18 Dec 2013 | Uncategorized

Who would’ve thought the news earlier this month of YouTube being finally made accessible in Pakistan, albeit as a local search engine, would open a floodgate of criticism?

Minster of State for Information Technology and Telecommunications, Anusha Rehman certainly did not. She probably thought she had done a good turn — wooed many young digital rights activists who had long been demanding unblocking of the website and calmed others who had demanded blocking of objectionable content from it.

“Instead of installing costly filtration mechanisms, Google will easily be able to block blasphemous content on the request of the Pakistan government,” Rehman told the Senate’s Standing Committee on Information and Technology. “Saudi Arabia and Malaysia have also reached a similar arrangement with Google,” she added.

But Farieha Aziz, director at Bolo Bhi, a not-for-profit geared towards advocacy, policy and research in the areas of gender rights, government transparency, internet access, digital security and privacy, dismissed the news out right saying: “There is no arrangement between the company and the government, unlike the perception the government is projecting.”

“I don’t want a localised version. Remember what became of Disney in India with everything getting dubbed in Hindi! I would definitely prefer the original version,” said a resolute 12-year old Khadeja Ebrahim, a YouTube buff. “I love YouTube, my entire school loves YouTube and we hate the people who have blocked it,” she added vehemently.

Yasser Latif Hamdani, who had filed a case for unblocking the website, on behalf of digital rights campaigners Bytes For All is not too happy with the news. His concern is mainly constitutional.

“It is a matter of principle. I do not think it is alright that the government can decide what I should be able to view,” he said. To him this was a clear violation of Article 19, 19-A and 17 of the Constitution of Pakistan. “Therefore, I do not consider it a great service,” he concluded.

The young lawyer uses the popular video-sharing website to listen to debates on law, politics, constitution, philosophy and history. He accesses YouTube through virtual private networks(VPNs), but complains “the experience is just not the same”.

Nighat Dad, of the Digital Rights Foundation doesn’t find the move “encouraging” either and given “how different vague provisions of different laws and constitution have been misused in blocking the content on internet” in the Pakistan” is, in fact, quite wary. She warns: “I see a huge wave of internet blocking and censorship coming our way.”

“If it happens, it will be bad news!” pointed out Shahzad Ahmad, country director of B4A.

Simply put, said Ahmad, it means legalising censorship of digital content on this platform. “YouTube may then become like Facebook. You will only be able to see that content which authorities will allow us to see,” he explained.

Presenting a doomsday-like scenario, he further said: “A new war will erupt among religious factions and the stronger ones may demand a ban on the others. Human rights movement will suffer hugely, political expression will become much more difficult and alternate discourse will die.”

Many say this will put a stop to hate speech, a major issue stoking religious sects and minorities, in Pakistan, especially on social media.

Ahmad disagreed. “Banning hate speech will not end till perpetrators and banned outfits are taken to task. If you expect that banning their Facebook/Youtube or Twitter will solve the problem, then the answer is a no, a big no!” he said emphatically.

The blocking of YouTube in Pakistan, began last year on 17 September after the website refused to remove the blasphemous 14-minute video clip “Innocence of Muslim”.

The video had led to violent protests and demonstrations across the Muslim world, killing over 50 people.

Ahmad said the decision to block YouTube had nothing to do with upholding religious values or blocking blasphemous content. He suspects it had “political” underpinnings to it.

“The authorities have used this incident to strengthen censorship and filtering in Pakistan, and spent millions of dollars, a useless wastage of the public’s hard earned tax money, as nothing can be blocked on the Internet. Citizens have already resorted to VPNs and circumvention tools.

That is true. Over the past one year, hundreds of die-hard users of this website have relied on proxy servers to work around the ban.

“I just came back from China- and while Facebook and YouTube were banned everywhere, you can access them in Shanghai Freezone especially the Pudong district of Shanghai,” said Hamdani. “So even authoritarian regimes understand the futility of such censorship,” he added.

These proxy servers are passed on word of mouth and go viral within moments, but expire every few weeks. Then the process of passing the information starts all over again. “You can imagine our desperation,” pointed out Ebrahim.

But while she and her school friends are mostly using the website for downloading songs or cheat videos for games, there are hundreds who depended on it for their bread and butter.

“I can give you scores of examples of small traders, who marketed and “networked” for expanding their businesses on this free platform because they could not afford to advertise through the mainstream media. The Virtual University, an online learning institute, had uploaded thousands of lectures for its students to access; all that came to a halt. These lectures benefitted not just Pakistani students but millions of those living abroad. Now they have set up their own servers, and which I suspect must have been a huge investment” said Dad.

Toffee TV.com produces songs, stories and activities for children in the Urdu language. They went live on July 2011 and banked on YouTube to take it further and the latter did. It met with enormous success at schools, in homes and even among speech therapists, but saw a huge slump in its business. Before the ban was imposed, TOFFEE was uploading two new video programmes per week with 100,000 new visitors a month and serving five times those many repeat visitors.

The minister for IT said that the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority has been tasked with drafting an ordinance that would provide intermediary liability protection to Google/YouTube, thereby not holding the company responsible for what users choose to upload to the platform.

Bolo Bhi is quite disturbed by this news. “Why is PTA, a regulatory authority that deals with enforcement and not policy making, being asked to draft the ordinance?” it asked in a press statement. It also asked what became of the expensive filtering equipment that the government had acquired for its telecommunication networks.

2 Dec 2013 | Digital Freedom, News and features, Pakistan, Politics and Society

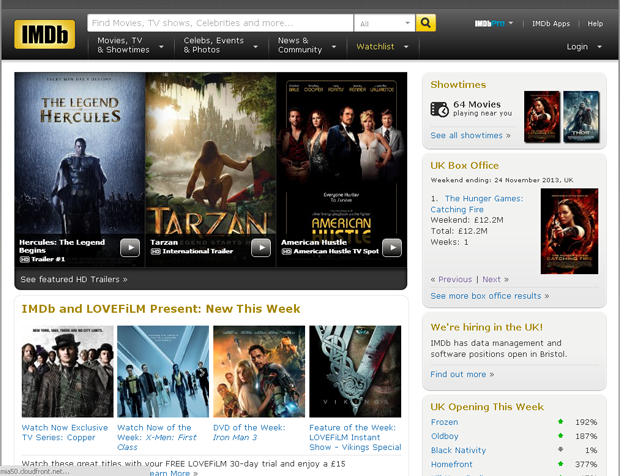

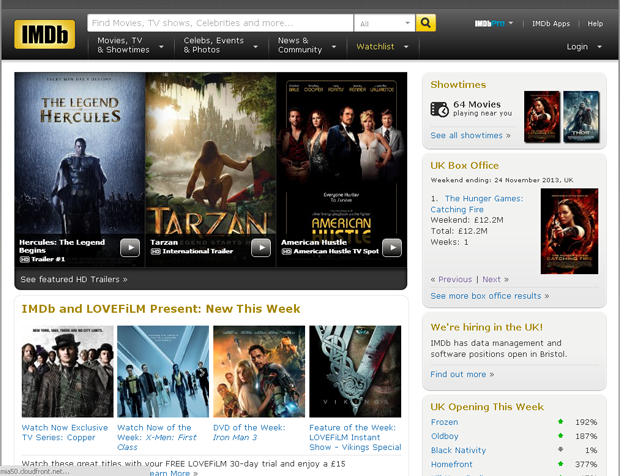

Urooj M, a former DJ on a Pakistani FM radio channel, also a film aficionado, was incredulous when she found the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) had blocked the Internet Movie Database (IMDb).

She tweeted: “SERIOUSLY #PAKISTAN, WHY ON EARTH WOULD YOU BAN #IMDB!!! COME ON, SERIOUSLY!!!???!!!! #FirstYoutubeNowIMDB #WTF.”

This widely used online entertainment news portal, a prominent source of reliable news and box office reports regarding films, television programmes and video games from all over the world, was blocked on 19 November, but the ban was lifted by 22 November.

Pakistan is notorious for blocking websites. It has banned more than 4,000 websites for what it considers objectionable material, including YouTube, in 2012 for a film that was deemed blasphemous by Muslims around the world. In 2011, in a particularly ill-thought-out move it announced censoring text messages containing swear words. In 2010, after a decision by the Lahore High Court, Facebook was blocked as a reaction to the ‘Everybody Draw Muhammad’ page that was seen as offensive to the prophet.

Users were given no reason for this sudden and selective ban. However, Omar R. Quraishi, a journalist had tweeted: “PTA official declined to give specific reason for ban on IMDB – said is placed for 3 reasons: “anti-state”, “anti-religion”, “anti-social”.

While these “targeted bans” are small irritants in his life, as he can easily by pass them, Ali Tufail, 26, a Karachi-based lawyer, finds them wrong on principle as he sees them infringing upon the fundamental rights of the citizen as given in Article 19 and 19 A of Pakistan’s Constitution.

He said the government must give users sound “reasons” why they block a certain website and “what benchmarks or what standards are used to come to the decision to enforce these sudden bans” and if there is a committee that takes these decisions, “we must be told who these people are.”

The same was endorsed by Nighat Dad of Digital Rights Foundation (DRF). “We strongly oppose any form of censorship employed on citizens, curbing their basic right to information.”

However, netizens believe the ban was enforced to block the movie trailer for The Line of Freedom, a film that highlights the issue of the crises in Balochistan province showing Baloch separatists abducted by Pakistani security agencies without charges in a bid to stamp out rebellion.

“Our team did a quick survey with the help of tweeters around the country,” said Dad. “We checked various other movie titles but only Line of Freedom seemed to be blocked on IMDb and several other websites were accessible otherwise.” The DRF termed it an “unprecedented event” because the government had “used all sorts of means to curb the dissidents’ views” from Balochistan.

“I didn’t even know there was a movie by this title which was giving the government so much heartburn and so I just had to see what was so unsavoury that the government had to block the entire website,” said Dad who watched the whole 30 minutes or so of it by circumventing the various firewalls. “This is what happens, when you forcibly close the internet, word gets around and people get curious!”

Malik Siraj Akbar, editor of the online Baloch Hal, who sought asylum in the United States, is not surprised at the ban. His own newspaper was blocked in November 2010 and even now the ban has not been completely lifted, he says. “Since 2010, it has been available in some parts of the country and not others and access has not been very consistent,” he said adding there were hundreds of other Baloch websites, “mostly those supportive of the nationalists that have been blocked”.

But Tufail added: “This is one battle which the government would find difficult to win as newer, maybe more objectionable [to Pakistani state] websites, will keep popping up which they would never be able to keep pace with,” terming such bans an “exercise in futility”.

There could be some truth in the story of the ban on the Baloch film. Because their voices remain unheard, several family members made a 700km journey on foot from Quetta to Karachi to see if that would make a difference.

Naziha Syed Ali, a journalist at English-language daily Dawn, had recently visited Awaran, a stronghold of the separatists in Balochistan, which had been badly affected by the earthquake on September 24. She said she got a sense of “hostility expressed mainly towards the army and paramilitary rather than Pakistan per se. Then again, the army is seen as a symbol of the country, so it’s pretty much the same thing.”

Ali said “More than fear, they don’t want to take help from what they see as an occupation force.”

According to her the “feelings of alienation have been greatly exacerbated by the issue of the missing people and the kill-and-dump tactics”.

In addition, while Ali found there to be “sufficient food for now”, there was dire need for health services and proper shelter “as the tents that have been distributed are not warm enough for winter”.

The problem is the army is not allowing international and local non-governmental organisations to carry out any relief work there. Instead, the charities run by religio-political organisations and even banned outfits are seen freely roaming about. For years, the state has kept a stony silence over the issue of the disappearances of the Baloch nationalists. Rights group say if the state lets the various organisations into the region, their dark secrets about grave human rights abuses, for now a national shame, may become a problem for it on the international front.

This article was published on 2 Dec 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

22 Nov 2013 | Americas, Asia and Pacific, Azerbaijan News, Europe and Central Asia, News and features

Tomorrow is International Day To End Impunity. “When someone acts with impunity, it means that their actions have no consequences” explains IFEX, the global freedom of expression network behind the campaign. Since 1992, 600 journalists have been killed with impunity — that is 600 lives taken with all or some of those culpable not being being held responsible. Countless others — writers, activists, musicians — have joined their ranks, simply for exercising their right to freedom of expression.

This year has only added to the grim statistics. By the middle of January, six journalists had already been murdered. We are now getting close to the end of 2013, and 73 more journalists and two media workers have suffered the same fate — 48 in cases directly connected to their work, 25 with motives still unconfirmed. Out of these, 15 were killed without anyone — perpetrators or masterminds — convicted.

Russia is notorious for its culture of impunity. In July this year, Akhmednabi Akhmednabiev, a Russian journalist reporting on human rights violations in the Caucasus, was shot dead. In 2009 he had been placed on an “execution list” on leaflets distributed anonymously, and had in the past also received death threats. In January he survived an assassination attempt which local authorities reportedly refused to investigate. His case is still classed as murder with impunity.

Pakistan is also an increasingly dangerous place to work as a journalist. Twenty seven of the 28 journalists killed in the past 11 years in connection with their work have been killed with impunity. In the last year alone, seven journalists have been murdered. Express Tribune journalist Rana Tanveer told Index he has received death threats and been followed for reporting on minority issues. In October, Karak Times journalists Ayub Khattak was gunned down after filing a report on the drugs trade.

In July, Honduran TV commentator Aníbal Barrow was kidnapped together with his family and a driver. The others were released, but after two weeks, Barrow’s body was found floating in a lagoon. He was the second journalists with links to the country’s president Porfirio Lobo Sosa — they were close friends — to have been killed over the past two years. Four members of the criminal group “Gordo” were detained in connection with the case, but at one point, there were at least three other suspects on the run.

In September, Colombian lawyer and radio host Édison Alberto Molina was shot four times while riding on his motorcycle with his wife. His show “Consultorio Jurídico” (The Law Office), aired on community radio station Puerto Berrío Stereo, and often took on the topic of corruption. The Inter American Press Association in October called on authorities to open “a prompt investigation into the murders” of him and news vendor and occasional stringer José Darío Arenas, who was also killed in September.

Meanwhile in Mexico, a country for many synonymous with impunity for crimes against the media, three journalists were murdered in 2013. The state public prosecutor’s offices has yet to announce any progress in the cases of Daniel Martínez Bazaldúa, Mario Ricardo Chávez Jorge and Alberto López Bello, or disclose whether they are linked to their work. Notorious criminal syndicate Zetas took responsibility for the murder of Martínez Bazaldúa and warned the police about investigating the case. He was a society photographer and student, only 22 at the time of his death. Chavez Jorge, founder of an online newspaper, disappeared in May and his body was found in June, but in August the state attorney’s office said they did not have a record of his death. López Bello was a crime reporter who had published stories on the drugs trade.

This year, 20 journalists — from Naji Asaad in January to Nour al-Din Al-Hafiri in September — have also lost their lives covering the ongoing tragedy of the Syrian civil war. Their loved ones, like those of all the civilians killed, will have to wait for justice.

It is also worth noting that while an unresolved or uninvestigated murder is the most serious and devastating manifestation of impunity, it is not the only one. Across the world, journalists are being attacked and intimidated without consequences. In August there was a two-hour long raid on the home of Sri Lankan editor and columnist Mandana Ismail Abeywickrema, who recently started a journalists’ trade union. Despite her receiving threats related to her work prior to the attack, it was labelled a robbery by the police. Bahraini citizen journalist Mohamed Hassan experienced similar incident, also in August, when he was arrested and his equipment seized during a night-time raid. His lawyer Abdul Aziz Mosa was also detained and his computer confiscated, after tweeting about his client being beaten. In October, a group of Azerbaijani journalists were attacked by a pro-government mob while covering an opposition rally in the town of Sabirabad. One of the journalists, Ramin Deko, told Index of regular threats and intimidation.

International Day To End Impunity is a time to reflect on these staggering figures and the tragic stories behind them. More importantly, however, it represents an opportunity to stand up and demand action. Demand that Russia’s President Vladimir Putin, Mexico’s President Enrique Peña Nieto, Pakistan’s President Mamnoon Hussain and the rest of the world’s leaders provide justice for those murdered. Demand an end to the culture of impunity in which journalists, writers, activists, lawyers, musicians and others can be intimidated, attacked and killed simply for daring to speak truth to power. Visit the campaign website to see how you can take action.

20 Nov 2013 | News and features, Pakistan, Politics and Society

Members of Baloch Shohada Committee lighten candles during a protest against Baloch genocide on the occasion of Youm-e-Shohada-e-Baloch. (ppiimages / Demotix)

Farzana Majeed holds Pakistani media as responsible for the disappearances of thousands of Baloch nationalists as the state security apparatus, labelling it a “very willing accomplice.”

29-year old Majeed is among the two dozen people on a long march organised by the Voice of Missing Baloch Persons (VOMBP) which has protesting for the last four years. They are demanding the return of their loved ones, who they allege have been illegally apprehended and detained by Pakistan’s intelligence and security agencies.

“The media should be the voice of the victims and report on the atrocities committed on our people; instead they are pressured into silence by the state”, she said.

The march began on October 27 from Quetta in Balochistan covering a distance of almost 700 km, and will reach Karachi, in the Sindh province, by the end of the week. There, outside the Karachi Press Club, they will hold an indefinite sit-in and hunger strike. The marchers started with covering anywhere between 35 to 40 km/day, but blisters and illness are slowing down progress to barely 25km a day.

The mineral-rich Balochistan is the largest of the four provinces of Pakistan, and was an independent state until 1947, when Pakistan annexed its eastern side and Iran its western side. For many Baloch families, since the disappearances began more than a decade back, life has not been the same.

According to Qadeer Baloch who founded the VOMBP, around 18,000 Baloch nationalists, including doctors, professors, politicians and students, have been abducted since 2001. “We have received mutilated corpses of 1,500 of them.”

Farzana Majeed’s brother Zakri was abducted four years ago from the city of Mastung. He was the vice president of the Baloch Students Organisation (Azad), a nationalist student group raising awareness of the rights of the Baloch on campuses. Despite holding a double master’s in biochemistry and Balochi language, Majeed said her life has been put on “on hold” and her three siblings and mother rendered “homeless” since Zakri’s disappearance. She hasn’t heard any news of him for three years.

Baloch’s own son Jalil Reiki, the information secretary of Baloch Republican Party, was picked up in 2009. Almost two years and eight months later, his tortured and bullet-riddled body was found.

“The disappearances started way back in 2001 during president Pervez Musharraf’s rule but this human rights abuse came on public radar in 2004-05 after the women — mothers, sisters and wives — started coming out and began protesting,” explained Malik Siraj Akbar, editor of online English newspaper The Baloch Hal. He said Baloch women hardly ever come out publicly and so when they did, they were bound to be noticed.

“Except for BBC, and a couple of English national dailies, no other media is supporting us,” said Baloch, who is leading the march. The lukewarm response, however, has failed to deter the marchers. “It is a way of teaching our coming generation the value of speaking up,” Baloch told Pakistan’s Dawn newspaper.

“Some of our friends in the media have disclosed that the intelligence agencies have warned and threatened them from covering our peaceful protest; others have been told that we are causing bad publicity internationally,” he added.

Akbar, who has taken asylum in the United States after most of his friends and colleagues were killed, said: “I know the agencies have been threatening the protesters with dire consequences and forcing them to shut down their camps and end the rally.” However, he added that he was not aware of any “threats or pressure on the media from the agencies and the government”.

But according to the chairperson of the independent Human Rights Commission of Pakistan, Zohra Yusuf, “journalists in Balochistan are under pressure from the Frontier Corps [federal reserve military force], the Baloch separatists as well as the religious extremists”.

Mazhar Abbas, a former secretary general of the Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists, speculated that the poor coverage of the march, as well as the issue of disappearances, may be due to the “influence used on media barons by the intelligence agencies”.

While he emphasised the electronic media had covered the Supreme Court hearings around the issue at length, he found it had never been tackled properly from a human rights angle. He lamented the “non-professional” attitude of the print media which did not find the issue grave enough to do investigative reporting on it.

The missing are no longer an “exciting” story so they are not covered by the national media, Akbar said. “Unfortunately, nobody seems to care much about it in a country where dozens of people are killed every day,” he said.

Zohra Yusuf also said the urban-based media did not seem particularly interested in the issue as it was more “ratings oriented”.

As for the on-going march not able to attract media’s attention, Abbas suggested that had it been led by “known political or nationalist figures”, it would have automatically lured the media to it.

A recent HRCP report, based on a fact-finding mission to Balochistan, stated that while the people of the province have pinned their hopes on the new government to address the problems, especially regarding the “grave human rights violations”, many do not see any visible policy change “within the security and intelligence agencies”, as the “kill-and-dump policy” continued.

According to Malik Siraj Akbar, while the ongoing long march isn’t any different from past demonstration, it is the “first major protest” since the new governments in the province and the centre took over the reins.

“The long march reflects the new government’s failure to resurface the missing persons and normalise the situation in Balochistan,” he pointed out.

This article was originally published on 20 Nov 2013 at indexoncensorship.org