9 Nov 2015 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan News, Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News

November is a month of historical anniversaries. Last Thursday was the annual commemoration of the foiling of the Gunpowder Plot and yesterday the UK fell silent to pay tribute to its war dead on Remembrance Sunday.

A much lesser-known date — at least to anyone outside Azerbaijan — is the country’s Flag Day, the celebration of the tricolour which was first adopted as the national flag on 9 November 1918.

The flag hoisted in the capital city of Baku was once confirmed by the Guinness Book of Records as being the tallest in the world. It flies on a pole 162 meters high and measures 70 by 35 meters. While the flag underwent a hiatus while Azerbaijan was part of the Soviet Union between 1920 and 1991, it is now a proud symbol of the country’s independence.

The tricolour consists of three horizontal stripes, each being deeply symbolic. The blue stripe stands for the Turkish origin of Azerbaijani people and the green stripe at the bottom expresses affiliation to Islam. Neither can be disputed. The red stripe in the middle, however, is problematic. It stands for progress, modernisation and democracy.

But Azerbaijan’s status as a modern democracy is less than convincing. Sure, the country has made some significant strides since the collapse of communism. It boasts a 98.8% literacy rate, and since the early 2000s spending on education has increased five-fold, for example.

However, there is an illusion of material progress in Azerbaijan. As Index on Censorship has been reporting, the country has experienced an unprecedented crackdown on human rights and freedoms.

Little over a week ago, Azerbaijan held a parliamentary election while an estimated 20 prisoners of conscience sat in prison. Azerbaijani journalist Khadija Ismayilova, who was sentenced to seven years and six months in jail in September for exposing state corruption, is one of them. The award-winning journalist was detained on 5 December 2014 and eventually convicted of libel, tax evasion and illegal business activity.

President Ilham Aliyev’s government has long claimed that “all freedoms are guaranteed in Azerbaijan“. Given his government’s lack tolerance for dissent, this clearly isn’t the case. Leyla Yunus, founder and director of the Institute for Peace and Democracy, and her husband, historian Arif Yunus — both outspoken critics of the government — have been detained since summer 2014 when they were arrested on charges of treason and fraud. On 13 August, the Baku Court on Grave Crimes sentenced Leyla to eight years and six months in prison and Arif to seven years in prison.

Democracy activist Rasul Jafarov, human rights lawyer Intigam Aliyev and journalist Seymur Hezi are also serving prison sentences on charges that were widely condemned for being politically motivated to silence outspoken critics of the government of President Aliyev.

The list of journalists and activists who have been arrested, abused, beaten and even killed goes on. In June 2015, on the eve of the inaugural European Games in Baku, activists from Amnesty International and Platform were banned from entering the country. Both organisations have been highly critical of Aliyev’s government, and its continuing targeting, jailing and prosecution dissenters. Even The Guardian was blocked from reporting on the games when its reporter was barred.

The ruling party in Azerbaijan may have won an outright majority in this month’s elections, cementing Aliyev’s hold on power. However, opposition parties boycotted the vote over concerns it was neither free nor fair. Even the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) refused to monitor the election after authorities severely limited its ability to observe the vote effectively. It marks the first time since 1991 that the OSCE has not monitored an Azerbaijani election and highlights that the situation in the country is far from progressive.

Flag Day is set against a backdrop of arrests and human rights abuses. If Azerbaijan is to earn its stripes, the authorities must uphold their human rights obligations, release all prisoners of conscience and allow for elections that meet basic democratic standards.

This article was posted on 9 November 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

1 Sep 2015 | About Index, Campaigns, Press Releases, Turkey, United Kingdom

Wednesday 2 September:

The Foreign and Commonwealth Office issued the following statement:

“We are concerned at the arrest of two British journalists in Diyarbakir on 31 August, who have been charged with assisting a terrorist organisation. The journalists have been given access to a lawyer and were in direct contact with consular officials within 24 hours of their detention.

“Respect for freedom of expression and the right of media to operate without restriction are fundamental in any democratic society. Turkey is a state party to the European Convention on Human Rights and International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. We would expect the Turkish authorities to uphold the obligations enshrined in those agreements.”

Tuesday 1 September:

Freedom of expression charities have written to UK Foreign Secretary Philip Hammond urging the UK to speak out publicly in defence of freedom of expression following the arrest of two British journalists and an Iraqi translator in Turkey under terror legislation.

The journalists and their fixer were were formally charged by a Turkish court on Monday with ‘aiding a terrorist organisation’. Vice News has described the charges as completely baseless.

The letter from PEN International, English PEN and Index on Censorship highlights the deteriorating situation for media in Turkey and urges Foreign Secretary Philip Hammond to speak out publicly against the arrests.

“Coming shortly after the equally unjust sentencing of Al Jazeera journalists in Egypt, we would note also the worrying increase in the use of terror laws to stifle a free and independent media globally and hope the UK will use its international position to help reverse this disturbing trend,” the groups say in the letter.

The groups have also written to the Council of Europe, of which Turkey and the UK are members, to express their concerns.

A copy of the letter can be found below.

Dear Mr Hammond,

We are writing to you on behalf of Index on Censorship, English PEN and PEN International, charities that campaign for freedom of expression in the UK and globally, to urge the immediate intervention of the British government in the case of three VICE News journalists, including two Britons, who have been charged with terror offences by the Turkish government.

The two British reporters, VICE News journalists Jake Hanrahan and Philip Pendlebury, along with their fixer, Iraqi translator and journalist Mohammed Ismael Rasool, were formally charged by a Turkish court on Monday with ‘aiding a terrorist organisation’. We believe these charges to be baseless.

The three were detained by police with a fourth member of their team as they filmed in the south-east region of Diyarbakir on Thursday. Police interrogated them about alleged links to Islamic State and Kurdish militants.

You will be aware that the Turkish government’s routine use of counter-terrorism charges against journalists is a longstanding cause of concern for international human rights organisations and for the media in Turkey. There are rising fears that Turkey is on the brink of a new media crackdown in the run up to the parliamentary elections: Turkish police conducted a raid on the offices of Koza Koza Ipek Media group today, while an Ankara court has ruled in favour of a general search warrant for the Çankaya district of the Turkish capital (where embassies and foreign missions are based) allowing police to make preventative security searches and detentions for 30 days.

We recognise that Turkey is facing a period of heightened tension in the region. However at such a time it is more important than ever that both domestic and international journalists are allowed to do their vital work without intimidation, reporting on matters of global interest and concern.

A member of the Council of Europe, Turkey is a state party to both the European Convention on Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. It is therefore obliged to respect the right to freedom of expression and ensure that journalists are free to gather information without hindrance or threat.

We appreciate the Foreign Office’s consular assistance to the VICE News team and urge you to make a public statement in defence of freedom of expression in Turkey.

Coming shortly after the equally unjust sentencing of Al Jazeera journalists in Egypt, we would note also the worrying increase in the use of terror laws to stifle a free and independent media globally and hope the UK will use its international position to help reverse this disturbing trend.

Yours sincerely,

Jodie Ginsberg

Chief Executive, Index on Censorship

Maureen Freely

President, English PEN

Carles Torner

Executive Director, PEN International

27 Aug 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News

Female journalists and bloggers are increasingly being singled out and fiercely attacked online. (Photo: OSCE)

In a new online column for Index on Censorship, Dunja Mijatović, OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media, discusses relentless attacks on women journalists, and the impact on their lives.

No job comes without sacrifices, but how many downgrading comments, criticism or even threats can one person take before it becomes too much?

Just consider the experiences of a female journalist that I know:

She had her phone number shared on dating websites, her email and other accounts were hacked, she received death threats on Skype, the website publishing her articles was hacked and a sex video was posted with the implication that she had participated in an orgy. Anonymous articles with lies about her and her family were also posted online.

Imagine being forced to shut down your accounts on social media platforms because of such massive attacks with detailed images of rape and other forms of sexual violence.

At one point, you would probably be inclined to ask yourself if it is really worth it. Is this a career I want to continue to pursue?

In the past few years, more and more female journalists and bloggers have been forced to question their profession. Male journalists are also subject to hate speech and online abuse, but research findings suggest that female journalists face a disproportionate amount of gender-based threats and harassment on the internet. They are experiencing what Irina Bokova, director-general of UNESCO, has described as a “double attack”: they are being targeted for being both a journalist and a woman.

How do these attacks affect female journalists’ lives, their work and society in general? Journalists are used to being in the frontline of conflict and they often deal with difficult and even dangerous situations. But what if you cannot shield yourself from these threats? What if the frontline became your own doorstep, your office or your computer screen?

Not only do these kinds of attacks cause severe physiological trauma for journalists and their families, but by constantly being singled out and targeted with abusive comments, many female journalists may re-evaluate the issues they choose to cover. In this way, such attacks pose a clear and present threat to free media and the society as a whole.

Online abuse must be dealt with within the existing human rights framework, with governments committed to protecting journalists’ safety and addressing gender discrimination. Governments must ensure that law enforcement agencies understand the severity of this issue and are equipped with the necessary training and tools to more efficiently investigate and prosecute online threats and abuse.

We have to acknowledge that online threats are as real and unacceptable as threats posed in the offline world. The landmark resolution 20/8 on internet freedom adopted by United Nations Human Rights Council in 2012, affirmed that “the same rights that people have offline must also be protected online, in particular freedom of expression”, and set out a clear path in this respect.

The responsibility to counter online abuse of female journalists does not solely rest with law enforcement agencies, however. The broader media community itself also plays an important role. One of the challenges facing media outlets is how to improve quality of content moderation without invoking censorship.

Sarah Jeong, lawyer, journalist and author of The Internet of Garbage, provides proper context, “moderation paradoxically increases the number of voices heard, because some kinds of speech chills other speech. The need for moderation is sometimes oppositional to free speech, but sometimes moderation aids and delivers more free speech”.

Media outlets need to address the current structures and strategies in place that provide support and relief to journalists who face online abuse. A recent survey of female journalists in the OSCE region carried out by my office suggests that employers’ awareness and active involvement in dealing with these issues is of crucial importance. Unfortunately, the survey also indicated that media outlets are not as involved as they should be.

International organisations should also dedicate resources to tackle this issue, given their widespread reach and vast partnership networks. UNESCO’s work on gender-related aspects of journalists’ safety serves as a good example. In their recent report Building Digital Safety for Journalists, online abuse of female journalists was rightly pointed out as one of the main challenges in building digital safety.

This year I have tried to use my mandate and tools given to me as the OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media to get the OSCE participating states involved. We need to realize that different stakeholders face different challenges, but that each stakeholder’s involvement is a crucial piece of the puzzle in identifying solutions.

To further the discussion on protection of female journalists in the OSCE region, on 17 September my office will host a conference, New Challenges to Freedom of Expression: Countering Online Abuse of Female Journalists, to provide a platform for discussions on best practices and recommendations on combating this dangerous trend. The event will be streamed live on osce.org and will feature presentations by high-level experts from all over the world.

This column was posted on 27 August 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

6 Aug 2015 | mobile, News, South Africa

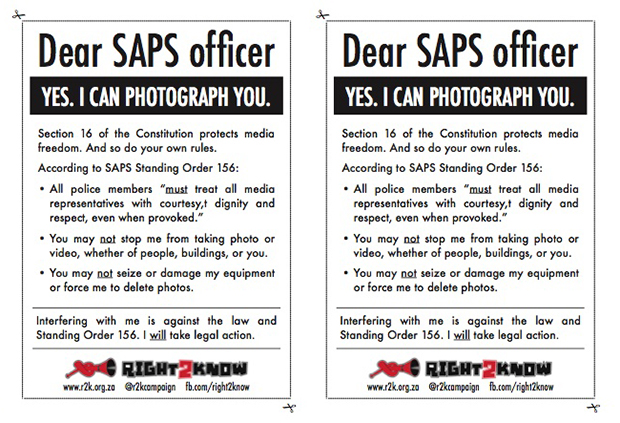

Despite Standing Order 156 incidents of police harassment of journalists continues. (Photo: Jaxons / Shutterstock.com)

Raymond Joseph has joined Index as a columnist

Working as a reporter in the spiraling cauldron of violence in South Africa of 70s and 80s, I learned early on to be wary of the police, who would often harass, bully and even detain journalists for doing their job.

Often it happened when police, armed to the teeth, went into operational mode, firing teargas, baton rounds and even live ammunition to brutally break up protests.

While reporters were also targeted, it was photographers and cameramen who were really in the firing line. Toting cameras, they were easily visible. Their pictures or footage were regularly destroyed by police and their equipment damaged or confiscated.

As a young reporter, I became adept at stashing exposed rolls of film, slipped to me by photographer colleagues, down the front of my trousers to hide them from the police.

Anyone who worked as a journalist in those turbulent times has stories to tell of being pushed around and bullied by the police who saw the media, especially those working for the anti-apartheid era English language Press, as “the enemy”.

Fast forward two decades into post-apartheid South Africa and practically every working journalist also has a story of police harassment to tell, often arising from incidents when they were reporting or filming police officers. Many less serious incidents go unreported, accepted by journalists as part of the job.

This is happening despite the South African Police Service’s own Standing Order 156 that sets out how the police must behave towards the media. The language used is unequivocal and leaves no room for misunderstanding. It makes it clear that police cannot stop journalists from taking photos or filming, including photographing police officers. It also states that “under no circumstances” may media be “verbally or physically abused” and “under no circumstances whatsoever, may a member willfully damage the camera, film, recording or other equipment of a media representative.”

Yet despite high-level meetings between media and the police’s top brass, who say that such actions are not condoned, incidents continue to occur. The most recent meeting was in June this year between the South African National Editors’ Forum (SANEF) and the Johannesburg Metro Police after a photographer and TV cameraman were roughed up when they filmed officers arresting a drunk driver.

Incidents are happening so regularly that the Right2Know Campaign has published a booklet and cards explaining their rights for journalists to give to police if they are interfered with while on the job.

But, problematically, Standing Order 156 only deals with media and makes no mention of civilians who film the police using mobile phones.

“One shortcoming that we discovered in putting this together is that there isn’t enough protection for bystanders with cell phones,” says R2K spokesman Murray Hunter. “Under the Constitution, everyone has the same right to freedom of expression – working journalists and ordinary people alike. It’s especially important since bystanders with cell phones are often sources for mainstream media.

“But the direct orders that we refer to in this advisory only instruct police not to interfere with old-school media workers. So bystanders may still find themselves in a situation where the Constitution recognises their right to freedom of expression, but a police officer on the ground doesn’t.”

An example of the important role now played by citizens in newsgathering is the video footage shot by a bystander on a mobile phone of police brutalising taxi driver Mido Macia for an alleged minor parking offence. Sent anonymously to the Daily Sun newspaper, it led to the dismissal of nine policemen, who are now on trial for the killing of Macia.

One beacon of hope is that Standing Order 156 is under review after SANEF complained to the police about repeated media harassment. R2K sees this as an opportunity to include protection of the rights of citizen reporters, as well as media professionals, says Hunter.

But that could take time and involve protracted negotiations. And even if it happens there is no guarantee that police will heed the force’s own rules, or that the harassment of journalists and others will end.

It seems that the more things change, the more they will stay the same.

This column was posted on 6 August 2015 at indexoncensorship.org