Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Israel’s decision to seize video equipment from AP journalists last week may have been swiftly reversed but the overall direction of travel for media freedom in Israel is negative.

Journalists inside Gaza are of course paying the highest price (yesterday preliminary investigations by CPJ showed at least 107 journalists and media workers were among the more than 37,000 killed since the Israel-Gaza war began) and it feels odd to speak of equipment seizures when so many of those covering the war in the Strip have paid with their lives. But this is not to compare, merely to illuminate.

The past few days have provided ample evidence of what many within Israel have long feared – that the offensive in Gaza is not being reported on fully in Israel itself. On Tuesday a video went viral of an Israeli woman responding with outrage at the wide gulf between news on Sunday’s bombing of a refugee camp in Rafah within Israeli media compared to major international news outlets. Yesterday, in an interview with Canadian broadcaster CBC, press freedom director for the Union of Journalists in Israel, Anat Saragusti, spoke more broadly of the reporting discrepancies since 7 October:

“The world sees a completely different war from the Israeli audience. This is very disturbing.”

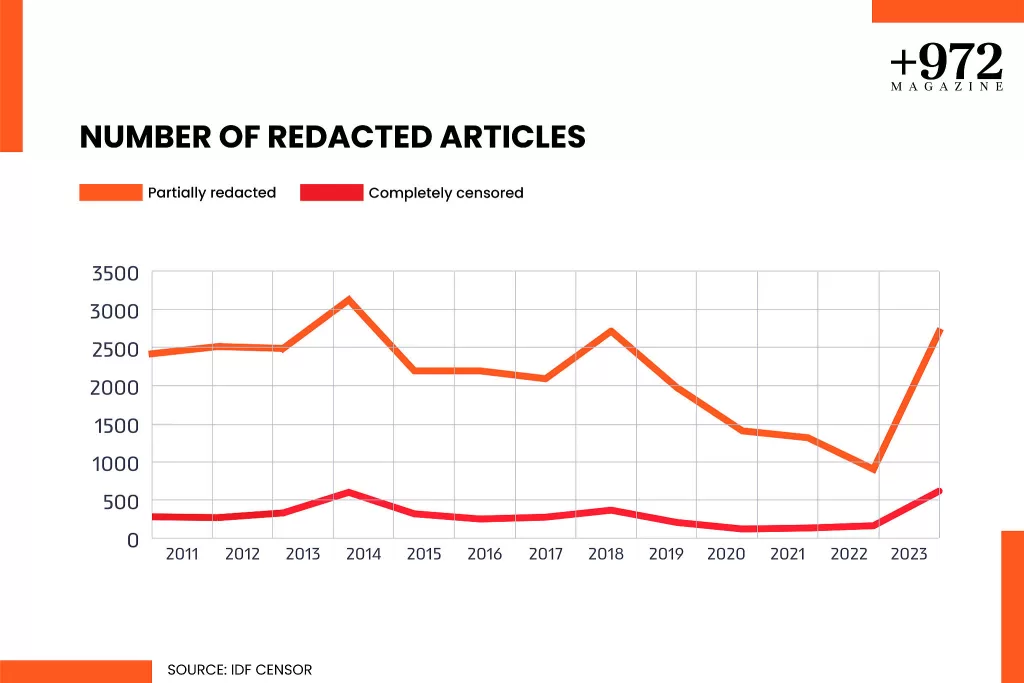

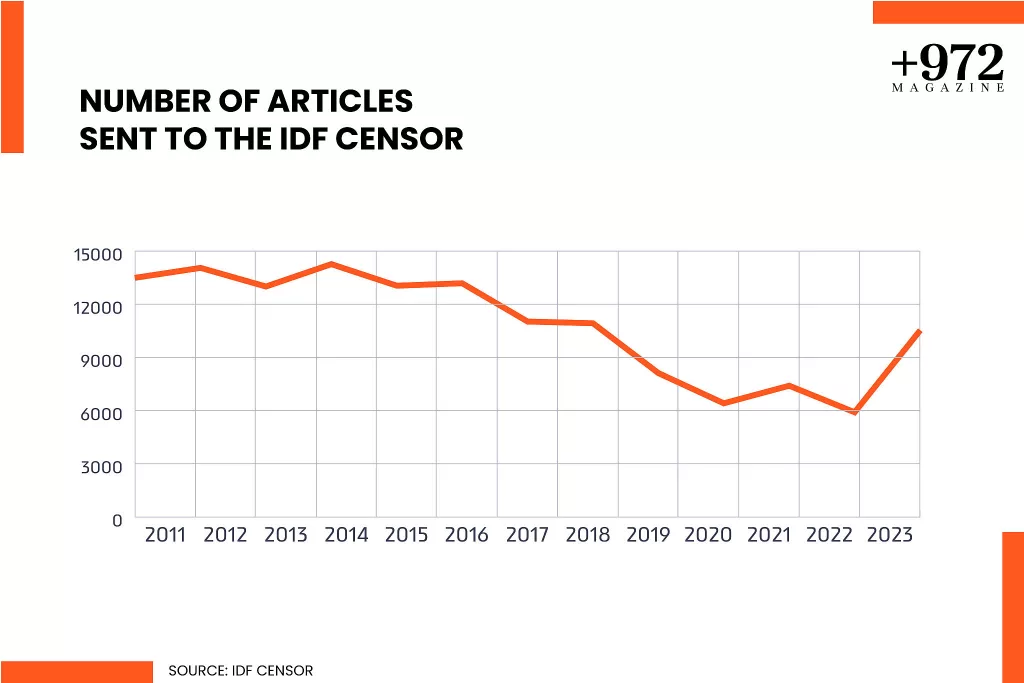

Saragusti added that part of this is because the population is still processing the horrors of 7 October and with that comes a degree of self-censorship from those within the media. The other reason, she said, is that the IDF provides much of the material that appears in Israeli media and this is subject to review by military censors. While the military has always exerted control (Israeli law requires journalists to submit any article dealing with “security issues” to the military censor for review prior to publication), this pressure has intensified since the war, as the magazine +972 showed. Since 2011 +972 have released an annual report looking at the scale of bans by the military censor. In their latest report, released last week and published on our site with permission, they highlighted how in 2023 more than 600 articles by Israeli media outlets were barred, which was the most since their tracking began.

In a visually arresting move, Israeli paper Haaretz published an article on Wednesday with blacked out words and sentences. Highlighting such redactions is incidentally against the law and will no doubt add to the government’s wrath at Haaretz (late last year they threatened the left-leaning outlet with sanctions over their Gaza war coverage).

The government’s attempts to control the media landscape was already a problem prior to 7 October. Benjamin Netanyahu is known for his fractious relationship with the press and has made some very personal attacks throughout his career, such as this one from 2016, while Shlomo Kahri, the current communications minister, last year expressed a desire to shut down the country’s public broadcaster Kan. This week it was also revealed by Haaretz that two years ago investigative reporter Gur Megiddo was blocked from reporting on how then chief of Mossad had allegedly threatened then ICC prosecutor (the story finally saw daylight on Tuesday). Megiddo said he’d been summoned to meet two officials and threatened. It was “explained that if I published the story I would suffer the consequences and get to know the interrogation rooms of the Israeli security authorities from the inside,” said Megiddo.

Switching to the present, it feels unconscionable that Israelis, for whom the war is a lived reality not just a news story, are being served a light version of its conduct.

In the case of AP, their equipment was confiscated on the premise that it violated a new media law, passed by Israeli parliament in April, which allows the state to shut down foreign media outlets it deems a security threat. It was under this law that Israel also raided and closed Al Jazeera’s offices earlier this month and banned the company’s websites and broadcasts in the country.

Countries have a habit of passing censorious legislation in wartime, the justification being that some media control is important to protect the military. The issue is that such legislation is typically vague, open to abuse by those in power, and doesn’t always come with an expiry date to protect peacetime rights.

“A country like Israel, used to living through intense periods of crisis, is particularly vulnerable to calls for legislation that claims to protect national security by limiting free expression. Populist politicians are often happy to exploit the “rally around the flag” effect,” Daniella Peled, managing editor at the Institute for War and Peace Reporting, told Index.

We voiced our concerns here in terms of Ukraine, which passed a media law within the first year of Russia’s full-scale invasion with very broad implications, and we have concerns with Israel too. But as these examples show, our concerns are far wider than just one law and one incidence of confiscated equipment.

The following article was first published by +972 Magazine, an independent, online, nonprofit magazine run by a group of Palestinian and Israeli journalists. Index on Censorship has reported on media freedom on both sides of the conflict since the 7 October attacks.

In 2023, the Israeli military censor barred the publication of 613 articles by media outlets in Israel, setting a new record for the period since +972 Magazine began collecting data in 2011. The censor also redacted parts of a further 2,703 articles, representing the highest figure since 2014. In all, the military prevented information from being made public an average of nine times a day.

This censorship data was provided by the military censor in response to a freedom of information request submitted by +972 Magazine and the Movement for Freedom of Information in Israel.

Israeli law requires all journalists working inside Israel or for an Israeli publication to submit any article dealing with “security issues” to the military censor for review prior to publication, in line with the “emergency regulations” enacted following Israel’s founding, and which remain in place. These regulations allow the censor to fully or partially redact articles submitted to it, as well as those already published without its review. No other self-proclaimed “Western democracy” operates a similar institution.

To prevent arbitrary or political interference, the High Court ruled in 1989 that the censor is only permitted to intervene when there is a “near certainty that real damage will be caused to the security of the state” by an article’s publication. Nonetheless, the censor’s definition of “security issues” is very broad, detailed across six densely-filled pages of sub-topics concerning the army, intelligence agencies, arms deals, administrative detainees, aspects of Israel’s foreign affairs, and more. Early on in the war, the censor distributed more specific guidance regarding which kinds of news items must be submitted for review before publication, as revealed by The Intercept.

Submissions to the censor are made at the discretion of a publication’s editors, and media outlets are prohibited from revealing the censor’s interference — by marking where an article has been redacted, for instance — which leaves most of its activity in the shadows. The censor has the authority to indict journalists and fine, suspend, shut down, or even file criminal charges against media organizations. There are no known cases of such activity in recent years, however, and our request to the censor to specify its indictments filed in the past year was not answered.

For more background on the Israeli military censor and +972’s stance toward it, you can read the letter we published to our readers in 2016.

“Information pertaining to censorship is of particularly high importance, especially in times of emergency,” attorney Or Sadan of the Movement for Freedom of Information told +972. “During the war, we have [witnessed] the large gaps between Israeli and international media outlets, as well as between the traditional media and social media. Although it is obvious that there is information that cannot be disclosed to the public in times of emergency, it is appropriate for the public to be aware of the scope of information hidden from it.

“The significance of such censorship is clear: there is a great deal of information that journalists have seen fit to publish, recognizing its importance to the public, that the censor chose not to allow,” Sadan continued. “We hope and believe that the exposure of these numbers, year after year, will create some deterrence against the unchecked use of this tool.”

Although the censor refused our request to provide a breakdown of its censorship figures by month, media outlet, and grounds for interference, it is clear that the reason for last year’s spike is the Hamas-led October 7 attack and the ensuing Israeli bombardment of Gaza. The only year for which there was a comparable level of silencing was 2014, when Israel launched what was then its largest assault on the Strip; that year, the censor intervened in more articles (3,122) but disqualified slightly fewer (597) than in 2023.

Last year, the censor’s representatives also made in-person visits to news studios, as has previously occurred during periods in which the government has declared a state of emergency, and continued monitoring the media and social networks for censorship violations. The censor declined to detail the extent of its involvement in television production and the number of retroactive interventions it made in regard to previously published news articles.

We do know, however, thanks to information revealed by The Seventh Eye, that despite the Israeli media’s proactive compliance — the number of submissions to the censor nearly doubled last year to 10,527 — the censor identified an additional 3,415 news items containing information that should have been submitted for review, and 414 that were published in violation of its orders.

Even before the war, the Israeli government had advanced a series of measures to undermine media independence. This led to Israel dropping 11 places in the 2023 annual World Press Freedom Index, followed by an additional four places in 2024 (it now sits in 101st place out of 180).

Since October, press freedom in Israel has further deteriorated, and the censor has found itself in the crosshairs of political battles. According to reports by Israel’s public broadcaster, Kan, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu pushed for a new law that would force the censor to ban news items more widely, and even suggested that journalists who publish reports on the security cabinet without the approval of the censor should be arrested. The chief military censor, Major General Kobi Mandelblit, also claimed that Netanyahu had pressured him to expand media censorship, even in cases that lacked any security justification.

In other cases, the Israeli government’s crackdown on media has skirted the censor and its activities entirely. Back in November, Communications Minister Shlomo Karhi banned Al-Mayadeen from being broadcast on Israeli TV, and in April, the Knesset passed a law to ban the activities of foreign media outlets at the recommendation of security agencies. The government implemented the law earlier this month when the cabinet unanimously voted to shut down Al Jazeera in Israel, and the ban will now reportedly also be extended to the West Bank. The state claims that the Qatari channel poses a danger to state security and collaborates with Hamas, which the channel rejects.

The decision will not affect Al Jazeera’s operations outside of Israel, nor will it prevent interviews with Israelis via Zoom (full disclosure: this writer sometimes interviews with Al Jazeera via Zoom), and Israelis can still access the channel via VPN and satellite dishes. But Al Jazeera journalists will no longer be able to report from inside Israel, which will reduce the channel’s ability to highlight Israeli voices in its coverage.

The Association for Civil Rights in Israel and Al Jazeera petitioned the High Court against the decision, and the Journalists’ Union also issued a statement against the government’s decision (full disclosure: this writer is a member of the union’s board).

Despite these various attacks on the media, the most significant threats posed by the Israeli government and military, and especially during the war, are those faced by Palestinians journalists. Figures for the number of Palestinian journalists in Gaza killed by Israeli attacks since October 7 range from 100 (according to the Committee for the Protection of Journalists) to more than 130 (according to the Palestinian Journalists Syndicate). Four Israeli journalists were killed in the October 7 attacks.

The heightened government interference in Israeli media does not absolve the mainstream press of its failure to report on the army’s campaign of destruction in Gaza. The military censor does not prevent Israeli publications from describing the war’s consequences for Palestinian civilians in Gaza, or from featuring the work of Palestinian reporters inside the Strip. The choice to deny the Israeli public the images, voices, and stories of hundreds of thousands of bereaved families, orphans, wounded, homeless, and starving people is one that Israeli journalists make themselves.

This article was previously published by +972 here.

The Spring 2024 issue of Index looks at how authoritarian states are bypassing borders in order to clamp down on dissidents who have fled their home state. In this issue we investigate the forms that transnational repression can take, as well as highlighting examples of those who have been harassed, threatened or silenced by the long arm of the state.

The writers in this issue offer a range of perspectives from countries all over the world, with stories from Turkey to Eritrea to India providing a global view of how states operate when it comes to suppressing dissidents abroad. These experiences serve as a warning that borders no longer come with a guarantee of safety for those targeted by oppressive regimes.

Border control, by Jemimah Steinfeld: There's no safe place for the world's dissidents. World leaders need to act.

The Index, by Mark Frary: A glimpse at the world of free expression, featuring Indian elections, Predator spyware and a Bahraini hunger strike.

Just passing through, by Eduardo Halfon: A guided tour through Guatemala's crime traps.

Exporting the American playbook, by Amy Fallon: The culture wars are finding new ground in Canada, where the freedom to read is the latest battle.

The couple and the king, by Clemence Manyukwe: Tanele Maseko saw her activist husband killed in front of her eyes, but it has not stopped her fight for democracy.

Obrador's parting gift, by Chris Havler-Barrett: Journalists are free to report in Mexico, as long as it's what the president wants to hear.

Silencing the faithful, by Simone Dias Marques: Brazil's religious minorities are under attack.

The anti-abortion roadshow, by Rebecca L Root: The USA's most controversial new export could be a campaign against reproductive rights.

The woman taking on the trolls, by Daisy Ruddock: Tackling disinformation has left Marianna Spring a victim of trolling, even by Elon Musk.

Broken news, by Mehran Firdous: The founder of The Kashmir Walla reels from his time in prison and the banning of his news outlet.

Who can we trust?, by Kimberley Brown: Organised crime and corruption have turned once peaceful Ecuador into a reporter's nightmare.

The cost of being green, by Thien Viet: Vietnam's environmental activists are mysteriously all being locked up on tax charges.

Who is the real enemy?, by Raphael Rashid: Where North Korea is concerned, poetry can go too far - according to South Korea.

The law, when it suits him, by JP O'Malley: Donald Trump could be making prison cells great again.

Nowhere is safe, by Alexander Dukalskis: Introducing the new and improved ways that autocracies silence their overseas critics.

Welcome to the dictator's playground, by Kaya Genç: When it comes to safeguarding immigrant dissidents, Turkey has a bad reputation.

The overseas repressors who are evading the spotlight, by Emily Couch: It's not all Russia, China and Saudi Arabia. Central Asian governments are reaching across borders too.

Everything everywhere all at once, by Daisy Ruddock: It's both quantity and quality when it comes to how states attack dissent abroad.

A fatal game of international hide and seek, by Danson Kahyana: After leaving Eritrea, one writer lives in constants fear of being kidnapped or killed.

Our principles are not for sale, by Jirapreeya Saeboo: The Thai student publisher who told China to keep their cash bribe.

Refused a passport, by Sally Gimson: A lesson from Belarus in how to obstruct your critics.

Be nice, or you're not coming in, by Salil Tripathi: Is the murder of a Sikh activist in Canada the latest in India's cross-border control.

An agency for those denied agency, by Amy Fallon: The Sikh Press Association's members are no strangers to receiving death threats.

Always looking behind, by Zhou Fengsuo and Nathan Law: If you're a Tiananmen protest leader or the face of Hong Kong's democracy movement, China is always watching.

Putting Interpol on notice, by Tommy Greene: For dissidents who find themselves on Red Notice, it's all about location, location, location

Living in Russia's shadow, by Irina Babloyan, Andrei Soldatov and Kirill Martynov: Three Russian journalists in exile outline why paranoia around their safety is justified.

Solidarity, Assange-style, by Martin Bright: Our editor-at-large on his own experience working with Assange.

Challenging words, by Emma Briant: An academic on what to do around the weaponisation of words.

Good, bad and everything that's in between, by Ruth Anderson: New threats to free speech call for new approaches.

Ukraine's disappearing ink, by Victoria Amelina and Stephen Komarnyckyj: One of several Ukrainian writers killed in Russia's war, Amelina's words live on.

One-way ticket to freedom?, by Ghanem Al Masarir and Jemimah Steinfeld: A dissident has the last laugh on Saudi, when we publish his skit.

The show must go on, by Katie Dancey-Downs, Yahya Marei and Bahaa Eldin Ibdah: In the midst of war Palestine's Freedom Theatre still deliver cultural resistance, some of which is published here.

Fight for life - and language, by William Yang: Uyghur linguists are doing everything they can to keep their culture alive.

Freedom is very fragile, by Mark Frary and Oleksandra Matviichuk: The winner of the 2022 Nobel Peace Prize on looking beyond the Nuremberg Trials lens.

Yes! Yes Sir! Life is normal

A labourer’s annual wage is worth a dinner abroad

Yes! Of course, Sir! Life is normal

We don’t dare say otherwise, in case we get in trouble

These are the opening lines of Toomaj Salehi's song Normal. Salehi did dare to say otherwise though and for that he did get in trouble. On Wednesday an Iranian revolutionary court sentenced him to death. The charge was “corruption on earth”. The only thing corrupt is Iran's regime.

For those unfamiliar with Salehi, he is a well-known Iranian hip-hop artist whose lyrics are infused with references to the human rights situation in Iran. He was an outspoken supporter of the Woman, Life, Freedom movement. Last year, Index awarded Salehi a Freedom of Expression award in the Arts category. Salehi donated his cash prize to victims of recent floods in Iran.

Because of his advocacy Salehi has faced continuous judicial harassment, including arrest and imprisonment. He has been in and out of prison since 2021. A moment of respite came in November 2023 when Iran’s Supreme Court struck down Salehi’s six-year prison sentence. The respite was short-lived. Just days after he was released from prison Salehi was rearrested upon uploading a video to YouTube documenting his treatment while in detention.

On 18 April 2024, Branch 1 of Isfahan’s Revolutionary Court held a new trial for Salehi where the court ultimately convicted Salehi and sentenced him to death. His lawyer alleged that the ruling had significant legal errors, including contradicting the Supreme Court verdict. He said that they will appeal the verdict. They only have 20 days.

Index has been in close contact with his family, as well as lawyers and other organisations who work in our field. We are shocked by the barbarity of this decision (please read our CEO Ruth Anderson's article on what he means to us more personally here), as well as heartened by how the international community has pulled together. If you are on social media and have not yet engaged with his case, we have a small favour to ask - do please post about Salehi and use the hashtag #FreeToomaj. Making noise might not change the outcome of the case but we know that solidarity can have a huge impact on the emotional wellbeing of dissidents and their families.

Salehi’s case is top of the Index priority list. Still, we have been keeping a close eye on the USA, where academic freedom, free assembly and broader First Amendment rights are being put to the test. While we have seen instances of hate speech directed towards Jewish students - vile and unjustifiable - the overall picture being painted is one of police overreach and brutality. There are too many disturbing scenes by now but let me highlight one - a CNN video of Professor Caroline Fohlin from Emory University in Atlanta being hurled to the ground and handcuffed. She had simply asked the police "What are you doing?" after she came across the violent arrest of a protester on campus.

There are immediate concerns for free speech here. Beyond these are two longer term ones. Firstly that this is part of a broader pattern of less tolerance towards protest across the world. We’ve seen it in the UK in the form of legislation restricting where and how people can protest, which has also led to an overzealous police force who arrest campaigners before their protests even start. Secondly that this will provide perfect justification for Trump, should he be re-elected, to further crack down on rights. "Look", he’ll say, "Biden's administration did it too".

We’ve read a lot of good, thoughtful articles this week about the protests, such as this from Slate talking to Columbia students about the situation on the ground, this from Robert Reich on the free speech implications (he argues universities should actively encourage debate and disagreement) and this from Sam Kahn on what it feels like to be Jewish in the USA right now (he takes issue with what he terms a "nothing-to-see-here je ne sais quoi" approach to the protests). We also had an NYU professor, Susie Linfield, commenting late last year here. Do take a read. It feels slightly like wading through treacle right now - it's easy to get stuck on one argument and then stuck on a totally different one. So we should take a step back and that step back for me came from the Gazan-American Ahmed Fouad Alkhatib when he commented on what was happening at the University of Texas Austin:

“Regardless of what you think of pro-Palestine protesters, attacking students (and a cameraman) during a peaceful assembly is shameful and wrong. This will inspire even more protests and further inflame a really difficult and an impossible situation. Absent acts of violence, harassment, or destruction of property, students have a right to freedom of expression. We cannot lose sight of that.”

Whether in the USA or Iran we stand by peaceful protesters and we will always call out those who seek to silence them.