22 Jul 2019 | Campaigns -- Featured, Media Freedom, media freedom featured, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”108086″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen

European Commission

Rue de la Loi 200

1049 Brussels

Belgium

19 July 2019

Dear President von der Leyen,

We are writing as members of the press freedom community to congratulate you on your appointment as President of the European Commission, and to urge you to ensure that media freedom, the protection of journalists, and EU citizens’ access to information are top political priorities over the coming term of your Commission.

The last Commission took important steps to address media freedom. But given the rapidly changing media environment, increasingly severe threats and restrictions to press freedom, and the recent murders of journalists, more must be done. We, the undersigned organizations, strongly urge you to appoint a Vice-President of the new Commission with a clear and robust mandate to use all available EU mechanisms, including policy, legislation, and budget, to defend press freedom and the safety of journalists. In particular, we urge you to explicitly list this mandate in your mission letter to one of the Vice-Presidents establishing it as a political priority over the next five-year term.

We ask that the Vice-President have a sufficiently robust and far-ranging mandate to address the following areas of reform:

- Creating an enabling legal and regulatory environment for free, independent, pluralistic, and diverse media and the safety of journalists, whether staff, freelancers, or bloggers. Journalists need to be protected from judicial harassment, arbitrary surveillance, defamation, overly broad national security and anti-terrorist legislation, as well as SLAPP and tax laws.

- Protecting journalists, freelancers, and bloggers from physical, legal, psychological, and digital threats, and ensuring access to effective protection and prevention measures and mechanisms, with specific attention to the risks facing female journalists.

- Combating impunity for all attacks against journalists, freelancers, and bloggers, including support and capacity-building for law enforcement, prosecutors, and the judiciary and the development of specialized protocols for investigations.

- Continuing to combat disinformation through robust public defense of independent journalism and its critical importance in democracy. This should accompany efforts to increase public understanding of media freedoms, supporting social media self-regulation, and building media literacy.

- Supporting sustainable models for independent journalism in promoting media independence, pluralism, and diversity, as well as allowing for effective self-regulation, capacity building, and training.

Media freedom and pluralism are pillars of modern democracy. For the next Commission to guarantee European citizens their right to access to information, it must use the coming term to address the numerous threats to journalism. We hope you will take steps to ensure it does.

We would welcome the opportunity to meet with you and thank you in advance for taking our concerns into consideration. We look forward to receiving your response.

Sincerely,

Alliance Internationale de Journalistes

Article 19

Association of European Journalists

Committee to Protect Journalists

English PEN

European Federation of Journalists

European Journalism Centre

European Media Initiative

European Centre for Press and Media Freedom

Free Press Unlimited

Global Forum for Media Development

IFEX

Index on Censorship

International Press Institute

Media Diversity Institute

PEN International

Reporters Without Borders

Rory Peck Trust

South East Europe Media Organisation (SEEMO)

World Association of News Publishers (WAN-IFRA)[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

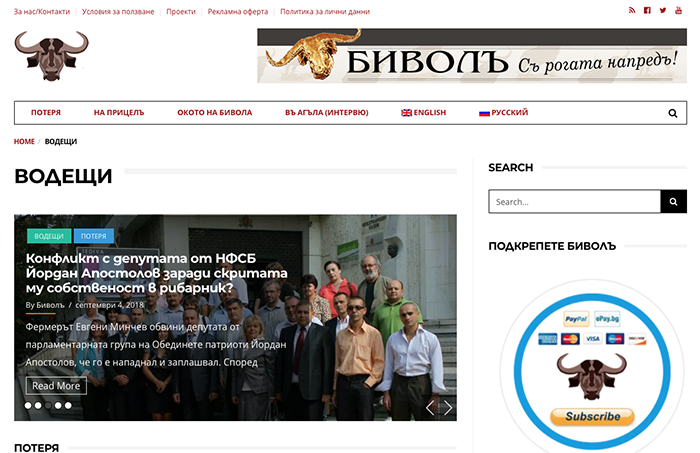

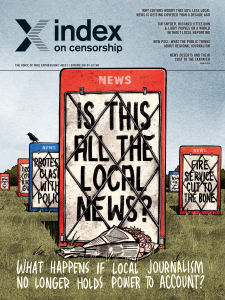

26 Mar 2019 | Magazine, Magazine Editions, Volume 48.01 Spring 2019

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”With contributions from Richard Littlejohn, Libby Purves, Michal Hvorecký, Karoline Kan, Andrew Morton, Jeffrey Wasserstrom, Rituparna Chatterjee and Julie Posetti”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Is this all the local news? The spring 2019 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

The spring 2019 edition of Index on Censorship looks at local news in the UK and around the world and what happens when local journalism no longer holds power to account.

Our exclusive survey of editors and journalists in the UK shows that 97% are worried that local newspapers don’t have the resources any more to hold power to account. Meanwhile the older population tell us they are worried that the public is less well informed than it used to be. Local news reporting is in trouble all over the world. In the USA Jan Fox looks at the news deserts phenomenon and what it means for a local area to lose its newspaper. Karoline Kan writes from China about how local newspapers, which used to have the freedom to cover crises and hold the government to account, are closing as they come increasingly under Communist Party scrutiny. Veteran English radio journalist Libby Purves tells editor Rachael Jolley that local newspapers in the UK used to give a voice to working-class people and that their demise may have contributed to Brexit. In India Rituparna Chatterjee finds a huge appetite for local news, but discovers, with some notable exceptions, that there is not enough investment to satisfy demand. “Fake news” is on the rise, and journalists are vulnerable to bribery. Meanwhile Mark Frary examines how artificial intelligence is being used to write news stories and asks whether this is helping or hindering journalism. Finally an extract from the dystopian Slovak novel Troll, Michal Hvorecký published in English for the first time imagines an outpouring of state-sponsored hate

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Special Report: Is this all the local news?”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The future is robotic by Mark Frary Would journalists have more time to investigate news stories if robots did the easy bits?

Terrorising the truth by Stephen Woodman Journalists on the US border are too intimidated by drug cartels to report what is happening

Switched off by Irene Caselli After years as a political football, Argentinian papers are closing as people turn to the internet for news

News loses by Jan Fox Thousands of US communities have lost their daily papers. What is the cost to their area?

Stripsearch by Martin Rowson On the death of local news

What happens when our local news disappears by Tracey Bagshaw How UK local newspapers are closing and coverage of court proceedings is not happening

Who will do the difficult stories now? by Rachael Jolley British local newspaper editors fear a future where powerful figures are not held to account, plus a poll of public opinion on journalism

“People feel too small to be heard” by Rachael Jolley Columnist Libby Purves tells Index fewer working-class voices are being heard and wonders whether this contributed to Brexit

Fighting for funding by Peter Sands UK newspaper editors talk about the pressures on local newspapers in Britain today

Staying alive by Laura Silvia Battaglia Reporter Sandro Ruotolo reveals how local news reporters in southern Italy are threatened by the Mafia

Dearth of news by Karoline Kan Some local newspapers in China no longer dig into corruption or give a voice to local people as Communist Party scrutiny increases

Remote controller by Dan Nolan What happens when all major media, state and private, is controlled by Hungary’s government and all the front pages start looking the same

Rocky times by Monica O’Shea Local Australian newspapers are merging, closing and losing circulation which leaves scandals unreported

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Global View”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”In Focus”][vc_column_text]

Turning off the searchlights by Alessio Perrone The Italian government attempts to restrict coverage of the plight of refugees crossing the Mediterranean

Standing up for freedom Adam Reichardt A look at Gdańsk’s history of protest and liberalism, as the city fights back after the murder of mayor Paweł Adamowicz

After the purge by Samuel Abrahám and Miriam Sherwood This feature asks two writers about lessons for today from their Slovak families’ experiences 50 years ago

Fakebusters strike back by Raymond Joseph How to spot deep fakes, the manipulated videos that are the newest form of “fake news” to hit the internet

Cover up by Charlotte Bailey Kuwaiti writer Layla AlAmmar discusses why 4,000 books were banned in her home country and the possible fate of her first #MeToo novel

Silence speaks volumes by Neema Komba Tanzanian artists and musicians are facing government censorship in a country where 64 new restrictions have just been introduced

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Culture”][vc_column_text]

The year of the troll by Michal Hvorecký This extract from the novel Troll describes a world where the government controls the people by spewing out hate 24 hours a day

Ghost writers by Jeffrey Wasserstrom The author and China expert imagines a fictional futuristic lecture he’s going to give in 2049, the centenary of Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four

Protesting through poetry by Radu Vancu Verses by one of Romania’s most renowned poets draw on his experience of anti-corruption protests in Sibiu

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Column”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Endnote”][vc_column_text]

Press freedom: EU blind spot? By Sally Gimson Many European countries are violating freedom of the press; why is the EU not taking it more seriously?

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online, in your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”105481″ img_size=”medium”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]The spring 2019 magazine podcast, featuring interviews with editor of chinadialogue, Karoline Kan; director of the Society of Editors in the UK Ian Murray and co-founder of the Bishop’s Stortford Independent, Sinead Corr. Index youth board members Arpitha Desai and Melissa Zisingwe also talk about local journalism in India and Zimbabwe

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”105481″ img_size=”medium”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]The spring 2019 magazine podcast, featuring interviews with editor of chinadialogue, Karoline Kan; director of the Society of Editors in the UK Ian Murray and co-founder of the Bishop’s Stortford Independent, Sinead Corr. Index youth board members Arpitha Desai and Melissa Zisingwe also talk about local journalism in India and Zimbabwe

LISTEN HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

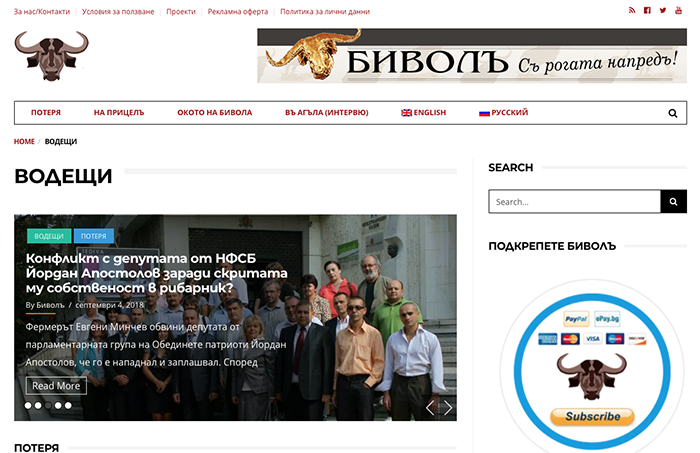

7 Sep 2018 | Bulgaria, Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

After Bulgarian news reporter Maria Dimitrova helped expose an organised crime group from Vratsa’s involvement in fraud and drug trafficking, she received threatening text and Facebook messages. One of the gang’s victims, who spoke to Dimitrova for her report, was later attacked by three unidentified men. According to investigative journalism outlet Bivol, investigators from the Vratsa police precinct, where Dimitrova was questioned, “acted cynically and with disparagement”.

In November 2017, Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom platform, which monitors press freedom violations in 43 countries, revealed that members of the gang had planned to murder Georgi Ezekiev, the publisher of the Zov News, where Dimitrova works/had worked.

Zoltan Sipos, MMF’s Bulgaria correspondent, says such violations have had a marked impact on the country’s media, adding that “sophisticated” soft censorship is a “big problem”.

“Self-censorship is also an issue in Bulgaria, though the nature of this form of censorship is that its existence is difficult to prove unless journalists come forward with their experiences,” he says.

Under increasing pressure from the government and a media environment becoming more and more censored, journalists within Bulgaria are finding themselves in danger. With an inadequate legal framework, pressure from editors and other limitations, journalists regularly self-censor or suffer the consequences.

Sipos has made 40 reports of media freedom violations in Bulgaria since the project’s launch in 2014.

In May 2018, a report was filed of an investigative journalist was assaulted outside his home in Cherven Bryag, a town in northwestern Bulgaria.

Hristo Geshov writes for the regional investigative reporting website Za Istinata, works with journalistic online platform About the Truth and hosts a programme called On Target on YouTube. In a Facebook post, he said the attack was a response to his investigative reporting and “to the warnings [he] sent to the authorities about the management of finances by the Cherven Bryag municipal government”.

Geshov faced harassment after publishing a series of articles about government irregularities, in which he claimed that three municipal councillors were using EU funds to renovate their homes.

“It is unacceptable that Bulgarian journalists should be the target of physical attacks and that there should even be plots to kill them, simply because they are engaged in investigating official corruption,” Paula Kennedy, the assistant editor for Mapping Media Freedom, said.

“The authorities need to take such attacks seriously and do more to ensure adequate protection for those targeted.”

Bulgarian journalists are also being limited by legislation designed by politicians as a means of censorship. Backed by Bulgarian MPs, amendments to the Law for the Compulsory Depositing of Print Media would force media outlets in the country to declare any funding, such as grants, donations and other sources of income that they receive from foreign funders. Ninety-two members of parliament voted for the amendments on the first reading on 4 July, with 12 against and 28 abstentions. Unlike most legislation, there was no parliamentary debate beforehand.

With the second reading due in September, when it will have to be once again approved by parliament, and the president still has the right to veto it, amendments would force outlets to clearly state the current owner on their website, how much funding they received, who it was from and what it is for.

MPs claim the aim is to make the funding of media organisations more transparent.

Referred to as “Delyan Peevski’s media law”, the amendments were first proposed in February 2018 by MP Deylan Peevski, a politician and media owner. Almost 80% of Bulgarian print media and its distribution is controlled by Peevski, former head of Bulgaria’s main intelligence agency and owner of the New Bulgarian Media Group.

The amendments will create two categories of media, separating those funded by grants and those who receive funding from “normal” practices such as bank loans, which they are not obliged to declare. Peevski-owned media is funded predominantly through bank loans, with his family receiving loans from now-bankrupt Corporate Commercial Bank.

There are few independent media outlets remaining in Bulgaria, with fears the new law will only increase the level of self-censorship within the country. Amendments will put additional pressure on media outlets that rely on foreign grants and donations to maintain their editorial independence.

Atanas Tchobanov, co-founder of Bivol, told MMF the amendments are a way to “whiten [Peevski’s] image”, adding: “The bill is exposing mainly the small media outlets, living on grants and donations. If a businessman gives [Bivol] €240 per year with a €20 month recurrent donation and we disclose his name, his business might be attacked by the Peevski’s controlled tax office and prosecution.

“Delyan Peevski has blatantly lied about his media ownership in the past. Then, miraculously, he started declaring millions in income, but this was never found strange by any anti-corruption institution.”

The level of transparency required of independent media owners has become a major issue within the country, threatening independent journalism and editorial independence.

Speaking at the biannual Time to Talk debate meeting in Amsterdam, Irina Nedeva from The Red House, the centre for culture and debate in the Bulgarian capital Sofia, Bulgaria, tells Index: “We live in very strange media circumstances. On the surface, it might look like Bulgaria has many different private media print outlets, radio stations, many different private tv channels, but in fact what we see is that especially in the print press, more of the serious newspapers cease to exist.”

“They don’t exist anymore, they can’t afford to exist because the business model has changed and what we see is that we have many tabloids,” she adds. “These tabloids are one and the same just with reshaped sentences.”

Nedeva is concerned that such publications don’t adequately criticise the government or businesses. “They criticise only the civil society organisations that dare to show the wrongdoings of the government for example.”

In an effort to examine media ownership within Bulgaria, the European Centre for Press and Media Freedom undertook a press freedom mission in June 2018. The mission found money from government and advertising is distributed to media considered to be compliant. EU funding is controlled by the government, giving those in charge the power to decide which publications receive what. This has created an atmosphere of self-censorship, dubbed “highly corrupting” by an ECPMF into press freedom in Bulgaria.

“There seems to be no enabling environment, politically or economically for independent journalism and media pluralism”, describing the media situation as a “systemic symptom of a captured state,” Nora Wehofsits, advocacy officer for ECPMF tells Index. “If the new media law is accepted, it could have a chilling effect on media and journalists working for “the wrong side”, as the media law could be used arbitrarily in order to accuse and silence them.”

Lada Price, a journalism lecturer at Sheffield Hallam University and Director of Education at the Centre for Freedom of the Media describes for Index the role the media owners play: “There’s lots of abuse of power for personal gain and I think, therein lies the biggest issue for free speech in Bulgaria. Media outlets are not being bought for commercial purposes, but for political purposes. They like to follow their own political and business agendas, and they’re not afraid to use that power to censor criticisms of government or any corporate partners.”

Price says that while the constitution guarantees the right to receive and disseminate information, the media landscape in Bulgaria is very hostile for journalism “because of the informal system of networks, which is dominated by mutual, beneficial relationships”.

“There is a very close-knit political, corporate and media elite and that imposes really serious limits on what journalists can and can not report,” she says. “If you speak to journalists, they might say whoever pays the bill has a say on what gets published and that puts limits on independence. There is no direct censorship, but lots of different ways to make journalists self-censor.”

ECPMF also said in its report into press freedom in Bulgaria that the difficulties media workers face are due to the current censorship climate, adding: “It is difficult to produce quality journalism due to widespread self-censorship and the struggle to stay independent in a highly dependent market.”

Funding from the EU and its allocation has become a controversial issue for media outlets in the country. In January 2018 ECPMF called for fair distribution of EU funds to media in Bulgaria, saying “the Bulgarian government should disseminate funds on an equal basis to all of the media, also to the ones who are critical of the government”. It also requested that the EU actively monitor how EU taxpayers’ money is spent in Bulgaria.

Bulgarian journalism is heavily reliant on EU funding and during the economic crisis of 2008/2009, advertisement revenues fell, making both print media and broadcasters much more dependent on state subsidies.

“When it comes to public broadcasters, they are basically fully dependent on the state budget,” says Price. “That means funding comes from whoever is in power, so they are very careful of what kind of criticisms [they publish], who they criticise. Their directors also get appointed by the majority in parliament.”

“The funding schemes that put restrictions on journalism is by EU funding, which shouldn’t really happen,” she adds. “But if you have your funding which is aimed at information campaigns then that is sometimes channelled by government agencies, but only towards selected media, which we see in the form of state advertising, in exchange for providing pro-government politic coverage.”

According to the US State Department’s annual report on human rights practices, released in April 2018, media law in Bulgaria is being used to silence and put pressure on journalists. ECPMF, in a report released in May 2018, described the current legislation as not adequately safeguarding independent editorial policies or prevent politicians from owning media outlets or direct/indirect monitoring mechanisms.

This was also reiterated by the US State Department’s report, which highlighted concerns that journalists who reported on corruption face defamation suits “by politicians, government officials, and other persons in public positions”.

“According to the Association of European Journalists, journalists generally lost such cases because they could rarely produce hard evidence in court,” the US State Department said.

The report also showed journalists in the country continue to “report self-censorship, [and] editorial prohibitions on covering specific persons and topics, and the imposition of political points of view by corporate leaders,” while highlighting persistent concerns about damage to media pluralism due to factors such as political pressure and a lack of transparency in media ownership.

Nelly Ognyanova, a prominent Bulgarian media law expert, tells Index that the biggest problem Bulgaria faces is “the lack of rule of law”.

“In the years since democratic transition, there is freedom of expression in Bulgaria; people freely criticise and express their opinions,” she says. “At the same time, the freedom of the media depends not only on the legal framework.”

In her view, the media lacks freedom because “their funding is often in dependence on power and businesses”, and “the state continues to play a key role in providing a public resource to the media”.

“The law envisages the independence of the media regulator, the independence of the public media, media pluralism. This is not happening in practice. There can be no free media, neither democratic media legislation, in a captured state.”[/vc_column_text][vc_raw_html]JTNDaWZyYW1lJTIwd2lkdGglM0QlMjI3MDAlMjIlMjBoZWlnaHQlM0QlMjIzMTUlMjIlMjBzcmMlM0QlMjJodHRwcyUzQSUyRiUyRm1hcHBpbmdtZWRpYWZyZWVkb20udXNoYWhpZGkuaW8lMkZzYXZlZHNlYXJjaGVzJTJGNzUlMkZtYXAlMjIlMjBmcmFtZWJvcmRlciUzRCUyMjAlMjIlMjBhbGxvd2Z1bGxzY3JlZW4lM0UlM0MlMkZpZnJhbWUlM0U=[/vc_raw_html][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1536667459548-83ac2a47-7e8a-7″ taxonomies=”8996″][/vc_column][/vc_row]