19 Aug 2013 | Digital Freedom, France, News and features, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture

(Photo illustration: Shutterstock)

Freedom of expression is generally protected in France, although is limited by strict defamation and privacy laws. Several laws have passed since 1972 that have further restricted this fundamental right.

In addition to strict privacy laws, France’s libel laws make it easy to sue for defamation. Losing a libel case against a public official carries a higher fine (€45,000) than libel against a private individual (€12,000), which chills public interest criticism of politicians and government officials.

France has some of the toughest hate speech laws in the EU. The number of legal actions for hate speech have multiplied after the 1881 Law on Press Freedom was amended to introduce the offence of inciting racial hatred, discrimination, violence, or contesting the existence of crimes against humanity, which has been very broadly interpreted as the right not to be offended or criticised. Some civil society groups have even managed to force the cancellation of public debates in order to prevent potentially libellous or racist remarks[1].

Since 2004, wearing signs or clothing that overtly manifest a religious affiliation is prohibited in schools[2]. In 2011, France implemented a ban on the niqab or face veil in public places. In September 2011, Paris passed a ban on Muslim street prayers, restricting the right to religious expression.

Media Freedom

France’s media is generally regarded as free and represents a wide range of political opinion. Still, it faces economic, social and political challenges in particular from the security services and from the country’s stringent privacy laws.

Since 2009, France’s president has appointed the executives in charge of its public broadcasting outlets. This controversial measure was heavily criticised since, as it was seen as politicising public broadcasting and put into question its executives’ independence President Francois Hollande has promised to relinquish this privilege. He has also promised to review policies related to public broadcasting funding and management.

Another challenge for media freedom in France has been state intervention to prevent the exposure of corruption. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, former President Nicolas Sarkozy used the security services to identify the sources of leaks around the 2010 Liliane Bettencourt affair. In addition to accessing the phone records of a Le Monde journalist, journalists from major newspapers were also investigated. Not only did the chief of intelligence violate the confidentiality of journalistic sources, but he questioned the journalist’s right to investigate public corruption.

France’s privacy law is often described as the toughest in the world. This is because the publication of private details of someone’s life without their consent is a punishable offence, with limited public interest defences available. Privacy is safeguarded not only by civil law provisions but also by the existence of specific criminal offences which indirectly promote the withholding of information and self-censorship and limit the exposure of political corruption.

Digital Freedom

About 79.6% of the French population is online. Yet, digital freedom is curtailed by anti-terror laws, increased online surveillance and libel laws.

Online surveillance has been extended as a result of a 2011 anti-terror law[3] and Hadopi 2 (the law “promoting the distribution and protection of creative works on the Internet”) which is supposed to reduce illegal file downloading. Hadopi 2 makes it possible for content creators to pay private-sector companies to conduct online surveillance and filtering, creating a precedent for the privatisation of censorship. Another 2011 law requires internet service providers to hand over passwords to authorities if requested. Concerns have been raised over new legislation enabling the authorities to impose filters on the web without a court order and on the impact of new anti-terror laws that allows for the blocking of websites.

The French Press Freedom Law of 1881 – which guarantees freedom of expression for the press – has been amended so that it applies to online publication. It aims to extend the protections for press freedom online but also allows people to take legal action for libellous or hate speech online, including on blogs posts, tweets and Facebook comments. In October 2012, a French court ruled that Twitter should provide the identities of users who tweeted jokes deemed to be offensive to Muslims and Jews. This was after the Union of French Jewish Students threatened to bring the social media giant to court. During the course of the case, French Minister of Justice Christiane Taubira said that it is a punishable offence to make racist or anti-Semitic comments online. There is pressure to reframe the 1881 Law on Press Freedom, which many consider “no longer adapted to new technologies”.

Artistic Freedom

France has a vibrant art scene but one restricted in various ways by hate speech laws and by interference from public authorities.

Racial hatred and other discriminatory and violent language in artistic work with a potentially large audience is criminalised as a “public expression offence”. Many artists have been brought to Court for this offence which lies mainly in Article 24 of the 1881 Law on Press Freedom.[4] This offence is particularly serious since it is punishable by five years’ imprisonment and a €45,000 fine. Government officials, civil society groups, and individuals have repeatedly sued artists for defamation and incitement to violence.

The Code of Intellectual Property protects artistic works whatever their content and merit, and protects their authors. However, artistic freedom of expression can be restricted by various authorities – Ministry of Culture, Superior Council of Audio-visual (Conseil supérieur de l’audiovisuel, CSA) – whose decisions may limit not only the dissemination of works, but also their production (TV, films).The CSA for example, whose members are political appointments, is regularly exposed to pressure from the public, elected officials, or political authorities to censor artistic works.

[1] Loi n° 2004-228 du 15 mars 2004 encadrant, en application du principe de laïcité, le port de signes ou de tenues manifestant une appartenance religieuse dans les écoles, collèges et lycées publics [Law of 15 March 2004, forbidding signs and clothing showing religious affiliation such as headscarves, Jewish skullcaps and oversized Christian crosses in public primary, secondary and higher education]

[2] Loi n° 2011-267 du 14 mars 2011 d’orientation et de programmation pour la performance de la sécurité intérieure [Law of 14 March 2011 on guidance and planning for the performance of domestic security]

[3] Décret n° 2011-219 du 25 février 2011 relatif à la conservation et à la communication des données permettant d’identifier toute personne ayant contribué à la création d’un contenu en ligne [Decree of 25 February 2011 on the conservation and communication of data to identify any person who contributed to the creation of online content]

[4] Loi du 29 juillet 1881 sur la liberté de la presse, Version consolidée au 23 décembre 2012 [Law of 29 July 1881 on Press Freedom]

This article was originally published on 19 Aug, 2013 at indexoncensorship.org. Index on Censorship: The voice of free expression

15 Aug 2013 | Canada, Digital Freedom, Index Reports, News and features, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture

(Photo illustration: Shutterstock)

Despite having a generally positive free expression record, Canada has, in recent years, taken some regressive steps, driven by court decisions that weakened confidentiality for journalists’ sources, obstructions to reporting during Quebec’s student protests and the introduction of a bill, which was later withdrawn, but would have allowed the government to monitor Canadians in real-time without the need for a warrant.

Conservative Prime Minister Steven Harper’s government has been criticised by activists for its tightening of access to information and slow response time to requests. Harper is accused of banning government-funded scientists from speaking to reporters about climate research. The country’s 30-year-old Access to Information Act (ATIA) is also highlighted as an obstacle.

Canada’s Provincial governments exercise strong influence on the rights of the media and individuals. During the so-called “Maple Spring” in 2012 Quebec passed an emergency law aimed at stifling student protests against tuition increases.

Media Freedom

Cases challenging source confidentiality and various proposed bills have given free expression campaigners pause about the state of media freedom.

Currently, there are concerns about a move to foster tighter regulation of state-owned Crown corporations which would have potentially chilling effects on the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation and Radio Canada. Bill C-60 “gives the Treasury Board the right to approve Crown Corporations’ negotiating mandates, have a Board employee present at the negotiations between unions and management, and to approve the new contracts at the end of the process.“ The worry is that C-60 would lead to a deterioration of the arms-length relationship between the government and CBC, the country’s independent public broadcaster. A group of free expression organisations are calling for the CBC to be exempt from the Bill.

Canadian Journalists for Free Expression’s 2012-2013 report outlines a systemic failure of the Canadian government to respond to requests for information, particularly around climate change research. The report details that some government-funded scientists must seek permission from the country’s Privy Council before speaking to the press – even in cases where the research is already published. As CJFE points out, delayed information often leads to journalism denied. The group singles out the Department of Fisheries and Oceans for seeking to muzzle its scientists.

Two 2010 court cases have dealt with journalistic privilege head on. While Canada’s Supreme Court Justices have stopped short of offering blanket confidentiality, they have stressed that compelling journalists to reveal sources should be extraordinary and not the rule, recognizing that investigative reporting plays an important role in society. Instead, tests should be applied on a case by case basis. In addition, the court ruled that journalists have the right to publish confidential material from a source — even when the source has no right to divulge the information or has obtained it by illegal means.

Digital Freedom

With widespread access and improving infrastructure for native groups in the country’s far north, Canada’s digital freedom environment can be seen as healthy. However, government efforts to monitor online activity in the name of security, a growing concentration of bandwidth ownership and outdated laws on privacy have troubling implications.

Digital freedom has risen to the forefront of concerns in Canada. Introduced in 2012, Bill C-30 would have allowed real-time surveillance of Canadians. The law was attacked as an unprecedented intrusion in the online life of Canadians and would have forced internet providers to install costly systems to track web usage. After being recast as a proposal meant to protect children from exploitation, the bill was eventually withdrawn in February 2013.

In February 2013, Canada’s government shelved Bill C-30, the Lawful Access Bill, in the face of widespread condemnation. Among other things, the proposed law would have allowed warrantless online surveillance. While the government presented the law as a child protection measure, opponents focused on the population-wide intrusion into the online lives of all Canadians. The bill would have also forced communications companies to undertake a costly implementation of technologies to monitor and record internet traffic. The abandonment of the bill was hailed as a victory by free expression advocates.

Canada’s Canada’s Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act, which is an outdated 2001 law on consumer privacy is also a threat to digital freedom. The country’s top official on privacy, Jennifer Stoddart, has asked the government to give her the power to fine companies found to be in breach of rules. At present, companies are not required to disclose personal data breaches. Bill C-12, would have amended the law, but failed to move forward after its second reading in the Canadian Parliament. However, that proposal also drew criticism from open internet activists because it would give police access to user information without judicial oversight or notification to the affected party.

Artistic freedom

Artistic freedom in Canada is protected by The Constitution Act of 1982, which contains the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Artistic endeavours often encounter difficulty in Canada due to a lack of available stable funding from the private sector. This can result in a reliance on federal or provincial funding, which means that governments can try to rein in artistic work they feel is controversial by threatening to withdraw funding.

In 2010, the government pulled funding from the Toronto theatre and music festival SummerWorks, after it displayed a play the government felt glorified terrorism. SummerWorks efforts were seriously damaged as a result — government funding accounted for 20 percent of the festival’s finances. Funding was later restored in 2012.

The Ontario Film Review Board, a governmental body once known as the Board of Censors when established in 1911, answers to the Minister of Consumer Services. Its activities are supported by the Film Classification Act, 2005.

In April 2007, after much dispute amongst the artistic community in Canada, MPs removed the artistic merit defence from Canada’s Criminal Code. The defence was originally granted by the Supreme Court of Canada in 2004, but Conservative MP Pierre Lemieux attempted once again to table the Private Member’s Bill C-430, which would remove artistic defence and replace it with public good.

This article was originally published on 16 Aug 2013 at indexoncensorship.org. Index on Censorship: The voice of free expression

12 Aug 2013 | Asia and Pacific, China, News and features, Politics and Society, Taiwan

Activists and civic groups march in Taipei in protest against the Want Want China Times Group’s planned acquisition of China Network Systems’s cable TV services in Sept 2012.

(Photo: Craig Ferguson / Demotix)

The connections between China and Taiwanese media owners has given rise to concerns, along with some evidence, that the industry is under growing pressure to curb reporting on topics detrimental to Chinese interests and cross-strait ties.

The capital, Taipei, erupted in protests when it became known that Tsai Eng-ming, a pro-Beijing businessman, attempted to wrest control of Taiwan’s largest newspaper, the Apple Daily, earlier this year. The attempt failed amid popular outrage. But conversations with several journalists suggest that Beijing continues to exert a quieter influence – involving self-censorship and lucrative business interests – in attempt to avoid further scrutiny.

This is perhaps most prominent at the China Times Group, a Taiwanese media conglomerate that Tsai purchased in 2008. Estimated to be worth up to US$10.6 billion, the snack manufacturer has since led its subsidiaries to become more China-friendly, accepting payment from Beijing in return for camouflaged advertising and one-sided reporting. His flagship daily, the China Times, has been fined multiple times by Taiwan’s media regulators for masquerading advertising as reporting.

“It happens far more frequently than most people realize,” said Lin Chao-yi, the former head of the Association of Taiwan Journalists, that uncovered one such example last year. After receiving a copy of a schedule detailing how a visit from a ranking Chinese official was to be covered, including pre-defined topics and article lengths, Lin then impersonated a China Times employee to ask the delegation how the paper was going to be compensated.

Caught on tape, the Chinese press officer replied that the payment would be wired to a China Times Group subsidiary in Beijing. But far from discouraging such deals from taking place again, Lin said that his report “just made them more careful.” Indeed, accepting Chinese money is not only lucrative business, but also allows the paper to stay on Beijing’s good graces – guaranteeing access from behind China’s Great Firewall – according to sources familiar with the relationship.

The China Times Group’s cosy relationship with Beijing has led some journalists working under its banner to become more aware of what might, and might not, be publishable. Speaking on the condition of anonymity, one China Times reporter said that, there is an “unspoken understanding” of what articles or reports might contradict the paper’s political viewpoint, including, for example, pieces critical of either Beijing or Taiwan’s China-friendly president, Ma Ying-jeou.

“In these cases, we might choose to just drop the subject, instead of choosing to pursue it further,” the reporter said, in words reminiscent of the self-censorship taking place elsewhere in the Chinese-speaking region.

But far from taking place only at the China Times Group, self-censorship is also seen as a necessity by other media groups keen on maintaining access to the Chinese market. Much of this has to do with Taiwan’s highly profitable entertainment industry that feeds thousands of hours of programming each year into local Chinese television channels. Produced by the same media groups that also run cable news stations, coverage of some politically sensitive topics, such as the Dalai Lama or the Falungong movement, are toned down to avoid antagonizing Beijing.

“China uses its vast market as a bargaining chip,” said Cheryl Lai, the former editor-in-chief of the state run Central News Agency, adding that most of this takes place secretly and away from public scrutiny. “They know that most of these media companies are in it for the money. All they have to do is threaten to cut it off.”

The trend towards greater Chinese influence in the media is reflective of the realization that its political objectives of unifying Taiwan, which it claims to be a breakaway province, can be achieved cheaper and more effectively through propaganda, rather than force. Instead of “spilling blood on Taiwan,” an old rallying call for conquering the island by force if necessary, Beijing has deemed it easier to “spill money on Taiwan,” said Lai, who has been writing on China’s growing political sway on the island.

The same trend can be seen elsewhere where China holds political interests, such as Hong Kong, where a large number of publications are ostensibly under its influence. The South China Morning Post, for example, has reportedly been hit by allegations of self-censorship after the appointment of new Editor-in-Chief Wang Xiangwei, a member of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Congress, a Chinese government body.

In Taiwan, even as most media interests are controlled by large corporations, some with extensive business ties to China, there is, however also a realization that hard-fought press freedoms must be protected. More than 100,000 protestors, including students and reporters, rallied in defence of the Apple Daily during the failed purchase in January this year, with some groups vowing to raise the equivalent funds if it meant protecting the paper’s journalistic integrity.

All this is reason why Beijing is likely to continue and incubate its media influence behind the scenes, at least for now.

8 Aug 2013 | France, News and features, Politics and Society

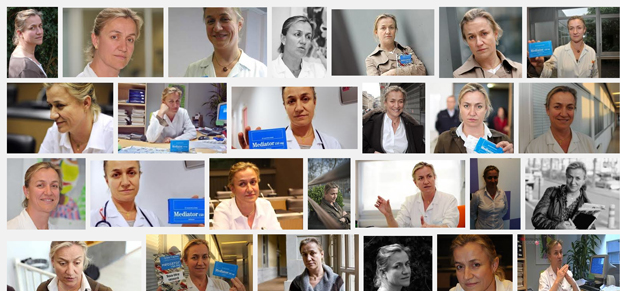

Irène Frachon is a French pneumologist who discovered that an antidiabetic drug frequently prescribed for weight loss called Mediator was causing severe heart damage.

The French term “lanceur d’alerte” [literally: “alarm raiser”], which translates as “whistleblower”, was coined by two French sociologists in the 90’s and popularised by scientific André Cicolella, a whistleblower who was fired in 1994 from l’Institut national de recherche et de sécurité [the National institute for research and security] for having blown the whistle on the dangers of glycol ethers.

While the history of whistleblowing in the United States is closely associated with the case of Daniel Ellsberg, who leaked the Pentagon Papers to The New York Times in 1971, exposing US government lies and helping to end the Vietnam war, whistleblowing in France was first associated with cases of scientists who raised the alarm over a health or an environmental risk.

In England, the awareness that whistleblowers needed protection grew in the early 1990s, after a series of accidents (among which the shipwreck of the MS Herald of Free Enterprise ferry, in 1987, which caused 193 deaths) when it appeared that the tragedies could have been prevented if employees had been able to voice their concerns without fear of losing their job. The Public Interest Disclosure Act, passed in 1998, is one of the most complete legal frameworks protecting whistleblowers. It still is a reference.

France had no shortage of national health scandals in the 1990s, from the case of HIV-contaminated blood to the case of growth hormone. But no legislation followed. For a long time, whistleblowers were at the center of a confusion: their action was seen as reminiscent of the institutionalised denunciations that took place under the Vichy regime when France was under Nazi occupation. In fact, no later than this year, some conservative MPs managed to defeat an amendment on whistleblowers’ protection by raising the spectre of Vichy.

For Marie Meyer, Expert of Ethical Alerts at Transparency International, an anti-corruption NGO, this confusion makes little sense: “Whistleblowing is heroic, snitching cowardly”, she says.

“In France, the turning point was definitely the Mediator case, and Irène Frachon,” Meyer adds, referring to the case of a French pneumologist who discovered that an antidiabetic drug frequently prescribed for weight loss called Mediator was causing severe heart damage. In 2010, Frachon published a book – Mediator, 150mg, Combien de morts ? [“Mediator, 150mg, How Many Deaths?”] – where she recounted her long fight for the drug to be banned. Servier, the pharmaceutical company which produced the drug, managed to censor the title of the book and get it removed from the shelves two days after publication, before the judgement was overturned. Frachon has been essential in uncovering a scandal which is believed to have caused between 500 and 2000 deaths. With scientist André Cicolella, she has become one of the better-known French whistleblowers.

“What is striking is that people knew, whether in the case of PIP breast implants or of Mediator”, says Meyer. “You had doctors who knew, employees who remained silent, because they were scared of losing their job.”

This year, the efforts of various NGOs led by ex whistleblowers were finally met with results. Last January, France adopted a law (first proposed to the Senate by the Green Party) protecting whistleblowers for matters pertaining to health and environmental issues. The Cahuzac scandal, which fully broke in February and March, prompting the minister of budget to resign over Mediapart’s allegations that he had a secret offshore account, was instrumental in raising awareness and created the political will to protect whistleblowers.

For Meyer, France’s failure to protect whistleblowers employed in the public service has had direct consequences on the level of corruption in the country.

“Even if a public servant came to know that something was wrong with the financial accounts of a Minister, be it Cahuzac or someone else, how could he have had the courage to say it, and risk for his career and his life to be broken?” she says.

In June, as France discovered Edward Snowden’s revelations in the press over mass surveillance programs used by the National Security Agency, it started rediscovering its own whistleblowers: André Cicolella, Irène Frachon or Philippe Pichon, who was dismissed as a police commander in 2011 after his denunciations on the way police files were updated. Banker Pierre Condamin-Gerbier, a key witness in the Cahuzac case, was recently added to the list, when he was imprisoned in Switzerland on the 5th of July, two days after having been heard by the French Parliamentary Commission on the tax evasion case.

Three new laws protecting whistleblowers’ rights should be passed in the autumn. France will still be missing an independent body carrying out investigations into claims brought up by whistleblowerss, and an organisation to support them, like British charity Public Concern at Work does in the UK.

So far, French law doesn’t plan any particular protection to individuals who blow the whistle in the press, failing to recognise that, for a whistleblower, communicating with the press can be the best way to make a concern public – guaranteeing that the message won’t be forgotten, while possibly seeking to limit the reprisal against the messenger.