26 Sep 2018 | Awards, Fellowship, Fellowship 2018, News, Press Releases

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/-UpVto-2Sf0″][vc_column_text]The UK has refused visas for a second time to two award-winning Cuban artists who had been invited to take up a two-week artistic residency.

Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara and Yanelys Nuñez Leyva, winners of this year’s Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards for Arts, had also been due to collect their award. They had been scheduled to receive their honour in April at the Index award ceremony in London but were denied visas to attend.

“We had hoped that – having been recognised with this award, and given the fact Luis Manuel and Yanelys have been granted visas to Argentina, Chile, the Czech Republic, and the United States this year – the UK government would give them the opportunity to visit the UK,” said Index on Censorship Fellowships and Advocacy Officer Perla Hinojosa.

Alcántara and Nunez are founders of The Museum of Dissidence, a public art project and website celebrating dissent in Cuba. Set up in 2016, the museum organises radical public art projects and installations, concentrated in the poorer districts of Havana.

Last month, Cuban authorities arrested Nuñez and Alcantara for their role in organising a concert against Decree 349, a vague law that will give the government more control over the display and exchange of art. The law, due to come into force on 1 December 2018, gives the Ministry of Culture increased power to censor, issue fines and confiscate materials for work of which they do not approve. The pair were beaten during their detention.

It was the second arrest in three weeks for Alcantara in relation to Decree 349.

“The UK makes much of its support for freedom of expression,” said Index on Censorship chief executive Jodie Ginsberg. “But while it talks the talk, it fails to walk the walk. Denying visas to artists who have faced oppression in their own countries for speaking out simply emboldens the oppressor.”

In August, directors of some of Britain’s biggest festivals signed a letter calling for the government to make its “overly complex” visa application process more transparent, after a surge in refusals and complications for authors, artists and musicians invited to perform in the UK.

Signatories of the letter included Nick Barley, the director of Edinburgh international book festival, and Chris Smith, the director of Womad after both went public with their festivals’ attempts to get visas for authors and musicians.

Yana Peel, CEO of the Serpentine Galleries and a judge of this year’s Freedom of Expression Awards said: “This is extremely disappointing news. Artists from overseas are being unfairly treated by the current visa system and it is beginning to have a significant impact on our programmes and events. In today’s climate, it is especially important that artists coming to Britain know that they are welcome.”

Nunez and Alcantara – who had been due to take up a two-week residency with Metal in Southend – were refused their visas on the grounds of insufficient evidence they would be able to support themselves financially during their stay.

“That’s nonsense,” said Hinojosa. “We provided ample evidence of the support they would receive and that Index would stand as guarantor. We have run our awards for nearly 20 years and never had any of our winners overstay or breach their visa terms.”

Colette Bailey, CEO and Artistic Director of Metal, said: “We are incredibly disappointed not to be welcoming Nunez and Alcantara to the UK as part of our International Artists in Residence programme. Our artists in residence programme is a platform for the exchange of ideas, culture and knowledge between artists from around the world and our local communities and young people. It is activity like this that contributes to the creativity of Britain, across sectors, and our enviable reputation as a creative powerhouse. This refusal is part of a worrying trend that cannot go unchallenged.”

In 2016, Index complained to UK authorities after UK border officials confiscated the passport of Syrian journalist, Zaina Erhaim who had been invited in her capacity as that year’s winner of the Freedom of Expression Award for journalism to speak at an event alongside veteran journalist Kate Adie.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1537976994705-c0f32970-0b8a-0″ taxonomies=”23772″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

21 Aug 2018 | Awards, Awards Update, Fellowship, Fellowship 2018, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Museum of Dissidence’s Luis Manuel Otero Alcantara arrested on 21 July 2017

From the outside, we could be forgiven for thinking the Cuban art scene is thriving. Demand for Cuban art is high among international collectors while Cuban artists — at least those the state approves of — enjoy a privileged position in society. However, those without state accreditation don’t tend to experience such visibility and recognition. For them, creating without arousing the suspicion of the authorities is a struggle.

The Cuban art collective the Museum of Dissidence, which won the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards Fellowship for Arts in April 2018, is supporting a new generation of artists in order to challenge this status quo. For their efforts they have been quite publicly punished by the state, but their list of successes is growing every step of the way.

Cuban authorities arrested artists Yanelyz Nuñez and Luis Manuel Otero Alcantara, members of the Museum of Dissidence, from Otero Alcantara’s home early on the morning of Saturday 11 August for their role in organising a concert against Decree 349, a vague law that will give the government more control over the display and exchange of art. The law, due to come into force on 1 December 2018, gives the Ministry of Culture increased power to censor, issue fines and confiscate materials for work they don’t approve of. During the hours the pair spent in prison, when they were beaten and interrogated, their families and friends did not know where they were, and the authorities denied any knowledge of what had happened to them.

This was the second time in three weeks that Otero Alcantara had been arrested in relation to Decree 349. On 21 July, Nuñez stood alone on the steps of the National Capitol Building in Havana, covered in human excrement. This was supposed to be part of a protest against the new law but her counterparts, including Otero Alcantara, had been arrested.

The arrests have had the unintended consequence of raising awareness of the campaign against the law. Upon release, Otero Alcantara has always been defiant, writing on 11 August: “Tomorrow we will continue the fight against the Degree 349.”

“We stand in solidarity with the brave artists and activists who, despite clear repression, stand up for fundamental human rights of Cubans,” Perla Hinojosa, fellowships and advocacy officer at Index on Censorship, said. “Arrests, violence and intimidation should never be responses to self-expression, and we call for such acts of censorship to stop. Any law that makes art a crime is unjust and we urge our supporters to sign the petition against Decree 349.”

“We belong to a generation that wants urgent improvements,” Otero Alcantara tells Index on Censorship. “A generation that, although it has no political culture, knows what it wants. We want to rebuild Cuba, but change will not be easy.”

Cuban artist Yasser Castellanos at #00Bienal de la Habana

As part of their mission to change the country, Nuñez and Otero Alcantara helped organise the ten-day #00Bienal de la Habana, which included over 170 artists, writers, musicians and theorists across nine different exhibitions in artists’ homes and studios around the country’s capital. It was Cuba’s first non-state sanctioned art biennial. Nuñez says its independence led to it being “persecuted by the Cuban state,” but added that its success nonetheless “exceeded our expectations”.

“From the beginning, we wanted to create an event that had a real and forceful impact inside the island, but at times we questioned the power of the art in transforming things,” she says. “But we were satisfied with the results — they helped us to recover our faith in Cuba, in art and Cubans.”

“The impact was so strong that we have heard that in cultural institution meetings, creators and journalists who are typically critical of what we do, have spoken favourably of the biennial,” says Otero Alcantara.

The influence has not stopped at Cuba’s shores, with Cuba’s diaspora looking on. “Many of them have shown us admiration for what we do in Cuba,” Otero Alcantara says. “We even plan to collaborate with many of them, while there are others we have already worked with.”

“The connection between Cubans of the diaspora and those who live inside is getting greater each day, and has increased with what internet the regime allows and a common interest in the country’s rich cultural history,” Nuñez says.

Life for those artists who are critical of the regime can be volatile, and even dangerous. When asked if their treatment ever makes them feel like joining the Cuban diaspora overseas, the pair stands firm.

“Cuba is my birthplace and my homeland. It’s like my house, where I should be able to walk naked from the living room to the kitchen without problems,” Otero Alcantara says. “As long as the forces don’t get me, I will fight for change and to improve my Cubanness.”

For Nuñez, meeting Cuban artists like Amaury Pacheco and Iris Ruiz has encouraged her to stay. “We are such a rich country and we have so much to offer that in some way that helps me stay,” she says. “The projects that I have been involved in recent years have excited me a lot.”

Perla Hinojosa, Fellowship and Advocacy Officer at Index on Censorship, holds the 2018 Freedom of Expression Arts Award for Cuban arts collective Museum of Dissidence, who could not attend the Freedom of Expression Awards. (Photo: Index on Censorship)

Winning the Index on Censorship award, Nuñez explains, has helped them in their work, increasing visibility and opening them up to collaborations with the likes of Artists at Risk Connection, a New York-based organisation that provides residencies for artists in extremely difficult situations. “Given the levels of disconnection in Cuba, these relationships with international organisations and activist movements in favour of freedom of expression, have clear and immediate benefits.”

“This type of exchange contributes to our professional improvement, something so necessary for every creator,” she says.

They hope to travel to the UK in October to spend time with Index on Censorship and take part in an art residency at Metal Culture. In November they will attend the Creative Time Summit in Miami.

“To be involved in different artistic experiences, activism and the debate about Cuban reality internationally will not only help visibility of our and other projects by independent organisations that are carried out in Cuba in the contemporary world but will contribute to dismantling the image of a government that continues to repress with impunity all who criticise or oppose it,” Nuñez says.

The increased attention hasn’t always been positive, however. “We feel that persecution has become stronger, something that was already accentuated by the work the precedes us and that we continue to do,” Otero Alcantara says.

“It’s a very peculiar moment in Cuban history: Fidel Castro’s generation is dying, the utopia of building the New Man is only visible in the school books. The Cuban, even if he does not want to know about politics, he does not want to go back to a ‘special period’ without water, without electricity, without food, without clothes,” he adds. “This context becomes more vulnerable with the incoming government, that’s why we must fight with all our strength, to demand the freedoms and rights that the Cuban deserves; and for this reason all platforms are indispensable.”

What remains is to continue working. “Right now we are engaged in a campaign against Degree 349 that makes art an offence,” Otero Alcantara says. “We must mobilise the artists and let them see how damaging this law will be for everyone, and the support of artists internationally will greatly help our cause.”

To be successful, they will have to leave their comfort zone, Nuñez says. “We must be aware that the world is built by people like us, not any government, that will make the system end up fracturing completely, as it no longer has the support of more than 60 years ago, no matter how hard they try to simulate in official speeches and marches.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1534853032357-5b1cf1d0-b959-3″ taxonomies=”7874″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

13 Aug 2018 | Americas, Artistic Freedom, Awards, Cuba, Fellowship, Fellowship 2018, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Cuban authorities arrested artists Yanelyz Nuñez and Luis Manuel Otero Alcantara from Otero Alcantara’s home sometime before 6:30am on Saturday 11 August for their role in organising a concert against Decree 349, a law allowing the government to sanction what art can be displayed or exchanged.

The pair are members of the Cuban artists collective the Museum of Dissidence, winners of the 2018 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards Fellowship for Art.

In a series of Facebook posts early that morning, friends and family said they didn’t know their whereabouts or what happened to them, stating that they had “disappeared”. Authorities denied knowing where they were.

It wasn’t until their release at 9:36pm that it was clear what had happened to them. During their time in detention, they were beaten and interrogated. Upon release, Otero Alcantara said: “Tomorrow we will continue the fight against the Degree 349.”

https://www.facebook.com/100014484485777/videos/439322859893860/?id=100014484485777&hc_ref=ARTkpBsSsWCxH2UFSnZDqPNuGBLHANFYaZ7uRKiRY55loJSDJPfAJvgxXpP416EHL0g

The meeting place for the concert was Otero Alcantara’s home, but when artists began arriving at around 8:50am they found the street had been blocked by police, who began beating participating artists, 30 of whom were also arrested. While this was happening police had surrounded the home and were intimidating Luis Manuel’s mother.

“We stand in solidarity with the brave artists and activists who, despite clear repression, stand up for fundamental human rights of Cubans,” Perla Hinojosa, fellowships and advocacy officer at Index on Censorship, said. “Arrests, violence and intimidation should never be responses to self-expression, and we call for such acts of censorship to stop. Any law that makes art a crime is unjust and we urge our supports to sign the petition against Decree 349.”[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Index works with the winners of the Freedom of Expression Awards Fellowship to help them achieve goals through a 12-month programme of capacity building, coaching and strategic support.

Through the fellowships, Index seeks to maximise the impact and sustainability of voices at the forefront of pushing back censorship worldwide.

Learn more about the Freedom of Expression Awards Fellowship.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Index encourages an environment in which artists and arts organisations can challenge the status quo, speak out on sensitive issues and tackle taboos.

Index currently runs workshops in the UK, publishes case studies about artistic censorship, and has produced guidance for artists on laws related to artistic freedom in England and Wales.

Learn more about our work defending artistic freedom.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1534159774557-297bf371-9804-2″ taxonomies=”23772″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

3 Aug 2018 | Artistic Freedom, Awards, Cuba, Fellowship, Fellowship 2018, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_media_grid grid_id=”vc_gid:1533806465014-9fa23910-6976-8″ include=”101950,101948,101949,101952,101947,101951″][vc_column_text]To an outsider, the most startling part of artist Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara’s arrest on 21 July for attempting to protest on the Capitol steps in Havana was the passivity, bordering on fearful ignorance, of his fellow Cubans at the scene. When he shouted and resisted, there was no response. When officers forced his head back to get him into the car, no one batted an eye.

Such is a reality Otero Alcántara and Yanelyz Nuñez, founders of the 2018 Index award-winning Museum of Dissidence, and the independent art community are working to change for the millions of Cubans whose freedom of expression remains severely constrained in the post-Castro era. Describing the challenges modern Cuba faces, Alcántara and Nuñez said “there are two political extremes that fail to dialogue and, in the background, that people are confused, apathetic, saturated with politics, and repressed by fear.”

As Index fellowships and advocacy officer Perla Hinojosa says, “When your freedoms are limited for so long, it becomes natural that when you try to express yourself in a different manner, you are stopped by authorities, so I’m assuming that the Cuban people are desensitised.”

By covering themselves in excrement and demanding “free art,” the artists planned to emphasise that “independent artists are shit for the Cuban state” as Otero Alcántara said after two days’ imprisonment and beatings. He added that they are portrayed as dissidents and lack a platform to engage with the public, much less the government, on legislation like Decree 349, a harsh new law allowing the government to sanction what art can be displayed or exchanged in private settings. Otero Alcántara believes it is “a very clear response” to the Museum of Dissidence’s independent art biennial, held in May despite government attempts to derail it.

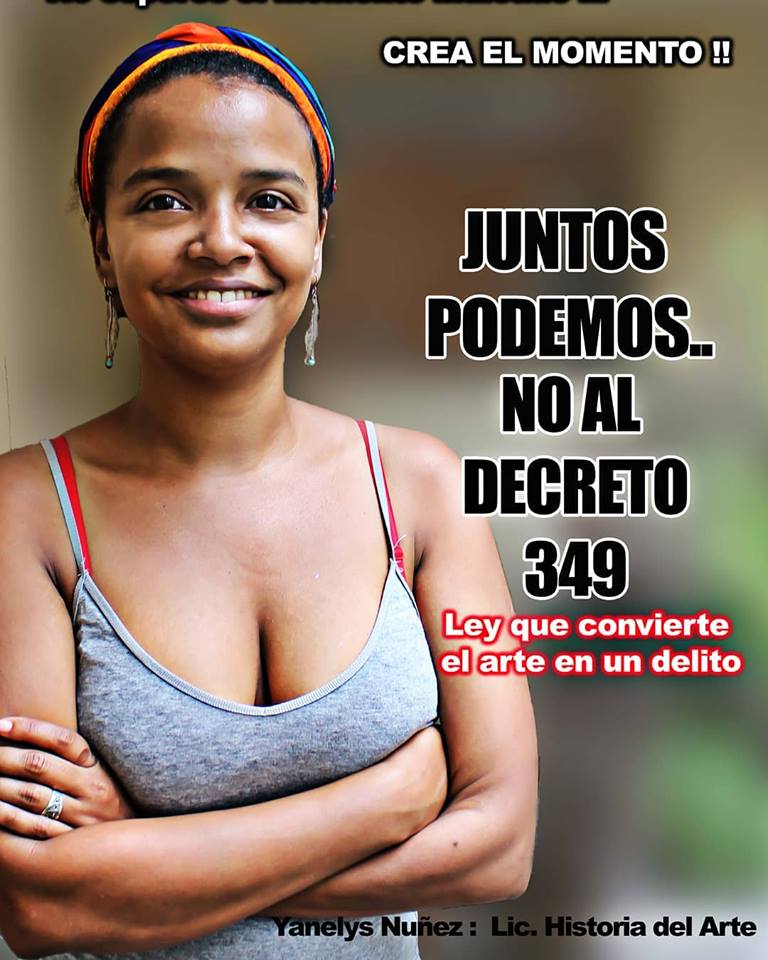

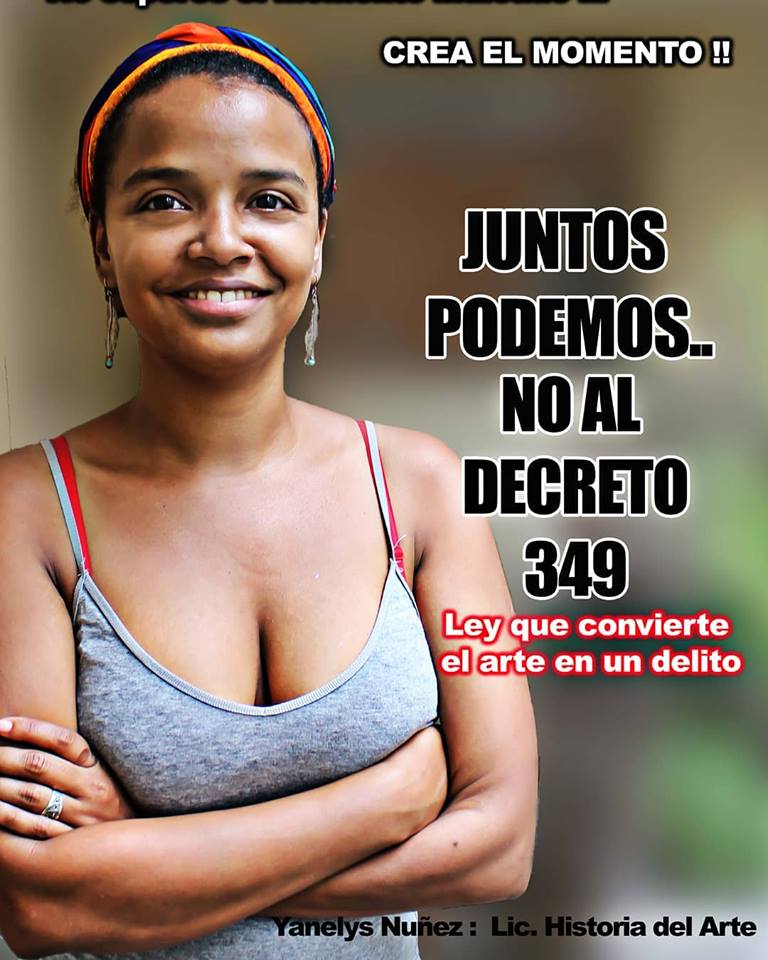

While only Nuñez could carry out the protest and demand a meeting with the minister of culture regarding Decree 349, in its aftermath, the artists catalysed a movement of peaceful resistance, digital campaigning and public dialogue to draw national attention to the law and culture of artistic censorship in Cuba. Nuñez, Otero Alcántara and Amaury Pacheco and Iris Ruiz, who were also arrested, have taken the protest to social media, using the hashtags #NOALDECRETOLEY349 (#NOTODECREELAW349) and #artelibre (#freeart) on their Facebook page representing Cuba’s independent artists.

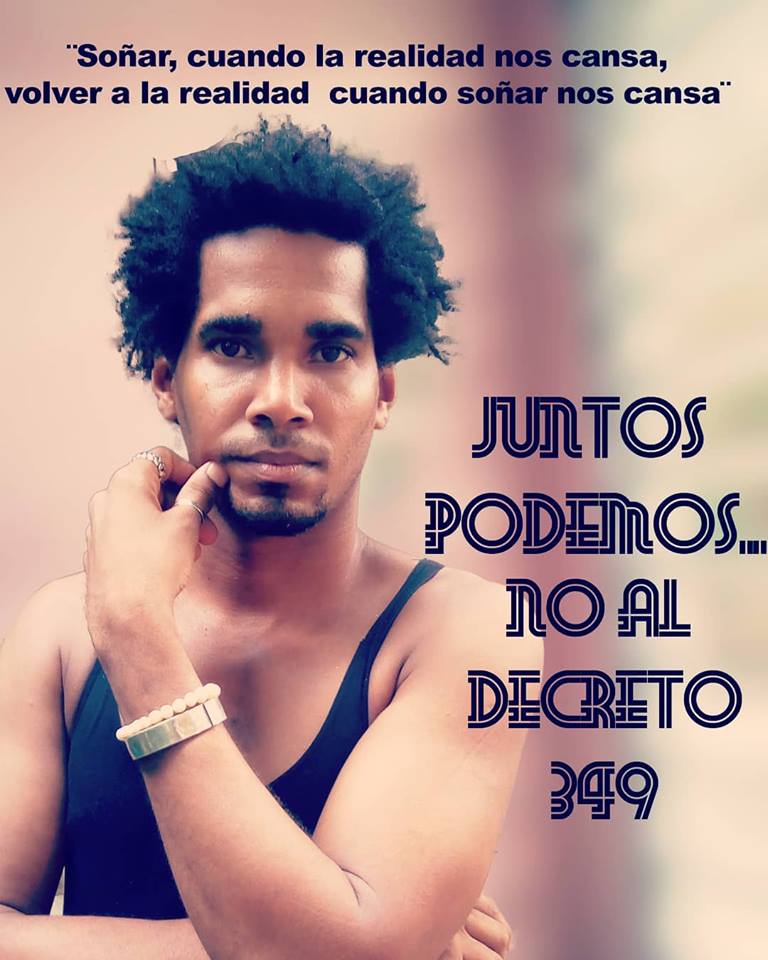

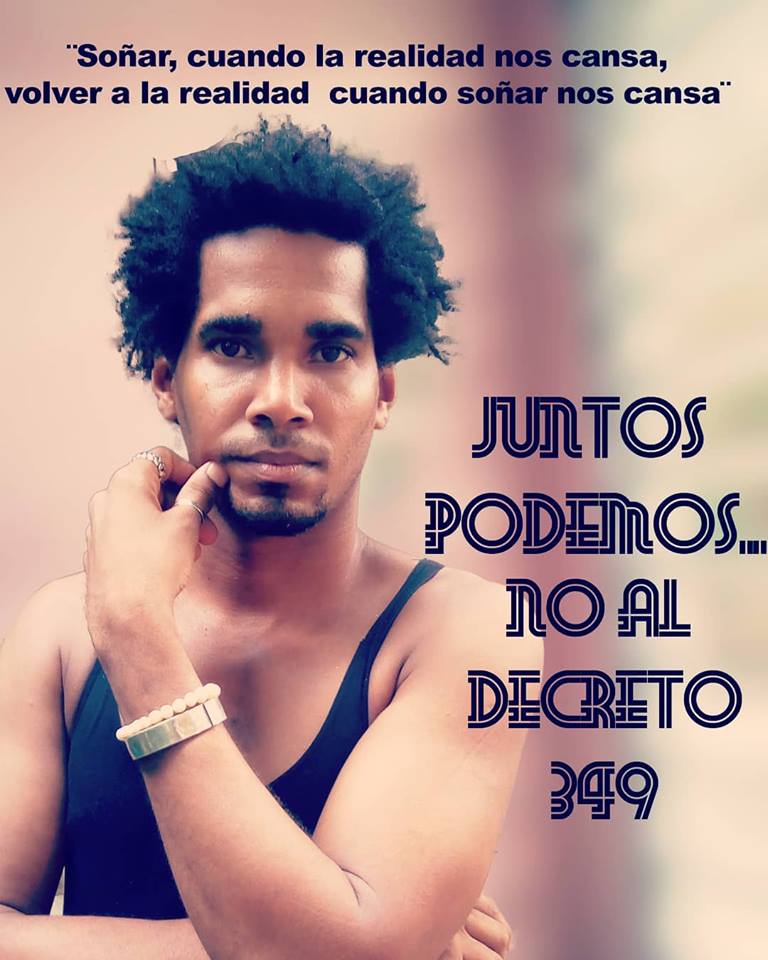

Pacheco is assembling a gallery of Cuban and international artists endorsing the campaign’s phrase: “together we can… no to Decree 349, the law that converts art into a crime.” Featured visual and performing artists like Damián Valdéz Dilla and René Rodríguez tell Cubans that “you are stronger than you think” and “don’t count the days… make sure your days count.” Such messages serve to invigorate a nation with a culture deeply rooted in the suppression of unsanctioned ideas. In his profile, Otero Alcántara encourages the public to “dream when reality tires us, to return to reality when dreaming tires us.”

Hinojosa believes “that this work embodies what meaningful activism against censorship looks like. You can be arrested and threatened but you know you have rights and are willing to stand up for them. They are creating dialogue around the issue for the betterment of themselves and their communities.”

Apart from digital activism, the artists are hosting a public debate in the first week of August. The participating independent artists and journalists have raised concerns that Decree 349 offers a “large margin of action for Cuban censors.” Their objective is to include artists from Cuba and the international community in the conversation and propose a cultural policy that is more considerate of artistic expression. Alcántara and Nuñez believe that “We belong to a generation that wants urgent improvements. A generation that, although it has no political culture, knows what it wants.”

Hinojosa says “Index aims to amplify fellows’ work so that it doesn’t go unseen and provide international support for their activism. This is essential to pressure the government and create dialogue with the community, to tell the Cuban people that it is important to speak out.”

Do you agree with the Museum of Dissidence that artists in Cuba should not be criminalised for their work? If so, please sign their petition against Decree 349.[/vc_column_text][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/-6JnYDCLKIE”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Index encourages an environment in which artists and arts organisations can challenge the status quo, speak out on sensitive issues and tackle taboos.

Index currently runs workshops in the UK, publishes case studies about artistic censorship, and has produced guidance for artists on laws related to artistic freedom in England and Wales.

Learn more about our work defending artistic freedom.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Index works with the winners of the Freedom of Expression Awards Fellowship to help them achieve goals through a 12-month programme of capacity building, coaching and strategic support.

Through the fellowships, Index seeks to maximise the impact and sustainability of voices at the forefront of pushing back censorship worldwide.

Learn more about the Freedom of Expression Awards Fellowship.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1533806465027-3ff50ed2-b280-7″ taxonomies=”7874, 23772″][/vc_column][/vc_row]