Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Acrassicauda concert at The Roxy in Hollywood, 10 June 2010. Credit: Flickr / Bruce Martin

Underground music scenes have begun sprouting up in many countries around the world in the last few years, where previously no such thing existed. These movements have managed, in many cases, to continue despite a continuing trend of censorship in the arts and government repression. Whether it be punks in Indonesia rebelling against Sharia law or hip-hop artists in Mumbai rapping about independence from Britain, people all over the world are fighting for their right to artistic freedom. Here are a few cities around the world where musicians refused to be silenced.

Even after social activist and creator of The Second Floor, a cafe that promotes discussion, performance and art, Sabeen Mahmud was murdered by armed motorcyclists in Karachi in April 2015, the experimental and electronic music culture has continued to grow. Refusing to be intimidated into silence, artists like Sheryal Hyatt, who records as Dalt Wisney and founded Pakistan’s first DIY netlabel, Mooshy Moo, and the producing pair of Bilal Nasir Khan and Haamid Rahim, who created the electronic label and collective Forever South, are challenging conventional ideas about the music culture in Karachi.

Punk music is one of the ultimate forms of expressing disdain for a system of oppression, so it comes as no surprise that so many youths in Indonesia have embraced the genre with a passion. The punk scene, which grew exponentially following the 2004 tsunami when a great many lost family members and help from the government was less than forthcoming. The hostility and discrimination against the punk subculture came to a head in 2012 when police rounded up 64 youths at a concert, arrested them and took them to a nearby detention centre to have their mohawk hairstyles forcibly shaved. Despite this, bands like Cryptical Death continue to promote their scene and pen songs about resisting repressive government figures.

The vitality of punk music is also present in Burma, where musicians have been advocating for human rights through fast-paced music since around 2007. No U Turn and the Rebel Riot are popular punk groups that routinely rail against a government that they feel is repressive and unjust. No U Turn sounds like a resurrection of Bad Religion-meets-Naked Raygun with a blend of biting lyrics and punishing speed.

Indian hip-hop pioneers have been appearing more and more in the last 10 years, with Abhishek Dhusia, aka ACE, forming Mumbai’s Finest, the city’s first rap crew, and Swadesi, another local group whose work they think represents feelings and ideals of many young people in the city. Swadesi, in particular, advocates for social justice within their band’s mission, with working for NGOs and organising events being an important element of their group.

Musicians in Iraq have faced a variety of oppressive control, ranging from young people being stoned to death by Shi’ite militants for wearing western-style “emo” clothes and haircuts to Acrassicauda, a popular heavy-metal band from Baghdad, receiving death threats from Islamic militants. Acrassicauda had to flee the country a few years after the USA invaded Iraq, going first to Syria and then to the USA, where they were given refugee status and from where they now continue to make music. They have hopes of touring the Middle East soon but have no idea when they will be able to return to Iraq.

Index on Censorship has teamed up with the producers of an award-winning documentary about Mali’s musicians, They Will Have To Kill Us First, to create the Music in Exile Fund to support musicians facing censorship globally. You can donate here, or give £10 by texting “BAND61 £10” to 70070.

The anti-terror charges against reporters for Vice News in Turkey are not isolated. In recent years, a number of countries have used broad anti-terror laws to restrict the freedom of the press.

Turkey

British journalists Jake Hanrahan, left, and Philip Pendlebury and Iraqi translator and journalist Mohammed Ismael Rasool were filming clashes between pro-Kurdish youths and security forces, according to Vice. (Photos: Vice News)

Two British journalists and a local fixer working for Vice News were charged on Monday 31 August in Turkey with “working on behalf of a terrorist organisation”. They will remain in detention until their trial, the date of which has not yet been announced.

The journalists Jake Hanrahan, Philip Pendlebury and Iraqi translator and journalist Mohammed Ismael Rasool were filming clashes between security forces and youth members of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) in the south-eastern city of Diyarbakir on Thursday when they were arrested.

Turkey’s broad definition of terrorism means that any journalist reporting on PKK activities or Kurdish rights can be charged with the offence of making “terrorist propaganda” and jailed.

Index on Censorship Chief Executive Jodie Ginsberg said: “Coming just days after the unjust sentencing of three Al Jazeera journalists in Egypt, these latest detentions of journalists simply for doing their jobs underlines the way in which governments everywhere can use terror legislation to prevent the media from operating.”

Egypt

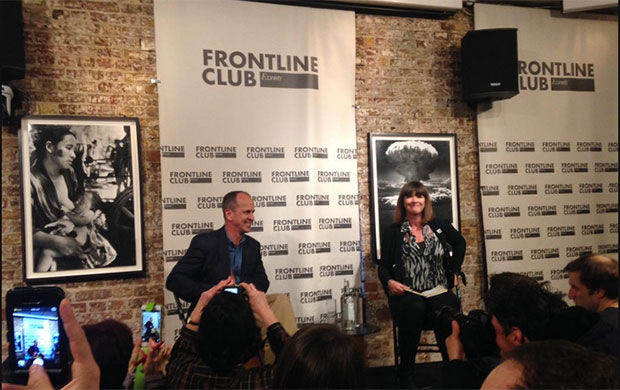

Peter Greste spoke to a Frontline Club audience about his arrest and detention in Egypt. (Photo: Milana Knezevic / Index on Censorship)

Egypt remains a cause for concern when it comes to press freedom: on 29 August 2015 Al Jazeera journalists Mohamed Fahmy, Peter Greste and Baher Mohamed were sentenced to three years in prison. The journalists were found guilty of of “broadcasting false information” and “aiding a terrorist organisation” – a reference to the Muslim Brotherhood.

The sentencing came just weeks after President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s government passed an anti-terror law setting a fine of up to 500,000 Egyptian pounds (£41,600) for journalists who stray from government statements or spread “false” reports on attacks or security operations against armed fighters.

Jordan

Abdullah II of Jordan at a conference in Amman in 2013. Ahmad A Atwah / Shutterstock.com

Jordan introduced a new “anti-terror” law in 2006 prohibiting, among other things, the engagement in “acts that expose the kingdom to risk of hostile acts, disturb its relations with a foreign state, or expose Jordanians to acts of retaliation against them or their money”. The charge carries a prison sentence of three to 20 years. The law was amended in 2014 to , broaden the definition of terrorism.

Interpretation of the law has been varied. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), in April 2015 a journalist was jailed for criticising the Saudi-led bombing of Houthi forces in Yemen. Another journalist was detained in July 2015 for breaking a recent ban on coverage of a terror plot. Earlier in 2015, an activist who criticised the royal family’s support of Charlie Hebdo on Facebook was sentenced to five months in jail under the anti-terror law.

Tunisia

One month after June’s terrorist attack on Sousse beach killing 38 tourists, for which ISIS claimed responsibility, Tunisia approved new anti-terror legislation.

Under the legislation, website editor Nour Edine Mbarki was charged in connection with publishing a photograph of a car that purportedly transported a gunman behind the beach attack. According to the CPJ, he was charged under Article 18 of the law with “complicity in a terrorist attack and facilitating the escape of terrorists,” which carries a prison term of between five and 12 years. He is currently awaiting a trial date.

Human Rights Watch said the new anti-terror bill “would open the way to prosecuting political dissent as terrorism, give judges overly broad powers, and curtail lawyers’ ability to provide an effective defence”.

Pakistan

Rights groups have long criticised Pakistan’s notorious anti-blasphemy laws for their effect on freedom of expression in the country. But strengthened anti terror legislation is also impacting the way journalists operate in the country.

In June, three Pakistani journalists were charged under the Anti-Terrorism Act, reportedly for covering the activities of a dissident politician, according to the Pakistan Press Foundation. A year before, a TV anchor was also charged under the law.

One to watch: Kenya

Following two separate attacks by al-Shabab militants in December, Kenya’s President Uhuru Kenyatta signed into law a new security bill that could curtail press freedom. Under the new law, journalists could face up to three years in jail if their reports “undermine investigations or security operations relating to terrorism” – or even if they published images of “terror victims” without police permission.

This hasn’t come into play yet – in February, the Kenyan High Court threw out several clauses, including those that could impact media freedom. The government has said it would consider lodging an appeal.

This post was written by Emily Wight for Index on Censorship

This article was posted on 1 September 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

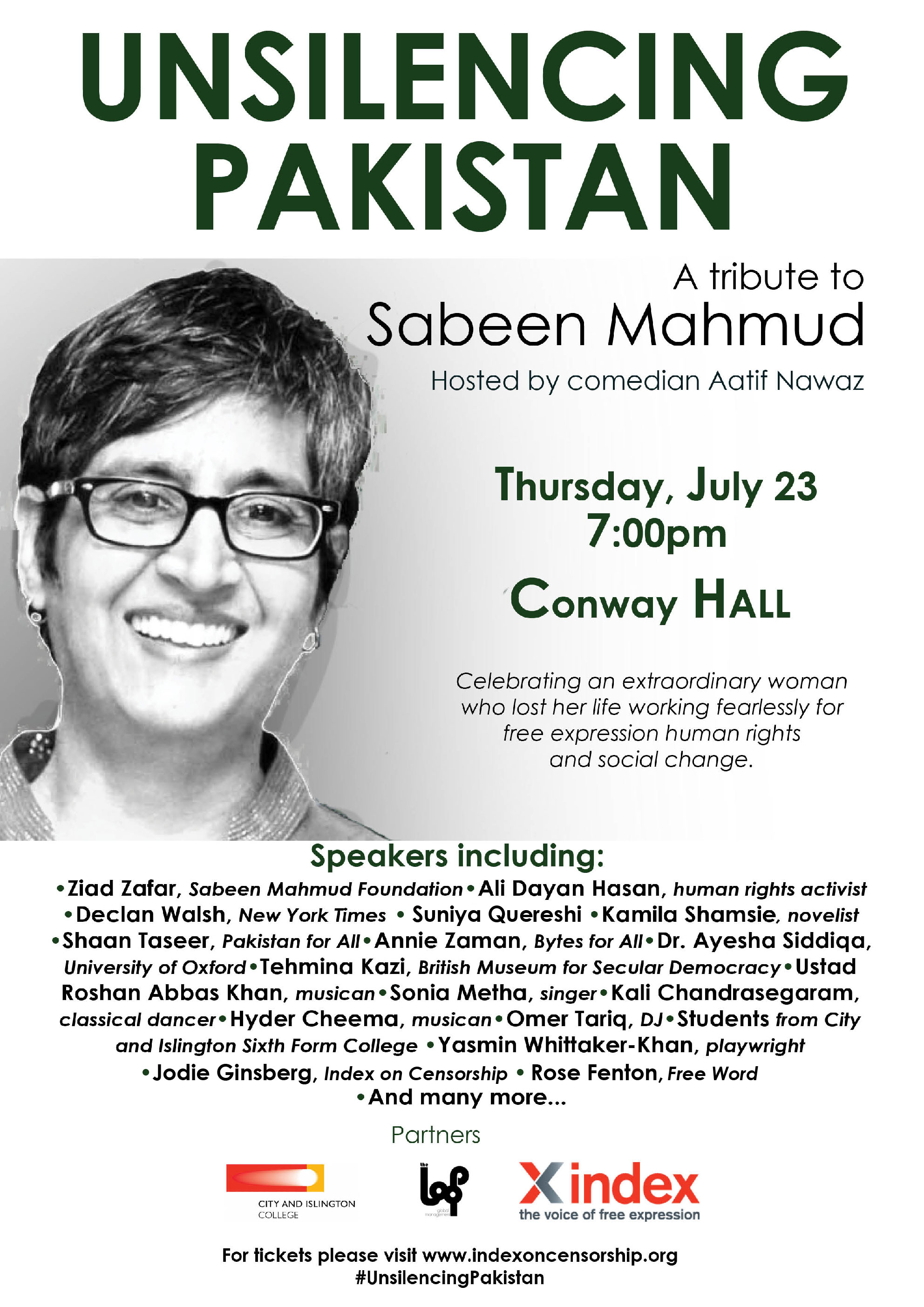

Sabeen Mahmud was killed on 24 April 2015. (Image courtesy Qismat Foundation)

“Tonight, please don’t forget to laugh and dream out loud, that would be the best tribute you could pay to Sabeen”, said Mahenaz Mahmud via video at Unsilencing Pakistan, an event co-hosted by Index on Censorship at London’s Conway Hall on Thursday 23 July.

Three months earlier, Mahenaz’s daughter Sabeen Mahmud was killed by gunmen. On 24 April 2015, travelling home from hosting a panel discussion about the missing people of Balochistan two men on motorbikes surrounded the car and opened fire. Mother survived, daughter didn’t.

Sabeen Mahmud had been a prominent ‘social activist’ and human rights advocate including founding The Second Floor, a cafe dedicated to being a safe space for community discussion. Three months on from her murder, the London event was a tribute to a woman described by so many as an inspiration, a fantastic listener and a champion of free speech and freedom of expression.

Hosted by comedian Aatif Nawaz, the evening was a celebration of Mahmud’s life and Pakistani culture. Multiple speakers, many of whom knew Mahmud well, shared their thoughts on her work and the issues she confronted as she worked to encourage greater openness in Pakistan.

The event began with the trailer from forthcoming documentary Silencing Sabeen, a look back on the life and tragic death of a woman loved by so many. All of those who were close to Mahmud showered praise upon her and told anecdotes of a woman dedicated to the cause of free expression. BBC journalist Ziad Zafar, founder of Pakistan for All and a member of the newly launched Sabeen Mahmud Foundation’s board, said: “She was at the forefront of every progressive movement that has taken precedence in Pakistan in the last decade”. Dr Ayesha Siddiqa from the University of Oxford, who had met Sabeen on a number of occasions, said: “Conversation doesn’t weaken Pakistan. Sabeen knew that to free Pakistan, you need to unsilence it.”

Ziad Zafar on #SabeenMamud Love was her moral compass and driving force #UnsilencingPakistan live: http://t.co/fxuwfsjavT

— Index Events (@IndexEvents) July 23, 2015

Ziad Zafar on #SabeenMamud The power of an ordinary life lived well #UnsilencingPakistan live: http://t.co/fxuwfsjavT

— Index Events (@IndexEvents) July 23, 2015

Dr Ayesha Siddiqa: Pakistan is becoming more silent. We should not have ghosts #UnsilencingPakistan live: http://t.co/fxuwfsjavT

— Index Events (@IndexEvents) July 23, 2015

Suniya Qureshi says #SabeenMamud could not say no to doing the right thing #UnsilencingPakistan http://t.co/fxuwfsjavT

— Index Events (@IndexEvents) July 23, 2015

Ali Dayan Hasan, a Pakistani human rights activist, knew Mahmud as a child and watched her grow into a beautiful woman. Of Karachi, her beloved birthplace, he said: “Her life, her achievement, her death is all quintessentially about the city that she came from”.

#SabeenMahmud was not an activist , she was an humanist. says @AliDayan #UnsilencingPakistan pic.twitter.com/nh1yWc8N02

— Syedih (@SyedIHusain) July 23, 2015

.@AliDayan: It is an obscenity for me that #SabeenMahmud is dead and I am alive #UnsilencingPakistan http://t.co/fxuwfsjavT

— Index Events (@IndexEvents) July 23, 2015

Childhood friend and Index on Censorship magazine contributor Kamila Shamsie described their blossoming friendship from the moment they met at Kindergarten. She had recently asked friends and colleagues of Sabeen to send her written praise of their late friend. One said: “Her passion was contagious,” while another said: “Sabeen would never have kept the spoils of victory, even if she had fought alone.”

Now speaking #UnsilencingPakistan, novelist @kamilashamsie ‘@thesecondfloor is an embodiment of Sabeen’s generosity in bricks and mortar’

— Cat Brogan (@catherinebrogan) July 23, 2015

The evening’s speakers also explored the state of Pakistan’s democracy and numerous attacks on free speech in recent times. Tehmina Kazi from British Muslims for Secular Democracy warned that “universal human rights have been tossed aside and been replaced by cultural relativism. The very people who need to have their eyes wide open have their eyes wide shut”.

Tehmina Kazi: Pakistani women share the experience of marginalisation #UnsilencingPakistan http://t.co/fxuwfsjavT

— Index Events (@IndexEvents) July 23, 2015

Shaan Taseer of Pakistan For All, whose father Salmaan was murdered for his opposition to Pakistan’s blasphemy law, spoke forcefully about standing up to nationalist and religious figures like Abdul Aziz.

.@ShaanTaseer: If there’s one way to honour her memory: We must never stop providing the alternative narrative #UnsilencingPakistan

— Index Events (@IndexEvents) July 23, 2015

Shaan Taseer @PakistanForAll #UnsilencingPakistan ‘in Pak death threats are not metaphors … we need new narratives’ pic.twitter.com/1Ne7lLZpTq

— Cat Brogan (@catherinebrogan) July 23, 2015

The New York Times Pakistan Bureau Chief Declan Walsh, who now operates from London after having his visa cancelled by Pakistani authorities, spoke of how, on first arriving in Pakistan in 2004, he was struck by the vibrancy and free speech of the press even though at the time it was under military rule. He called Mahmud’s murder a “very dark watershed in the decline of free speech in Pakistan in the last ten years.”

Declan Walsh at #UnsilencingPakistan @declanwalsh #London a tribute to #SabeenMahmud pic.twitter.com/2Jr9wb0Shx

— Ali Bin Zafar (@alibzafar) July 23, 2015

Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index on Censorship, said: “It takes bravery to be a dissenter at any time but it takes a special kind of courage to stick your head above the parapet in times of danger.”

Other speakers on the night included Annie Zaman from Bytes For All and Suniya Qureshi of the Qismat Foundation.

Annie Zaman of @bytesforall for me #SabeenMahmud is a martyr for free speech #UnsilencingPakistan http://t.co/fxuwfsALnr

— Index Events (@IndexEvents) July 23, 2015

Paying tribute to Mahmud’s passion for the Art, and T2F’s ongoing role as a gallery and performance space, Pakistani singers and dancers including Kali Chandrasegaram, Hyder Cheema and Ustad Roshan Abbas Khan were also on the programme. In a fitting nod to Mahmud’s well known support for young people and future generations, three students from City and Islington Sixth Form College were also invited, bringing diversity to the bill.

Co-organisers of the event, Yasmin Whittaker-Khan and Anneqa Malik thanked the audience and Index on Censorship, encouraging action to prevent more tragedies like Mahmud’s.

Malik, a personal friend of Mahmud’s, implored people to take personal responsibility for drawing people’s attention to the plights of those in Pakistan themselves rather than shouldering it on to others. She said: “Please don’t let them silence us. Please don’t let them silence Sabeen.”

This article was posted on 24 July 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

In May 2007 Sabeen Mahmud founded The Second Floor (now known as T2F), a coffee house and “community space for open dialogue” in Karachi, Pakistan.

In April 2015, Mahmud was shot dead by unidentified gunmen. Travelling home after hosting a panel discussion on the missing people of Balochistan, a poor but resource rich province of Pakistan, armed motorcyclists surrounded her car and opened fire.

Three months after this brutal act, Index on Censorship are working together with Yasmin Whittaker-Khan, Anneqa Malik and the Sabeen Mahmud Foundation to commemorate and celebrate an extraordinary woman.

Featuring prominent speakers alongside live art, music, poetry and Pakistani food.

Hosted by British-Pakistani stand-up comedian and TV presenter Aatif Nawaz. With:

When: Thursday 23 July, 7:00pm

Where: Conway Hall, 25 Red Lion Square, London WC1R 4RL (Map/directions)

Tickets: Free, book here

Presented in partnership with Conway Hall Ethical Society and the Sabeen Mahmud Foundation