Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Mark Clifford, Kris Cheng and Benedict Rogers speak in parliament ahead of the 25th anniversary of the handover of Hong Kong

“The fear of possibly being attacked by the far-reaching Chinese Communist Party is always there.” These were the words of political activist Nathan Law. His background in peaceful activism and outspoken pro-democratic views have made him a target of the Chinese Communist Party.

Law, who is best known as one of the student leaders of the Umbrella Movement and who was the youngest legislator in Hong Kong history, fled Hong Kong in 2020, a few days before the implementation of the National Security Law (NSL). In the same year, Law was listed as one of the 100 most influential individuals in the world by Time Magazine.

Law was speaking at an event organised by Index on Censorship and The Committee for Freedom in Hong Kong inside parliament, the heart of British politics. The purpose? To highlight the actions of the Chinese government and showcase the fearmongering tactics used to manipulate and intimidate all Hong Kongers, both domestic residents and those abroad, ahead of the 25th anniversary handover of Hong Kong from British rule to Beijing rule.

The event was chaired by Index on Censorship’s Jemimah Steinfeld and hosted by Neil Coyle, a Member of Parliament. Other panellists included Mark Clifford, former editor-in-chief for both The Standard and The South China Morning Post as well as president of the Committee for Freedom in Hong Kong, Evan Fowler, a writer and researcher from Hong Kong, Benedict Rogers, the CEO of Hong Kong Watch, and Kris Cheng, a journalist who used to work at Hong Kong Free Press.

Coyle kicked it off by setting the tone of the evening’s conversation: “What we [are] discussing and hearing today in this building would guarantee the panellists’ arrests and imprisonments were they to say the same in Hong Kong today.”

The implementation of the NSL has placed a stranglehold on dissent. While the punishment for violating the law is clear — up to life in prison for some “offences”— how the Chinese government interprets and manipulates the law falls into a grey zone, leaving many Hong Kong residents in a perpetual state of fear.

The NSL was a turning point, though Clifford said that “Hong Kong was always living on borrowed time”. But he spoke of how pre-handover it wasn’t always obvious the direction China would take, as the last governor of Hong Kong, Chris Patten, had created a much more pluralistic society. Speaking of this period, Clifford said that “the Chinese rightly understood that once Hong Kong people tasted freedom and democracy, it was going to be hard to put the genie back in the bottle.”

Rogers also spoke of a time where there was still hope. “For the five years that I lived and worked in Hong Kong, those first five years after the handover, that sense of foreboding when I got there appeared to have largely receded. There was a sense that One country, Two systems, by and large, was working pretty well. Hong Kong felt pretty free.”

By the time Rogers left in 2002, however, he started to see the subtle warning signs turn increasingly more substantial. “I saw some worrying signs that made me decide after five years it was time for me to move on.”

Fowler recalled the days surrounding the Handover. “It’s now being celebrated as this great event where Hong Kong was returned to the Motherland, where all the comrades happily embraced returning to the Communist fold. I really didn’t feel that at all. The feeling that I remember was that people didn’t know what was going to happen. Taking what [Clifford] said earlier about the old colonial saying ‘borrowed place on borrowed time,’ there really was a sense of that.”

Fowler went on to share an analysis of two different eras in history. “I suppose the big transition was before 1997. No matter how things were going in Hong Kong, there was always this feeling that you didn’t know what future lay in store, and ultimately you knew that that future wasn’t to be decided by you.”

Post-1997, Fowler said the general consensus was that people believed most issues had been resolved, but that it certainly wasn’t a wonderful celebration every time. Today though the CCP is trying hard to erase any memories of protest and misgivings from the time, as we recently reported here.

Chinese propaganda is something panellist Cheng was accustomed to throughout his childhood in Hong Kong. At school, Cheng went on a “national education tour” in Beijing. Cheng said the tour was a way to influence the minds of younger generations. “The whole thing is to let you have the experience in the Chinese government and capital, to know what was going on in China, to build that identity. I called it ‘softcore propaganda.’”

Cheng used this experience as motivation for his career as editorial director at Hong Kong Free Press. It also made Cheng realise the dissimilarities between Hong Kong and China. “I don’t think, at the time, that there was some sort of Hong Kong identity in the Hong Kong people, but it actually made me feel like ‘Wait, we [Hong Kongers] are a bit different.’”

Themes of oppression and manipulation were hit on heavily throughout the event. Law argued that the “fight of Hong Kong is not only for Hong Kong people”. He believes that the democratic nations of the world must “stand at the forefront of the global resistance and pushback against the rise of authoritarianism. At the end of the day, if we cannot contain the aggression of the Chinese Communist Party, there will be no ability to make a change in Hong Kong.”

“If the case of Hong Kong can remind us how fragile freedoms and democracy are and how underprepared we have been for the past few decades, then it can remind everyone we need resources and [need] to form global alliances to heckle these dictators’ aggression,” said Law.

He urged individuals on the panel and those within the room to “not let the government forget the atrocities committed against protesters and pro-democracy movements, at least until we have gathered enough mechanisms to hold these human rights perpetrators accountable.”

You can listen to a recording of our Hong Kong event here.

Jimmy Lai Chi-Ying, Hong Kong’s 74-year-old self-made billionaire, is a dissident. His cause is freedom. For championing this cause, he has been jailed since December 2020. One of the crimes he was found guilty of was lighting a candle in public to commemorate the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, when thousands were slaughtered. His real sin, however, was publishing Apple Daily, Hong Kong’s lone voice for freedom. This voice was smothered in June 2021 with the jailing of its senior journalists.

Lai could have remained free – he has homes in Paris, London, Kyoto and Taipei – but chose to stay in solidarity with the Hong Kong democrats being prosecuted. The UK abandoned Hong Kong in 1997 on China’s promise that its seven million-plus people would have “a high degree of autonomy” with “Hong Kong people ruling Hong Kong”.

However, the democrats’ demand for China to honour this pledge was rebuffed from the start and dealt a final blow in 2020 when Beijing imposed direct rule by promulgating a vague and sweeping National Security Law along with an electoral system modelled on Iran’s that allows only handpicked candidates. Virtually all democrat leaders have since been jailed.

Lai was born in Guangzhou. He escaped communist rule at the age of 12 by stealing his way into Hong Kong, hidden in the bottom of a small fishing boat. By the time he was in his 20s, he had risen from a child labourer to owning his own business.

He started Giordano, an international clothing retailer. Along the way he learned English – initially by reading the dictionary while living in the factory where he worked – and took to the brand of free-market economics espoused by Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman. He credited his success to the freedom he enjoyed in British Hong Kong. He vows to fight for this freedom so others may have the same opportunities.

Like most Hong Kong people, Lai’s political awakening came in the spring of 1989 when a democratic movement led by students erupted in Tiananmen Square in Beijing. He was sympathetic to their aspirations and lent them support by raising money through his Giordano stores.

After communist tanks mowed down demonstrators on 4 June 1989, he dedicated himself to upholding their torch of democracy by going into publishing in Hong Kong, where the press remained free.

He first launched Next, a weekly magazine, in 1990, and then Apple Daily on the eve of Hong Kong’s transition to Chinese rule. With their bold and fiercely independent editorial stance, both publications enjoyed wide readership and were successfully “cloned” in Taiwan. As the communists tightened their grip on Hong Kong, Lai was first forced to sell his controlling interest in Giordano and then his publications were subjected to orchestrated advertising boycotts. Though financial losses piled up, Lai did not waver. Readers’ loyalty remained to the end: when Apple Daily printed its last edition of one million copies on 24 June 2021, thousands of people waited in the middle of the night for it to roll off the press.

Lai is now represented by the London-based lawyer Caoilfhionn Gallagher QC. She has called Lai “a man of courage and integrity” and vowed to “pursue all available legal remedies to vindicate Mr. Lai’s rights”.

Lai’s wife Teresa is a devout Catholic. He himself converted to Catholicism when Hong Kong came under Chinese rule. China’s communists, often godless, are known to be ruthless, but in this couple they may have met their match. Because of his faith, Lai does not seek temporal salvation. He quoted the 15th-century German priest Thomas a Kempis in a letter to a friend from prison: “If thou willingly bear the Cross, it will bear thee, and will bring thee to the end which thou seekest, even where there shall be the end of suffering; though it shall not be here.”[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]*****

Jimmy Lai has been in jail since December 2020. He has told friends and associates from his cell that he does not want to turn his “life into a lie” and willingly pays the price for upholding “truth, justice, and goodness”. He said he bears this price gladly and sees it as God’s grace in disguise. Here are excerpts from some of his prison letters.[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]‘The muted anger of the Hong Kong people is not going away’

Apple Daily published its last edition of one million copies on 24 June 2021. This was how he reacted to it from prison. While deploring what he called “this barbaric suppression”, he was weighed down with guilt that his staff were incarcerated on his account and wished he could share “the pain of the cross” they bear. He vowed to find a spiritual way to help them.

The forced closure of Apple Daily Hong Kong showed clearly what [a] shipwreck life in Hong Kong has become for them. The damage done [by] the Hong Kong government and Beijing’s legitimacy long term is much greater [than] the temporary benefit of quieting down the voice of freedom of speech.

Yes, this barbaric suppression intimidation works. Hong Kong people are all quieted down. But the muted anger they have is not going away. Even those emigrating will have it forever. Many people are emigrating or planning to.

This Apple Daily shutdown only aggravates it, making it certain to people that the hopelessness of Hong Kong is irreversible. The more barbaric [the] treatment of Hong Kong people, [the] greater is their anger, and power of their potential resistance; [the] greater is the distrust of Beijing, of Hong Kong, [the] stricter is their rule to control.

The vicious circle of suppression-anger-and-distrust eventually will turn Hong Kong into a prison, a cage, like Xinjiang. World, cry for Hong Kong people.

Pastor Lee came to visit… Told me he had visited Cheung Kim Hung, our CEO, and Lo Wai Kong, our Chief Editor. They are both being remanded. Cheung, being a devout Christian, is doing fine. But Lo, who has no faith, is miserable.

What I can do to help him? Send him a Bible? But Bible is no faith, not panacea. Maybe I should ask Cardinal Zen to visit him to see what we can do for him.

It would be disingenuous to say that by creating Apple Daily I have put him in this situation. But I do have a guilty feeling and want to share his price of his cross, which is weighing too heavily on him. There must be something I can do to help. I will not cease until I find a way.

“If we suffer courageously, quietly, unselfishly, peacefully, the things [that] wreck our outer being perfect us within, and make us. And as [we] have seen, more truly ourselves.”

‘There is always a price to pay when you put truth, justice and goodness ahead of your own wellbeing’

Lai wrote in July 2021 to console his hotel staff in Canada for their suffering during the pandemic and held out the hope that soon he could share “the coming prosperity” with them. He also updated them on his life in prison, telling them not to worry about him, though when they “pass by a church, do go in and pray for me”.

Dear Bob,

If you are worry[ing] about me, please don’t. I am keeping myself busy reading the scriptures, gospels, theology and books of the saints and their lives… Life is peaceful and edifying… There is always a price to pay when you put truth, justice, and goodness ahead of your own comfort, safety and physical wellbeing, or your life becomes a lie. I choose truth instead of a lie and pay the price. Luckily God has made this price a grace in disguise. I am so grateful.

So, don’t worry about me. However, when you pass by a church, do go in [and] pray for me. Believers and non-believers, the sun shines on you the same. So the Lord will listen to you the same. Thank you! Hope to see you soon,

Cheers,

Jimmy.

‘I am changed… I can’t see myself going back to business again’

Lai wrote to a friend, James, in September 2021, saying that, by clinging to Christ, his life in prison “is full” and spiritually “at peace”. However, he was worried about his wife, Teresa, whom he said was weighed down by grief.

James,

I am doing fine, keeping myself busy, studying gospels, scriptures, theology and books on the saints and lives and prayers, touching the fringe of Christ’s cloak to live, so to speak. Life is full and at peace. I am learning and changed a lot. Can’t see myself going back to business again. All have to depend on others.

I do worry about my wife Teresa. She has lost a lot of weight under the grief of my situation. Lucky she has God [to] abide [with] her. May God bless you all.

Cheers,

Uncle Jimmy

‘But with her prayers, she will slug it through’

In October 2021, Lai wrote to a business associate about his happiness when his family visited him. He urged him to “keep writing”.

I am doing fine here. Happy to see Teresa, Claire, Tim and Ian and my brother… Teresa looks weak and weighed down by grief. But with her prayers, she will slug it through.

I am keeping myself busy here. Spiritual study, drawing and trying to improve my English writing skill. Take care!

So sweet of you to write me. Please keep writing. May God be with you all! Cheers, Uncle Jimmy

‘If thou willingly bear the Cross, it will bring thee [that] which thou seekest… ’

In a November 2021 letter to a friend, Lai copied the following quote from the 15th-century German priest Thomas a Kempis, author of The Imitation of Christ.

“If thou willingly bear the Cross, it will bear thee, and will bring thee to the end which thou seekest, even where there shall be the end of suffering; though it shall not be here.

“If thou bear it unwillingly, thou makest a burden for thyself and greatly increaseth thy load, and yet thou must bear it.”

‘Lord, remember those who shed their blood in Tiananmen Square’

Lai was sentenced 13 months in jail for attending the vigil in Victoria Park, Hong Kong, on 4 June 2020 that marked the 31st anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre. He protested his innocence by reading the following statement in court before he was sentenced. He appealed to God to grant the young men and women who died in Tiananmen their redemption.

I did not join the 4 June vigil in Victoria Park. I lit a candle light in front of reporters to remind the world to commemorate and remember those brave young men and women who 31 years ago in Tiananmen Square put the truth, justice and goodness above their lives and died for them.

If [to] commemorate those who died because of injustice is a crime, then inflict on me that crime and let me suffer the punishment of the crime, so that I may share the burden and glory of those men and women who shed their blood on June 4th to proclaim truth, injustice and goodness.

Lord, remember those who shed their blood, but do not remember their cruelty. Remember the fruits those young men and women have borne because what they did and grant, Lord, that the fruits these young men and women have borne may be their redemption. May the power of love of the meek prevail over the power of destruction of the strong.

This article and Lai’s letters appeared in the 50th anniversary issue of Index on Censorship magazine, alongside a picture that Lai drew of Jesus Christ on the cross. They were published on 15th March 2022. Click here for options on how to see and read the article in full.

A former food delivery worker calling himself a “second-generation Captain America” and who would turn up at protests in Hong Kong with the Marvel superhero’s instantly recognisable shield has been convicted for violating the country’s national security law (NSL).

On 11 November, Adam Ma Chun-man was sentenced to five years and nine months for inciting secession by chanting pro-independence slogans in public places between August and November 2020.

Evidence cited by a government prosecutor in the court case against Ma included calls for independence he had made in interviews.

Ma becomes the second person to be found guilty under the law imposed by Beijing in July last year. He has lodged an appeal against the verdict.

The first person sentenced under the NSL was former waiter Tong Ying-kit who was jailed in late July for nine years for terrorist activities and inciting secession. Tong was accused of driving his motorcycle into three riot police on 1 July 2020 while carrying a flag with the protest slogan “Liberate Hong Kong. Revolution of our times.”

The watershed ruling on Tong has profound implications for freedom of expression and judicial independence in Hong Kong.

The “Captain America” case has further fuelled fears about the rapid erosion of the city’s room for freedom and the strength of the court in upholding civil liberties.

Like the Tong case, the Ma judgement has significant implications for related cases but the ruling has attracted far less attention. The general public reacted with indifference mixed with a feeling of futility and helplessness. It does not bode well for civil rights and liberties in the city.

The significance of the Ma case lies with the judge’s ruling on what constituted incitement.

Ma’s lawyer said Ma had no intention whatsoever of committing a crime, but was just expressing his views. Merely chanting slogans should not be deemed as a violation of the NSL, the lawyer argued. That he urged people to discuss the issue of independence in schools did not necessarily mean the result of the discussions would be a yes to independence. It could be a no.

Importantly, his lawyer argued Ma had merely expressed his personal views without giving thought of how to make it happen through an action plan. Referring to Ma’s slogan “Hong Kong people building an army”, his lawyer said it was just an empty slogan, again, without a plan.

In sentencing, judge Stanley Chan described the case as serious. He rejected the argument by Ma’s lawyer that the level of incitement in his speeches was minimal, saying Ma could turn more people into the next Ma Chun-man.

Put simply, judge Chan said that although the actual impact of Ma’s speeches in inciting others has been minimal, this was insignificant when determining whether his act constituted incitement.

This view is markedly different from the reaction of the media and the public over Ma’s political antics.

Ma had drawn the attention of journalists when he turned up in protests for obvious reasons. But no more. The lone protester neither had a sizable group of followers nor electrified the sentiments of the crowd at the scene.

The heavy sentencing of Ma will worsen the chilling effect of the national security law on freedom of expression. Importantly, it will have serious implications for a list of incitement cases currently in the process of trial.

In a statement on the sentencing, Kyle Ward, Amnesty International’s deputy secretary general said: “In the warped political landscape of post-national security law Hong Kong, peacefully expressing a political stance and trying to get support from others is interpreted as ‘inciting subversion’ and punishable by years in jail.”

With no sign of an easing of the enforcement of the law 16 months after it took effect, the international human rights group decided to shut down its local and regional offices in the city by the end of the year. They said the Beijing-imposed law made it “effectively impossible” to do its work without fear of “serious reprisals” from the Government.

Hong Kong chief executive Carrie Lam responded by saying no organisation should be worried about the national security law if they are operating legally in Hong Kong, adding Hong Kong residents’ freedoms, including that of speech, association and assembly were guaranteed under Article 27 of the Basic Law, the city’s mini-constitution.

To a lot of Hongkongers, the assurance, which is an integral part of the former British colony’s “one country, two systems” policy, is an empty promise.

The power of the national security law in curtailing freedoms in other aspects of everyday life in Hong Kong has been widely felt.

In October, the legislature rubber-stamped an amendment to the film censorship ordinance, giving powers to the authorities to ban films that are considered as “contrary to the interests of national security.” The phrase, or “red line” in the law, is much broader than the original version, which targeted anything that might “endanger national security.”

Even before the bill was passed, a number of films and documentary films relating to the 2019 protest were not allowed to be shown in public locally. They include the award-winning Inside the Red Brick Wall and Revolution of Our Times, a nominee in the 2021 Taiwan Golden Horse Film Award.

Moves to revive political censorship in film are part of the authorities’ intensified campaign against threats to national security. While targeting political activists, the net has been widened to curb what officials described as “soft confrontation” and “penetration” through films, art and culture and books.

The University of Hong Kong has called for the Pillar of Shame, a sculpture by Danish artist Jens Galschiot, to be removed from the campus, citing concern over the national security law.

On the legislative front, security minister Chris Tang has given clear reminders that more needs to be done to protect national security, pointing to crimes in Basic Law Article 23 that have not been covered in the national security law.

He has vowed to target spying activities and to plug loopholes following the social unrest in 2019. Tang cited the example that helmets and free MTR tickets were distributed free to protesters during the protests, claiming there were state-level organising behaviours, potentially by actors from outside the country.

Both the central and Hong Kong authorities have labelled the movement as a “colour revolution” with hostile foreign forces behind it, without giving concrete evidence.

In addition to spying, a bill on Article 23 will also cover theft of state secrets and links with foreign organisations. Officials gave no timetable. But it is expected to be at the top of the agenda for the new legislature, which is due to be formed after an election is held on 19 December.

Officials are also looking at introducing a law on “fake news” to eliminate what they deem as lies and disinformation, which went viral on social media during the 2019 protest. The Government and the Police claimed they were major victims of this false information.

Looking back to mid-2020 when the idea of a national security law was first mooted, officials assured Hongkongers the law would only “target a very small number of people”.

Nothing can be further from the truth.

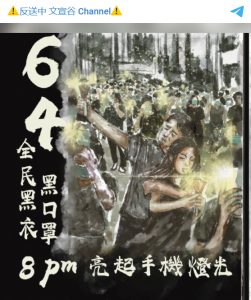

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] As you scroll through your Telegram feed, one image jumps out.

As you scroll through your Telegram feed, one image jumps out.

It shows crowds of young Hong Kongers, all dressed in black, at a protest, holding their smartphones aloft like virtual cigarette lighters from a Telegram channel called HKerschedule.

The image is an invitation for young activists to congregate and march to mark the anniversary of the Tiananmen massacre on 4 June. Wearing black has been a form of protest for many years, which has led to suggestions that the authorities may arrest anyone doing so.

Calls to action like this have migrated from fly posters and other highly visible methods of communication online.

Secure messaging has become vital to organising protests against an oppressive state.

Many protest groups have used the encrypted service Telegram to schedule and plan demonstrations and marches. Countries across the world have attempted to ban it, with limited levels of success. Vladimir Putin’s Russia tried and failed, the regimes of China and Iran have come closest to eradicating its influence in their respective states.

Telegram, and other encrypted messaging services, are crucial for those intending to organise protests in countries where there is a severe crackdown on free speech. Myanmar, Belarus and Hong Kong have all seen people relying on the services.

It also means that news sites who have had their websites blocked, such as in the case of news website Tut.by in Belarus, or broadcaster Mizzima in Myanmar, have a safe and secure platform to broadcast from, should they so choose.

Belarusian freelance journalist Yauhen Merkis, who wrote for the most recent edition of the magazine, said such services were vital for both journalists and regular civilians.

“The importance of Telegram has grown in Belarus especially due to the blocking of the main news websites and problems accessing other social media platforms such as VK, OK and Facebook after August 2020,” he said.

“Telegram is easy to use, allows you to read the main news even in times of internet access restrictions, it’s a good platform to quickly share photos and videos and for regular users too: via Telegram-bots you could send a file to the editors of a particular Telegram channel in a second directly from a protest action, for example.”

The appeal, then, revolves around the safety of its usage, as well as access to well-sourced information from journalists.

In 2020, the Mobilise project set out to “analyse the micro-foundations of out-migration and mass protest”. In Belarus, it found that Telegram was the most trusted news source among the protesters taking part in the early stages of the demonstrations in the country that arose in August 2020, when President Alexander Lukashenko won a fifth term in office amidst an election result that was widely disputed.

But there are questions over its safety. Cooper Quintin, senior security researcher of the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), a non-profit that aims to protect privacy online, said Telegram’s encryption “falls short”.

“End-to-end encryption is extremely important for everyone in the world, not just activists and journalists but regular people as well. Unfortunately, Telegram’s end-to-end encryption falls short in a couple of key areas. Firstly, end-to-end encryption isn’t enabled by default meaning that your conversations could be intercepted or recovered by a state-level actor if you don’t enable this, which most users are not aware of. Secondly, group conversations in Telegram are never encrypted [using end-to-end encryption], lacking even the option to do so, unlike other encrypted chat apps such as Signal, Wire, and Keybase.”

A Telegram spokesperson said: “Everything sent over Telegram is encrypted including messages sent in groups and posted to channels.”

This is true; however, messages sent using anything other than Secret Chats use so-called client-server/server-client encryption and are stored encrypted in Telegram’s cloud, allowing access to the messages if you lose your device, for example.

The platform says this means that messages can be securely backed up.

“We opted for a third approach by offering two distinct types of chats. Telegram disables default system backups and provides all users with an integrated security-focused backup solution in the form of Cloud Chats. Meanwhile, the separate entity of Secret Chats gives you full control over the data you do not want to be stored. This allows Telegram to be widely adopted in broad circles, not just by activists and dissidents, so that the simple fact of using Telegram does not mark users as targets for heightened surveillance in certain countries,” the company says in its FAQs.

The spokesperson said, “Telegram’s unique mix of end-to-end encryption and secure client-server encryption allows for the huge groups and channels that have made decentralized protests possible. Telegram’s end-to-end encrypted Secret Chats allow for an extra layer of security for those who are willing to accept the drawbacks of end-to-end encryption.”

If the app’s level of safety is up for debate, its impact and reach is less so.

Authorities are aware of the reach the app has and the level of influence its users can have. Roman Protasevich, the journalist currently detained in his home state after his flight from Greece to Lithuania was forcibly diverted to Minsk after entering Belarusian airspace, was working for Telegram channel Belamova. He previously co-founded and ran the Telegram channel Nexta Live, pictured.

Nexta’s Telegram page

Social media channels other than Telegram are easier to ban; Telegram access does not require a VPN, meaning even if governments choose to shut down internet providers, as the regimes in Myanmar and Belarus have done, access can be granted via mobile data. Mobile data is also targeted, but perhaps a problem easier to get around with alternative SIM cards from neighbouring countries.

People in Myanmar, for instance, have been known to use Thai SIM cards.

The site isn’t without controversy, however. Its very nature means it is a natural home for illicit activity such as revenge porn and use by extremists and terror groups. It is this that governments point to when trying to limit its reach.

China’s National Security Law attempts to censor information on the basis of criminalising any act of secession, subversion, terrorism, and collusion with external forces, the threshold for which is extremely low. It has a particular impact on protesters in Hong Kong. Telegram was therefore an easy target.

In July 2020, Telegram refused to comply with Chinese authorities attempting to gain access to user data. As they told the Hong Kong Free Press at the time: “Telegram does not intend to process any data requests related to its Hong Kong users until an international consensus is reached in relation to the ongoing political changes in the city.”

Telegram continues to resist calls to share information (which other companies have done): it even took the step of removing mobile numbers from its service, for fear of its users being identified.

Anyone who values freedom of expression and the right to protest should resist calls for messaging platforms like Telegram to pull back on encryption or to install back doors for governments. When authoritarian regimes are cracking down on independent media more than ever, platforms like these are often the only way for protests to be heard

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also want to read” category_id=”581″][/vc_column][/vc_row]