9 Nov 2015 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan News, Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News

November is a month of historical anniversaries. Last Thursday was the annual commemoration of the foiling of the Gunpowder Plot and yesterday the UK fell silent to pay tribute to its war dead on Remembrance Sunday.

A much lesser-known date — at least to anyone outside Azerbaijan — is the country’s Flag Day, the celebration of the tricolour which was first adopted as the national flag on 9 November 1918.

The flag hoisted in the capital city of Baku was once confirmed by the Guinness Book of Records as being the tallest in the world. It flies on a pole 162 meters high and measures 70 by 35 meters. While the flag underwent a hiatus while Azerbaijan was part of the Soviet Union between 1920 and 1991, it is now a proud symbol of the country’s independence.

The tricolour consists of three horizontal stripes, each being deeply symbolic. The blue stripe stands for the Turkish origin of Azerbaijani people and the green stripe at the bottom expresses affiliation to Islam. Neither can be disputed. The red stripe in the middle, however, is problematic. It stands for progress, modernisation and democracy.

But Azerbaijan’s status as a modern democracy is less than convincing. Sure, the country has made some significant strides since the collapse of communism. It boasts a 98.8% literacy rate, and since the early 2000s spending on education has increased five-fold, for example.

However, there is an illusion of material progress in Azerbaijan. As Index on Censorship has been reporting, the country has experienced an unprecedented crackdown on human rights and freedoms.

Little over a week ago, Azerbaijan held a parliamentary election while an estimated 20 prisoners of conscience sat in prison. Azerbaijani journalist Khadija Ismayilova, who was sentenced to seven years and six months in jail in September for exposing state corruption, is one of them. The award-winning journalist was detained on 5 December 2014 and eventually convicted of libel, tax evasion and illegal business activity.

President Ilham Aliyev’s government has long claimed that “all freedoms are guaranteed in Azerbaijan“. Given his government’s lack tolerance for dissent, this clearly isn’t the case. Leyla Yunus, founder and director of the Institute for Peace and Democracy, and her husband, historian Arif Yunus — both outspoken critics of the government — have been detained since summer 2014 when they were arrested on charges of treason and fraud. On 13 August, the Baku Court on Grave Crimes sentenced Leyla to eight years and six months in prison and Arif to seven years in prison.

Democracy activist Rasul Jafarov, human rights lawyer Intigam Aliyev and journalist Seymur Hezi are also serving prison sentences on charges that were widely condemned for being politically motivated to silence outspoken critics of the government of President Aliyev.

The list of journalists and activists who have been arrested, abused, beaten and even killed goes on. In June 2015, on the eve of the inaugural European Games in Baku, activists from Amnesty International and Platform were banned from entering the country. Both organisations have been highly critical of Aliyev’s government, and its continuing targeting, jailing and prosecution dissenters. Even The Guardian was blocked from reporting on the games when its reporter was barred.

The ruling party in Azerbaijan may have won an outright majority in this month’s elections, cementing Aliyev’s hold on power. However, opposition parties boycotted the vote over concerns it was neither free nor fair. Even the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) refused to monitor the election after authorities severely limited its ability to observe the vote effectively. It marks the first time since 1991 that the OSCE has not monitored an Azerbaijani election and highlights that the situation in the country is far from progressive.

Flag Day is set against a backdrop of arrests and human rights abuses. If Azerbaijan is to earn its stripes, the authorities must uphold their human rights obligations, release all prisoners of conscience and allow for elections that meet basic democratic standards.

This article was posted on 9 November 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

30 Oct 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News, Serbia

The Association of Serbian Journalists reports that since 2013 there have been 65 attacks on Serbian journalists. Assailants in 11 of the incidents — around 17% of cases — have been prosecuted.

Believe it or not, a 17% conviction rate could be considered good news. But it isn’t enough.

International media organisations routinely assess that fewer than 10% of crimes committed against journalists worldwide result in prosecution. While the cavalier attitude by law enforcement and authorities to go after criminals gave rise to the phrase “impunity from prosecution,” many of us wonder if the term “immunity” might be more apt.

And that’s why I welcomed the initiative of Serbian authorities who, in early 2014, established a commission to support investigations into the deaths of Serbian journalists dating back to 1994, including Dada Vujasinović, Slavko Ćuruvija and Milan Pantić. In order to highlight the importance of their work and to raise the awareness of the importance of fighting impunity, my office supported the commission’s Chronicles of Threats campaign.

Ćuruvija, the owner of the newspaper Dnevni Telegraf and the magazine Evropljanin, was gunned down in front of his home in Belgrade in 1999. Thanks in part to the work of the commission, authorities re-opened the case last year and put four former state security officials under investigation for his murder. A trial is underway and while this is a start, his family and fellow journalists still need to see results.

This is why I why I wholeheartedly support all consciousness-raising efforts that take place on November 2 each year – the United Nations proclaimed International Day to End Impunity for Crimes Against Journalists which was initiated in 2013.

This landmark UN resolution condemns attacks on journalists and other media members. It also urges countries to do their utmost to prevent violence and make perpetrators accountable for their crimes, in order to promote a safe working environment.

But setting aside a day to cajole authorities to take the crimes against media seriously can only go so far. That is why the modest successes of the commission in Serbia provide a glimmer of hope that justice can be served.

But in order for societies to provide that safe working environment envisioned by the UN, a systematic array of steps must be undertaken at the local and national level. None of these steps are easy and their ability to succeed is questionable.

To begin with, local officials must be given the financial resources to conduct thorough investigations of all crimes committed. This is no small task in many of the 57 countries that comprise the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe — the region in which I work. Many of these nations have economies in transition, tax revenues are scarce and it’s a hard sell for authorities to suggest earmarking money to find justice for one class of victims when the needs of the whole community are not being adequately served.

Prosecutors and judges also need to be adequately trained to understand the importance of the fair application of existing criminal laws, especially when the rule of law in society is often buttressed only by a robust and independent media. This is the same media which is often critical of the prosecutors and judges who make up the judicial hierarchy.

In the end, getting past those hurdles may be seen, in retrospect, as the easiest steps. Because what’s really necessary to create a safe working environment is for society as a whole to accept that good journalism is necessary for a good society.

People must recognise that the free flow of information and ideas is essential in dynamic cultures and the secrecy and repression are antithetical to freedom and prosperity.

Creating a society where good journalism can flourish starts with making sure journalists can do their jobs and live to talk about it. And that means making sure that those who would run roughshod over journalists pay for their crimes.

This article was posted on 30 October 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

1 Oct 2015 | European Union, mobile, News

Dunja Mijatovic is the OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media. (Photo: OSCE/Micky Kroell)

Each autumn, more than 1,000 government and civil society representatives from 57 countries of the OSCE get together in Warsaw for a two-week discussion on a wide variety of human rights issues. The purpose of the meeting is to scrutinize each country’s performance on human rights standards they signed up to in areas such as free expression, free media and the panoply of basic rights prevalent in modern, liberal societies. It is designed to be a thoughtful and lively event that gets to the heart of implementing states’ commitments on the issues.

This year the first topic was dedicated to freedom of expression and the keynote speaker, Danish human rights lawyer Jacob Mchangama, raised “the issue du jour”: “Does a genuine commitment to tolerance, equality and nondiscrimination really depend on restricting the very freedom that has made possible the articulation and spread of new and progressive ideas from religious toleration in 17th century Europe, the abolishment of slavery, the equality of the sexes, criticism of apartheid and the rights of LGBT people?”

The issue, of course, is whether we need the spate of new laws enacted worldwide designed to somehow strike a balance between the right of free expression and the desire to weed out intolerance and hate in society.

In the wake of the Charlie Hebdo massacre in January, the answer to Mchangama’s question may well form the superstructure of the rights to free speech in the years to come.

We don’t need new laws. Indeed, it is time we stop looking at unbridled speech as something that promotes intolerance. We should see it as an opportunity to protect the rights of minorities and marginalised people to speak when the powerful are making distressing noises.

My reasoning is based on the simple view that when it comes to media freedom, those who govern least, govern best.

Even the best-intentioned laws cannot prevent intolerant speech. And general notions such as “hate speech” preferably should be avoided because they can be arbitrarily interpreted.

It is a decidedly New Age thought, likely first made popular by the 19th century essayist Henry David Thoreau in his essay on Civil Disobedience.

But today it is commonly thought that laws criminalising hate speech are beneficial to marginalized groups that need state protection. In reality, it is the marginalized groups who need the freedom of speak without fear of prosecution to press their causes and affirm their rights in society.

As Mchangama said in his address: “The freedoms that (sometimes) allow bigots to bait minorities are also the very freedoms that allow Muslims and Jews to practice their faiths freely. By further eroding these freedoms, no one is more than a political majority away from being the target rather than the beneficiary of laws against hatred and offence.”

Indeed, a significant development post-Charlie Hebdo has been the distressing comments by some that openly suggested the magazine’s staff “had it coming to them” for publishing illustrations satirising the prophet Muhammad. Just think of it: the victims of an outrageous act of silencing speech actually became, in some people’s eyes, the guilty ones.

It is time for some civility in the chaotic world of free speech. As I wrote shortly after the attack: “Intolerant speech should be primarily fought with more speech.” I still believe that is the foundation of any attempts to regulate content.

Following that line, I suggested, among other things, that participating states (the member countries of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe):

· Refrain from banning any form of public discussion or critical speech, no matter what it refers to;

· Take all possible measures to fight all forms of pressure, harassment or violence aimed at preventing opinions and ideas from being expressed or disseminated; and

· Eliminate restrictions to freedom of expression on the exclusive grounds of hatred, intolerance or potential offensiveness. Legislation should only focus on speech with can be directly connected to violent actions, harassment or other forms of unacceptable behavior against communities or certain parts of society.

My full statement on this issue.

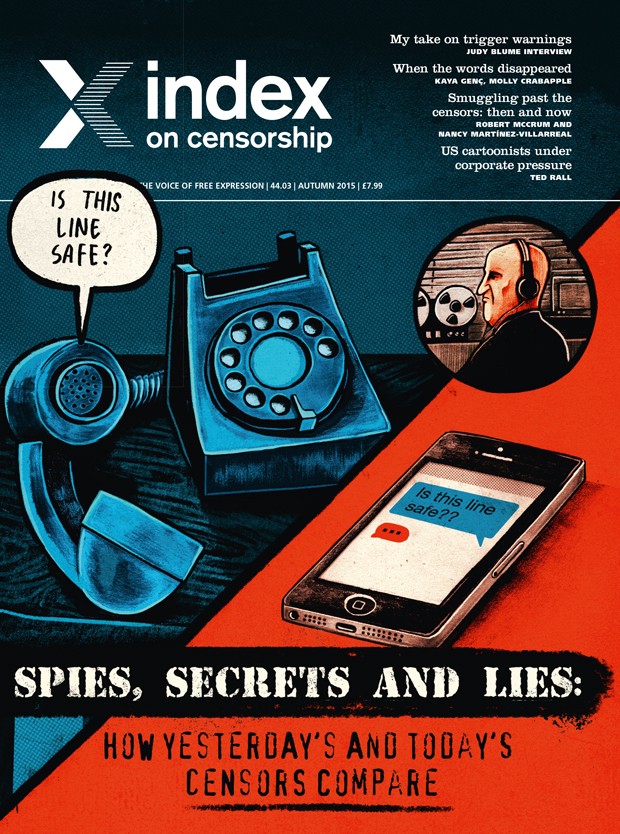

23 Sep 2015 | Magazine, mobile, Volume 44.03 Autumn 2015

Today the bulk of the media in the Balkans has “been bought by people with no history in, or understanding of, the media business; they promote narrow interests of their owners or new political elites; sometimes without even pretence of objectivity,” said Kemal Kurspahic, former editor of Oslobodjenje, an independent newspaper published during the Bosnian war, reflecting on the development of media freedom over the past 25 years.

While in the 1990s nationalism was the order of the day, today a whole host of challenges – including murky media ownership – face independent journalists across the region. The Balkan Investigative Journalism Network in Serbia, for instance, has documented the campaign against them from authorities and pro-government press on a dedicated website, BIRN Under Fire. Television journalist Jet Xharra and BIRN Kosovo took the government to court over the right to report on the prime minister’s accounts, and to set a legal precedent for press freedom in the state. But Xharra, country director of BIRN in Kosovo, said there is a sense of disbelief among those who had to report during war, that these kinds of battles still need to be fought.

“We cannot understand why, 20 years later, you have to deal with [such] a strain on your reporting,” said Xharra.

During the war years that tore Yugoslavia apart, press freedom, like pretty much every other aspect of society, experienced a profound crisis. Large swathes of the media in the former republics became propaganda tools for ruling elites, even before the fighting started. In fact, concerted media campaigns of hate and fear-mongering played an important part in priming people who had lived side by side for decades for war. As British historian Mark Thompson put it in his 1999 book Forging War, on the media’s role in the conflicts in Bosnia, Croatia and Serbia: “War is the continuation of television news by other means.”

|

Dangers of reporting in the Balkins

Attacks on journalists and journalism in the Balkans, compiled from Index’s Mapping Media Freedom project

SERBIA

Independent online news outlet Peščcanik has been targeted on several occasions after reporting in June 2014 that a senior minister had plagiarised parts of his doctoral dissertation. The site has faced distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks, and hackers have altered text and blocked IP addresses, thus preventing readers from accessing content.

MONTENEGRO

In May 2015, after reporting on corruption in local government, journalist Milovan Novovic’s car was vandalised. In June, journalist Alma Ljuca’s car was attacked in a similar way. This comes after a car belonging to the daily Vijesti was torched in early 2014.

BOSNIA

In December 2014, police raided the Sarajevo offices of news site Klix.ba, looking for a recording in which the prime minister of the country’s Republika Srpska entity spoke about “buying off” politicians. This came after the site’s director and a journalist were interrogated and asked to reveal their source for the recording, which they refused to do.

CROATIA

In May 2015, journalist and blogger Željko Peratović was attacked by three men outside his home, and hospitalised with head injuries. Peratović is known for his investigative reporting, and has covered the trial of two agents of the former Yugoslav Security Agency.

MACEDONIA

Deputy Prime Minister for Economic Affairs Vladimir Peshevski was filmed physically assaulting Sashe Ivanovski, a journalist and owner of the news site Maktel, who has been critical of the government.

SLOVENIA

In March 2015 photojournalist Jani Bozic received a suspended prison sentence for publishing a photo of Alenka Bratusek, then prime minster elect, which showed him receiving a congratulatory text message from a prominent businessman 20 minutes before results were announced.

KOSOVO

Express journalist Visar Duriqi, who has covered radical Islamists in Kosovo, has received a number of death threats, including threats of beheading.

Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project launched as in 2014 to record threats to media freedom throughout the European Union and EU candidate countries. It has recently expanded to cover Russia and Ukraine. |

Yet during the Balkan wars beginning in the 1990s there were local journalists who, in the face of enormous pressure, rejected nationalist and propagandist lines, and attempted to sift truth from lies and distortion. Beyond the daily struggle that came with just existing in a war zone, independent journalism was dangerous work. As Human Rights Watch points out in a new report on the state of media freedom in the Balkans, journalists who were, at the time, “critical of official government positions were often labelled as traitors or spies working on behalf of foreign interests and against the state”.

Serbia’s B92, a rare dissenting voice in a media landscape shaped by President Slobodan Milosevic’s propaganda strategy, is perhaps the most famous example of independent journalism. Set up in 1989 as a youth-focused radio station (later branching out into TV and web platforms), B92 bravely covered a turbulent time – from the war in Bosnia, to the Nato bombing of Serbia, to the protest movement that eventually saw Milošević ousted. For this, it was continuously hounded by the government. At one point in 1999 authorities commandeered its offices and radio frequency, forcing the station off air, before it could resume broadcasting from a different studio and frequency, under the name B2-92.

In Croatia, President Franjo Tudjman also made sure ultra-nationalism had a place in column inches and on airwaves. Feral Tribune, which started out in 1983 as a satirical supplement in the newspaper Slobodna Dalmacija, had other ideas. Under sustained pressure from the authorities, it covered stories of human rights and conflict that many other outlets avoided, in addition to its biting satire. It was taken to court, publicly burned, and one journalist was even drafted into the army after Feral published an edited photo of Tudjman and Milosevic in bed together on the front page.

Bosnia was the country in the region that would be by far the hardest hit by fighting. But even as war came to Sarajevo, independent journalism survived in some small way. Oslobodjenje, which started out as an anti-Nazi paper in 1943, had a track record of editorial independence. In 1988, staff for the first time voted for their own editor – Kemal Kurspahic – instead of accepting one appointed by the authorities. Just three years later they fought for their freedom again, this time in the constitutional court, as the newly elected nationalist parties agreed to adopt a law whereby they could appoint the editors and managers of Bosnian media. In 1992 came their toughest challenge yet. With the two towers of their office building under fire – in one night they lost six floors on one side and four on the other – they decided to go underground, and continue their work from a nuclear bomb shelter, with no newsprint supplies and no phone links.

“If dozens of foreign journalists could come to report on the siege of Sarajevo and Bosnian war, how could we – whose families, city and country were under attack – stop doing our job?” Kurspahic, now managing editor of Connection Newspapers, told Index. They felt an obligation to their readers: “We could not leave them without news at the worst time of their lives.”

Oslobodjenje even celebrated its 50th anniversary during the war, with 82 papers around the world printing some of their stories. With that they achieved “the ultimate victory”, Kurspahic said, “if the aim of the terror against Oslobodjenje was to silence us as a voice of multiethnic Bosnia”.

“People were getting killed, so we were reporting it. The risk was physical at that time to journalists,” Xharra told Index. Today she hosts Kosovo’s most watched current affairs programme, as well as fulfilling her role at BIRN Kosovo. But she cut her reporting teeth as a translator, fixer and field producer for UK broadcasters – the BBC and Channel 4 – during the Kosovo war. She recalled going through frontlines for a story, and hiding tapes from paramilitary checkpoints, painting a vivid picture of a time when practicing journalism in the western Balkans meant near constant risk of physical harm.

Journalists could be caught in crossfire, or targeted specifically for their work. Kurspahic remembers the Oslobodjenje reporter Kjasif Smajlovic in Zvornik, who sent his wife and children away, and stayed to report on the fall of the town until he was killed by Serbian paramilitary forces in April 1992. In 1999, Slavko Curuvija, known for his critical reporting, was shot 17 times in a Belgrade side street, just days after a pro-government daily had labelled him a Nato supporter. In many cases, there has been little to no accountability for such crimes, breeding a culture of impunity that still hangs over the region.

Because while the darkest days for press freedom in the Balkans came during wartime, peace has not brought the improved conditions many hoped for. At a talk in March, Dunja Mijatovic, the OSCE’s free expression representative, went as far as to say that the situation now is worse than in the aftermath of the conflicts.

And today the media itself remains part of the problem, especially when journalists turn on their colleagues. One prominent example is the story of BIRN Serbia. Following their critical investigation into a state-owned power company, Prime Minister Aleksandar Vucic labelled the group liars who had been funded by the EU to speak against his government. That attack was then taken forward by the pro-government Serbian press, including in the newspaper Informer. Just one example where the media has been a less than staunch defender of its own rights.

Data from Index’s Mapping Media Freedom project, which tracks media freedom across Europe, indicates that worries of threats to media rights are justified. In just over a year it has received more than 170 reports of violations from the countries of the former Yugoslavia. Incidents included a Croatian journalist who received a letter saying she would “end up like Curuvija”; a Bosnian journalist threatened over Facebook by a local politician; Kosovan journalists depicted as animals on several billboards; a Montenegrin daily that had a company car torched; a Macedonian editor who had a funeral wreath sent to his home; and a Slovenian who faced charges for reporting on the intelligence agency. Online and offline, physical and verbal, serious threats to press freedom remain, some 20 years on.

© Milana Knezevic

This article is part of the autumn issue of Index on Censorship magazine looking at comparisons between old censors and new censors. Copies can be purchased from Amazon, in some bookshops and online, more information here.