Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Photo: Epyc Wynn/Pixanay

I think two of the most unfashionable words in the political sphere at the moment are nuance and context. As a former politician, I completely understand why controversial and provocative statements win out; why polar positions make more entertaining viewing; why pitting people at odds with each other is more likely to inspire ongoing debate and will boost the number of Twitter likes and comments.

In other words, I know why some politicians and journalists are seeking to polarise. It boosts their profile, ensures that someone, somewhere will consider them relevant and for some even ensures that they have a payday.

But the question for me at least, is what cost is this having to our public space? Where is the place for debate rather than argument? How can we build consensus and solidarity if all we’re doing is shouting abuse at each other?

Some of the most contentious debates currently occurring in democratic societies seem to have descended into virtual screaming matches. No one is listening to each other, no one is seeking to find a middle ground and seemingly few people are seeking to build bridges – our collective focus at the moment seems to be to tear each other down.

Of course, the reality is this has always been part of our political discourse. There is a healthy tradition of challenge in our public space. But… my concern is it is no longer on the fringes of our national conversations, it now dominates and the damage that it is doing is untold.

In the last week, we have seen academics compared to the KKK, a trans writer attacked for being long-listed for a literary prize for women and a new narrative on intersectional veganism which attacks other vegans for not considering the role of white supremacy in their eating habits.

I am not saying that people don’t have the right to these views – of course they do. Index on Censorship exists to ensure everyone’s rights to free expression. But that doesn’t mean that our words and deeds don’t have impact or consequence.

We witnessed in America only this year where this form of populist politics can lead to, at the extreme end – the storming of the Capitol. This week we’ve riots on the streets of Northern Ireland, again. Anti-Chinese hate crime has spiked post-Covid. In Belarus, Hungary and Poland we witness daily the appalling impact of the combination of this political polarisation and authoritarian-leaning governments. Words have consequence.

Index was launched half a century ago to provide a published space for dissidents to tell their stories and to publish their works. As we matured we provided a platform for people to debate some of the most contentious issues of the day, from the Cold War to fatwa to vaccine misinformation. We’ve done this in the spirit of providing a genuine space for free expression, a home to ensure that the hardest issues are discussed in an open, frank but measured way. That there is a space for actual debate and engagement. It is this tradition that we seek to emulate – which is why our magazine features considered commentators and thinkers tackling some of the thorniest issues of the day.

We all need a little nuance and context in our lives.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also want to read” category_id=”41669″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Attacks on press freedom in Europe are at serious risk of becoming a new normal, 14 international press freedom groups and journalists’ organisations including Index on Censorship warn today as they launch the 2020 annual report of the Council of Europe Platform to Promote the Protection of Journalism and the Safety of Journalists. The fresh assault on media freedom amid the Covid-19 pandemic has worsened an already gloomy outlook.

The report analyses alerts submitted to the platform in 2019 and shows a growing pattern of intimidation to silence journalists in Europe. The past weeks have accelerated this trend, with the pandemic producing a new wave of serious threats and attacks on press freedom in several Council of Europe member states. In response to the health crisis, governments have detained journalists for critical reporting, vastly expanded surveillance and passed new laws to punish “fake news” even as they decide themselves what is allowable and what is false without the oversight of appropriate independent bodies.

The report analyses alerts submitted to the platform in 2019 and shows a growing pattern of intimidation to silence journalists in Europe. The past weeks have accelerated this trend, with the pandemic producing a new wave of serious threats and attacks on press freedom in several Council of Europe member states. In response to the health crisis, governments have detained journalists for critical reporting, vastly expanded surveillance and passed new laws to punish “fake news” even as they decide themselves what is allowable and what is false without the oversight of appropriate independent bodies.

These threats risk a tipping point in the fight to preserve a free media in Europe. They underscore the report’s urgent wake-up call on Council of Europe member states to act quickly and resolutely to end the assault against press freedom, so that journalists and other media actors can report without fear.

Although the overall response rate by member states to the platform rose slightly to 60 % in 2019, Russia, Turkey, and Azerbaijan – three of the biggest media freedom violators – continue to ignore alerts, together with Bosnia and Herzegovina.

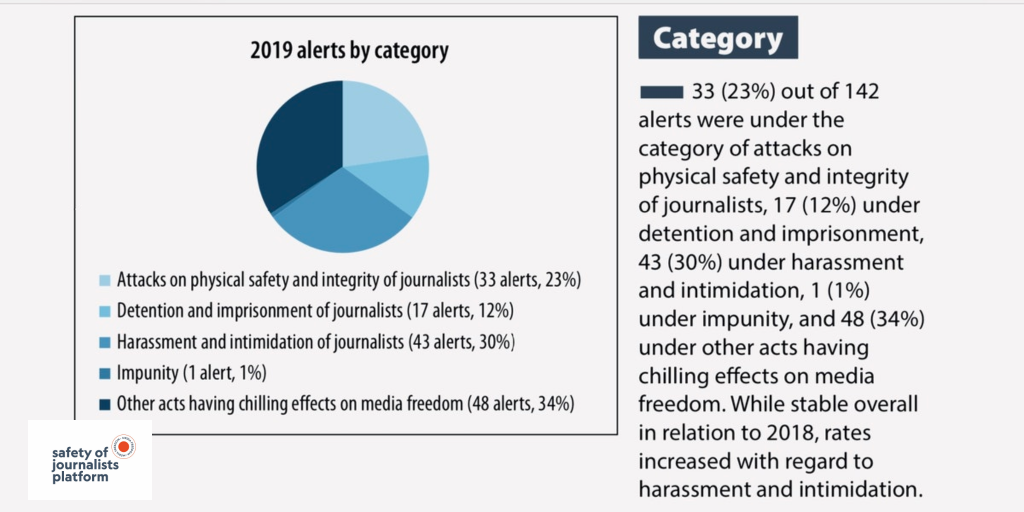

2019 was already an intense and often dangerous battleground for press freedom and freedom of expression in Europe. The platform recorded 142 serious threats to media freedom, including 33 physical attacks against journalists, 17 new cases of detention and imprisonment and 43 cases of harassment and intimidation.

The physical attacks tragically included two killings of journalists: Lyra McKee in Northern Ireland and Vadym Komarov in Ukraine. Meanwhile, the platform officially declared the murders of Daphne Caruana Galizia (2017) in Malta and Martin O’Hagan (2001) in Northern Ireland as impunity cases, highlighting authorities’ failure to bring those responsible to justice. Only Slovakia showed concrete progress in the fight against impunity, indicting the alleged mastermind and four others accused of murdering journalist Ján Kuciak and his fiancée, Martina Kušnírová.

At the end of 2019, the platform recorded 105 cases of journalists behind bars in the Council of Europe region, including 91 in Turkey alone. The situation has not improved in 2020. Despite the acute health threat, Turkey excluded journalists from a mass release of inmates in April 2020, and second-biggest jailer Azerbaijan has made new arrests over critical coverage of the country’s coronavirus response.

2019 saw a clear increase in judicial or administrative harassment against journalists, including meritless SLAPP cases, and spurious and politically motivated legal threats. Prominent examples were the false drug charges filed against Russian investigative journalist Ivan Golunov and the continued imprisonment of journalists in Ukraine’s Russia-controlled Crimea. The Covid-19 crisis has strengthened officials’ tools to harass journalists, with dangerous new “fake news” laws in countries such as Hungary and Russia that threaten journalists with jail for contravening the official line.

Other serious issues identified by 2019 alerts included expanded surveillance measures threatening journalists’ ability to protect their sources, including in France, Poland and Switzerland, as well political attempts to “capture” media through ownership and market manipulation, most conspicuously of all in Hungary. These threats, too, are exacerbated by the actions taken by several governments under the health crisis, which further include arbitrary limitations on independent reporting and on journalists’ access to official information about the pandemic.

Jessica Ní Mhainín, Index’s policy research and advocacy officer, says, “There is a growing pattern of intimidation aimed at silencing journalists in Europe. The situation in Eastern Europe – especially in Hungary, Poland, and Bulgaria – is particularly concerning. But the killing of Lyra McKee shows that we cannot take the safety of journalists for granted anywhere – not even in countries that are seen to be safe for journalists. This report provides an opportunity for us all to come to grips with the serious situation that is facing European media and to remind ourselves of the vital role that the media play in holding power to account.”

Index and the other platform partners call for urgent scrutiny of action taken by governments to claim extraordinary powers related to freedom of expression and media freedom under emergency legislation that are not strictly necessary and proportionate in response to the pandemic. Uncontrolled and unlimited state of emergency laws are open to abuse and have already had a severe chilling effect on the ability of the media to report and scrutinise the actions of state authorities.

While the platform welcomes an increased focus on press freedom by European institutions, including both the Council of Europe and European Union institutions, the ongoing crisis demands more urgent and stringent responses to protect media freedom and freedom of expression and information, and to support the financial sustainability of independent professional journalism. In the age of emergency rule, protecting the press as the watchdog of democracy cannot wait.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Martin O’Hagen (Photo: Sunday World)

An editor of the Sunday World newspaper has called for “justice to be served” as the 18th anniversary of the unsolved murder of journalist Martin O’Hagan approaches. Reporters at the Irish newspaper continue to receive regular threats from paramilitaries, he said.

Speaking to Index, Richard Sullivan, the northern editor at the Sunday World, said: “O’Hagan was dedicated to his craft as an investigative journalist and he paid the heaviest of prices for trying to make his homeland a better place”. He expressed frustration that the investigation into O’Hagan’s murder has come to nothing; prosecutors dropped the case in January 2013 citing a risk of basing it on unsubstantiated evidence.

“We are in despair that those responsible for Martin’s death remain at large, but we will continue to keep his case in the public eye in the hope that one day justice will be served,” Sullivan said.

Meanwhile, staff at the Sunday World, the second largest selling newspaper in the Republic of Ireland and also on sale in Northern Ireland, continue to work under considerable pressure from paramilitary organisations. “It’s been 18 years since he was shot and killed; in that time Sunday World journalists continue to work under constant threat. As recently as January this year a journalist on this newspaper was given 48 hours to get out of the country or be killed. It is a sad indictment that in 2019 journalists working in a major UK city continue to have their lives placed under threat,” said Sullivan.

On 26 August 2019, the European/International Federation of Journalists and Index on Censorship filed an alert with the Council of Europe regarding the continued impunity for O’Hagan’s murder. The platform’s 2019 annual report, warned that “a climate of impunity has started to take hold in parts of Europe” and called for “the swift completion of a transparent and effective investigations and prosecutions leading to the punishment of all those found responsible.”

Eighteen years ago this month, O’Hagan was murdered in Lurgan, Northern Ireland. He was shot several times from a passing car while walking home from a pub with his wife on 28 September 2001. Although the Red Hand Defenders – a nom de guerre used by the Loyalist Volunteer Force – claimed responsibility for his murder, his killers have never been brought to justice. Until Lyra McKee’s death earlier this year, O’Hagan had been the only journalist to be killed in Northern Ireland.

O’Hagan was an investigative reporter with the Sunday World newspaper, specialising in stories about drug gangs and paramilitaries. He had repeatedly been threatened by both republican and loyalist paramilitaries as a result of his work. He had previously served five years in jail for gun running for the IRA.

In 1989, the Provisional IRA “invited” him to interview them, but instead abducted him and threatened him with torture and death. He was released with a warning after successfully convincing them that he had not worked as a police informer. After O’Hagan exposed LVF member Billy Wright as a sectarian assassin in 1992, Wright threatened O’Hagan and attempted to have him killed. O’Hagan left Northern Ireland on advice from the police, and only returned after the paramilitary ceasefires in 1995.

Paramilitary organisations have long targeted staff at the Sunday World. In 1984, one former journalist from the paper was seriously wounded when he was shot by the Ulster Volunteer Force. Another has repeatedly said he could have “wallpapered a room” with the 21 death threats that were passed on to him by police. In October 1992, two gunmen held staff at gunpoint before planting a bomb in the office doorway – journalists were forced to jump over the bomb as they fled. And in January 1999, the outlet’s Belfast offices were badly damaged in an arson attack.

Last year on the 17th anniversary of O’Hagan’s killing, the National Union of Journalists renewed their call on the Irish and British governments to commission an independent investigation into his murder. “Martin’s murder was a matter of international concern and the failure of the police to apprehend those who killed him is still of concern to all who care about human rights and the right of journalists to operate freely and without threat,” said NUJ Secretary, Séamus Dooley.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1567701911745-37eade37-ad90-4″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Update: Update: On 3 June 2019, the criminal investigation into Trevor Birney and Barry McCaffrey was dropped. The Durham Constabulary and the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) announced that they were no longer investigating the two journalists.

Update: On 31 May the High Court in Belfast ruled that journalists Trevor Birney and Barry McCaffrey acted lawfully, that police warrants against them were “inappropriate” and that all confiscated material be returned. Justice Morgan said that the material “does not indicate that the journalists acted in anything other than a perfectly proper manner”. “We consider that there’s no reason why, subject to suitable protections, for declining to return the material in their entirety to the journalists,” he added.

Index on Censorship and English PEN welcome the decision by the High Court in Northern Ireland to quash the warrants obtained by police to carry out raids on the homes and office of Belfast journalists Trevor Birney and Barry McCaffrey.

Birney and McCaffrey produced a documentary No Stone Unturned which examines claims of state collusion in the murders of six men.

In evidence submitted to the High Court in Northern Ireland, Index on Censorship and English PEN said the raid on the homes and office of Birney and McCaffrey should be ruled unlawful.

Index on Censorship and English PEN filed a written submission to the court on May 17 after the court granted permission for the organisations to intervene. Index on Censorship and English PEN are represented by solicitor Darragh Mackin at Phoenix Law and barrister Jude Bunting at Doughty Street Chambers.

Lord Chief Justice of Northern Ireland Sir Declan Morgan said: “We are minded to quash the warrants on the basis that they were inappropriate, whatever the other arguments.”

A further hearing is set for 2pm on Friday 31 May which will determine what remedy to grant following the success of the judicial review. The remedies could include: quashing the warrant; ordering the return to the journalists of the documents seized by police; damages.

Index on Censorship magazine editor Rachael Jolley said: “We welcome the news that the Lord Chief Justice is minded to quash the warrants against Trevor Birney and Barry McCaffrey. This is a significant step to ensure that press freedom is protected. English PEN and Index argued in a submission to the court that the conduct carried out in this case to raid the journalists’ houses and carry away documents and items that were not even related to the documentary was likely to have the effect of intimidating journalists throughout Northern Ireland and further afield.”

English PEN Director Antonia Byatt said: “We are very encouraged by this latest development in the case against Northern Irish journalists Trevor Birney and Barry McCaffrey, following our joint intervention in the case against them last week. We hope very much that Friday’s hearing will bring more good news. It is crucial that freedom of the press in the UK is protected, especially in the light of Jeremy Hunt’s current campaign for global media freedom.”

Mackin of Phoenix Law, said: “This is a victory for press freedom and common sense. The protection of journalistic material and sources is one of the basic conditions for freedom of expression. If journalists and their sources cannot rely on confidentiality, they may decide not to exchange information on sensitive matters of public interest for fear of the consequences. As a result, the vital “public watchdog” role of the press will be undermined and the ability of the press to provide accurate and reliable reporting may be adversely affected. This is why the approach of the police in this case was so obviously wrong. The decision to grant a warrant to obtain information from journalists, without giving them an opportunity to comment, had the purpose or effect of intimidating journalists the world over. The international significance of this claim is reflected in our client’s intervention.”

Index on Censorship is a London-based non-profit organisation that publishes work by censored writers and artists and campaigns against censorship worldwide. Since its founding in 1972, Index on Censorship has published some of the greatest names in literature in its award-winning quarterly magazine, including Samuel Beckett, Nadine Gordimer, Mario Vargas Llosa, Arthur Miller and Kurt Vonnegut. It also has published some of the world’s best campaigning writers from Vaclav Havel to Elif Shafak. Contact: [email protected].

English PEN is a registered charity and membership organisation which campaigns in the United Kingdom and around the world to protect the freedom to share information and ideas through writing.PEN supports authors and journalists in the United Kingdom and internationally who are prosecuted, persecuted, detained, or imprisoned for exercising the right to freedom of expression. English PEN has a strong record of campaigning for legal reform throughout the United Kingdom.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1559659124565-535dd29e-e875-4″ taxonomies=”8996″][/vc_column][/vc_row]