11 Apr 2019 | Digital Freedom, News, United Kingdom

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

There is a tired stereotype that the British don’t “do” sex. It’s too embarrassing, too shocking to be talked about in public spaces. The cliché has long been considered outdated in the wake of the obscenity trials of the mid-1960s when works such as Lady Chatterley’s Lover were vindicated. And, so the story goes, the road has paved the way to a more permissive society.

Yet with the passage of the UK’s Digital Economy Act 2017, there could all be about to change. The act, created by the Department of Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, mandates — among other things — that all pornographic websites have strong age verification checks. Ostensibly created to safeguard children from pornography, these checks would require users to either purchase a special “porn pass” in a physical shop or submit official forms of documentation to private companies for verification.

This age verification scheme has been repeatedly delayed, most recently on 1 April 2019. However, it has not been taken off the table, with the government still working to roll out the scheme sometime in the near future. This is despite the policy having been met with criticism by many anti-censorship and privacy campaigners, who see it as setting an unhealthy risk to online anonymity, net neutrality and sexual freedom.

The law has the potential to pose a severe threat to the anonymity of people in the UK.

Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index on Censorship, explains: “This plan is riddled with problems. As David Kaye, the UN’s Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression has said, identity disclosure requirements in law allow authorities to identify people more easily, which threatens anonymous expression”.

David Kaye has long been a vocal critic of violations of net neutrality such as the UK’s “porn ban”, which can have a severe cooling effect on the public’s ability to express themselves freely.

He states that: “The internet has profound value for freedom of opinion and expression, as it magnifies the voice and multiplies the information within reach of everyone who has access to it. Within a brief period, it has become the central global public forum. As such, an open and secure internet should be counted among the leading prerequisites for the enjoyment of freedom of expression today.”

According to Kaye, any requirement for the disclosure of identity or obtain an officially recognised documentation to access pornography would allow authorities to identify people more easily, and threatens that kind of anonymous expression. Similarly, creating legally sanctioned barriers which severely restrict access to online content such as pornography would be harmful to individuals’ right to expression.

The law will be overseen by the British Board of Film Classification, the 107-year-old organisation responsible for age ratings on films, which among other things rated Watership Down — a 1978 British animated adventure-drama film complete replete with violent scenes of rabbits ripping each other’s throats out — “U” for universal, or suitable for all. However, the actual enforcement of it will be left to private “age verification” companies.

The systems currently being prepared for use after the scheme is rolled out by companies such as AgeID and AgeChecked typically require the user to provide formal, high-risk personal identification such as a passport, driver’s licence or credit card through a third party. Once sufficient identification is provided, users will be granted access to all websites that use them. Other information such as names, addresses and bank details may also be required, but no matter how well encrypted, the storing of this data comes with a risk.

Yet with AgeID — the company expected to dominate the UK age verification market — being owned by pornography giant MindGeek, this risk may only be enhanced. MindGeek is also the parent company of PornHub, YouPorn and RedTube, and may represent a strong conflict of interest.

As Jim Killock, executive director of the Open Rights Group explains: “The porn company MindGeek will become the Facebook of age verification, dominating the UK market. They would then decide what privacy risks or profiling take place for the vast majority of UK citizens.”

“The government has repeatedly refused to ensure that there is a legal duty for age verification providers to protect the privacy of web users,” Killock adds. “Age verification could lead to porn companies building databases of the UK’s porn habits, which could be vulnerable to Ashley Madison style hacks.”

The risks of these databases being hacked is a distinct possibility. The 2015 Ashley Madison data breach, in which hackers exposed the names, email addresses, phone numbers and credit card details of users of the dating site whose slogan was “Life is short. Have an affair”.

Subsequent to the breach, exposed users found themselves at risk of losing careers, broken marriages and extortion or suicide, as in the case of John Gibson, a pastor at the New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary whose suicide note mentioned the data breach.

For one vocal critic, Clarissa Smith, professor of sexual cultures at the University of Sunderland, the law seems like an ineffective attempt for the government to appear to be addressing a largely manufactured issue. She argues that the resulting law ultimately doesn’t even address the underlying problems which it claims to address.

“As is often the case with this kind of legislation, it was rolled into a portmanteau bill, and the age verification provisions were barely discussed because they’re just one aspect of the bill,” Smith said. The legislation then passed, and most people are unaware that the provisions were even there. Those that do take note are often dismissed as the cranks or perverts ‘who don’t care about children’.”

“The result is that broader problems about data security, rights to privacy and sexual freedoms are all swept away in the name of ‘doing something for the kids’,” she added. “And people ignore this kind of legislation because they presume it won’t apply to their own sex lives, or that if they don’t watch much porn they won’t be affected.”

The issue, Smith argues, is not that pornography is accessible, but that it is not talked about with young people, except to discourage them from seeking it out.

“I think there are lots of more productive ways of dealing with adult concerns about what young people are viewing online. Too often they turn straight to protection, prevention and prohibition when what could be done would be to offer education and support so that kids make the right choices for themselves.”

According to Jerry Barnett, campaigner and author of Porn Panic!: Sex and Censorship in the UK, the regulation of the porn industry is a sign of greater underlying threats to net neutrality. For Barnett, the problems with the age verification system, though still significant, pale in comparison to the government’s power to block porn websites outright if they don’t comply with the law. He says that allowing the government to block non-compliant porn sites could set a dangerous precedent for other forms of online censorship in the future.

“While the discussion has centred on the ‘age verification’ requirement, the real problem comes with the blocking system that will be used to prevent UK citizens accessing non-compliant sites,” Barnett says. “That should be the focus of civil liberties campaigners, as it can be used to block anything.”

“The burning issue is that a ‘Great Firewall of Britain’ has been quietly built using the age verification requirements as an excuse, he adds. “The blocking system, rather than the age verification system, will fundamentally change the nature of the internet.”

The Digital Economy Act permits the BBFC to block porn websites which do not comply with their regulations, as well as allowing them to impose fines of up to £250,000 upon them as an alternative.

Barnett argues that if the law had not been specifically targeted at pornography, a law such as the Digital Economy Act would have been the subject of strong public debate, such as the recent discussion surrounding Article 13, the EU’s new copyright directive. Like Smith, he suggests that such debate struggled in the face of the strong cultural stigma which surrounds sex and pornography.

“The issue requires someone who will ‘defend the indefensible’ in the media, and there aren’t many of us around,” he says. “In order to oppose censorship, you find yourself defending things — such as the right of teenagers to access sexual content — that few people are prepared to defend.”

Despite the many issues which plague the law, the vast majority of the UK population is apparently unaware of it. According to a poll conducted by YouGov published on 18 March, less than a month before the new regulations were due to be rolled out, only 24% of Britons were aware of the new law- or what it entailed.

The same study found that 67% of those surveyed supported the changes after being informed of the law — including over a quarter of those who viewed pornography most frequently.

Seemingly, even many people who in private would be hit hardest by the new measures support them due to the social stigma of being opposed to them.

Of course, one of the largest problems which the government will face if the legislation ever becomes officially enforced — and a likely reason why the law has been repeatedly delayed — are virtual private networks such as NordVPN, HideMyAss! and Cyberghost, which allow users to browse the internet anonymously, and even appear to be doing so from a country completely different to their actual location.

With the UK being the only democratic country to so far attempt to block pornography, the “Great Firewall” is likely to be one with many holes in it.

This article was updated on 2 May 2019 to clarify language around age verification systems.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1556793072006-c7e3356d-4e49-5″ taxonomies=”4883″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

23 Sep 2015 | Magazine

In conjunction with the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015, we will be publishing a series of articles that complement many of the upcoming debates and discussions. We are offering these articles from Index on Censorship magazine for free (normally they are held within our paid-for archive) as part of our partnership with the festival. Below is an article by author Erica Jong, on pornographic material in art and literature, taken from our summer 1995 issue. It’s a great starting point for those who plan to attend The body politic: censorship and the female body session at the festival this year.

Index on Censorship is a global quarterly magazine with reporters and contributing editors around the world. Founded in 1972, it promotes and defends the right to freedom of expression.

Pornographic material has been present in the art and literature of every society in every historical period. What has changed from epoch to epoch – or even from one decade to another – is the ability of such material to flourish publicly and to be distributed legally.

After nearly 100 years of agitating for freedom to publish, we find that the enemies of freedom have multiplied, rather than diminished. They are Christians, Muslims, oppressive totalitarian regimes, even well- meaning social libertarians who happen to be feminists, teachers, school boards, librarians. This should not surprise us since, as Margaret Mead pointed out 40 years ago, the demand for state censorship is usually ‘a response to the presence within the society of heterogeneous groups of people with differing standards and aspirations.’ As our culture becomes more diverse, we can expect more calls for censorship rather than fewer.

Mark Twain’s notorious 1601 ... Conversation As It Was By The Social Fireside, In The Time of The Tudors fascinates me because it demonstrates Mark Twain’s passion for linguistic experiment and how allied it is with his compulsion toward ‘deliberate lewdness’.

The phrase ‘deliberate lewdness’ is Vladimir Nabokov’s. In a witty afterword to his ground-breaking 1955 novel Lolita, he links the urge to create pornography with ‘the verve of a fine poet in a wanton mood’ and regrets that ‘in modern times the term “pornography” connotes mediocrity, commercialism and certain strict rules of narration.’ In contemporary porn, Nabokov says, ‘action has to be limited to the copulation of cliches.’ Poetry is always out of the question . ‘Style, structure, imagery should never distract the reader from his tepid lust.’

In choosing to write from the point of view of ‘the Pepys of that day, the same being cup-bearer to Queen Elizabeth’ in 1601, Mark Twain was transporting himself to a world that existed before the invention of sexual hypocrisy. The Elizabethans were openly bawdy. They found bodily functions funny and sex arousing to the muse. Restoration wits and Augustan satirists had the same openness to bodily functions and the same respect for Eros. Only in the nineteenth century did prudery (and the threat of legal censure) begin to paralyse the author‘s hand. Shakespeare, Rochester and Pope were far more fettered politically than we are, but the fact was that they were not required to put condoms on their pens when the matter of sex arose. They were pleased to remind their readers of the essential messiness of the body. They followed a classical tradition that often expressed moral indignation through scatology, ‘Oh Celia, Celia, Celia shits,’ writes Swift, as if she were the first woman in history to do so. In his so-called ‘unprintable poems’, Swift is debunking the conventions of courtly love – as well as expressing his own deep misogyny – but he is doing so in a spirit that Catullus and juvenal would have recognised. The satirist lashes the world to bring the world to its senses. It does the dance of the satyrs around our follies.

Twain’s scatology serves this purpose as well, but it is also a warm-up for his creative process, a sort of pump-priming. Stuck in the prudish nineteenth century, Mark Twain craved the freedom of the ancients. In championing ‘deliberate lewdness’ in 1601, he bestowed the gift of freedom on himself.

Even more interesting is the fact that Mark Twain was writing 1601 during the very same summer (1876) that he was ‘tearing along on a new book’ – the first 16 chapters of a novel he then referred to as ‘Huck Finn’s autobiograph’. This conjunction is hardly coincidental. 1601 and Huckleberry Finn have a great deal in common besides linguistic experimentation. According to Justin Kaplan, ‘both were implicit rejections of the taboos and codes of polite society and both were experiments in using the vernacular as a literary medium.’

In order to find the true voice of a book, the author must be free to play without fear of reprisals. All writing blocks come from excessive self-judgement, the internalised voice of the critical parent telling the author’s imagination that it is a dirty little boy or girl. ‘Hah!’ says the author, ‘I will flaun t the voice of parental propriety and break free!’ This is why pornographic spirit is always related to unhampered creativity. Artists are fascinated with filth because we know that in it everything human is born. Human beings emerge between piss and shit and so do novels and poems. Only by letting go of the inhibition that makes us bow to social propriety can we delve into the depths of the unconscious. We assert our freedom with pornographic play. If we are lucky, we keep that freedom long enough to create a masterpiece like Huckleberry Finn.

But the two compulsions are more than just related; they are causally intertwined.

When Huckleberry Finn was published in 1885, Louisa May Alcott put her finger on exactly what mattered about the novel even as she condemned it: ‘If Mr Clemens cannot think of something better to tell our pure- minded lads and lasses, he had best stop writing for them.’ What Alcott didn’t know was that ‘our pure-minded lads and lasses’ aren’t. But Mark Twain knew. It is not at all surprising that during that summer of high scatological spirits Twain should also give birth to the irreverent voice of Huck. If Little Women fails to go as deep as Twain’s masterpiece, it is precisely because of Alcott’s concern with pure mindedness. Niceness is ever the enemy of art. If you worry about what the neighbours, critics, parents and supposedly pure-minded censors think, you will never create a work that defies the restrictions of the conscious mind and delves into the world o f dreams.

The artist needs pornography as a way into the unconscious and history proves that if this licence is not granted, it will be stolen. Mark Twain had 1601 privately printed. Picasso kept pornographic notebooks that were only exhibited after his death.

1601 is deliberately lewd. It delights in stinking up the air of propriety. It delights in describing great thundergusts of farts which make great stenches and pricks which are stiff until cunts ‘take ye stiffness out of them’. In the midst of all this ribaldry, the assembled company speaks of many things – poetry, theatre, art, politics. Twain knew that the muse flies on the wings of flatus, and he was having such a good time writing this Elizabethan pastiche that the humour shines through a hundred years and twenty later. I dare you to read 1601 without giggling and guffawing.

Erica Jong became internationally famous in 1973-4 with the publication of her novel Fear of Flying, which sold over 10 million copies worldwide. She has also written several collections of poetry and six further novels, most recently Any Woman’s Blues

Excerpted from a paper delivered at a conference on Expression, Offence and Censorship, organised by the Institute for Public Policy Research in June 1995. A full report of the conference, including contributions from Bernard Williams, Michael Grade, Clare Short MP and Chris Smith MP will be published shortly. Details from IPPR, 30-32 Southampton Street, London WC2E 7RA, UK

© Erica Jong and Index on Censorship

Join us on 25 October at the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015 for Question Everything an unconventional, unwieldy and disruptive day of talks, art and ideas featuring a broad range of speakers drawn from popular culture, the arts and academia. Moderated by Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg.

This article is part of the summer 1995 issue of the global quarterly Index on Censorship magazine. Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

29 Apr 2014 | Digital Freedom, News, United Kingdom, Young Writers / Artists Programme

17 Apr 2014 | Digital Freedom, News, United Kingdom

(Shutterstock)

James Brokenshire was giving an interview to the Financial Times last month about his role in the government’s online counter-extremism programme. Ministers are trying to figure out how to block content that’s illegal in the UK but hosted overseas. For a while the interview stayed on course. There was “more work to do” negotiating with internet service providers (ISPs), he said. And then, quite suddenly, he let the cat out the bag. The internet firms would have to deal with “material that may not be illegal but certainly is unsavoury”, he said.

And there it was. The sneaking suspicion of free thinkers was confirmed. The government was no longer restricting itself to censoring web content which was illegal. It was going to start censoring content which it simply didn’t like.

If you call the Home Office they will not tell you what Brokenshire meant. Does it mean “unsavoury” material will be forced onto ISP’s filtering software? They won’t say. Very probably they do not know.

There is a lack of understanding at the Home Office of what they are trying to achieve, of how one might do so, and, more fundamentally, of whether one should be trying at all.

This confusion – more of a catastrophe of muddled thinking than a conspiracy – is concealed behind a double-locked system preventing any information getting out about the censorship programme.

It is a mixture of intellectual inadequacy, populist hysteria, technological ignorance and plain old state secrets. And it could become a significant threat to free speech online.

The Home Office’s current over-excitement stems from its victory over the ISPs last year.

Ministers, from New Labour onward, have always tried to bully ISPs with legislation if they refuse to sign up to ‘voluntary agreements’. It rarely worked.

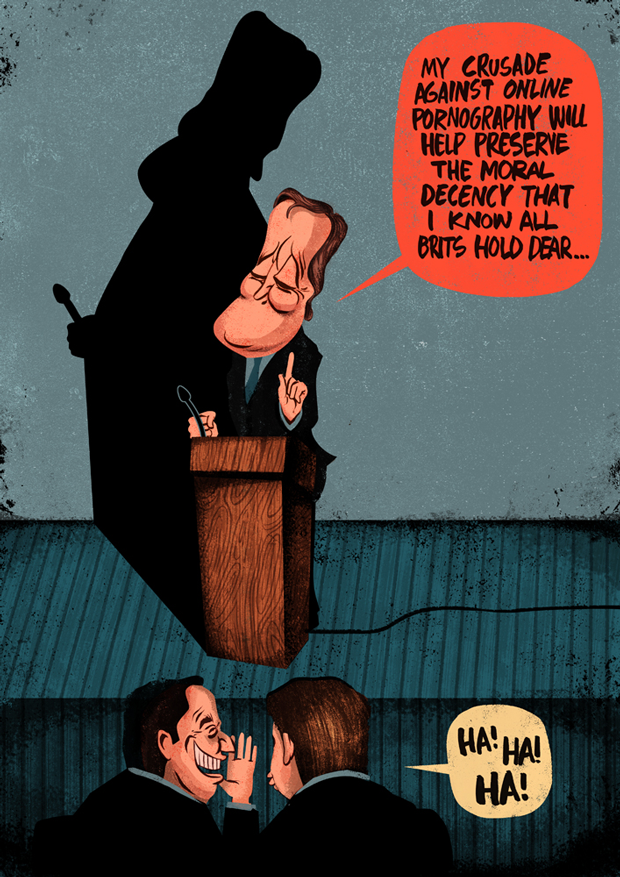

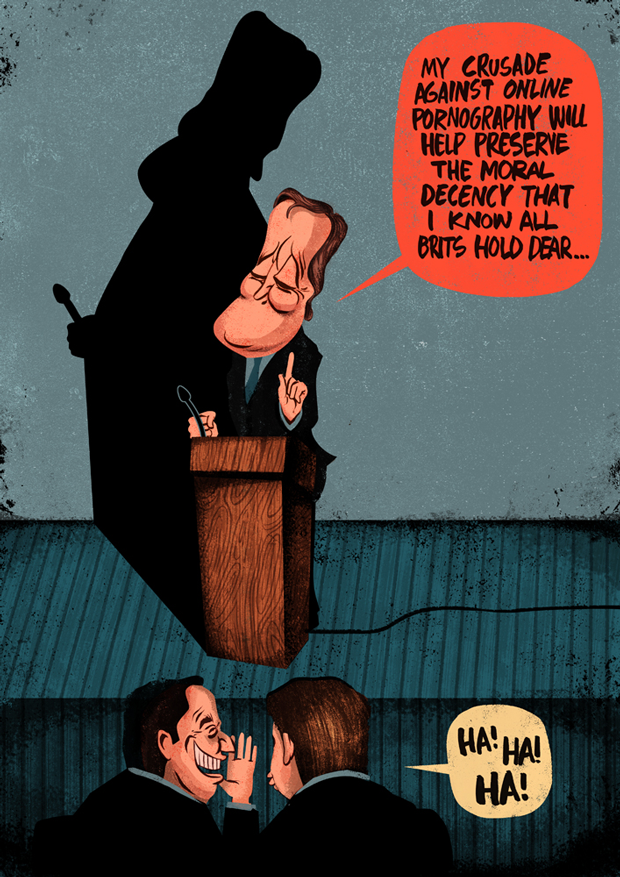

But David Cameron positioned himself differently, by starting up an anti-porn crusade. It was an extremely effective manouvre. ISPs now suddenly faced the prospect of being made to look like apologists for the sexualisation of childhood.

Or at least, that’s how it was sold. By the time Cameron had done a couple of breakfast shows, the precise subject of discussion was becoming difficult to establish. Was this about child abuse content? Or rape porn? Or ‘normal’ porn? It was increasingly hard to tell.

His technological understanding was little better. Experts warned that the filtering software was simply not at the level needed for it fulfill politicians’ requirements.

It’s an old problem, which goes back to the early days of computing: how do you get a machine to think like a person? A human can tell the difference between images of child abuse and the website of child support group Childline. But it has proved impossible, thus far, to teach a machine about context. To filters, they are identical.

MPs like filtering software because it seems like a simple solution to a complex problem. It is simple. So simple it does not exist. Once the filters went live at the start of the year, an entirely predictable series of disasters took place.

The filters went well beyond what Cameron had been talking about. Suddenly, sexual health sites had been blocked, as had domestic violence support sites, gay and lesbian sites, eating disorder sites, alcohol and smoking sites, ‘web forums’ and, most baffling of all, ‘esoteric material’. Childline, Refuge, Stonewall and the Samaritans were blocked, as was the site of Claire Perry, the Tory MP who led the call for the opt-in filtering. The software was unable to distinguish between her description of what children should be protected from and the things themselves.

At the same time, the filtering software was failing to get at the sites it was supposed to be targeting. Under-blocking was at somewhere between 5% and 35%.

Children who were supposed to be protected from pornography were now being denied advice about sexual health. People trying to escape abuse were prevented from accessing websites which could offer support.

And something else curious was happening too: A reactionary view of human sexuality was taking over. Websites which dealt with breast feeding or fine art were being blocked. The male eye was winning: impressing the sense that the only function for the naked female body was sexual.

It was a staggering failure. But Downing Street was pleased with itself, it had won. The ISPs had surrendered. The Washington Post described it as “some of the strictest curbs on pornography in the Western world” – music to Cameron’s ears. Suddenly the terms of the debate started shifting. Dido Harding, the chief executive of TalkTalk, was saying the internet needed a “social and moral framework”.

So instead of proving the death knell for government-mandated internet censorship, the opt-in system became a precursor for a more extensive ambition: banning extremism.

If targeting porn without also blocking sexual health websites was hard, countering terrorism was even more difficult. After all, the line between legitimate political debate and inciting terrorism is blurred and subjective. And that’s not even to address other pieces of problematic legislation, such as the Racial and Religious Hatred Act 2006, which bans incitement to hatred against religions.

Even trying to block what everyone agrees is extremist content is highly controversial. Anti-extremism group Quilliam and security experts at the Royal United Services Institute have warned that closing websites were people are liable to being radicalised actually hinders intelligence services.

A lot of what we know about Brits going off to fight in Syria or elsewhere comes from the fact they write it on message boards. Blocking them just reduces your ‘intelligence take’. Groups like Quilliam also use those sites to go in and engage with people, offering them a ‘counter-narrative’. Blocking the sites prevents them doing their work.

The Home Office mulled whether to add extremism – and Brokenshire’s “unsavoury content” – to something called the Internet Watch Foundation (IWF) list.

The list was supposed to be a collection of child abuse sites, which were automatically blocked via a system called Cleanfeed. But soon, criminally obscene material was added to it – a famously difficult benchmark to demonstrate in law. Then, in 2011, the Motion Picture Association started court proceedings to add a site indexing downloads of copyrighted material.

There are no safeguards to stop the list being extended to include other types of sites.

This is not an ideal system. For a start, it involves blocking material which has not been found illegal in a court of law. The Crown Prosecution Service is tasked with saying whether a site reaches the criminal threshold. This is like coming to a ruling before the start of a trial. The CPS is not an arbiter of whether something is illegal. It is an arbiter, and not always a very good one, of whether there is a realistic chance of conviction.

As the IWF admits on its website, it is looking for potentially criminal activity – content can only be confirmed to be criminal by a court of law. This is the hinterland of legality, the grey area where momentum and secrecy count for more than a judge’s ruling.

There may have been court supervision in putting in place the blocking process itself but it is not present for individual cases. Record companies are requesting sites be taken down and it is happening. The sites are only being notified afterwards, are only able to make representations afterwards. The tradional course of justice has been turned on its head.

The possibilities for mission creep are extensive. In 2008, the IWF’s director of communications claimed the organisation is opposed to censorship of legal content, but just days earlier it had blacklisting a Wikipedia article covering the Scorpions’ 1976 album Virgin Killer and an image of its original LP cover art.

Sources close to the ISPs say they were asked to take the IWF list wholesale – including pages banned due to extremism – and block them for all their customers, whether they had signed into the filtering option or not.

They’ve proved commendably reluctant, although their reticence is as much about legal challenges as a principled stance on free speech. Regardless, they seem to be insisting that universal blocking can only be carried out with a court order. Brokenshire is then left trying to get them to include it in their optional, opt-in filter.

We don’t know if he’s succeeded in that. The Home Office are resistant to giving out any information. They direct inquiries to the Department of Culture, Media and Sport or ISPs themselves, who really have no idea what’s going on. They refuse to answer any questions on Cleanfeed, saying it is a privately owned service – a fact which is technically true and entirely misleading.

It is not conspiracy. It is plain old cock up, combined with an inadequate understanding of the proper limit of their powers.

The left hand does not know what the right hand is doing. Even inside departments of the Home Office they do not know what they are trying to achieve.

The policy formation is weak and closed. The industry is not in the loop. Media inquiries are being dismissed. The technological understanding is startlingly naive.

The prospect of a clamp down on dissent is real. It would come slowly, incrementally – a cack-handed government response to technological change it does not understand.

We must be grateful for James Brokenshire. His slip ups are the best source of information we have.

This article was originally posted on 17 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org