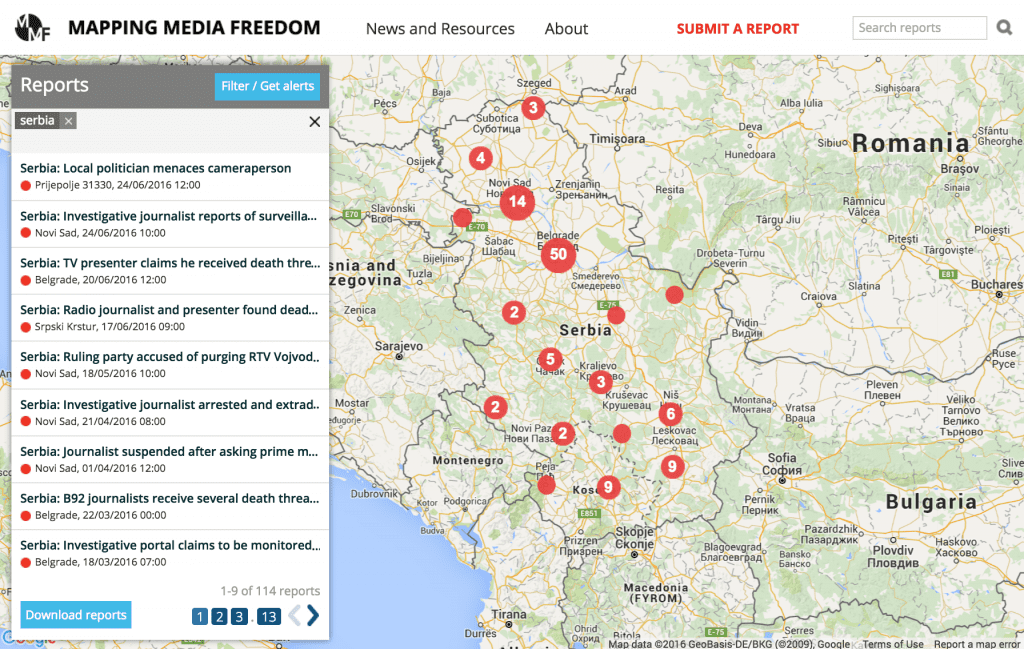

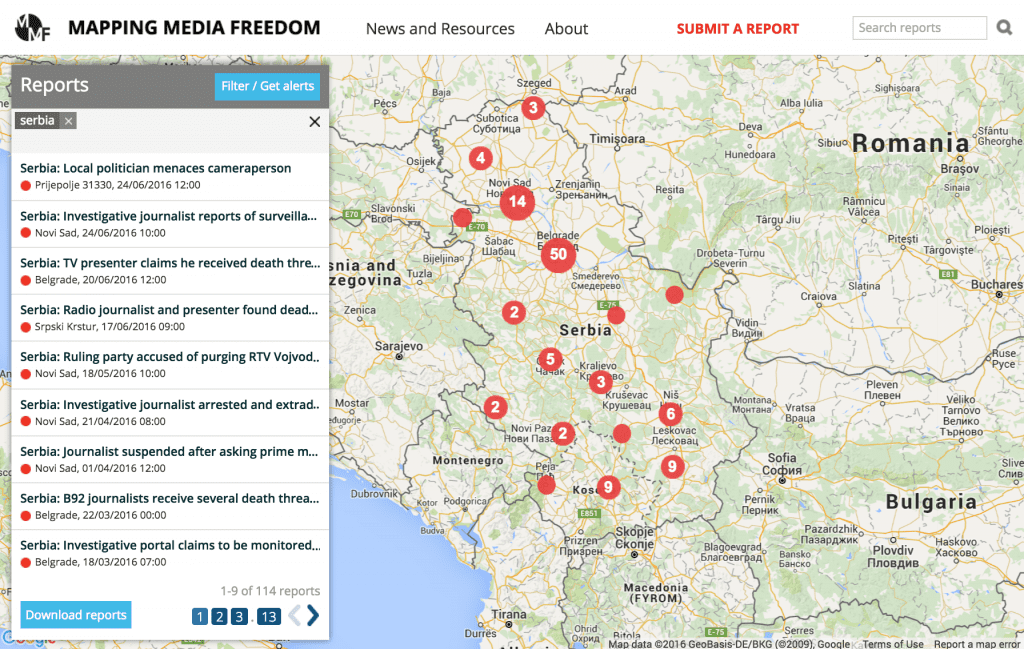

6 Jul 2016 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News, Serbia

Journalists and citizens in Serbia’s northern city of Novi Sad are taking the streets after a wave of dismissals at the regional broadcaster Radio Television Vojvodina, which they believe is a direct result of political pressure.

It was late in the afternoon on 17 May when journalist Vanja Djuric heard that her job was no longer necessary. “We had just prepared the news items for the next day,” she told Index on Censorship. “They just told us, ‘You don’t have to come to work tomorrow.’”

She was not the only one. By the end of that week, 18 RTV employers had been replaced without explanation. Some received a phone call, others were stopped in the building’s hallway. “The whole newsroom, all the editors and journalists, we’d all been sent home,” Djuric added.

Novi Sad, Serbia’s second city, has been the centre of protests for media freedom ever since. Thousands have taken the streets to demonstrate against editorial reforms at one of the biggest public broadcaster in the country. Protesters believe that the ruling party of Prime Minister Aleksandar Vucic is gradually taking control over the radio and tv station that used to be one of the few independent broadcasting media companies in Serbia.

It is believed that the dismissals of RTV editorial staff was a direct result of a shift in government in the autonomous province of Vojvodina.

Elections had taken place on 24 April and the results, which caused a dramatic shift in power when the results were revealed on 4 May. The Serbian Progressive Party had won a majority like it already had on a national level.

The national equivalent of RTV, Radio Television Serbia, is already under strict government control, and major concerns have been raised that RTV is now headed into the same direction.

Over 100 journalists and editors have signed an open letter criticising the dismissals and asking the new board of directors to resign and to restore free media at RTV. A newly formed protest movement called Podrzi RTV (Support RTV) has organised four protests so far.

Vojvodina’s journalist association, the Independent Journalist Association of Vojvodina, believes that the new political leaders were intended to take over the public broadcaster. “The political takeover of one of the most objective televisions in Serbia started immediately after the elections with the non-transparent replacement of RTV’s programme director,” Nedim Sejdinovic, president of the Independent Journalist Association of Vojvodina told Index on Censorship.

“Soon after that the general director and the director of one of the most popular news programmes resigned,” he said. “It was the start of the new leadership.”

Most journalists were taken off their editorial positions and transferred to non-journalistic jobs within RTV. The programme schedule changed overnight. “Under the excuse of ‘summer shifts’, they took down almost every political and investigative programme,” Sejdinovic said.

While the majority of the journalists are still on the payroll, five prominent journalists so far have been fired.

NDNV is expecting more journalists to lose their jobs in the coming months. The association is looking into the dismissals with a team of lawyers. “We found out that most dismissals were against the law so we are preparing court cases up to the European Court for Human Rights,” said Sejdinovic. Serbia’s national journalist associations NUNS and UNS, as well as the OSCE have strongly condemned the developments at RTV.

Journalist Sanja Kljajic was working on RTV’s recently launched investigative journalism programme, which was also cancelled by the new management. She is one of the initiators of the protest movement Podrzi RTV.

“We’ve been accused that we were not objective and didn’t fulfil our role as a public service, with no evidence or arguments,” she told Index on Censorship. Her show was called Behind the Wall, the first season was about to start, dealing with the country’s problems within the judicial system. “Bearing in mind that we were doing research about terrible results of the judicial reforms over the past 15 years in Serbia, we are sure that the reason for cancelling the project is a textbook example of censorship,” said Kljajic.

RTV had a unique reputation in Serbia, where the media has become more and more unfree in the recent years. It had managed to operate objectively and has been praised for being one of the few broadcasters in the country that managed to resist political pressure. While other public media have turned into a mouthpiece for the prime minister, RTV kept broadcasting debates and critical reports. Sanja Kljajic was proud to be a part of it. “I was free to ask any question to anyone,” she said.

That started to change already in the period leading up to the elections. There were signs that control was about to get tightened. At the beginning of April, journalist Svetlana Bozic-Kraincanic was expelled and had her salary cut after asking the prime minister, Aleksandar Vucic, a critical question during a press conference. It was election time, Vucic was running to be re-elected. Bozic-Kraincanic touched on a sensitive topic asking him about his ties with the Serbian Radical Party of the recently acquitted war criminal Vojislav Seselj, a party of which Vucic was a member during the 1990s war in former Yugoslavia.

“It is very disturbing that RTV is now transformed into another media that serves the regime of prime minister Aleksandar Vucic,” said Nedim Sejdinovic of NDNV. However, he also sees optimism in the response it has got. “The protests have brought out to the streets of Novi Sad not just journalists, but also citizens themselves,” he added. “The story of journalists became the story of the people. They are coming to the protest to show their growing dissatisfaction with the current government.”

An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated the date of the elections.

6 Jun 2016 | Croatia, Europe and Central Asia, European Union, Hungary, News

Since the 1920s, generations of western Europeans got used to the monopoly of public radio and later public television. These broadcasters developed strategies to better serve audiences and distance themselves from governments. The arrival of private broadcasters, in many cases taking place only in the 1970’s, was generally viewed as a complimentary service aimed at entertaining the public. Although public service broadcasting lost market share, it remained a respected institution in society; necessary to bring up youth, to get an objective picture of the world and cater to the interests of minorities.

Eastern Europeans also got used to the monopoly of state radio and television. Those broadcasters served the communist parties and were administered and financed by governments. Their political bankruptcy came with the collapse of communist ideology, underlined in particular by the plurality of private broadcasters that came on to the scene in the early 1990s.

These private media – with plentiful Western programming – was indeed television, for so long hidden from the viewers by totalitarian regimes. Politicians flocked to their studios to take part in talk shows, abandoning once-mighty state television. Thus, in the east, the public perception of public broadcasting was predominantly sceptical, if not negative. A discussion on its development was of tangential interest, at least during the saturation process of the new private media.

Abandoned by politicians and the public, the slow and clumsy transformation of the state broadcasters into public ones was guided by the bureaucrats, almost by themselves. The driving force behind the transformation was almost exclusively the activity of Strasbourg and Brussels. We all know that in the words of European institutions “public service broadcasting is a vital element of democracy in Europe.” Transformation of state television into a public one was a condition precedent of new democracies becoming member states of the Council of Europe in some cases. The authenticity of the transformation has been important to become a candidate for entry into the European Union and even sometimes to NATO.

Developments in younger EU member states show the importance of public service broadcasters for the development of democracy – and how they can be misused.

In December 2015, Poland‘s parliament adopted a law giving the treasury minister the mandate to appoint and dismiss members of management and supervisory boards. Since the law came into effect in January, reportedly more than 100 journalists in public media have lost their jobs, allegedly for not being government-friendly.

In March, the Croatian parliament dismissed the director general of Croatian Radio-Television. A week later, the government also proposed that parliament reject a regular report from the independent media regulator, both events raising serious concerns about the overall media freedom situation in the country.

Hungary was probably the first example in the EU where public service broadcasting was practically turned back into state broadcasting, going against international standards calling for independence. New media laws in 2010 and the restructuring of the media landscape led, within a matter of one year, to all public service media being subordinated to political decisions. The new system introduced and cemented the political dependence of public service media; the governing party had nominated all new heads of public service media and the Media Authority now controls the budget of all public service media. The law vested unusually broad powers in the politically homogeneous Media Authority and Media Council, enabling them to control content of all media.

The battle to establish credible public service broadcasters in transitional democracies has been even more difficult to wage.

The latest example is the steering board of Bosnian Radio and Television which last month decided to suspend operation of all programming at the end of this month. This decision, a wrong one for several reasons, follows years of political and financial wrangling over control of the operation.

Throughout the western Balkans, significant issues are pending affecting the independence and financial stability of public broadcasting.

A bureaucratic response to the need to establish public service broadcasters has brought predictable results. The newly established broadcasters were visibly underfunded, with formal and informal administrative links – if not strings – to governments and no clear commitments to the public. Once established, it was unclear what to do with them. Most governments viewed them as an element of bureaucracy itself, a burden to carry on the road to a united Europe. If possible and convenient, they tried to make use of them through a carrot-and-stick policy.

As such, the new public service broadcasters immediately became subject to criticism by almost anyone who wanted to speak about them. Left to survive in the monstrous buildings of brutal architecture that once belonged to powerful state television, they had to sell airtime to advertisers, beg for Western donations and save on everything.

The advance of the internet and other new technologies almost killed the whole idea of television and radio, including public service broadcasting. It was saved by the transformation process – from public service broadcasting to public service media. In the West, the BBC and other companies have struggled to make use of the changing trends in media consumption. They went online, launched smartphone applications, became interactive, archived in order to engage fragmented audiences where and when required by the viewers.

Unfortunately this is not the case in the East. Public service broadcasters at best try to appeal to the older and well-educated audiences, traditional in their use of public service media. For our children, today’s debate is not only irrelevant, it is beyond their understanding.

Is there a future?

In my view we are losing the battle and might soon lose the war. To reverse the trend, we should do the following:

Give public service broadcasters a clear-cut mandate and obligation to program for the public which, in turn, should have effective feedback and control over content. There should be programmes that cater to minorities; there should be objective news, calm and matter-of-fact debates, educational and children’s programmes.

Public service broadcasters should function independently of the government. Buffer boards, meaning councils should be established to guarantee that only an abuse of a clear-cut mandate may serve to reprimand or dismiss an editor; only mismanagement and corruption may lead to firing executive directors.

And, finally, licence fees should be introduced or increased to heighten a feeling of public ownership. We can talk about other methods of independent funding, but none of them may bring this feeling of owning an institution that serves you.

Recent columns:

Dunja Mijatović: Chronicling infringements on internet freedom is a necessary task

Dunja Mijatović: Propaganda is ugly scar on face of modern journalism

Dunja Mijatović: There is hope that justice can be served in Serbia

22 Dec 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News, Russia, Turkey

Before 24 November, Turkey was described in Russian news reports as a reliable partner in ambitious projects (TurkStream pipeline, construction of Sochi’s Olympic venues), a source of fruits and vegetables in a period of European food embargoes and Crimea blockade, and one of the main tourist destinations, visited annually by over three million Russians.

But after the downing of the Russian fighter jet, Turkey became the target of a new information war. Reports on estimated growth of turnover and perks at Turkish resorts in Russian state-run media were replaced by a long list of accusations.

Dmitry Kiselev, the head of a state international news agency Rossiya Segodnya and the anchorperson of a weekly programme Vesti Nedeli accused Turkey of buying oil from the Islamic State, exporting carcinogenic vegetables to Russia and trying to revive the Ottoman Empire. Vladimir Soloviev, a popular anchorperson on television channel Rossiya 1, labeled Turkey a sponsor of terrorism.

All media platforms, directly or indirectly controlled by the state, were used in the construction of an image of a new enemy. The past was revised by articles, recalling a long history of Russian-Turkish wars and crimes of the Ottoman Empire. The future was programmed by analysing chances in a possible third world war. Coverage of current affairs has become far from unbiased. News selection has been focused on demonstration of Russia’s sanctions effects and Turkey’s internal problems — oppression of journalists, a growth of child marriage and crime.

After weeks under information attack, on 3 December, Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu dismissed the allegations by Russian media as “lies of this Soviet-style propaganda machine”.

“In the Cold War period, there was a Soviet propaganda machine. Every day it created different lies. Firstly, they would believe them and then expect the world to believe them. These were remembered as Pravda lies and nonsense,” he said.

Days later the Russian state news agency RIA Novosti proved his point by using a classic Soviet propaganda trick. In an op-ed that called Davutoglu “Reich Minister”, RIA Novosti compared the new enemy to the old by appealing to one of the most loathed images for all Russian people since the WWII – Nazi Germany.

This method, as with many others used against Turkey, has been tested and mastered during the Ukrainian crisis. Maidan activists, who later became a new elite of the country, were also labeled by Russian television channels as “fascist nationalists” and “extremists”. The technology of information war, the main propaganda mouthpieces and the image of the enemy remain the same.

On 7 December, Russian Public Opinion Research Center (VTsIOM) published the results of its survey, saying that 73% of Russian population have changed their attitude to Turkey to the worse since the downing of Su-24.

VTsiom, whose director admitted that the main clients of the center are the Kremlin and the ruling party United Russia, has been criticised for manipulation. The results of the survey are symptomatic. If the data is correct, it demonstrates that anti-Turkey propaganda works very well. If the results were rigged in favour of the Kremlin’s agenda, it shows the desirable goal of the information attack.

The day after, on 8 December, a film crew from Russia’s state television channel Rossiya 1 was detained in the Turkish province of Hatay, close to the Syrian border, and deported from the country because of “violations of regulations of work of foreign journalists in the Turkish Republic”. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation responded with harsh critiques, accusing Turkey of “a series of infringements of the rights of local and foreign journalists”.

However, in a communique by OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media on propaganda in times of conflicts, published last year in reference to a similar case related to the Ukrainian crisis, Dunja Mijatović made it clear that censoring propaganda is not the way to counter it. The best way to neutralise propaganda is balance and accuracy in broadcasting, independence of media regulators, prominence of public service broadcasting with a special mission to include all viewpoints, a clear distinction between fact and opinion in journalism and transparency of media ownership.

A similar view was expressed in a speech by Agnès Callamard, the former executive director of ARTICLE 19, delivered at UN Headquarters in December 2014.

“Hatred needs and is fed by censorship, which, in turn, is needed to nurture incitement to the actual commission of atrocity crimes. The lesson is clear: In our efforts to prevent mass atrocities, the free flow of information and freedom of expression are ultimately are our key allies – not our enemies.”

3 Dec 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News

Propaganda, counterpropaganda and information wars are all terms that, unfortunately, have become part of our daily discourse.

Propaganda, counterpropaganda and information wars are all terms that, unfortunately, have become part of our daily discourse.

As the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) Representative on Freedom of the Media, I have raised the issue of propaganda emanating from the conflict in and around Ukraine. I have called propaganda an ugly scar on the face of modern journalism and called on governments to get out of the news business.

Tackling propaganda is not a new concept to the participating states of the OSCE. It goes back to the beginning of this organization. At the time of the Helsinki Final Act, the participating states committed themselves to promote “a climate of confidence and respect among peoples consonant with their duty to refrain from propaganda for wars of aggression” against other participating states.

Those promises were broken for the first time before and during the war in former Yugoslavia in the 1990s. Dangerous stereotypes that dominated state media since the beginning of the crisis significantly contributed to the development of an intolerant atmosphere and influenced people’s beliefs and increased feelings of national and religious differences.

Creating an environment of fear and general anxiety, with constant labelling of enemies was now expanded to nationalities. Ethnic intolerance, built by cleverly devised propaganda in the media, resulted in general support for a brutal war. Many studies and much research about the role of media in the former-Yugoslav conflict indicated that media, while serving the regime, produced war and hatred.

Fast forward to 2015. The media landscape has changed almost completely, but journalism still suffers from propaganda and its wicked elements. In the 21st century, where new technologies are bringing information – and journalism – to readers in new ways and faster than ever before, propaganda is alive and doing very well.

It is apparent that some media are in dire need of self-examination. There is a need to cleanse journalism of fear, propaganda and routine frustration. In the absence of critical journalism, democracy suffers and deliberate misinformation becomes the standard.

In the past 12 months my office has been heavily engaged in a campaign on several fronts to attack the root causes of propaganda and its all-too-likely consequences: ignorance, hate and hostility. My team has spent considerable time and resources working with Russian and Ukrainian journalists in confidence-building measures designed to bridge the gap between them. We have instituted training for young journalists from the two states on such topics as ethics in journalism, conflict reporting and propaganda.

The latest element in our campaign against propaganda was just published: Propaganda and Freedom of the Media offers an in-depth look at at the legal and historical basis against propaganda.

The report recommends that:

- Media pluralism must be enforced as an effective response that creates and strengthens a culture of peace, tolerance and mutual respect.

- Governments and political leaders should refrain from funding and using propaganda.

- Public service media with strong professional standards should be strongly supported in their independent, sustainable and accessible activity.

- Propaganda should be generally uncovered and condemned by governments, civil society and international organizations as inappropriate speech.

- The independence of the judiciary and media regulators should be guaranteed in law and in policy.

- The root causes of propaganda for war and hatred should be dealt with a broad set of policy measures.

- National and international human rights and media freedom mechanisms should be enabled to foster social dialogue in a vibrant civil society and also address complaints about incidents of hateful propaganda.

- Strengthening educational programmes on media literacy and internet literacy may dampen the flames that fire propagandists.

- Media self-regulation, where it is effective, remains the most appropriate way to address professional issues.

Propaganda does a disservice to all credible, ethical journalists who have fought for and, in some cases, given their lives to produce real, honest journalism. In sum, propaganda for war and hatred is effective only in environments where governments control media and silently support hate speech. A resilient, free media system is an antidote to hatred.

My hope is that the report Propaganda and Freedom of the Media will assist OSCE participating States, policymakers, academia and media professionals throughout the OSCE region and beyond.