7 Jan 2016 | France, Mapping Media Freedom, News, Statements, United Kingdom

When I started working at Index on Censorship, some friends (including some journalists) asked why an organisation defending free expression was needed in the 21st century. “We’ve won the battle,” was a phrase I heard often. “We have free speech.”

There was another group who recognised that there are many places in the world where speech is curbed (North Korea was mentioned a lot), but most refused to accept that any threat existed in modern, liberal democracies.

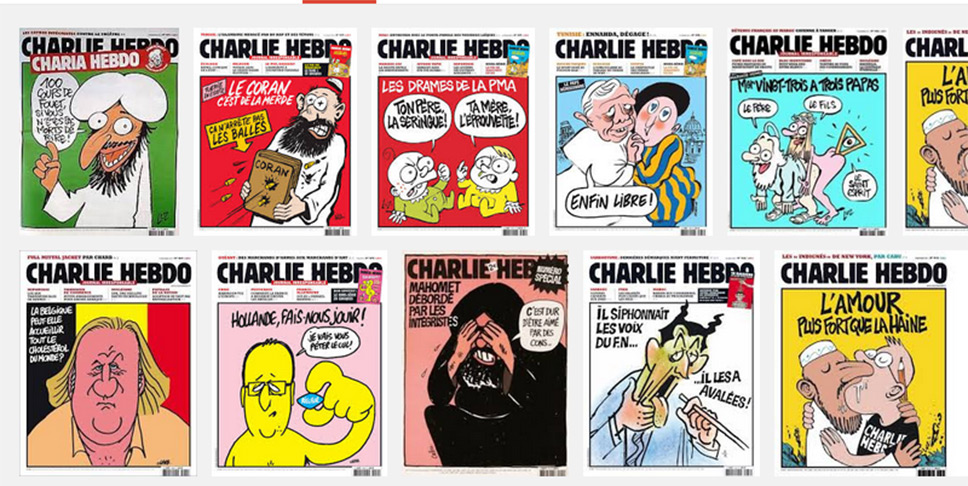

After the killing of 12 people at the offices of French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, that argument died away. The threats that Index sees every day – in Bangladesh, in Iran, in Mexico, the threats to poets, playwrights, singers, journalists and artists – had come to Paris. And so, by extension, to all of us.

Those to whom I had struggled to explain the creeping forms of censorship that are increasingly restraining our freedom to express ourselves – a freedom which for me forms the bedrock of all other liberties and which is essential for a tolerant, progressive society – found their voice. Suddenly, everyone was “Charlie”, declaring their support for a value whose worth they had, in the preceding months, seemingly barely understood, and certainly saw no reason to defend.

The heartfelt response to the brutal murders at Charlie Hebdo was strong and felt like it came from a united voice. If one good thing could come out of such killings, I thought, it would be that people would start to take more seriously what it means to believe that everyone should have the right to speak freely. Perhaps more attention would fall on those whose speech is being curbed on a daily basis elsewhere in the world: the murders of atheist bloggers in Bangladesh, the detention of journalists in Azerbaijan, the crackdown on media in Turkey. Perhaps this new-found interest in free expression – and its value – would also help to reignite debate in the UK, France and other democracies about the growing curbs on free speech: the banning of speakers on university campuses, the laws being drafted that are meant to stop terrorism but which can catch anyone with whom the government disagrees, the individuals jailed for making jokes.

And, in a way, this did happen. At least, free expression was “in vogue” for much of 2015. University debating societies wanted to discuss its limits, plays were written about censorship and the arts, funds raised to keep Charlie Hebdo going in defiance against those who would use the “assassin’s veto” to stop them. It was also a tense year. Events discussing hate speech or cartooning for which six months previously we might have struggled to get an audience were now being held to full houses. But they were also marked by the presence of police, security guards and patrol cars. I attended one seminar at which a participant was accompanied at all times by two bodyguards. Newspapers and magazines across London conducted security reviews.

But after the dust settled, after the initial rush of apparent solidarity, it became clear that very few people were actually for free speech in the way we understand it at Index. The “buts” crept quickly in – no one would condone violence to deal with troublesome speech, but many were ready to defend a raft of curbs on speech deemed to be offensive, or found they could only defend certain kinds of speech. The PEN American Center, which defends the freedom to write and read, discovered this in May when it awarded Charlie Hebdo a courage award and a number of novelists withdrew from the gala ceremony. Many said they felt uncomfortable giving an award to a publication that drew crude caricatures and mocked religion.

Index’s project Mapping Media Freedom recorded 745 violations against media freedom across Europe in 2015.

The problem with the reaction of the PEN novelists is that it sends the same message as that used by the violent fundamentalists: that only some kinds of speech are worth defending. But if free speech is to mean anything at all, then we must extend the same privileges to speech we dislike as to that of which we approve. We cannot qualify this freedom with caveats about the quality of the art, or the acceptability of the views. Because once you start down that route, all speech is fair game for censorship – including your own.

As Neil Gaiman, the writer who stepped in to host one of the tables at the ceremony after others pulled out, once said: “…if you don’t stand up for the stuff you don’t like, when they come for the stuff you do like, you’ve already lost.”

Index believes that speech and expression should be curbed only when it incites violence. Defending this position is not easy. It means you find yourself having to defend the speech rights of religious bigots, racists, misogynists and a whole panoply of people with unpalatable views. But if we don’t do that, why should the rights of those who speak out against such people be defended?

In 2016, if we are to defend free expression we need to do a few things. Firstly, we need to stop banning stuff. Sometimes when I look around at the barrage of calls for various people to be silenced (Donald Trump, Germaine Greer, Maryam Namazie) I feel like I’m in that scene from the film Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels where a bunch of gangsters keep firing at each other by accident and one finally shouts: “Could everyone stop getting shot?” Instead of demanding that people be prevented from speaking on campus, debate them, argue back, expose the holes in their rhetoric and the flaws in their logic.

Secondly, we need to give people the tools for that fight. If you believe as I do that the free flow of ideas and opinions – as opposed to banning things – is ultimately what builds a more tolerant society, then everyone needs to be able to express themselves. One of the arguments used often in the wake of Charlie Hebdo to potentially excuse, or at least explain, what the gunmen did is that the Muslim community in France lacks a voice in mainstream media. Into this vacuum, poisonous and misrepresentative ideas that perpetuate stereotypes and exacerbate hatreds can flourish. The person with the microphone, the pen or the printing press has power over those without.

It is important not to dismiss these arguments but it is vital that the response is not to censor the speaker, the writer or the publisher. Ideas are not challenged by hiding them away and minds not changed by silence. Efforts that encourage diversity in media coverage, representation and decision-making are a good place to start.

Finally, as the reaction to the killings in Paris in November showed, solidarity makes a difference: we need to stand up to the bullies together. When Index called for republication of Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons shortly after the attacks, we wanted to show that publishers and free expression groups were united not by a political philosophy, but by an unwillingness to be cowed by bullies. Fear isolates the brave – and it makes the courageous targets for attack. We saw this clearly in the days after Charlie Hebdo when British newspapers and broadcasters shied away from publishing any of the cartoons featuring the Prophet Mohammed. We need to act together in speaking out against those who would use violence to silence us.

As we see this week, threats against freedom of expression in Europe come in all shapes and sizes. The Polish government’s plans to appoint the heads of public broadcasters has drawn complaints to the Council of Europe from journalism bodies, including Index, who argue that the changes would be “wholly unacceptable in a genuine democracy”.

In the UK, plans are afoot to curb speech in the name of protecting us from terror but which are likely to have far-reaching repercussions for all. Index, along with colleagues at English PEN, the National Secular Society and the Christian Institute will be working to ensure that doesn’t happen. This year, as every year, defending free speech will begin at home.

13 May 2014 | Asia and Pacific, News, North Korea

Gymnasts at Arirang festival in Pyongyang, North Korea (Image: Roman Kalyakin/Demotix)

Jang Jin-sung, formerly poet laureate for North Korea, is one of its highest-ranking defectors and most vocal critics. A meteoric career that saw him also become chief propagandist in the United Front Department, engaging in counter-intelligence and psychological warfare against South Korea, he was also one of Kim Jong Il’s inner circle — a dreamlike life of privilege shattered when he found the bodies of famine victims lying in the streets of his home town. Facing almost certain death for the crime of mislaying a prohibited text, he dramatically escaped to China in 2004 and defected to South Korea. Based on his insights from working in the elite, he argues that the official narrative of North Korea being run under the absolutist genius of the Kim dynasty and the Korean Workers Party, is a lie. Power was not harmoniously transferred upon Kim Il Sung’s death in 1994 to his son, Kim Jong Il — instead Kim Jong Il had long before usurped his father with the support of the clandestine Organisation and Guidance Department (OGD), while Kim Il Sung spent his last years under virtual house arrest, bamboozled by his own cult, created by his son. Kim Jong Il directed the OGD under his reign and he legitimised “every single policy and proposal, surveillance purge, execution, song and poem”, but upon his death in 2011, however, the bequest of leadership upon his son Kim Jong Un was solely symbolic; the OGD took charge. That year, Jang set up New Focus International to give insight and analysis to North Korea. This week he talked about the OGD as “the single most powerful entity in North Korea” to the All-Party Parliamentary Group on North Korea. His words were translated by NFI’s international editor, Shirley Lee, and the talk was chaired by Lord David Alton.

The OGD is “the entity that controls everything. This is where all roads end, all chains of command, and all power structures go,” Jang said. “The real power structure, nothing has changed since Kim Jong Il’s time. The OGD is still just as it is, the same men are in the same positions of power.” Yet the OGD is so secret and compartmentalised a structure, it’s only fully comprehended by the most senior leaders, and known to “less than a dozen” of the approximate 26,000 refugees out of North Korea. That lack of knowledge has meant that traditionally, outside observers omitted the OGD’s existence, basing their views on diplomatic notes, refugee testimonies and political theories which Pyongyang has successfully fed into with propaganda about the Kims’ omnipotence, to obscure its power structures. Hence, many observers interpreted the purge of Kim Jong Un’s uncle Jang Song Thaek as the new leader getting rid of his old guard to make his own power network, whereas it was really the OGD liquidating a rival. South Korea has also connived to keep a lid on knowledge of the OGD. When Hwang Jong Op, the international secretary of the Korean Workers’ Party and principal author of the state philosophy of Juche, defected and sought to tell of the OGD, the South’s then Sunshine Policy “was based on a policy of engagement that sought not to provoke the North Korean regime, [so] they actually silenced his testimony from appearing,” said Jang.

Whereupon while “every single person seen as the second, third, fourth most powerful man, has been purged or destroyed … every single powerful member of the OGD has remained”. They will stay in power as the OGD is in effect North Korea’s “human resources department, it appoints everyone”. The vetting of appointees is based on trust, and loyalty secured by cadres knowing any perception of disloyalty will imprison them, their parents and their children. “No-one is exempt from this… because no matter how big you are, if you do something wrong, you are sending your family to prison camp to rot away for the rest of their lives, never to be seen again.” As Lee put it, “you’re not going to kill your own family to change that”. Jang himself has tried many times to contact his parents in North Korea, but has never succeeded. “You can’t begin to think about what his parents may be suffering but that just makes him stronger,” said Lee.

The OGD appoints all generals and makes all military orders, with the military’s autonomy compromised like everything else by the OGD’s all-pervasive surveillance structure. Party committees of spies are installed across all sectors from diplomacy to tourism, down to each and every apartment block — “the OGD has eyes and ears everywhere”. It is backed by the OGD’s secret police and system of prison camps that the group developed into a weapon of mass terror while it usurped Kim Il Sung. He was prevented from seeing friends or family by his OGD-appointed bodyguards, a corps now numbering 100,000. He “died as a scarecrow, he was nothing,” said Lee.

As well as these physical means of control, the state seeks to monopolise all information flows and uses incredible psychological and emotional force to ensure its citizens’ loyalty. “In North Korea the only politically correct faith to have is in the cult of the Kims,” said Jang, while religious organisations like the Chosun Association or Buddhist association are run by the UFD, and Christians end up in prison camps. “The only narrative that matters is of the righteous sovereignty of the state.”

Yet for all the surface illusion of power, the nuclear weapons, the police and prison system, “it is a country that’s ruined inside, it’s a collapsed state. They do not control the price of an egg, and that is a huge deal”. Black markets have almost entirely supplanted the government monopoly of provision of goods, ranging from clothing to food, which collapsed in the mid-1990s as millions perished in the famine. This has created two classes, those loyal to the party because of their stake in the status quo; and the market class of people who were abandoned by the state and survive on the black market. Critically, this means that for promotions, status, power or material wealth, “the currency has converted from loyalty to money,” said Jang, “and that has broken the cult of North Korea for everyone”.

Economic “reforms” are really state efforts to try control the black markets, which have at times suffered violent crackdowns, for having become “a black hole that sucked in the control mechanisms of the state”. Equally, however, the regime cannot survive without them, as “the market feeds the people”. The country is also suffering from criminal activities actually sanctioned by the regime, namely counterfeit dollar bills, meth amphetamine production and computer hacking. “It’s not the world that’s suffering, the country is being destroyed by the regime’s own creations,” as government computers are hacked and fake bills and drugs run through society. Refugee statements say meth amphetamine abuse has become “just part of the ordinary life”.

Meanwhile the markets live off information. “The price of rice, the price of your life rises and falls in terms of knowing outside world information…ordinary people know it’s an advantage to listen to the outside world [information],” and Jang endorses the set up of a BBC Korea service to broadcast into North Korea. “The only way to break the dictatorship of force is by breaking that emotional monopoly over the people… There is no more effective tool that the world can do than to acknowledge that the North Korean people have the right to another narrative than that the party supplies.”

“More important is that no one in the North today believes it will last for ever,” but “the one thing that is stopping them from acting is there is no other way. Everyone is trying to do it the regime’s way”. This extends from efforts to deal with Pyongyang’s nuclear bomb program, which fail because international frameworks don’t apply to North Korea — “the only way the world can resolve the nuclear problem is seeing the regime transform. You can’t do it within their demands” — to the country’s appalling human rights record. “Those who think putting human rights on the agenda would jeopardise engagement and dialogue are wrong. North Korea is more desperate for dialogue at the state level than the West is. They [the North Korean state] need that to sustain what is happening right now.” Putting human rights atop all agendas would mean “there is nowhere left for the North Korean leadership to stand”.

“Stop looking at the regime as the agent of positive transformation,” said Jang, and engage with those with no stake in the status quo. Meanwhile, China, as the North’s sole supporter, is key to its survival and to brook any change. “China supports North Korea because it’s more convenient to support it than not,” said Jang, adding that Kim Jong Il hated China more than anybody “because he was at their mercy”, while Beijing’s anger at Jang Song Thaek’s execution was because it was “like the nightmare of Kim Jong Il would continue”. On Wednesday China warned North Korea against carrying out another nuclear test. And while China has yet to host Kim Jong Un, it has already welcomed South Korea’s President Park with open arms. Repeatedly reaffirming North Korea’s human rights record, damningly detailed by the United Nations’ Commission of Inquiry Into Human Rights in the DPRK in March, to the Chinese government may pressure them into giving up the forceful repatriation of North Korea refugees, which leads to prison or death, according to Lord Alton. “The scariest thing for China is to start to get moral blame for what’s going on in North Korea. So it will want to be seen to be doing the right thing.” On that, Jang said any retribution befalling the regime for human rights abuses, “the OGD will blame will Kim Jong Un alone”.

Again it’s an issue of perception. “In North Korea, I thought change could not come because the regime was so powerful. When I came to South Korea I learned that North Korea was not transformed because the South Koreans didn’t know it could.” Indeed, “the only thing holding North Korea back from transforming is that the world isn’t ready for it.”

The talk was organised with help from the European Alliance for Human Rights in North Korea. Jang’s book Dear Leader (UK Random House, US, Simon & Schuster) is out now.

This article was posted on May 13, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

2 Apr 2014 | Asia and Pacific, News, North Korea

A view into South Korea from North Korea (Image: Johannes Barre/iGEL/Wikimedia Commons)

North Korea hit global headlines again last week. This was in part because of the UN resolution condemning the catastrophic, ongoing abuses against its people, in the wake of a 400-page report chronicling the country’s countless human rights violations. However, as much attention, if not more, was devoted to the curious case of state-imposed hairstyles. Again it seemed the world’s focus was fixed on the bizarre end of the spectrum of outrageous stories coming out of the hermit kingdom. But while reports of haircuts, hysterical grieving masses, Dennis Rodman and killer dogs — true or not — have spread like wildfire across social media, Kim Young-Il has gone about his work of fighting for the often forgotten rights of North Korean defectors.

Kim escaped North Korea himself in 1996. Forced to join the army as a teenager, he soon discovered that the military, like the rest of the country, suffered from malnourishment. North Korea experienced devastating famine throughout the 1990s, in no small part down to mismanagement by authorities. Together with his parents, he made the gruelling journey to China, where they stayed for four-and-a-half years as illegal immigrants. “I had every job you can imagine,” he says. Finally, tired of living in constant fear of deportation, they made their way to South Korea. Kim went to university, where he says frequent questions from fellow students writing on North Korea, made him think about his heritage. After graduating he set up the non-governmental organisation PSCORE to help those who, like he did, make the difficult decision to escape.

The risks of defecting are huge. Many are put off even trying by widespread rumours backed up by state propaganda, of defectors being interrogated and killed by South Korean authorities. The country’s near complete lack of freedom of expression makes such stories difficult to debunk. Simply getting out of North Korea is no guarantee of freedom either. Many defectors have to go through China, the regime’s powerful ally, which operates a strict returns policy for defectors. Returnees face a multitude of possible punishments, from forced labour to execution. “If China changes their stance, that wholly changes the situation,” Kim says. At present, however, there is little to suggest they will. For those managing to avoid return, the threat to family left behind looms large. Kim’s sister-in-law is a political prisoner today for speaking on the phone to his wife.

Kim’s reasoning was that he’d rather face these dangers than the prospect of starving to death in his home country. It appears many agree. Nobody knows the exact number of defectors, as many keep quiet about it due to dangers posed to loved ones. What is certain is that it has shot up because of the devastating effects of the famine. This has also changed the demographic of defectors. While it used to be an option utilised mainly by relatively high-level North Koreans, today people from all sections of society are making big sacrifices in hope of a better life abroad.

Part of the reason could also be that in the some 60 years since its establishment, life in the Democratic Republic has shown no signs of improving. Kim tells of a complex and rigid class system, explaining that records of your grandparents’ position and occupation are used to determine your standing in society. The state decides who can be a doctor and who can be a farmer. Women have some possibilities for upward social mobility through marriage, but on the whole, your path in life is determined almost entirely by factors outside your control. That is, with one notable exception: “It’s difficult to move up, but very simple to drop down.”

This system, reassuring many North Koreans that there is always someone worse off than you, has played its part in deterring popular dissent and large-scale social uprising, Kim explains. That, and the crippling fear of a brutal regime acting with impunity. Asked whether any noticeable changes came with the change of leader, Kim said that any hope of the country opening up when Kim Jong-un took power following the death of his father, was quickly extinguished. The issue of South Korean pop culture is striking example. Kim Jong-un and his family are big consumers of their neighbours’ booming entertainment industry, while the official line is that it’s strictly prohibited. Kim says a man as recently found to be selling CDs with South Korean films and music. He was publicly executed to set an example for others.

So many head for China and hope. In China is where PSCORE’s work starts. Kim travels over several times a year to meet defectors and bring them to South Korea. Finding them isn’t always easy, and when he does, many are afraid to speak. “We don’t ask questions immediately. We try to identify with them first,” he explains, mindful of the rumours and propaganda they have been subjected to in the north. Many have gruelling journeys behind them. Nam Bada, PSCORE’s General Secretary, showed Index pictures of a girl’s feet, disfigured by frostbite. She lost her shoes travelling on foot in the snow. Others have used brokers; locals living in the border areas, charging to help defectors cross. The brokers are “just interested in profit, not human rights” says Kim, and estimates the price is currently between $2000-6000. The practise puts defectors, especially female ones, at risk of human trafficking. PSCORE have helped a number of women from being sold by brokers.

Once they reach South Korea, they’re interrogated by authorities. “90% of South Korea’s information about North Korea comes from defectors,” Kim explains. After that, they’re enrolled in a basic, three-month education programme, and then more or less left to their own devices. The transition from arguably the most closed society in the world, to one of the most open ones can be difficult. Kim highlight language as a big hurdle. North Korean has been completely shielded from outside influence for decades, while South Korean has been free to develop. And while there is no discrimination against defectors legally and on paper, Kim says they are often discriminated against.

It’s against this backdrop PSCORE are providing education to defectors and helping them adjust to their new lives. Kim compares the process to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: “At first, people are just glad to be fed, but later they want more.” They also continue to campaign against North Korean human rights violations, which the aforementioned UN report described as “systematic, widespread and gross” and in many instances constituting crimes against humanity. Something to keep in mind the next time North Korea is in the news because of haircuts.

Support PSCORE’s work here

This article was posted on April 2, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

11 Feb 2014 | Asia and Pacific, News, Politics and Society, South Korea

(Image: Aleksandar Mijatovic/Shutterstock)

South Korean prosecutors currently seeking a whopping 20 years imprisonment for lawmaker Lee Seok-ki on charges including praising North Korea. On 3 February, the Korean Supreme Court overturned a partial acquittal of a man charged with praising North Korea; that same day a 74-year-old man was given a sentence of two-and-a-half years for similar activities. On 28 January a man was sentenced to ten months in prison for posting pro-Pyongyang messages in an obscure online cafe.

These are some of the latest in a spate of recent cases which indicate that the South Korean government is more strictly enforcing its controversial National Security Law (NSL). Article 7 of the law long criticised as an unjust limit to freedom of expression, prescribes legal punishment for “any person who praises, incites or propagates the activities of an anti-government organisation”. What constitutes praise, incitement or propagation is not clearly defined.

While supporters say the NSL is necessary to protect a fragile peace against the North Korean threat, critics say the threat of North Korean infiltration is exaggerated and the law is really meant to stifle dissent within the country. Amnesty International said the NSL is “increasingly and arbitrarily used to curtail freedoms of association and expression”, while the United Nations special rapporteur for human rights defenders, Margaret Sekaggya, described the NSL as “seriously problematic for the exercise of freedom of expression”.

Recent years have seen cases where seemingly innocuous conduct led to criminal prosecution, notably the case of Park Jung-geun, who was indicted in 2012 on criminal charges for retweeting messages from North Korea’s official Twitter account. Between 2008 and 2011, the number of NSL cases shot up by 95.6 percent, according to an Amnesty report released in December 2012. Last year 103 people were charged with violating the law, the highest figure in ten years.

The charges against Lee Seok-ki were laid in spring of last year when Seoul and Pyongyang were engaged in a war of words that had many wondering if actual war was imminent. The main charge against him is making plans to help North Korea win in the event of a war. However, he is more likely to be convicted according to the NSL for praising North Korea at a meeting, referring to North Korea’s leadership using honorific titles. To be convicted of assisting North Korea during a war prosecutors would have to show that Lee’s plans were practicable, which is unlikely.

The NSL was instituted in the late 1940s, in the time between Korea’s colonial occupation by Japan and the start of the Korean War, ostensibly to protect South Korea from infiltration by North Korean spies. The combat phase of the Korean War ended with an armistice agreement in 1953, but no peace treaty was ever put in place, so the two countries technically remain at war. This enduring state of conflict has meant that the NSL has remained on the books as a limit to freedom of expression.

Throughout nearly all of its history, South Korea has been governed under something like a state of emergency, with the government arguing that due to the threat posed by North Korea, civil liberties needed to be suspended to maintain security and allow for economic development.

Last April, the country’s top legal authority, Justice Minister Hwang Kyo-ahn, defended use of the NSL in an interview with JTBC television. Hwang argued that pro-North Korea forces are plentiful in the South and that the NSL was needed as protection, saying: “A special kind of law is needed to defend against this special kind of crime”.

What Hwang didn’t mention is that the groups that voice these kinds of pro-North Korea statements are tiny, fringe outfits that almost no one takes seriously and have never had any real success. Critics say criminalising their statements only lends them an undue air of seriousness.

President Park Geun-hye and her cabinet are not a free speech-loving bunch, and are in office at a time of tense relations with North Korea, meaning that pro-North Korea activities are being taken seriously. Park herself is daughter of former South Korean president Park Chung-hee, a military dictator who suspended civil rights including freedom of speech in the name of national development.

The increased use of the NSL shows the durability of this logic, and the South Korean government’s steady position [means that] freedom of expression can be limited in the name of vague national objectives.

This article was posted on 12 February 2014 at indexoncensorship.org