22 May 2015 | Campaigns, Europe and Central Asia, mobile, Statements, United Kingdom

Britain’s Home Secretary, Theresa May, would — apparently — like to pre-approve programmes before broadcast that may include “extremist” content. We know this thanks to a leaked letter to the prime minister from the former Culture Secretary Sajid Javid who expressed his objection to the plans of his fellow cabinet minister.

Javid pointed out, quite rightly, that such a move could (and would) have a damaging effect on free speech — a freedom that David Cameron himself identified earlier this month as being part of the “British values” he wants to protect (values and freedoms that are systematically being attacked by the current government though proposed measures such as the Snoopers Charter and planned abolition of the Human Rights Act).

The world’s most repressive regimes largely have no need to pre-vet content. This is simply because they control all media outlets, and thus the messaging of the broadcasts and press. Why bother pre-vetting content when you’ve decided everything that goes out in the first place. If you can’t do that, pre-vetting is the next best step for an authoritarian government. China, which has one of the most sophisticated and far-reaching censorship regimes in the world, pre-censors TV documentaries, as well as non-fiction films, and has strict guidelines for broadcasters — including online companies — that forces them to self-censor huge swathes of content. Burma, whose military dictatorship finally ended in 2011, had pre-publication censorship for more than four decades.

As Javid himself notes in his letter: “It should be noted that other countries with a pre-transmission regulatory regime are not known for their compliance with rights relating to freedom of expression and government may not wish to be associated with such regimes.”

Yet with every step Theresa May makes she seems — under the guise of protecting our national security — to be bringing us closer and closer to the practices of countries who restrict the rights of their citizens to speak openly, countries who spy on their people indiscriminately, and countries who issue vague and obscure directives about the kinds of people and opinions deemed “unacceptable”.

We already have plenty of laws in Britain dealing with incitement to violence and the promotion of terrorism. We also have strict broadcasting rules addressing these areas. But the idea that the government should have a role in assessing content before it is broadcast, or in developing lists of speakers banned, not for inciting violence or hatred, but because their ideas are extreme, should set alarm bells ringing.

This article was posted on 22 May 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

23 Apr 2015 | Africa, Angola, mobile, News

Journalist and human rights activist Rafael Marques de Morais (Photo: Alex Brenner for Index on Censorship)

The trial of Rafael Marques de Morais, the investigative journalists who has exposed corruption and serious human rights violations connected to the diamond trade in his native Angola, will restart on 14 May. He was initially set to appear in court again on 23 April, but was informed of the postponement late in the evening on 22 April.

Marques de Morais is being sued for libel by a group of generals in connection to his work. The parties will be negotiating ahead of 14 May, to try and find some “common ground”, Marques de Morais told Index.

“In the interest of all parties and for the benefit of continuing work on human rights and for the future of the country, it is a very important step to be in direct contact,” he said.

“Rafael’s crucial investigations into human rights abuses in Angola should not be impeded by this dialogue. Index stresses the importance of avoiding any form of coercion,” said Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg.

Marques de Morais originally faced nine charges of defamation, but on his first court appearance on 23 March was handed down an additional 15 charges. The proceedings were marked by heavy police presence, and five people were arrested. This came just days after he was named joint winner of the 2015 Index Award for journalism.

The case is directly linked to Marques de Morais’ 2011 book Blood Diamonds: Torture and Corruption in Angola. In it, he recounted 500 cases of torture and 100 murders of villagers living near diamond mines, carried out by private security companies and military officials. He filed charges of crimes against humanity against seven generals, holding them morally responsible for atrocities committed. After his case was dropped by the prosecutions, the generals retaliated with a series of libel lawsuits in Angola and Portugal.

“Despite major differences, there is a willingness to talk that is far more important than sticking to individual positions. But this cannot impede work on human rights, freedom of the press and freedom of expression,” Marques de Morais added.

This article was posted on 23 April 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

27 Mar 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News, Serbia

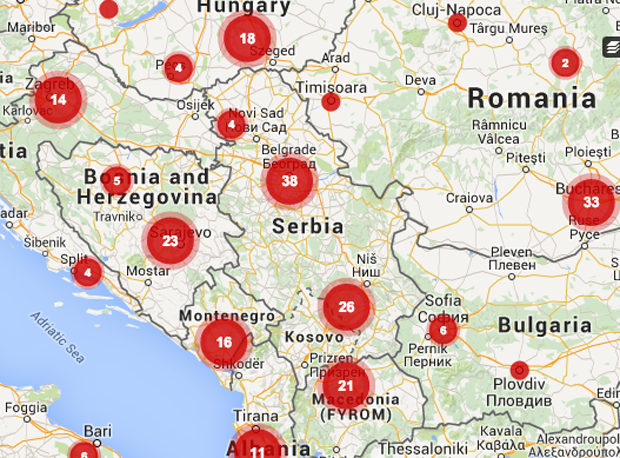

Working as a professional journalist in Serbia is hard. Being one in the country’s inland is even harder. Out of the 58 verified incidents involving Serbian media outlets and professionals reported to Index on Censorship’s European Union-funded Mapping Media Freedom, 30 have occurred outside Belgrade; the country’s political, economic and media capital. Four of these incidents have been directed at Juzne Vesti staff.

Launched in 2010 by journalist Predrag Blagojevic, Juzne Vesti is an independent news site based in Nis, a town of 257.000 in southern Serbia. In just over five years, its journalists have been subjected to verbal harassment or death threats 15 times. Though they have reported the incidents to local authorities, it has not resulted in convictions.

“Nobody has been found guilty and punished for the threats,” Blagojevic, who is also the site’s editor-in-chief, told Index.

According to Blagojevic, the main obstacle to punishing those threatening journalists comes from the prosecutor’s office. While he is quick to complement police in the town for their professional and timely investigations, he blames prosecutors for failing to act on the evidence by filing indictments quickly.

“In two situations from four to six months passed from the time the police filed a criminal charge to the prosecutor’s indictments,” Blagojevic explained.

Juzne Vesti correspondent Dragan Marinkovic from Leskovac received threats on Facebook after he published an article about the death of a woman, in which he questioned the treatment provided by a paramedic. He reported the incident to authorities. Several months later prosecutors decided not to pursue the case, arguing that “you deserve a bullet” is not a threat.

In March 2014 Blagojevic was threatened by the owner of a local football club, yet prosecutors waited until late September to indict the main suspect. The first court hearing was scheduled for December 2014; the next one at the end of this month.

While such delays are frustrating, once in court, judges have taken some dubious positions, Blagojevic said. In one case, the court said that “be careful what you write” or “do not play with fire” were not threats, but words that “merely showed the seriousness of the topic”. In another instance, where the perpetrator asked a Juzne Vesti staffer “Will you be alive in the morning if you wrote something like this in the USA?”, the court said that “the inductee, by placing the action in the foreign country, shows that he is aware that murder is prohibited by Serbian law”.

Outside the legal system, there is another obstacle to independent journalism in Serbia: money. While the Serbian government pays for advertising space, most of the earmarked money is directed at the national press. At the same time, the number of successful companies outside Belgrade and Novi Sad are few, and those that do thrive in the Serbian inland are usually aligned with local political figures. That leaves a tiny pool of advertisers.

“In these circumstances we are left with only very small companies, which are connected with political parties or dependent on municipal budgets. The game is straightforward — only if you are good to us you will get money,” Blagojevic said.

In an interview with SEEMO, Blagojevic described situations where certain media outlets have been financed with taxpayers’ money. With this line of funding, competing outlets are able to offer low rates that distort the advertising market, which puts pressure on independent media to drop their rates.

“The local government in Nis sets aside hundreds of millions of dinars in payment for these PR services,” Blagojevic said. The money is sometimes up to 80 per cent of the budget for these outlets making it even more difficult for independent media to compete.

The Council of Europe’s recent report on the Serbian media situation addressed the issue: “Instead of making efforts to create non-discriminatory conditions for media industry development, the state is blatantly undermining free market competition.”

The last issue confronting Juzne Vesti staff is one that will be familiar to small town journalists around the world — everyone knows everyone. Blagojevic tells of having to convince one journalist to file a complaint because she knew the person who had targeted her. She was reluctant because she had known the person “since they were kids”, he said.

From Blagojevic’s point of view, the toxic mix of money, political pressure and indifference from the courts causes self-censorship among journalists.

“The language from the 90s is back in Serbia. Again, journalists that criticise the work of the government or are reporting on corruption are labelled as foreign mercenaries. Threats like this come from the mouths of the highest state representatives,” he said.

An earlier version of this article stated that Nis has a population of 184,000. The latest census puts the figure at 257.000.

This article was posted on March 27, 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

6 Mar 2015 | Afghanistan, Asia and Pacific, mobile, News

Last year, authorities in the east of Afghanistan decided to shut down a cemetery. The problem was that this particular cemetery was not just a final resting place; it had taken on a second function as a marketplace where women in the city could meet and trade. With the closure, the financial lifeline the women had created for themselves, was cut. There were some protests, the story was covered in a local newspaper, and that was it.

Afghan media has experienced a significant growth spurt over the past years. In 2000, the country was home to 15 news outlets; in 2014 the figure was just shy of 1,000. Hidden within these numbers is another slowly expanding subcategory. Of around 12,000 working journalists in Afghanistan today, some 2,000–2,500 are women, up from an estimated 1,000 in 2006. The truly vital role these women play in Afghan society is too often overlooked.

In a country where traditional cultural norms still hold significant sway, strict limitations on contact between the sexes continue to be enforced in many areas. As a result, there are spaces only female journalists have access to, grievances only female journalists can be told and important realities of women’s lives that only female journalists can report on. Where women media workers are few and far between, such stories — like in the case of the cemetery closure — go underreported, or are buried entirely.

“Covering and focusing on women’s issues is always my favourite, and when I produce programs and make reports on these issues, I really like it and think I’ve done something important,” Radio Sahar Station Manager Humaira Habib told Index. Radio Sahar is part of Parwana (butterfly), a network of radio stations dotted around Afghanistan, which focuses on stories that impact women and their rights and needs. And from the managerial to the executive level, they are all-female operations.

Habib says she made the decision to go into journalism in 2002, and was influenced by the plight of women under the Taliban. “I thought journalism was a good tool to reach to all the aims and goals, and to solve the problems and challenges of women. I think media plays a very important role in informing citizens,” she explained. “This was the reason I decided to study journalism.”

But while the long view seems to suggest the number of Habib’s female compatriots will continue to grow, serious challenges and setbacks remain the reality in the shorter term.

Part of the problem is that the same traditional norms that make female journalist’s contribution especially valuable, still present a significant barrier to many women joining the media industry. As reporter Zarghona Salihi told Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, journalism is widely viewed as “immoral work” that carries with it social stigma for women.

“Parents don’t permit their daughters to become journalists [in particular] because female journalists soon turn popular and that puts them in lots of troubles,” news radio host Haseena Ahmadi told Voice of America.

Another, more direct and overt challenge is the seemingly worsening security situation for media workers in general, and the particular threats faced by women. Since 2001, 49 journalists have been killed, and attacks went up 64 per cent from 2013 to 2014, according to a recent report from Human Rights Watch. What’s more, they face a multi-pronged assault — from the government and local authorities, as well as from war lords and the Taliban. Meanwhile, impunity for such crimes persists.

Women must deal with all this, and then some. “Female journalists face particularly formidable challenges. Social and cultural restrictions limit their mobility in urban as well as rural areas, and increase their vulnerability to threats and attacks, including sexual violence,” the Human Rights Watch report states. Since 2010, three female journalists have been killed, including 26-year old Palwasha Tokhi, stabbed to death outside her house in September last year. The Afghan Journalists Safety Committee says that “dozens have been intimidated to stop working”. In 2013, Shaffiqa Habibi, director of the Afghan Women Journalist Union, estimated that 300 professional female journalists had stopped working due to safety concerns.

“The big challenge that journalists face here is the security problem. That really hurts us,” agrees Habib. In 2004 she was threatened by authorities and told she could never again work as a journalist in the western province of Herat. But she fought back, and today continues to hold a senior role at a radio station in that province. As one young journalist told International Media Support: “I have been threatened by the Taliban, corrupt authorities, warlords and even the government. But none of these threats will ever stop me from what I do.”

The struggle, however, doesn’t end by challenging traditions and braving a volatile security situation. Female journalists in Afghanistan are also facing a problem familiar to women all over the world: they’re simply not getting the chances their male counterparts are. On this point, international media has failed Afghanistan’s women reporters. While Amie Ferris-Rotman was working as Reuters’ Afghanistan correspondent, she realised that none of the foreign news outlets hired Afghan female correspondents, in any capacity.

“I found this hypocritical,” she told Index. “We put out a plethora of stories on women’s rights and the awful hurdles Afghan women face, yet we did not take the extra step to hear their stories in a professional context.”

Pointing to the continued prevalence of separation between the genders, she argues that by not giving a platform to female Afghan journalists, we are missing the full story. The journalists, meanwhile, are denied good networks and professional opportunities to further their careers. To help rectify this situation, Ferris-Rotman has set up the Sahar Speaks programme, to offer training and mentoring by peers from around the world to Afghan female journalists, with the aim of helping them produce stories to be published by international outlets. As she has written about the project: “Imagine how rich and nuanced the other side of the Afghan story can be, if told by its own women, not by Afghan men or foreign reporters.”

Abdul Mujeeb Khalvatgar, the director of media freedom advocacy group Nai, which is behind the Parwana network, believes it to be very important that Afghanistan’s female reporter pool continues to grow. Certain topics, he explains, are still considered by some to be taboo for men to cover. He mentions literacy rates among women, violations against women and how women are treated both in rural and urban areas as examples of stories that “raised the need of having women journalists to report”.

Habib stresses the importance of increasing the number of female reporters outside the bigger cities, where many women’s issues that male journalists have limited access to, go uncovered. This is a “serious problem” she says, adding that “we need to train girls from those places to at least learn basic journalism to cooperate with local and national media”.

Despite the challenges, Khalvatgar, who has been nominated for an Index award for his media freedom campaigning in Afghanistan, is confident that there is enthusiasm among women to work in the sector. He points to his experience of visiting journalism schools and seeing a higher number of female than male students, as one indicator. “There are a lot of hopes and wishes among women to become journalists,” he says.

Afghanistan’s President Ashraf Ghani vowed during his 2014 election campaign to uphold freedom of expression and protect journalists against abuse. Whether he will stick to his promise down the line, so the enthusiasm Khalvatgar speaks about can truly be harnessed, remains to be seen. What is clear, is that without more women feeling encouraged and safe enough to join Habib and her colleagues in their work, important stories will continue to go untold.

This article was posted on March 6, 2015 at indexoncensorship.org