Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

London drill rapper Rico Racks has been jailed for three years for drug offences and banned from using certain words in his rap songs.

This is not the first time rappers have been told by the courts to exclude certain words from their music, and this type of legislation has been criticised by Index CEO Jodie Ginsberg.

Read the full story here

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2019/oct/21/drill-rapper-rico-racks-jailed-and-banned-from-rapping-certain-words

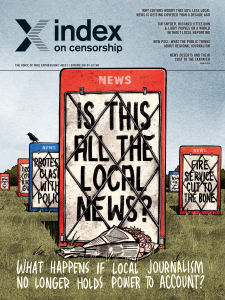

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”97% of editors of local news worry that the powerful are no longer being held to account ” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_column_text]

Ninety seven per cent of senior journalists and editors working for the UK’s regional newspapers and news sites say they worry that that local newspapers do not have the resources to hold power to account in the way that they did in the past, according to a survey carried out by the Society of Editors and Index on Censorship. And 70% of those respondents surveyed for a special report published in Index on Censorship magazine are worried a lot about this.

The survey, carried out in February 2019 for the spring issue of Index on Censorship magazine, asked for responses from senior journalists and current and former editors working in regional journalism. It was part of work carried out for this magazine to discover the biggest challenges ahead for local journalists and the concerns about declining local journalism has on holding the powerful to account.

The survey found that 50% of editors and journalists are most worried that no one will be doing the difficult stories in future, and 43% that the public’s right to know will disappear. A small number worry most that there will be too much emphasis on light, funny stories.

There are some specific issues that editors worry about, such as covering court cases and council meetings with limited resources.

Twenty editors surveyed say that they feel only half as much local news is getting covered in their area compared with a decade ago, with 15 respondents saying that about 10% less news is getting covered. And 74% say their news outlet covers court cases once a week, and 18% say they hardly ever cover courts.

The special report also includes a YouGov poll commissioned for Index on public attitudes to local journalism. Forty per cent of British adults over the age of 65 think that the public know less about what is happening in areas where local newspapers have closed, according to the poll.

Meanwhile, 26% of over-65s say that local politicians have too much power where local newspapers have closed, compared with only 16% of 18 to 24-year-olds. This is according to YouGov data drawn from a representative sample of 1,840 British adults polled on 21-22 February 2019.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” size=”xl” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”The demise of local reporting undermines all journalism, creating black holes at the moment when understanding the “backcountry” is crucial” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]The Index magazine special report charts the reduction in local news reporting around the world, looking at China, Argentina, Spain, the USA, the UK among other countries.

Index on Censorship editor Rachael Jolley said: “Big ideas are needed. Democracy loses if local news disappears. Sadly, those long-held checks and balances are fracturing, and there are few replacements on the horizon. Proper journalism cannot be replaced by people tweeting their opinions and the occasional photo of a squirrel, no matter how amusing the squirrel might be.”

She added: “If no local reporters are left living and working in these communities, are they really going to care about those places? News will go unreported; stories will not be told; people will not know what has happened in their towns and communities.”

Others interviewed for the magazine on local news included:

Michael Sassi, editor of the Nottingham Post and the Nottingham Live website, who said: “There’s no doubt that local decision-makers aren’t subject to the level of scrutiny they once were.”

Lord Judge, former lord chief justice for England and Wales, said: “As the number of newspapers declines and fewer journalists attend court, particularly in courts outside London and the major cities, and except in high profile cases, the necessary public scrutiny of the judicial process will be steadily eroded,eventually to virtual extinction.”

US historian and author Tim Snyder said: “The policy thing is that government – whether it is the EU or the United States or individual states – has to create the conditions where local media can flourish.”

“A less informed society where news is replaced by public relations, reactive commentary and agenda management by corporations and governments will become dangerously volatile and open to manipulation by special interests. Allan Prosser, editor of the Irish Examiner.

“The demise of local reporting undermines all journalism, creating black holes at the moment when understanding the “backcountry” is crucial. Belgian journalist Jean Paul Marthoz.

The special report “Is this all the local news? What happens if local journalism no longer holds power to account?” is part of the spring issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Note to editors: Index on Censorship is a quarterly magazine, which was first published in 1972. It has correspondents all over the world and covers freedom of expression issues and censored writing

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Is this all the Local News?” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2018%2F12%2Fbirth-marriage-death%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The spring 2019 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores what happens to democracy without local journalism, and how it can survive in the future.

With: Richard Littlejohn, Libby Purves and Tim Snyder[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_single_image image=”105481″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/12/birth-marriage-death/”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”The number of people listening to radio stations is on the rise, and with the arrival of podcasting this old form of media is having a rebirth, argues Rachael Jolley”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

A retro style digital microphone. Credit: Alan Levine/Flickr

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”Digital technologies have given radio a new lease of life.” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”89165″ img_size=”213×300″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/03064220100390021001″][vc_custom_heading text=”Radio waves” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F03064220100390021001|||”][vc_column_text]June 2010

Liam Hodkinson and Elizabeth Stitt compile comprehensive facts on radio usage throughout the world.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”90954″ img_size=”213×300″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064229408535741″][vc_custom_heading text=”Death by radio” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064229408535741|||”][vc_column_text]September 1994

If Rwandan genocide comes to trial, owners of Radio des Milk Collines should be head of the accused.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”89165″ img_size=”213×300″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0306422010372565″][vc_custom_heading text=”Going local” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422010372565|||”][vc_column_text]June 2010

Jo Glanville explains how radio has the most impact on the local level than any other media platform.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Free to air” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:%20https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F09%2Ffree-to-air%2F|||”][vc_column_text]Through a range of in-depth reporting, interviews and illustrations, the autumn 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores how radio has been reborn and is innovating ways to deliver news in war zones, developing countries and online

With: Ismail Einashe, Peter Bazalgette, Wana Udobang[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”95458″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/09/free-to-air/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

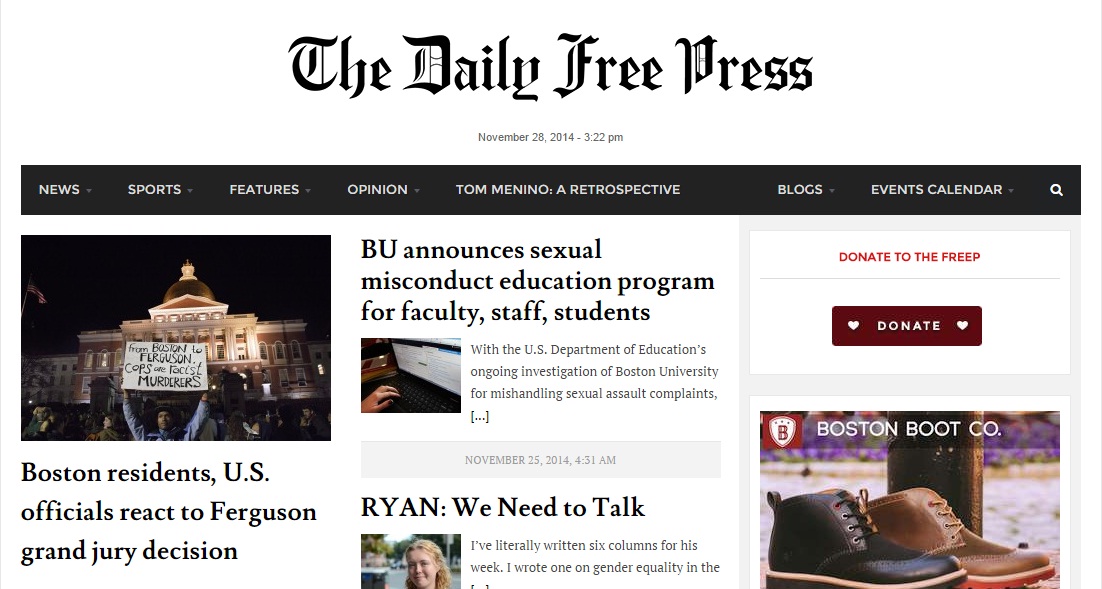

Independent student newspapers struggle in an increasingly digital world. Advertising revenue is shrinking. Budding journalists must learn how to fill the gap while maintaining news coverage free of administration censorship.

Of the more than 500 student newspapers in the US, Index spoke with two papers about their work and how they finance themselves independently.

“We really value our independent status because it allows us to be critical of the administration and be a watchdog of our university,” Kyle Plantz, editor-in-chief at Boston University’s Daily Free Press, said in an email interview.

The paper formed in 1970 after the university’s then president John Silber cut funding to two campus publications to prevent coverage of Kent State protests. As a result they merged to become the Free Press.

In recent years, Daily Free Press staff has written articles covering topics on campus such as gender neutral housing and students’ issues with the Student Activities Office, which oversees student organisations. In late 2011-2012, the paper provided extensive coverage of the arrest of two ice hockey players charged with sexual assault.

Nicole Brown, editor-in-chief at New York University’s Washington Square Press, also said her paper acts as a watchdog on the NYU administration.

“We need to be able to question our university and present information to the community,” Brown said. “We also need to be able to voice our opinions without fear of being punished for those opinions.”

The Washington Square Press keeps an open dialogue on campus through its feature, NYU Reacts. It includes students’ thoughts on topics ranging from ISIS subway threats to pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong. The paper also publishes articles on sensitive issues, such as a November 2013 piece in which NYU faculty express concern over the London campus’s rapid expansion.

Many student papers struggle to maintain steady revenue. Brown said the Washington Square Press relies on advertising, sold and managed by student staff.

“With a move toward more online content, there are more opportunities to sell ad spaces online, as well as in print,” Brown said.

For the Free Press, nearly $70,000 (£44,576.05) debt to their printers recently threatened to shutter their publication. They switched from publishing four days a week to once a week and, on 10 November, launched a crowd-sourcing campaign.

The paper surpassed their goal and raised over $82,000 in just three days, with Daily Free Press alumnus Bill O’Reilly donating $10,000 and local businessman Ernie Boch Jr. donating $50,000.

“[Reducing publication], along with cutting some other costs, we are able to continue to receive ad revenue and sustain our weekly print edition,” Plantz said. “We are assessing how we want to use [the extra funds] and what will be beneficial to our organization in the future.”

Independent newspapers must find a way to financially sustain themselves or campuses will lose reliable, student-run news.

As Plantz said, “We are one of the only outlets that allow students to have a voice, question authority, and be a place for students, faculty, staff, and the administration to come together to learn about what’s happening on campus.”

This article was originally posted 28 November on indexoncensorship.org