17 Aug 2017 | Bahrain, Bahrain News, Middle East and North Africa, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Back Row from left: Adam Rajab, Malak Rajab and Nabeel Rajab. Front Row from left: Sumaya Rajab and Zainab Alkhawaja. (Photo: Adam Rajab)

Human rights defenders often confront obstacles that make their work difficult. This is especially true in Bahrain, where the Sunni monarchy and government have been bent on silencing all opposition ever since the Arab Spring when tens of thousands of Bahraini citizens protested for democratic reform.

In recent months, the nation’s only independent news outlet, Al Wasat, was shuttered and prominent human rights activist Nabeel Rajab was sentenced to two years in prison for “spreading fake news”.

The families of activists suffer along with their loved ones and are often targeted with official harassment: detention, loss of employment, beatings and harassment. Each case is an individual story of a struggle for freedom.

A result of actions

Members of Sayed Ahmed Alwadaei’s family have been harassed and detained due to his ongoing campaigning for democracy and human rights in Bahrain. Most recently his mother-in-law and brother-in-law were detained while Alwadaei attended the United Nations Human Rights Council in March.

Alwadaei, director of advocacy at the Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy, is no stranger to detention: he was arrested twice in 2011 and served a six-month sentence in a Bahraini jail. He found asylum in the UK in July 2012. In February 2015, Alwadaei was among 72 Bahraini citizens to be stripped of their citizenship.

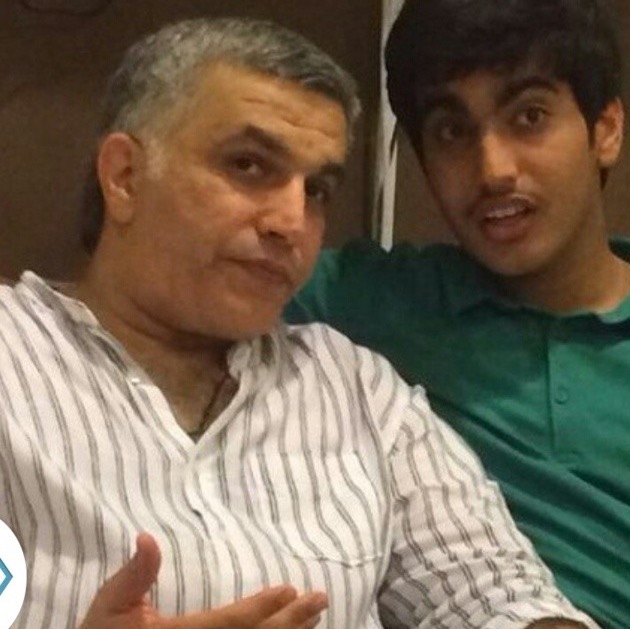

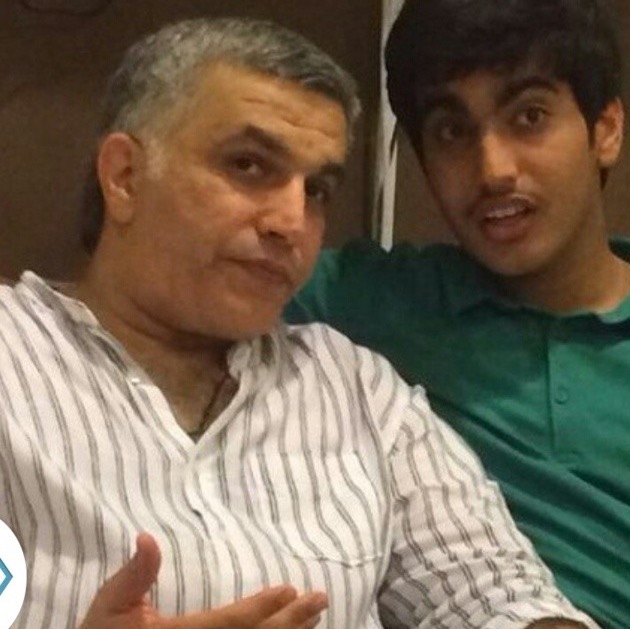

Sayed Ahmed Alwadaei with his son Yousif (Photo: Moosa Satrawi)

In October 2016, Alwadaei’s wife and infant son Yousif also faced official harassment as they tried to leave Bahrain to join Alwadaei in the UK. His wife was arrested at the airport and held overnight, during which time she was ill-treated. It was not until a few months later that she and her son were able to leave the country.

Other members Alwadaei’s family, including his sister, have also faced interrogations.

When asked how he continues campaigning under these circumstances, Alwadaei told index: “We can only get through this by sticking together and staying strong. It’s important to have a supportive family. The potential for arrest and torture is something they know and have to be willing to sacrifice.”

He added that he is balancing his efforts to get his mother-in-law out of prison while continuing his work in activism. “It’s hard but this is the right thing to do.”

“The oppression or torture aims to do one thing: to break your will because you’re not ready for the consequences,” Alwadaei said. “This is the state they want to leave you in. They want you to be broken and this is why we keep going.”

A life-long struggle

Maryam Al-Khawaja has been preparing for and participating in the struggle for human rights her entire life.

As a young child growing up in Denmark, she and her three sisters attended an English-speaking school, but the Al-Khawaja family knew they were only in the country temporarily. Her mother and father had been exiled for speaking out in Bahrain.

At a very young age, she remembers her parents asking her and her siblings before bed: “What have you done today to make the world a better place?” She told Index that her father wouldn’t help them answer the question because he wanted them to think about how the world could be. She remembers dinner conversations alive with politics and philosophical discussion about whether having false hope or no hope was better.

Around the 7th or 8th grade, Al-Khawaja knew wanted to be like her father when she grew up; she wanted to be an activist.

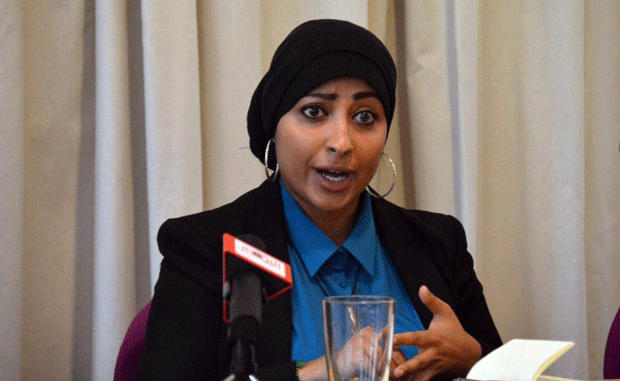

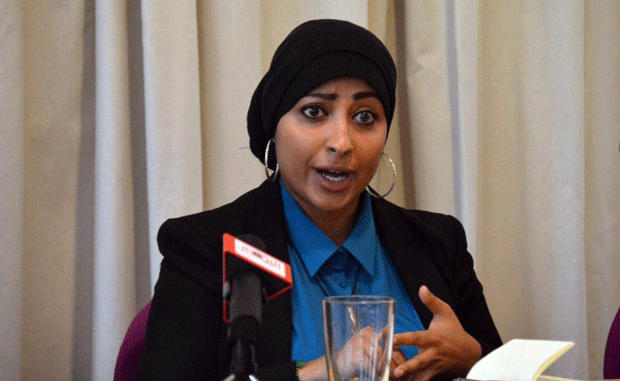

Maryam Al-Khawaja (Photo: David Coscia for Index on Censorship)

Al-Khawaja was 14 when her family returned to Bahrain in 2001. She recalls thinking her family was ready to take on the challenges and that the people of Bahrain would be ready to fight with them. But that was not the case. The country was tired of conflict and believed that the king’s promised reforms would be implemented. At the same time, activists were not popular among ordinary Bahrainis.

At college she said she was criticised by her classmates for speaking her mind about the state of their country, which caused her to lose interest in her father’s reform work. At the time, she asked him: “Why are you trying to change a situation for people who don’t want to change it for themselves?” His response was simple: “Someday you will understand.”

It wasn’t until 2011 during the Arab Spring protests that she developed a newfound respect for her father and was ashamed of herself for ever doubting him. She admits growing up in Denmark made her think fighting for human rights would be easy. When her father, along with 12 other leaders of the uprising, was arrested and sentenced to life imprisonment, she found that a life of campaigning isn’t so effortless.

During our conversation, Al-Khawaja jumped off the phone for a few minutes to take a call from her father. She had not heard from him in over three weeks and said their phone calls are always random and typically short as it is normal for the line to be cut if anything about the Bahrain government or any activist’s work is mentioned.

Until recently, her mother and sisters in Bahrain had not seen her father since February as their requests to visit have continually been denied. Al-Khawaja has not seen her father since 2014 as there are multiple fabricated charges against her that would mean imprisonment if she returned to the country.

Since her father’s imprisonment, Al-Khawaja and her older sister Zainab have been active in the push for human rights and freedom of speech in Bahrain. She says her father has two main characteristics as an activist: a fierce advocate and a fiery speaker. She explained that she and Zainab are the two parts to that whole: Al-Khawaja as the advocate and Zainab as the speaker.

Al-Khawaja said the work of her father and her sister Zainab has been tough for her two younger sisters. One sister had the highest scores in nursing school in Bahrain and graduation seemed to promise a job. But the paperwork from the government granting her access to work never came. She’s been waiting nearly eight years without a job. Al-Khawaja said it’s difficult for her family members when they’re in jail as they have to “take care of us when we cannot take care of ourselves”.

Her mother also felt the effects of the family member’s work when she was fired from her private school teaching job where she was the head of guidance.

A cause for celebrity status never wanted

Adam Rajab realised when he was young that his father Nabeel wasn’t like other dads. “I was so confused ‘why does my father work all day, while other fathers have certain working hours?,’” he told Index.

During a holiday he asked his father to take a break for a day. His father answered: “My colleagues are in prison. I can’t stop my work because they are suffering behind bars.”

In 2006, when Rajab was nine years old, he vividly recalls seeing his father come home bleeding from his head with a swollen and bruised back. “I was shocked and terrified but my father continued protesting like nothing had happened,” he said. “This was terrifying to me but the determination and fearlessness I saw in him really inspired me.”

In 2011 Nabeel Rajab’s work became well known. He appeared on TV and was the first activist to use social media to support the revolution then sweeping Bahrain. “Wherever we went, people would stop him and start taking pictures,” Adam said, adding that the strange situation was a shock to the family. “It started to become difficult because we couldn’t enjoy a private life like we used to.”

Nabeel Rajab with his son Adam Rajab

As a leader of the movement, Rajab’s father has become a face leaders around the world recognise but do little about. For years he has been in and out of jail. On 10 July 2017 he was sentenced to two years in prison for “broadcasting fake news”.

Although no one in the family has been arrested, his mother was harassed at her government job and then fired. Rajab and his sister have also faced harassment in school.

Rajab and his father have a very close relationship so the imprisonment has not been easy. “I haven’t seen him for more than a year now and he faces more charges which probably means more prison sentences,” Rajab said. “I find it difficult to enjoy anything while he is locked up in a cell and deprived of life, but as he taught me, the spirit is always up.”

Rajab wants his father to free and for them to live like any other ordinary family, but this does not take away from how proud he is or the strength of his belief in his father’s cause.

An open ended sentence

It’s difficult to imagine the emotions these activists and their families go through on a daily basis. A psychologist from the Refer Self Counselling Psychology Practice explained to Index that having a family member with a sentence with a sure release date is one case but when trials or release dates are postponed time and time again as they are in Bahrain, it is much more difficult. “We are rational problem solvers but not good with the unpredictable.”

The psychologist explained the situation in Bahrain is unlike what most with family members behind bars will ever experience. False hope puts an even greater emotional strain on loved ones.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1503052292764-bb1a6c59-5e91-2″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

8 Aug 2017 | Bahrain, Bahrain News, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Bahraini human rights defender Nabeel Rajab (Photo: The Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy)

On 7 August, a Bahraini judge postponed a ruling until 11 September in one of the cases against human rights activist and president of the Bahrain Center for Human Rights Nabeel Rajab.

Rajab is facing trial for tweets and retweets about the war in Yemen in 2015, for which he is charged with “disseminating false rumours in time of war” (Article 133 of the Bahraini Criminal Code) and “insulting a neighboring country” (Article 215 of the Bahraini Criminal Code), and for tweeting about torture in Jau prison, which resulted in a charge of “insulting a statutory body” (Article 216 of the Bahraini Criminal Code).

This case, one of four Rajab faces, began in April 2015. The trial has been postponed 14 times since and carries a sentence of up to 15 years. During the trial Rajab’s son, Adam Nabeel Rajab, tweeted that the state lacks evidence against him.

Rajab, who was an Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Advocacy award-winner in 2012, has faced continuous persecution for his activism in Bahrain. He is currently also charged with “spreading false news and statements and malicious rumours that undermine the prestige of Bahrain and the brotherly countries of the GCC, and an attempt to endanger their relations” for a piece published in Le Monde, and “undermining the prestige of the state” for a piece he wrote in The New York Times about his detention. On 10 July, Rajab was sentenced to two years in prison for charges related to 2015 television interviews with Bahraini, Iranian and Lebanese networks which support the Bahraini opposition. Rajab was unable to appear in court due to his poor health last month, and was sentenced in his absence.

Rajab marked one year in detention on 13 June, and for much of this time has been in solitary confinement and unsanitary conditions, which have contributed to his poor health and hospitalisation[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1502191511509-ebf34e9e-b840-8″ taxonomies=”716″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

7 Aug 2017 | Bahrain, Bahrain Statements, Campaigns -- Featured, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Nabeel Rajab, BCHR – winner of Bindmans Award for Advocacy at the Index Freedom of Expression Awards 2012 with then-Chair of the Index on Censorship board of trustees Jonathan Dimbleby

The Foreign & Commonwealth Office’s silence on the sentencing of human rights figure Nabeel Rajab in Bahrain has been called “appalling” in a letter to the Foreign Secretary, signed by 17 rights groups & parliamentarians today.

The President of the Bahrain Centre for Human Rights faces trial tomorrow, 7 August, for tweeting about the Yemen war and torture in Bahrain. He faces up to 15 years. He was sentenced in absentia following an unfair trial to two years in prison for giving media interviews on 10 July. Rajab has not been allowed to speak to his family since 15 July. Rajab has been held largely in solitary confinement in the first nine months of his detention. This led to his health deteriorating in April, and he is currently recovering in the Ministry of Interior clinic.

Despite British Embassy representatives regularly attending Rajab’s trials, the 10 July sentence, which clearly violated his freedom of expression, went unremarked on for over two weeks. On 26 July, the FCO stated in response to a parliamentary question: “We note the two year sentence given to him and understand there are further steps in the judicial process, including the right of appeal.”

The letter, signed by 17 rights groups says: “It is appalling that while the FCO recognises the brave work of human rights defenders worldwide, it has turned a blind eye to the human rights abuses in Bahrain, including the reprisals against Mr. Rajab.” They raise the FCO’s Human Rights and Democracy Report, published last month, which applauds the work of human rights defenders globally and state that silence on Rajab’s case contradicts policies to support human rights defenders.

The FCO’s response evaded providing an opinion on Rajab’s sentence and compares unfavourably with its response to a previous sentence Rajab received in 2012 on similar charges related to his expression. At that time, Middle East Minister Alistair Burt stated he was “very concerned” at the sentencing of Mr. Rajab on charges related to his free expression, and added, “I have made it clear to the Bahraini authorities that the human and civil rights of peaceful opposition figures must be respected.” Burt was reshuffled out of the Foreign Office in 2013, but reappointed Middle East Minister following the June election.

The rights groups told the Foreign Secretary today: “British silence on this case contradicts FCO support for human rights defenders internationally and the FCO’s own past record on Mr. Rajab’s case. We urge you to overturn this policy of silence and support Nabeel Rajab and all human rights defenders in Bahrain … by condemning his sentence and calling on the Government of Bahrain for his immediate and unconditional release and the dropping of all pending charges against him.”

While the UK was initially silent on Rajab’s sentence, key allies of Bahrain including the United States and the European Union as well as Germany and Norway all called for Rajab’s release shortly after the ruling. The US, EU and Norway called for Rajab’s release, and Germany deplored his sentence. The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights’ office called for his unconditional release.

“The FCO’s weak language on Nabeel Rajab’s case falls in line with the UK’s overall disappointing position on free expression in Bahrain and more widely in the Gulf. Boris Johnson should call for Rajab’s immediate release and take broader steps to ensure that human rights – not just arms sales – are a priority in the UK’s relations with Bahrain and the other Gulf states”, said Rebecca Vincent, UK Bureau Director for Reporters Without Borders.

“Instead of working with civil society and human rights defenders to address systemic problems and reform in Bahrain, as it has previously committed to, the government of Bahrain continues to persecute human rights defenders like Nabeel Rajab simply for exercising their right and duty to promote and protect human rights,” said Andrew Anderson, Executive Director of Front Line Defenders.

Sayed Ahmed Alwadaei, Director of Advocacy, Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy: “Boris Johnson should be ashamed of his isolated policy, which is at total odds with the foreign policy of all Bahrain western allies and partners. True partners should speak out to their allies when they cross the line. The Bahraini government’s abuses don’t seem to matter to Boris Johnson’s Foreign Office, which only appears to be vocal against repression when it’s by governments that don’t host the Royal Navy or trade with the UK.”

The letter was signed by Article 19, English PEN, FIDH, Front Line Defenders, Index on Censorship, the Jimmy Wales Foundation, PEN International, Reporters Without Borders and World Organisation Against Torture, alongside the Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy, Americans for Democracy & Human Rights in Bahrain, Gulf Centre for Human Rights and European Centre for Democracy and Human Rights. The letter was also signed by Sue Willman, Director of Deighton Pierce Glynn, Julie Ward MEP and Tom Brake MP.

The Bar Human Rights Committee of England and Wales is also separately seeking an urgent meeting with the Foreign Secretary to raise concerns over the treatment of human rights defenders in Bahrain and about the breaches of freedom of expression and fair trial and due process in Nabeel Rajab’s case.

“The trial in absence and subsequent imprisonment of Nabeel Rajab was in flagrant breach of his rights to a fair trial process. The criminalisation of Nabeel Rajeb – for sharing an opinion – is contrary to international rights and protections of freedom of expression. Whilst Mr. Rajab’s health continues to deteriorate, due his treatment in prison, this case stands as a sad indictment of Bahrain’s attitude to citizens who voice criticism. It is not too late for proper due process to be applied in this case; this would result in Mr. Rajab’s immediate release,” said Kirsty Brimelow QC of Doughty Street Chambers.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1502100162408-9703f46f-9b77-3″ taxonomies=”716″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

21 Jul 2017 | Bahrain, Middle East and North Africa, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Index on Censorship welcomes UK foreign secretary Boris Johnson’s interest in human rights. The UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office’s 2016 Annual Human Rights Report, released on Thursday 20 July, highlights the UK’s work to promote human rights around the world and sets out a list of 30 “Human Rights Priority Countries”, including Bahrain, Iran, Russia and Saudi Arabia.

In the report preface, Johnson writes: “Human rights are not inimical to development and prosperity; the opposite is true. Freedom of speech, freedom of association, freedom to practice whatever religion you want and live your life as you please, provided you do no harm, are the essential features of a dynamic and open society.”

Index agrees wholeheartedly and acknowledges that the report features many valiant efforts, including, for the first time, a section dedicated to modern slavery – a top priority for the UK government.

But the report – issued on “take out the trash” day, the last of the parliamentary sessions before a seven-week recess – does not, as it claims, seem to aspire to the “passionate advocacy” of Charles James Fox, the British Whig statesman and anti-slavery campaigner.

Instead, Johnson offers a watered-down endorsement of human rights and his department’s understanding of advocacy is seriously flawed. To borrow the foreign secretary’s own words, this is “unthinkable for anyone inspired by the example of Charles James Fox”.

Take Bahrain, for example. While the report does go some way to criticising a handful of the country’s human rights violations, this is not done not in nearly strong enough terms, and you’d be forgiven for thinking these violations are blips in an otherwise rosy picture. This is, after all, a country which has only “restricted some civil liberties”.

“There was a mixed picture on human rights in Bahrain in 2016,” the discussion of the Persian Gulf kingdom begins. “Compared with the region, Bahrain remains progressive in women’s rights, political representation, labour rights, religious tolerance and institutional accountability.”

Firstly, this is a faulty comparison. Looking at the region as a whole serves only to make Bahrain look better than it actually is. Bahrain may have 15% representation of women in parliament, as the report highlights, but this cannot be described as progressive. As of 2014, the government of Saudi Arabia, not known for its feminism, was made up of 19.9% women.

In April 2016, a royal decree that increased the rights of women in Bahrain only passed through parliament scrutiny on a technicality. In March of that year, Bahrain detained human rights activist and blogger Zainab al-Khawaja along with her one-year-old son. She was released in May but fled the country out of fear of re-arrest.

While the report does go on to criticise the dissolving of the country’s main Shia opposition party, Al Wefaq, it remains a mystery why the report would first highlight political representation and religious tolerance as positives in Bahrain.

The country certainly does not have enough institutional accountability, and this is not something it should be commended on.

Even the brief mention of Bahraini human rights activist Nabeel Rajab, sentenced to two-years in prison just for speaking to journalists 10 days before the government’s report was released, only refers to Index award-winner as having been arrested. The sheer scale of Rajab’s case is not accounted for.

On 3 February a coalition of 21 groups and individuals, including Index on Censorship, urged Johnson to call for Rajab’s release. In the time since, the US state department has called for Rajab’s release and condemned his sentencing. The UK government so far has only “voiced its concern” in the weakest possible terms, and as yet has not acknowledged Rajab’s sentencing.

When Theresa May became prime minister of the UK, Bahrain was one of the first countries she visited. As new documents reveal, UK contractors visited the country 28 times in 12 months amid Bahrain’s ongoing human rights crackdown. In all, “UK government contractors have spent more than 650 days in Bahrain training prison guards, including officers at the notorious Jau prison where death-row inmates are held and allegedly tortured,” the Middle East Eye reported earlier this month.

The UK government appears to be in no position to heap praise on Bahrain for strengthening the rule of law, justice reform, its independent human rights institutions, prisoners’ rights and improvements at Jau.

Many more issues in the Annual Human Rights Report must be scrutinised when MPs return in September. If the Bahrain section is anything to go by, the report should be found to fall far short of being “passionate” about human rights.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1500646119465-139983e0-dcda-4″ taxonomies=”716″][/vc_column][/vc_row]