20 Jun 2017 | Campaigns -- Featured, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]We, the undersigned, journalists’ and freedom of expression organisations, are writing to urge the Permanent Council of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe to appoint a new mandate holder to the Office of OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media (RFoM) following the end of Ms Dunja Mijatović’s tenure in the position in March of this year.

As we stated in our letter dated 16 February 2017, we believe strongly in the high value and importance of the Office of the RFoM, and in the mandate of the Representative that has been agreed by all OSCE participating states:

“The OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media has an early warning function and provides rapid response to serious non-compliance with regard to free media and freedom of expression. The OSCE participating States consider freedom of expression a fundamental and internationally recognised human right and a basic component of a democratic society. Free media is essential to a free and open society and accountable governments. The Representative is mandated to observe media developments in the participating States and to advocate and promote full compliance with the Organisation’s principles and commitments in respect of freedom of expression and free media.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-times” color=”black” background_style=”rounded” size=”xl” align=”right”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

The work of the RFoM remains of critical importance, with journalists and media workers facing significant and new pressures across the OSCE region

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Since its inception in 1998, the Office has had a mandate holder without interruption, and successive Representatives on Freedom of the Media have helped to maintain freedom of media on the policy agenda within the OSCE and made a considerable contribution to a number of initiatives related to press freedom in the OSCE region. This was made possible by both the independence conferred on the Office and the profile of the Representatives who have shown determination, vision and steadfastness in fulfilling their mandate.

The former mandate holder, Ms Dunja Mijatović, left the Office on 10 March 2017, having served a one-year extension of her two three-year terms. The Austrian Chairmanship of the OSCE gave a deadline of 7 April 2017 for nominations for her replacement and yet, to date, there has been no announcement of her successor.

This situation is of great concern to media and other stakeholders, including many organisations actively concerned for media freedom in Europe who fear losing a valuable partner and voice. The work of the RFoM remains of critical importance, with journalists and media workers facing significant and new pressures across the OSCE region.

While the Office of the Representative has continued to uphold its mandate in the transition period since Ms Mijatović’s departure, the strong leadership of the Representative is essential to ensure national governments across the region remain accountable to their commitments to the protection of journalists and media independence. A failure to appoint a new mandate holder risks rolling back progress achieved in protecting media freedoms, undermining advances into promoting stable, tolerant and accountable societies.

That is why we urge all Participating States to press on the OSCE the need to appoint a new Representative on Freedom of the Media without delay and to ensure the Office’s achievements over the last two decades are not lost.

We also encourage the Participating States to use their collective weight to influence the choice of the new Representative, and by doing so, ensure the best profile possible with a track record of independence and proved commitment to freedom of expression and freedom of the press for this important position.

19 June 2017

Association of European Journalists (AEJ)

Article 19

Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ)

European Federation of Journalists (EFJ)

International Federation of Journalists (IFJ)

Index on Censorship

International Press Institute (IPI)

Reporters Sans Frontières (RSF)

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1497967874947-321034c0-bb1f-2″ taxonomies=”8996″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content_no_spaces” content_placement=”middle”][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”91122″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/05/stand-up-for-satire/”][/vc_column][/vc_row]

16 Feb 2017 | Campaigns, Campaigns -- Featured, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]We, the undersigned, major journalists’ and freedom of expression organisations, are writing to urge the Permanent Council of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe to ensure continuity of the Office of OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media at the end of Ms Dunja Mijatović’s tenure.

We believe strongly in the high value and importance of the Office of the Representative on Freedom of the Media, and in the mandate for the Representative that has been agreed by all OSCE participating states:

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”black” background_style=”rounded” size=”lg” align=”right”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

The OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media has an early warning function and provides rapid response to serious non-compliance with regard to free media and freedom of expression. The OSCE participating States consider freedom of expression a fundamental and internationally recognized human right and a basic component of a democratic society. Free media is essential to a free and open society and accountable governments. The Representative is mandated to observe media developments in the participating States and to advocate and promote full compliance with the Organization’s principles and commitments in respect of freedom of expression and free media.”

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]Since its inception in 1998, the Office has had a mandate holder without interruption, and successive Representatives on Freedom of the Media have helped to maintain freedom of media on the policy agenda within the OSCE and made a considerable contribution to a number of initiatives related to press freedom in the OSCE region. This was made possible by both the independence conferred on the Office and the profile of the Representatives who have shown determination, vision and steadfastness in fulfilling their mandate.

We understand that the current mandate holder, Ms Dunja Mijatović, is due to leave Office in a month’s time after serving a one year extension of her two three-year terms. And yet, to date, there has been no announcement of her successor just weeks before the position becomes vacant.

This situation is of great concern to media and other stakeholders, including many organisations actively concerned for media freedom in Europe who fear losing a valuable partner and voice. The work of the Representative on Freedom of the Media is more important than ever before, with journalists facing unprecedented pressures on the continent and across the OSCE area as a whole.

We wish therefore to warn against the risk of rolling back the progress achieved in protecting media freedoms, undermining advances into promoting stable, tolerant and accountable societies.

That is why we urge all Participating States to press on the OSCE the need to appoint a new Representative on Freedom of the Media without delay and to ensure the Office’s achievements over the last two decades are not lost.

We also encourage the Participating States to use their collective weight to influence the choice of the new Representative, and by doing so, ensure the best profile possible with a track record of independence and proved commitment to freedom of expression and freedom of the press for this important position.

Brussels, 16 February, 2017

Association of European Journalists (AEJ)

Article 19

Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ)

European Federation of Journalists (EFJ)

International Federation of Journalists (IFJ)

Index on Censorship

International Press Institute (IPI)

Reporters Sans Frontières (RSF)[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1487242081444-87bd062c-eeaa-0″ taxonomies=”6380″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

20 Jan 2017 | Media Freedom, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]In recent years, there has been a perceptible increase in far-reaching restrictions on the media across the globe. This impulse to restrain media freedom stems from a variety of real and perceived “threats” – from concerns about national security, to demands for media “ethics” and “responsibility”, to accusations of the media’s role in the dissemination of so-called “fake news”, most recently. The urge of states to regulate is also reinforced by the overall devaluation of the critical role played by a free and independent media across liberal democracies around the world.

The trend towards ramping up the regulation of the media has worrying implications in these states and others who are currently considering a similar response: the inability of the media to perform its role as a – if not, the – key public watchdog, the erosion of states’ international legal obligations and political commitments on freedom of expression, and a lessening of freedom of the media as a whole.

Under international law, specifically Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, states do not have free reign to control the media. Limitations on media freedom, as an aspect of freedom of expression, are allowed only in certain, narrowly defined circumstances, such as national security or the protection of privacy. However, a great many governments are currently approaching media regulation as though restrictions may be imposed at the complete discretion of states regardless of international law and commitments.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner content_placement=”top”][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”black” size=”lg” align=”right”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

The trend towards ramping up the regulation of the media has worrying implications

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]There have been moves to exert political control over how the media is regulated in a number of OSCE participating states. Take, for example, the January 2016 decision by Poland in a move reminiscent of Hungary’s media law reforms of 2012, to enact a law handing over the power to appoint and dismiss members of management boards of public service broadcasters, Polski Radio and Telewizja Polska, from the National Broadcasting Council to the government. I warned, before the adoption, that the legislation “endanger[s] the basic conditions of independence, objectivity and impartiality of public service broadcasters”.

Anxieties about the effects of media regulation on media freedom are not limited to transitional or newer democracies, however, as the recent debate around the implementation of section 40 of the Crime and Courts Act 2013 in the UK, a traditional bastion of press freedom, suggests. As I have noted, the commencement of the provision would have punitive effects on the press for reporting on public interest issues in the UK, and have an especially onerous impact up on local and regional newspapers who are already facing significant financial challenges. It would also mean that the UK as a long-standing bastion of press freedom would send out a negative message to other states on the possibilities to regulation.

The picture is not all bad, of course. Some states have made significant positive strides in advancing freedom of the media by engaging with my office on legislative amendments, such as the government of the Netherlands on its draft Law on the Intelligence and Security Services, while others have shown advances in terms of case-law, such as Norway on the protection of sources.

Unfortunately, however, the dominant trend is a regressive one – towards control of the media rather than the reinforcement of it through, among other things, the promotion of media self-regulation and pluralism. This tendency of states to try and control the media is not just a matter of concern for my office, other international institutions, the media itself and civil society organisations. It is one that should worry all those who care about democratic values, the rule of law and human rights.

Dunja Mijatović is the Representative on Freedom of the Media for the OSCE, based in Vienna.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1484907257319-fb6254e3-0fad-6″ taxonomies=”6380″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

1 Dec 2016 | European Union, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

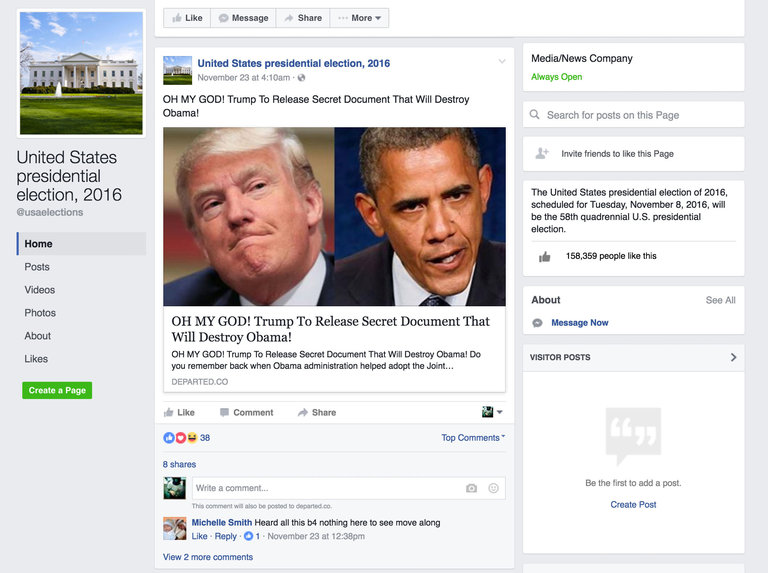

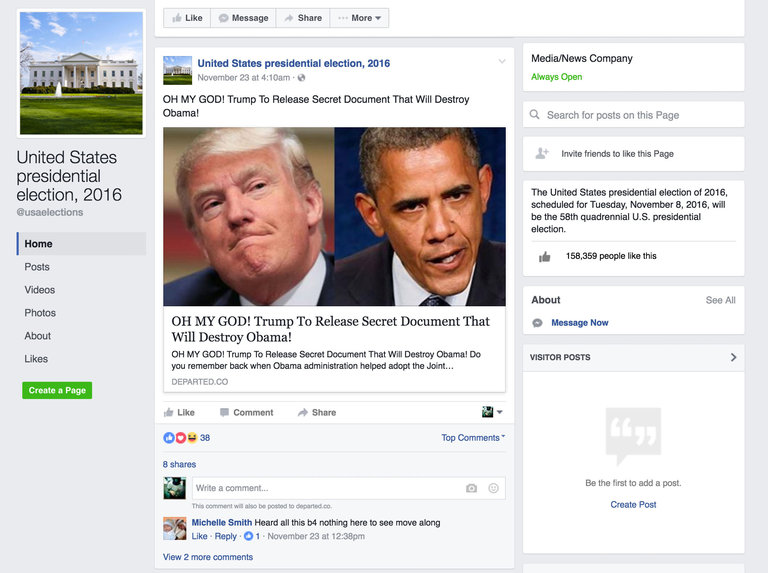

Social media is all atwitter these days with the unremarkable discovery that people lie.

So much so that Oxford Dictionaries has designated “post-truth” as its international word of the year. For those of you not hip to the jargon, it means “relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief.”

In other words, facts don’t count.

Perhaps spawned by the spate of alleged news stories made up out of whole cloth during the recent presidential election in the United States, people of all stripes are weighing in on the issue du jour: How can we ensure that what we read on Facebook or Twitter is real?

I ask, “Why bother?”

Consider the Ninth Commandment (or Eighth, at least as interpreted by Catholics and Lutherans): “Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbour.”

That sounds like a dire warning against lying, which was something that must have been quite popular during the day, and still is. Besides going to hell, most every country in the world has libel laws designed to compensate people whose reputations have been damaged by lies.

But today the allegation of lying seems to be taking on more sinister effects. There have been some allegations that false news stories actually swung votes in the US presidential election. If so, why is “fake news” so effective? I believe we can go back to Lord Mansfield’s 18th century dictum “the greater the truth, the greater the libel” for some insight. Whether we just want to believe something is true or we pick and choose our truths to match our political cloth, we find ourselves in an era where we can scan a headline, read the lede and say, “That seems believable enough.”

Thus, manufacturing stories out of thin air has become a cottage industry and an apparently successful one.

Trying to get on the perceived “right side” of the issue, it comes as little surprise that social media companies such as Facebook are engaged in damage control, saying they are trying out new versions of their algorithms to weed out postings that are simply made up.

And to that I again ask, “Why bother?”

For in fact, doing so may just cause greater harm to free expression than any lie, no matter how damaging.

Because besides the difficulty in determining truth from opinion to a bald-faced lie, the inherent limiting of ideas, including criminalising them, makes us all suffer a little bit.

Today we are seeing criminal and administrative prosecution for activities on social media platforms that involve responding to existing content (i.e. sharing, re-posting, uploading, liking, quoting and commenting) and that contributes to an environment of fear.

Combine this with the growing tendency for nations to apply anti-extremism and anti-terrorism laws to content on social media platforms and the result is social media users, including members of the media, are being fined, arrested and imprisoned for interacting or reacting to content produced by third parties or for expressing their opinions on it.

This is censorship and can lead to self-censorship.

Instead, issues related to social media activities should be addressed exclusively through self-regulation, education and literacy, not through new restrictions.

As the Representative on Freedom of the Media for the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, I recently recommended that the participating states that comprise the body to recognize the following:

- That no one should be penalised for social media activities that come as a reaction or interaction with existing content;

- That no one should be penalised for the social media activities such as posting and direct messaging unless they can be directly connected to violent actions and satisfy the test of an “imminent lawless action”;

- That no one should be held liable for content on social media platforms and on the internet of which they are not the author, as long as they do not specifically intervene in that content or refuse to comply with court orders to remove that content, where that have the capacity to do so (“mere conduit principle”);

- The necessity to decriminalise defamation, insult and blasphemy;

- That any imposition of any sanctions imposed by courts of law, especially when it comes to social media activities, should be in strict conformity with the principle of proportionality;

- The need for education and literacy on freedom of expression on the internet.

Let’s not overreact to the wave of fake news by building another wall around the internet.

Dunja Mijatović is the Representative on Freedom of the Media for the OSCE, based in Vienna.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1480348630223-46408dc4-0b68-7″ taxonomies=”6380″][/vc_column][/vc_row]