Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

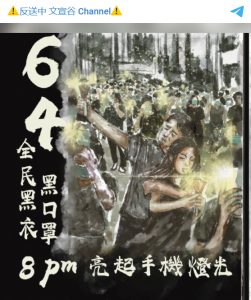

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] As you scroll through your Telegram feed, one image jumps out.

As you scroll through your Telegram feed, one image jumps out.

It shows crowds of young Hong Kongers, all dressed in black, at a protest, holding their smartphones aloft like virtual cigarette lighters from a Telegram channel called HKerschedule.

The image is an invitation for young activists to congregate and march to mark the anniversary of the Tiananmen massacre on 4 June. Wearing black has been a form of protest for many years, which has led to suggestions that the authorities may arrest anyone doing so.

Calls to action like this have migrated from fly posters and other highly visible methods of communication online.

Secure messaging has become vital to organising protests against an oppressive state.

Many protest groups have used the encrypted service Telegram to schedule and plan demonstrations and marches. Countries across the world have attempted to ban it, with limited levels of success. Vladimir Putin’s Russia tried and failed, the regimes of China and Iran have come closest to eradicating its influence in their respective states.

Telegram, and other encrypted messaging services, are crucial for those intending to organise protests in countries where there is a severe crackdown on free speech. Myanmar, Belarus and Hong Kong have all seen people relying on the services.

It also means that news sites who have had their websites blocked, such as in the case of news website Tut.by in Belarus, or broadcaster Mizzima in Myanmar, have a safe and secure platform to broadcast from, should they so choose.

Belarusian freelance journalist Yauhen Merkis, who wrote for the most recent edition of the magazine, said such services were vital for both journalists and regular civilians.

“The importance of Telegram has grown in Belarus especially due to the blocking of the main news websites and problems accessing other social media platforms such as VK, OK and Facebook after August 2020,” he said.

“Telegram is easy to use, allows you to read the main news even in times of internet access restrictions, it’s a good platform to quickly share photos and videos and for regular users too: via Telegram-bots you could send a file to the editors of a particular Telegram channel in a second directly from a protest action, for example.”

The appeal, then, revolves around the safety of its usage, as well as access to well-sourced information from journalists.

In 2020, the Mobilise project set out to “analyse the micro-foundations of out-migration and mass protest”. In Belarus, it found that Telegram was the most trusted news source among the protesters taking part in the early stages of the demonstrations in the country that arose in August 2020, when President Alexander Lukashenko won a fifth term in office amidst an election result that was widely disputed.

But there are questions over its safety. Cooper Quintin, senior security researcher of the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), a non-profit that aims to protect privacy online, said Telegram’s encryption “falls short”.

“End-to-end encryption is extremely important for everyone in the world, not just activists and journalists but regular people as well. Unfortunately, Telegram’s end-to-end encryption falls short in a couple of key areas. Firstly, end-to-end encryption isn’t enabled by default meaning that your conversations could be intercepted or recovered by a state-level actor if you don’t enable this, which most users are not aware of. Secondly, group conversations in Telegram are never encrypted [using end-to-end encryption], lacking even the option to do so, unlike other encrypted chat apps such as Signal, Wire, and Keybase.”

A Telegram spokesperson said: “Everything sent over Telegram is encrypted including messages sent in groups and posted to channels.”

This is true; however, messages sent using anything other than Secret Chats use so-called client-server/server-client encryption and are stored encrypted in Telegram’s cloud, allowing access to the messages if you lose your device, for example.

The platform says this means that messages can be securely backed up.

“We opted for a third approach by offering two distinct types of chats. Telegram disables default system backups and provides all users with an integrated security-focused backup solution in the form of Cloud Chats. Meanwhile, the separate entity of Secret Chats gives you full control over the data you do not want to be stored. This allows Telegram to be widely adopted in broad circles, not just by activists and dissidents, so that the simple fact of using Telegram does not mark users as targets for heightened surveillance in certain countries,” the company says in its FAQs.

The spokesperson said, “Telegram’s unique mix of end-to-end encryption and secure client-server encryption allows for the huge groups and channels that have made decentralized protests possible. Telegram’s end-to-end encrypted Secret Chats allow for an extra layer of security for those who are willing to accept the drawbacks of end-to-end encryption.”

If the app’s level of safety is up for debate, its impact and reach is less so.

Authorities are aware of the reach the app has and the level of influence its users can have. Roman Protasevich, the journalist currently detained in his home state after his flight from Greece to Lithuania was forcibly diverted to Minsk after entering Belarusian airspace, was working for Telegram channel Belamova. He previously co-founded and ran the Telegram channel Nexta Live, pictured.

Nexta’s Telegram page

Social media channels other than Telegram are easier to ban; Telegram access does not require a VPN, meaning even if governments choose to shut down internet providers, as the regimes in Myanmar and Belarus have done, access can be granted via mobile data. Mobile data is also targeted, but perhaps a problem easier to get around with alternative SIM cards from neighbouring countries.

People in Myanmar, for instance, have been known to use Thai SIM cards.

The site isn’t without controversy, however. Its very nature means it is a natural home for illicit activity such as revenge porn and use by extremists and terror groups. It is this that governments point to when trying to limit its reach.

China’s National Security Law attempts to censor information on the basis of criminalising any act of secession, subversion, terrorism, and collusion with external forces, the threshold for which is extremely low. It has a particular impact on protesters in Hong Kong. Telegram was therefore an easy target.

In July 2020, Telegram refused to comply with Chinese authorities attempting to gain access to user data. As they told the Hong Kong Free Press at the time: “Telegram does not intend to process any data requests related to its Hong Kong users until an international consensus is reached in relation to the ongoing political changes in the city.”

Telegram continues to resist calls to share information (which other companies have done): it even took the step of removing mobile numbers from its service, for fear of its users being identified.

Anyone who values freedom of expression and the right to protest should resist calls for messaging platforms like Telegram to pull back on encryption or to install back doors for governments. When authoritarian regimes are cracking down on independent media more than ever, platforms like these are often the only way for protests to be heard

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also want to read” category_id=”581″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”116543″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]A popular poet and comedian, and a women’s rights campaigner who co-founded Myanmar’s independent Mizzima news channel are the latest in Myanmar to fall foul of the military junta.

The military, led by General Min Aung Hlaing, has recently targeted poets, comedians and celebrities in order to silence protest against its power grab following democratic elections last November in which Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy party won a landslide victory.

The miltary authorities recently published a list of 120 celebrities wanted for arrest, some of whom have since been detained.

Popular comedian, poet, actor and director Maung Thura, known commonly as Zarganar, was arrested and detained on 6 April without charge.

Zarganar spoke to Index in 2012, a year after his release from an earlier 59-year prison sentence imposed in 2008 by the former military dictatorship in the country.

In the article, he describes his time in prison and told Index: “Freedom of speech and freedom of expression is very important for our country, for openness and transparency.”

“Over the 40 years [of the last military regime], we were living in a dark room. People could not see us,” he said. “Free art, free thought, freedom. It is very important.”

Paing Takhon, a 24-year-old actor who had expressed support for the protests, has also been detained.

The detained are perhaps the lucky ones.

Poet K Za Win was killed on 3 March by Myanmar’s security forces during protests in Monywa. On the same day, footage of bodies being dragged through the street by army personnel surfaced online.

Meanwhile, Daw Thin Thin Aung, a journalist and women’s rights activist who co-founded the banned independent news channel Mizzima in 1998, has also been detained by the Tatmadaw military.

Mizzima lost its licence to broadcast in early March along with other broadcasters Khit Thit Media, Democratic Voice of Burma (DVB), 7 Day and Myanmar Now. Despite this, Mizzima has continued its coverage of the violent arrests, shootings and other actions taken by security forces against both citizens and journalists online.

Former Mizzima journalist U James Pu Thoure has also been detained by the authorities, continuing General Min Aung Hlaing’s attack on journalists reporting on protests in the country against the coup.

Mizzima editor-in-chief Soe Myint said in a statement: “Mizzima Media is deeply concerned to learn that Daw Thin Thin Aung and U James Pu Thoure, former members of Mizzima, have been detained without charges.”

Myint said that both Thin Thin Aung and Pu Thoure had formally left the organisation since the coup of 1 February 2021.

Thin Thin Aung had previously worked as a journalist for the BBC while in exile in India. As well as her journalism, she spent many years campaigning for women’s rights in Burma, also founding the Women’s League of Burma (WLB).

Of her detainment, the WLB said “We are extremely concerned about the life and safety of Thin Thin Aung. We urge the international community to press the military coup council for the immediate release of Thin Thin Aung and other detained activists.”

Concerns have also been raised over Thin Thin Aung’s health, particularly as prison conditions in the country are notoriously poor. Mizzimia’s Soe Myint said she had been unwell for some time and had withdrawn from active working life prior to leaving Mizzima.

Since the coup, many journalists have been arrested and charged under Section 505(a) of the country’s penal code which makes it a crime to publish any “statement, rumour or report”, “with intent to cause, or which is likely to cause, any officer, soldier, sailor or airman, in the Army, Navy or Air Force to mutiny or otherwise disregard or fail in his duty”, essentially making criticism of the military government impossible.

According to Myanmar’s Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (AAPP), as of 9 April, 40 journalists had been arrested of which 31 have been detained and sentenced. It said that seven other journalists facing arrest warrants remain in hiding.

The AAPP says that the total number of people killed in Myanmar since the coup is 614. In the same period, more than 2,850 people have been arrested or detained without charge.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also want to read” category_id=”38″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Ma Kyal Sin aka Deng Jia Xi aka Angel (photo: Facebook)

Everything will be OK…

I really hope it is. But this week has been heartbreaking and it’s been women who have featured in the news paying the ultimate price for their beliefs, as they have stood tall against tyrants, as they refused to be silenced, as they demanded their rights and their freedoms. Brave, inspirational women. Women who were doing their bit to make our world just a little bit fairer, a little freer, a little better informed.

It’s hard to read the headlines. Three women journalists murdered in Afghanistan. A teenager among the 38 dead in Myanmar.

But it’s even harder to think about the reality behind the headlines. Of the person no longer with us, of the family grieving and the friends who are scared. The only thing we can really offer them as they grieve is our support and solidarity. We must bear witness, we must tell their stories, so that the world knows what happened to their loved ones. Our job is to make sure that the tyrants (whoever they are) don’t win and that they are ultimately held accountable.

So, we must not forget them. We have a responsibility to celebrate their lives, to know who they were. We need to know their stories.

Ma Kyal Sin, was known to her friends and family as Angel. A dancer from a family who just wanted to live in a democratic state. A teenager wearing a t-shirt which said “Everything Will Be OK”.

On Wednesday, she was shot dead by the police on the streets of Myanmar, while on a peaceful protest. She was one of 38 who died this week protesting against the military coup.

Mursal Wahidi, 23. Mursal had just started her dream job, that of being a journalist at the local TV station in Eastern Afghanistan (along with Sadia and Shahnaz). She was gunned down as she left her office on Wednesday.

Sadia Sadat, 21, worked at the same station in the dubbing department. Sadia was on her way home in a rickshaw when she and her colleague, Shahnaz, were ambushed and killed by a gunman on Wednesday evening near their homes.

Shahnaz Raufi, 21, who had fought for her right to be educated and who dreamed of going to university was murdered with Sadia as they travelled home together on Wednesday. Islamic State have claimed responsibility of these assassinations of young women. Women determined to be part of a free press.

On Monday, we mark International Women’s Day. This year the theme is Choose to Challenge. These women chose to challenge the status quo. They chose to stand up for their rights. They chose to believe in a better future.

In their memory – for Angel, Mursal, Sadia and Shahnaz, we need to choose to challenge tyranny wherever we see it. And we need to choose to remember them as the inspirational women they so clearly were.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also want to read” category_id=”41669″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”116336″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]The new military junta in Myanmar is continuing to assault and jail journalists as it progresses with its bloody coup.

At least 26 journalists have been arrested since Min Aung Hlaing seized power on 1 February and at least ten have been charged under section 505(a) of Myanmar’s penal code.

Two of the journalists, MCN TV News reporter Tin Mar Swe and The Voice’s Khin May San, have been granted bail but the remaining eight are still detained in the notorious military-run Insein prison in Yangon, known as “the darkest hell-hole” in the country and a byword for torture, abuse and inhumane conditions for inmates.

Section 505(a) makes it a crime to publish any “statement, rumour or report”, “with intent to cause, or which is likely to cause, any officer, soldier, sailor or airman, in the Army, Navy or Air Force to mutiny or otherwise disregard or fail in his duty”, essentially making criticism of the military government impossible.

Reporters are particularly vulnerable during protests. Myo Min Htike, former secretary of the Myanmar Journalist Association, recently told Index that journalists are being targeted across the country, particularly if they have covered protests against the coup and many have fled in fear for their lives and liberty.

Credible reports from the country show the dangers facing reporters covering the protests. Shin Moe Myint, a 23-year-old freelance photo journalist was severely beaten and arrested by policemen while she covered a protest in Yangon on 28 February.

Democratic Voice of Burma (DVB) journalist Ko Aung Kyaw live-streamed a violent arrest in which, according to reports by The Irrawaddy, he had stones thrown through his window and police officers firing threateningly into the air when asked if they had obtained a warrant to enter his premises.

Aung Kyaw could “be heard shouting that a stone injured his head and appealing to neighbours for help before the security forces broke into his house and arrested him”.

Thein Zaw, covering the protests for Associated Press, has been charged with violating public law while Ma Kay Zon Nway of Myanmar Now and Aung Ye Ko of 7 Days News have also been arrested.

Others still detained include the journalists Hein Pyae Zaw, Ye Myo Khant, Ye Yint Tun, Chun Journal chief editor Kyaw Nay Min and Salai David of Chinland Post.

Sit Htet Aung of the Myanmar Times, who took the picture above, was one of the lucky ones who managed to escape a beating and detention.

Use of section 505(a) shows an automatic crackdown on criticism of the military regime and since the coup, the junta has implemented a number of problematic legislation changes which could easily be used against journalists in the country.

According to Amnesty International: “Courts routinely convict individuals under this section without evidence establishing the requisite intent or a likelihood that military personnel would abandon their duty as a result of the expression.”

“In practice, the section has often been used to prosecute criticism of the military – expression protected by international human rights law.”

The law has since been amended, meaning anyone charged under it can be arrested without a warrant and it is no longer a bailable offence, thus any future arrests – which are likely – will find journalists in Myanmar detained with little hope of an immediate reprieve.

The same amendments apply to 124(a) of the penal code, which previously made anti-government comments illegal.

Journalists also rely heavily on the internet to publish their stories, but amendments to the Electronic Transactions Law allow law enforcement to harvest the personal data of anyone deemed to be in breach of a cyber-crime, or – more broadly – those critical of the regime online.[/vc_column_text][three_column_post title=”You may also want to read” category_id=”38″][/vc_column][/vc_row]