all the time not to give it too much importance, we try to smile because we really do not want to feel any bad energy,” he adds. “Our principle is love, dialogue, peaceful struggle. If they wish to defame us, it is on their conscience, not ours.”

Cuban artists Luis Manuel Otero Alcantara and Yanelys Nuñez Leyva, members of the Index-award winning Museum of Dissidence

Nuñez Leyva describes the efforts to dissuade Cuban artists from protesting 349 — including the seizure of anti-349 t-shirts emblazoned with three wise monkeys when re-entering Cuba after attending the Creative Time Summit in Miami — as “a mechanism to prevent the spread of the truth and above all, to make us tired and to resort to leaving the country”. But the Museum of Dissidence will not be deterred. “To achieve that, they will have to be more vicious.”

“The government spends innumerable resources to repress any type of expression that makes it uncomfortable,” Otero Alcántara says. “It seeks to discredit activists and artists all the time by isolating them from society, from their friends, from their family.”

After a seven-month campaign to attain visas to enter the UK — which saw the Museum of Dissidence denied visas on three occasions, causing them to them miss the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards ceremony in April 2018 — Nuñez Leyva and Otero Alcántara were finally able to receive their award at Metal Culture, an arts centre in Chalkwell Hall, Southend-on-Sea, on 18 October 2018. The artists were in residence at Metal for two weeks in October as part of their partnership with Index on Censorship.

“Southend-on-Sea generously gave us all its warmth. Staff at Metal, the uncharacteristically warm climate, the brick architecture of the place, the low tide river, the local legends told by a science fiction writer, the banks that paid homage to the deceased, the interest of the local media in the Cuban cause were encouraging for us,” Nuñez Leyva says. “To realise that a calm, inclusive city is possible opens us up and make us less naive when going back to face the Cuban reality.”

Luis Manuel Otero Alcantara as Miss Bienal

During his time in the UK, Otero Alcántara performed in Trafalgar Square on 26 October as Miss Bienal, a character he created in 2016 to symbolise the mulatto woman typified in clichés by tourist and for artistic consumption.

“Entering the National Gallery in a rumba dress without censorship made us realise the context of freedom and acceptance of difference that is breathed in London,” he says. “London is a giant city with so much art, diversity and history, it makes the body detoxify a bit from the bad energy you get living in a system like the Cuban one.”

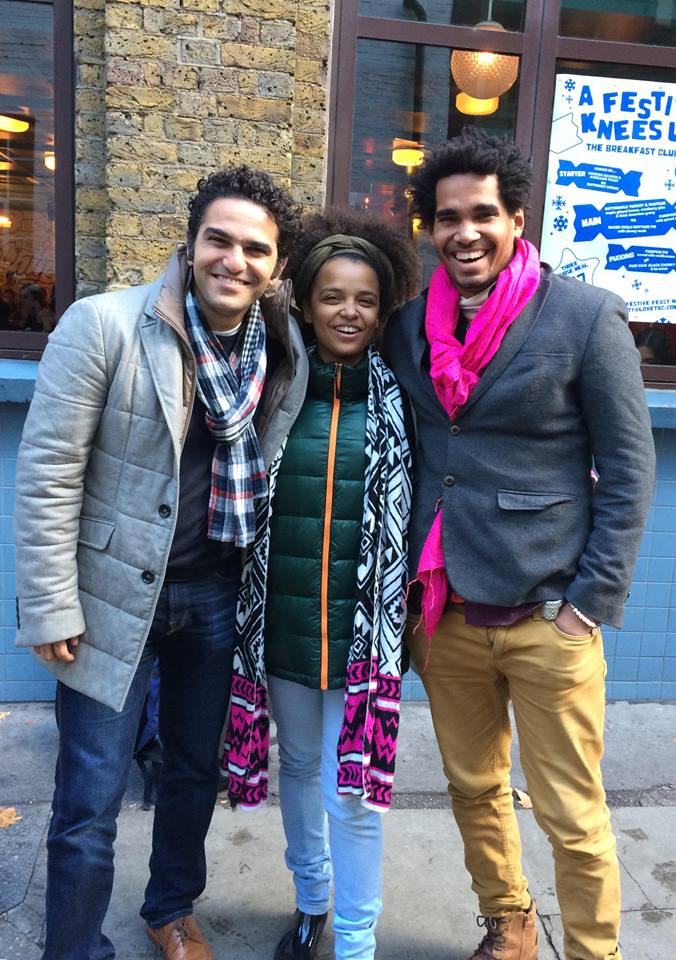

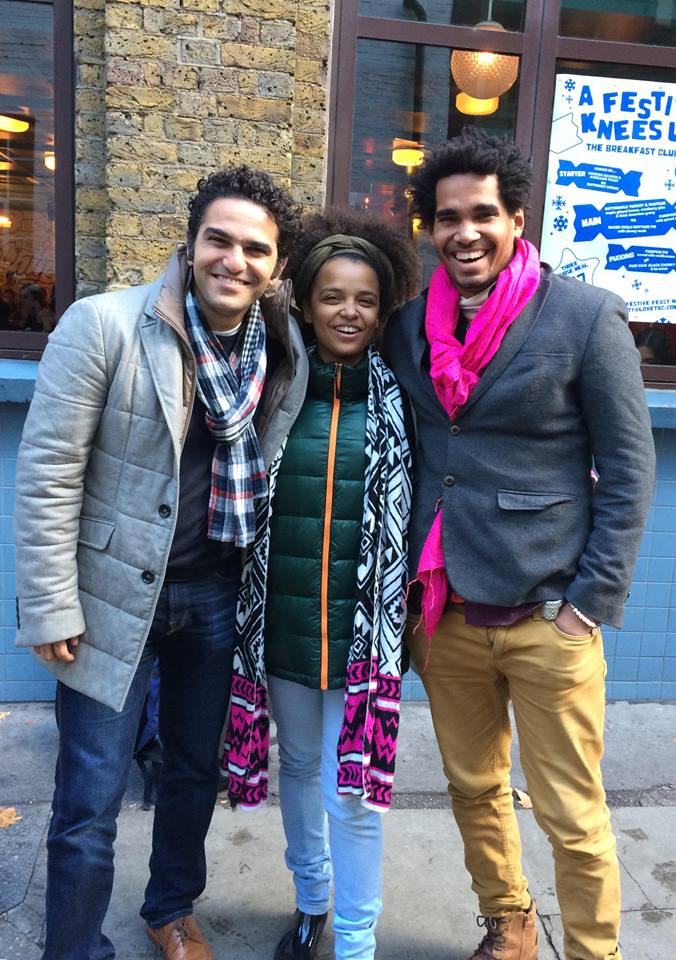

Mohamed Sameh with Yanelys Nuñez Leyva and Luis Manuel Otero Alcantara in London

While in London, the pair met with Mohamed Sameh, co-founder and international relations advisor at the Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms, winner of the 2018 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award for Campaigning. ECRF is one of the few remaining human rights organisations in Egypt, a country that often uses its struggle against terrorism as a justification for its crackdown on human rights.

“We shared with Mohamed the desire for prosperity in our respective countries, but also the smile that we shared, which we hold on to all the time,” Nuñez Leyva says. “The contagious smile of Mohamed is similar to that of, not only of the Museum of Dissidence in Cuba, but also Amaury Pacheco, Iris Ruiz, Coco Fusco, Student without Seed, Michel Matos, Aminta D’Cardenas, La Alianza, Yasser Castellanos, Veronica Vega, Javier Moreno, Tania Bruguera, and other artists who at this moment are fully engaged in the improvement of Cuba.”

“Although our contexts are different, we feel a total empathy with the struggles of Mohamed, because in our work we put ourselves at risk all the time for our rights and total freedom of expression, principles that for Mohamed are also non-negotiable.” [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1547483905239-0a56285c-5eb0-10″ taxonomies=”23707″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

5 Dec 2018 | Artistic Freedom, Awards, Cuba, Fellowship, Fellowship 2019, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Update: All arrested artists have now been released, although they remain under police surveillance. Cuba’s vice minister of culture Fernando Rojas has declared to the Associated Press that changes will be made to Decree 349 but has not opened dialogue with the artists involved in the campaign against the decree.

Index on Censorship joined others at the Tate Modern on 5 December in a show of solidarity with those artists arrested in Cuba for peacefully protesting Decree 349, a law that will severely limit artistic freedom in the country. Decree 349 will see all artists — including collectives, musicians and performers — prohibited from operating in public places without prior approval from the Ministry of Culture.

In all, 13 artists were arrested over 48 hours. Luis Manuel Otero Alcantara and Yanelys Nuñez Leyva, members of the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award-winning Museum of Dissidence, were arrested in Havana on 3 December. They are being held at Vivac prison on the outskirts of Havana. The Cuban performance artist Tania Bruguera, who was in residency at the Tate Modern in October 2018, was arrested separately, released and re-arrested. Of all those arrested, only Otero Alcantara, Nuñez Leyva and Bruguera remain in custody.

Index on Censorship’s Perla Hinojosa speaking at the Tate Modern.

Speaking at the Tate Modern, Index on Censorship’s fellowships and advocacy officer Perla Hinojosa, who has had the pleasure of working with Otero Alcantara and Nuñez Leyva, said: “We call on the Cuban government to let them know that we are watching them, we’re holding them accountable, and they must release artists who are in prison at this time and that they must drop Decree 349. Freedom of expression should not be criminalised. Art should not be criminalised. In the words of Luis Manuel, who emailed me on Sunday just before he went to prison: ‘349 is the image of censorship and repression of Cuban art and culture, and an example of the exercise of state control over its citizens’.”

Other speakers included Achim Borchardt-Hume, director of exhibitions at Tate, Jota Castro, a Dublin-based Franco-Peruvian artist, Sofia Karim, a Lonon-based architect and niece of the jailed Bangladeshi photojournalist Shahidul Alam, Alistair Hudson, director of Manchester Art Gallery and The Whitworth, and Colette Bailey, Artistic director and chief executive of Metal, the Southend-on-Sea-based arts charity.

Some read from a joint statement: “We are here in London, able to speak freely without fear. We must not take that for granted.”

It continued: “Following the recent detention of Bangladeshi photographer Shahidul Alam along with the recent murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi, there us a global acceleration of censorship and repression of artists, journalists and academics. During these intrinsically linked turbulent times, we must join together to defend our right to debate, communicate and support one another.”

Castro read in Spanish from an open declaration for all artists campaigning against the Decree 349. It stated: “Art as a utilitarian artefact not only contravenes the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Cuba is an active member of the United Nations Organisation), but also the basic principles of the United Nations for Education, Science and Culture (UNESCO).”

It continued: “Freedom of creation, a basic human expression, is becoming a “problematic” issue for many governments in the world. A degradation of fundamental rights is evident not only in the unfair detention of internationally recognised creatives, but mainly in attacking the fundamental rights of every single creator. Their strategy, based on the construction of a legal framework, constrains basic fundamental human rights that are inalienable such as freedom of speech. This problem occurs today on a global scale and should concern us all.”

Cuban artists Luis Manuel Otero Alcantara and Yanelys Nuñez Leyva, members of the Index-award winning Museum of Dissidence

Mohamed Sameh, from the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award-winning Egypt Commission on Rights and Freedoms, offered these words of solidarity: “We are shocked to know of Yanelys and Luis Manuels’s detention. Is this the best Cuba can do to these wonderful artists? What happened to Cuba that once stood together with Nelson Mandela? We call on and ask the Cuban authorities to release Yanelys and Luis Manuel immediately. The Cuban authorities shall be held responsible of any harm that may happen to them during this shameful detention.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1544112913087-f4e25fac-3439-10″ taxonomies=”23772″][/vc_column][/vc_row]