20 Feb 2015 | Egypt, Middle East and North Africa, News

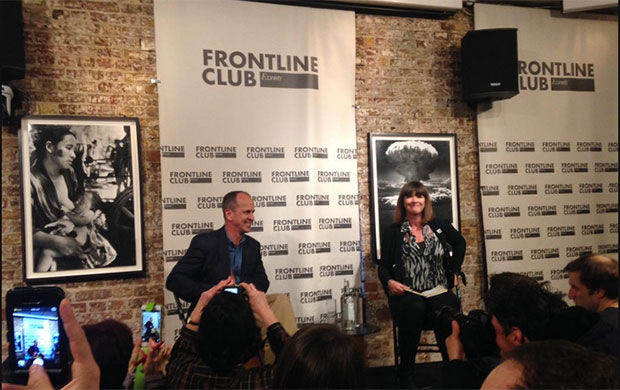

Peter Greste spoke to a Frontline Club audience about his arrest and detention in Egypt. (Photo: Milana Knezevic / Index on Censorship)

Peter Greste, the Al Jazeera journalist recently released after 400 days in Egyptian jail, met a packed room at London’s Frontline Club on Thursday, where he spoke about his time in jail, the campaign for his release and fellow journalists still imprisoned in Egypt. “An attack on journalism, an attack on freedom of speech, is an attack on the wider society,” he said.

“I remember that day well,” he said, recounting 29 December 2013, when a group of around eight men came to his Cairo hotel room and without explanation started searching it, before talking him away. While he was aware that the media was under some pressure in Egypt, the arrest came as a surprise. He felt as long as they stuck to their journalistic principles and didn’t push boundaries, they would be fine.

“There have been plenty of stories before where I’ve pushed boundaries, when I fully expected to get a knock on the door from the police, when I know I’ve upset governments,” he explained. But this time around, he hadn’t gone looking for difficult stories or made a conscious effort to try and challenge the government, so he “genuinely didn’t think it was going to be an issue.”

Greste was imprisoned together with Al Jazeera producer Baher Mohamed and Al Jazeera English’s Cairo bureau chief Mohamed Fahmy. He said they forced themselves to consider that they might be convicted, but never seriously believed it.

While there were “some very dark moments”, he insisted anger wasn’t his dominant emotion, believing that letting anger take hold of the situation would only hurt himself. They were broadly treated with respect in prison, and never physically threatened. “The problem is that in prison…what really matters is your own head, your own mind and how you cope with it.”

Egypt

Index has reported extensively on the situation confronting free expression in the country

Committee to Protect Journalists named Egypt as one of the world’s top 10 jailers of journalists in Dec 2014

Reporters Without Borders: World Press Freedom Index ranks the country as 159

Freedom House: Classifies Egypt as “not free”

Greste spoke of the importance of having a routine and some structure to his day, crediting seemingly simple things like meditation, exercise, studying and even cooking with helping him though the ordeal.

“The only way through is to set your horizon, to set a target date, to set something that’s manageable,” he said. “What you do is narrow your horizon, to the thing that you think you can cope with. Sometimes that was the end of next week, or it would be to the next visit. Sometimes it would be simply to the end of the day.”

Today, he doesn’t feel traumatised, and believes that we are all more capable of dealing with difficult situations than we think. And when discussing the conditions in prison, it was clear he had kept his humour. “The less said about the toilets the better,” he joked.

If his detention had been a surprise, so was his release. He had been expecting his brother for a visit, when he got the unexpected message to pack his bags — he was going home. Himself, Fahmy and Mohamed had discussed the possibility that one of them might be released before the others, and all agreed that if that were to happen, there would be no doubt that that person should go.

And yet, Greste said walking away and leaving Mohamed and others (Fahmy was receiving medical treatment at the time) behind was not easy. “And I still feel that and I still feel quite anguished about it.” His two colleagues have now been released on bail, with their retrial set to start on Monday.

Greste was also keen to remind us that while the three of them had been given the most media attention, many others had been caught up in the case — including three young students, a businessman and journalists sentenced in absentia.

“We can’t forget that sympathy tends to go with people who you identify with. As a European, as a white guy, it’s easier for white Europeans to identify with me than it is to identify with an Egyptian. I’m not suggesting for a second that that makes Baher’s case any less worthy. And in a way we need to bear that in mind, that because of that trend, it’s so easy to let local journalists slip through the cracks,” he also added. “It is the locals that get hit, and the freelancers in particular.”

He said he’ll continue to report, though he is not yet sure what form his work will take. He also hopes to continue to speak out for press freedom.

“One of the most extraordinary elements of this, and one that we are in danger of losing, if we do not make a conscious effort to hold on to, is the unity of purpose that emerged within the media community around our case. For some reason, the community right across the globe pulled together in a way that I think is absolutely unprecedented; we’ve never seen anything like this ever before,” he said.

“If we lose that sense of purpose, then we lose something that we have created of enormous value. I think its very difficult to maintain, particularly under the current circumstances, but I think it’s incumbent on everybody to recognise it, to make use of it, not just in our case but in the case of every journalist that’s been imprisoned.”

This article was posted on 20 February 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

27 Jan 2015 | About Index, Awards, mobile

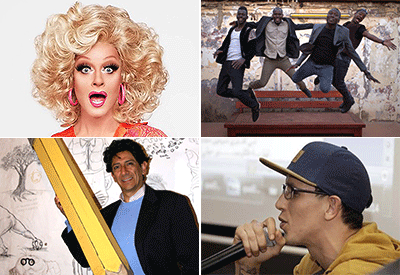

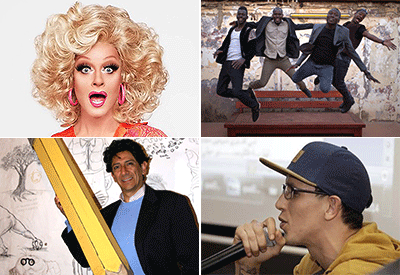

From top left: Xavier “Bonil” Bonilla, Safa Al Ahmad, Mouad “El Haqed” Belghouat and Lirio Abbate are among the Index Freedom of Expression Awards nominees for 2015.

A journalist under 24-hour protection because of his reports into the Italian mafia, an Ecuadorian cartoonist facing prosecution for mocking a congressmen’s pay packet, and lawyers who challenged Turkey – and won – over its social media ban, are among those shortlisted for the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards this year.

Drawn from more than 2,000 nominations, the shortlist celebrates those at the forefront of tackling censorship and threats to freedom of expression. Many of the 17 shortlisted nominees are regularly targeted by authorities or by criminal and extremist groups for their work: some face regular death threats, others criminal prosecution.

“The Index Freedom of Expression Awards recognise some of the world’s most courageous journalists, artists and campaigners,” said Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index. “These individuals and groups often work in isolation, with little funding or support, but they are all driven by the vision of a world in which everyone can express themselves freely – no matter who they are or what they believe.”

Awards are offered in four categories: journalism, arts, campaigning and digital activism.

Those on the shortlist include Lirio Abbate, an Italian journalist whose investigations into the mafia mean he requires constant protection; Safa Al Ahmad, whose documentary exposed details of an unreported mass uprising in Saudi Arabia; radio station Echo of Moscow, one of Russia’s last remaining independent media outlets; and Rafael Marques de Morais, an Angolan reporter repeatedly prosecuted for his work exposing government and industry corruption.

Arts nominees include Ecuador’s censored cartoonist Xavier “Bonil” Bonilla – who has for more than 30 years critiqued and lampooned the country’s authorities; Moroccan rapper Mouad “El Haqed” Belghouat, whose music challenges poverty and government corruption; Rory “Panti Bliss” O’Neill, a Dublin-based drag artist who speaks out against homophobia; and Malian musicians Songhoy Blues, who fled their country after music was banned. Guitarist Garba Touré was threatened with having his hand cut off.

In the campaigning category, nominees range from lawyers Yaman Akdeniz and Kerem Altiparmak, who played a key part in overturning Turkey’s social media ban last year; to innovative German anti-Nazi group ZDK; to Amran Abdundi, working on the treacherous Somali-Kenya border to help women and girls who are frequently victims of violence, rape and murder. They also include Abdul Mujeeb Khalvatgar who is working to develop a free media in Afghanistan, and The Union of the Committee of Soliders’ Mothers of Russia – a group dedicated to exposing stories of Russian soldiers, killed in the Ukraine conflict, which the Russian government denies.

The digital activism category, which is decided by public vote, includes investigative news outlet Atlatszo.hu, which is using freedom of information requests to hold the Hungarian government to account; Nico Sell, a US-based entrepreneur and online privacy activist; online map Syria Tracker, which is providing reliable data on human rights abuses in Syria; and Valor por Tamalipas, a crowd-sourced news platform set up to fill a void created by the region’s drug cartel-induced media blackout.

The shortlisted nominees:

Arts

Panti Bliss (Ireland)

Songhoy Blues (Mali)

“Bonil” (Ecuador)

“El Haqed” (Morocco)

More details

Campaigning

Amran Abdundi (Kenya/Somalia)

Zentrum Demokratische Kultur (Germany)

Abdul Mujeeb Khalvatgar (Afghanistan)

Yaman Akdeniz and Kerem Altiparmak (Turkey)

Soldiers’ Mothers (Russia)

More details

Digital Activism

Syria Tracker (Syria)

Nico Sell (USA)

Atlatszo.hu and Tamás Bodoky (Hungary)

Valor por Tamaulipas (Mexico)

More details

Journalism

Rafael Marques de Morais (Angola)

Safa Al Ahmad (Saudi Arabia)

Lirio Abbate (Italy)

Echo of Moscow (Russia)

More details

This article was posted on 27 January 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

5 Dec 2014 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan News, News

Khadija Ismayilova

The arrest of Azerbaijani investigative journalist Khadija Ismayilova today underscores the entrenched authoritarian instincts of the government of President Ilham Aliyev. Ismayilova was sentenced to a two month pretrial detention.

“The arrest of Khadija Ismayilova is part of Azerbaijan’s continued crackdown on free media and civil society. This confirms the pattern of intimidation and harassment perpetrated by authorities in an attempt to silence critical voices,” Melody Patry, senior advocacy officer at Index on Censorship, said.

Ismayilova’s arrest follows the earlier detentions of human rights defenders Leyla Yunus and her husband Arif Yunus; free speech advocate Rasul Jafarov; journalists Seymur Hezi, Parviz Hashimli, Nijat Aliyev and Sardar Alibeyli; and bloggers Omar Mamedov, Abdul Abilov and Rashad Ramazano. The country has starved the 2014 Index award winning Azadliq newspaper of resources, forcing it to suspend its print edition. The charges against all of the detainees range from hooliganism to illegal storage and sale of drugs.

Today’s action by Azerbaijan’s authorities also drew immediate criticism from Human Rights House Foundation Executive Director Maria Dahle and the OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media Dunja Mijatović.

“This sentence does not come as a surprise: we assumed the authorities wanted to silence Khadija Ismayilova,” said Dahle. “The arrest has a chilling effect: one must now consider that every independent civil society leader in Azerbaijan is a target and can be arrested at any given time for any charge, as ludicrous as one can imagine. The international community, especially the Council of Europe, must now get a foot in the door to stop the repression, including by stopping further cooperation with Azerbaijan’s authorities”, Dahle added.

“The arrest of Ismayilova is nothing but orchestrated intimidation, which is a part of the ongoing campaign aimed at silencing her free and critical voice,” Mijatović said.

On Friday afternoon, Ismayilova’s usually very active Facebook page was also inaccessible.

Azerbaijan, which spends significant amounts on media relations, presents itself as a modern nation. But behind the smokescreen, the country has been carrying out a systematic suppression of civil society, journalists and independent media.

This article was posted on 5 Dec 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

24 Nov 2014 | Egypt, News, Politics and Society

Egyptian President Abdel Fattah El Sisi has tightened the screws of the country’s journalists. (Photo: Wikipedia)

In a rare show of defiance, hundreds of Egyptian journalists have objected to a “statement of allegiance” to the government signed by editors-in-chief of the main state-owned and independent newspapers.

More than 600 Egyptian journalists signed an online petition defending press freedom and rejecting censorship in all its forms. The move came in response to a loyalty pledge by 17 editors-in-chief of newspapers to refrain from criticizing the police, the military and the judiciary at this sensitive time when Egypt was “at war with terrorism.”

The journalists dismissed the editors’ statement as “a futile attempt to create a one-voice media,” arguing that “fighting terrorism had nothing to do with voluntary abandonment of freedom of speech.”

“The editors’ statement is not worth the ink used in writing it,” Dina Samak, deputy editor-in-chief of the English language semi-official Ahram Online and one of the journalists who signed the petition, told Index on Censorship.

“The terrorists will win when they can control the media, and the state will fall when it agrees on the same goal,” said Khaled El Balshi, a journalist and board member of the Journalists Syndicate, who helped draw up the petition for press freedom.

In a show of solidarity with Egypt’s military-backed regime, the editors had gathered at El Wafd newspaper headquarters on 26 October to forge “a united front against terrorism”, expressing their “rejection of attempts to cast doubt on state institutions.” They also vowed to take measures to halt what they called the “infiltration by elements supporting terrorism” in their publications — a reference to supporters of the outlawed Muslim Brotherhood, designated as a terrorist group by Egypt last year.

While the move did not come as a surprise to many — as it was already clear that the majority of media outlets had aligned themselves closely with the government since the military takeover of the country in July 2013 — the “loyalty pledge” by the editors was nevertheless unusual even in a country where the media was in lockstep with the regime.

The signatories to the declaration — the editors-in-chief of the three main state-owned dailies Al Ahram, Al Akhbar, Al Gomhouria and those of the independent Al Masry Al Youm, Al Watan, Al Shorouq, El Tahrir, El Ahali, Al Fajr , El Messa, El Esboo, El Youm el Sabe and El Gamaheer newspapers — argued however that “crisis situations” required “exceptional measures”.

Defending the editors’ statement, Emad El Din, editor-in-chief of the independent Al Shorouk denied that the editors’ loyalty declaration gave journalists the green light to practice self censorship.

“We wanted to deliver a message to citizens that the media is with the state in fighting terrorism,” he told NPR Radio shortly after signing the statement.

“At this time of heightened nationalism, the climate does not allow for any criticism of the government,” he added.

The move came in response to a call by President Abdel Fattah El Sisi for Egyptians to rally behind him in his fight against terrorism following two deadly militant attacks on an army checkpoint in North Sinai on 24 October that killed 33 army soldiers and injured at least a dozen others. The militant assaults were the latest in a string of attacks targeting mainly security forces — but at times, also civilians — since the overthrow of Islamist President Mohamed Morsi in July 2013. The attacks have prompted a surge in nationalism and a heralding of a so-called “war on terrorism” waged by the military against suspect-militants in the Sinai Peninsula. The violence has also resulted in a massive government crackdown on dissent that has targeted all opposition including journalists critical of regime policies.

Six journalists have been killed and dozens detained since the military took power in July 2013, according to the New York-based Committee for the Protection of Journalists. While most have been released, at least 11 journalists remain behind bars for no crime other than being at — or near — Muslim Brotherhood protest sites. Among the detained are three journalists working for the Al Jazeera English news network who have been sentenced to between seven and 10 years in jail on charges of “threatening national security, fabricating news and aiding a terror group”.

The crackdown on the media has led many journalists to practice self-censorship for fear of being imprisoned, killed or labeled “unpatriotic” by an unsympathising Egyptian public. Meanwhile, the statement released by the editors has fueled fears among press freedom advocates of a further shrinking in the already-dwindling space for freedom of expression in Egypt.

Adel Hamouda, an Egyptian journalist and former editor-in-chief of Al Fajr, meanwhile, criticised the editors’ statement as “uncalled for“.

“It is an attempt by the editors to win favour with the regime for the sake of personal gains,” he told Index. He explained that all Egyptians — except those supporting the Muslim Brotherhood — support the state in its war on terror so it is “meaningless” to publicly assert their support. He further noted that all media organisations were required to seek approval from the Armed Forces Morale Affairs Department before publishing or broadcasting any news about the military.

The majority of the independent media outlets that signed the statement belong to wealthy businessmen with close links to the ruling military-backed regime. They are fully aware that publishing any criticism of government policies would ruffle feathers and likely jeopardize their business interests. All top editors were appointed by the Higher Press Council shortly after Morsi’s overthrow in July 2013. Their selection was clearly based on their willingness to cooperate with the regime rather than their merits. Shortly after Morsi’s ouster, a leaked video on YouTube showed then-Defence Minister Abdel Fattah El Sisi asking senior generals to “establish partnerships with media outlets to curb any criticism of the military”. An independent journalist who spoke on condition of anonymity told Index that days before Morsi’s ouster, she had been approached by security officials who promised her “fruitful rewards” if she joined the “winning side” — a clear reference to the country’s powerful security apparatus that drove the uprising against the democratically-elected president.

In the coup’s aftermath, most editors and TV talk show hosts have persistently lionised Sisi and cheered on the military while demonising the Muslim Brotherhood, the Islamist group from which former President Mohamed Morsi hailed.

The media in Egypt has traditionally been a propaganda tool for whoever is in power. Various successive regimes have used the state media as a mouthpiece to further their political gains. Under Mubarak, all editors-in-chief of the state-owned newspapers were handpicked by his powerful Minister of Information Safwat El Sherif who presented the list of chosen candidates to the Shoura or Consultative Council, the upper house of parliament dominated by members of the then-ruling party, the National Democratic Party, for ratification.

In the months following the fall of Mubarak, there was a brief period of free expression and a loosening up of restrictions on the media. Press freedom — one of the major gains of the 2011 mass uprising — was short-lived however as the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) which replaced Mubarak, quickly moved to exercise control over the media. During its one year in office, the SCAF confiscated newspapers, ransacked the offices of foreign news networks and investigated journalists critical of the military. Shortly after Morsi won the elections — becoming the country’s first democratically elected president — he too reneged on his election promises to promote freedom of speech, appointing a Muslim Brotherhood member as minister of information. The Muslim Brotherhood-dominated Shoura appointed regime loyalists as senior editors of state-owned dailies, repeating the Mubarak-era practice that allows tight government control over the media. The move provoked an outcry from non-Islamist journalists who held protest rallies and threatened to resign their posts.

Almost immediately after Morsi’s overthrow, all Islamist-leaning newspapers and TV channels were shut down by the new authorities — a move that sent a message to journalists that there was little tolerance for dissent in Egypt, post-3 July. The last sixteen months have seen a return of the media censorship reminiscent of that which prevailed under Mubarak. Newspapers that published articles deemed “controversial” by the authorities, have been pulled off newsstands and confiscated. In October 2014, a print edition of the independent Al Masry Al Youm was confiscated by government censors for publishing an interview with former national security intelligence chief Mohamed Gebril in which he was quoted as saying that “no Israeli spy has ever been executed in Egypt”. The paper later appeared on newsstands, albeit without the interview. Months earlier, columnist and screenwriter Belal Fadl resigned from the independent Al Shorouk after the paper’s management allegedly refused to publish his column ridiculing the promotion of Sisi (who was defence minister at the time) to the rank of field marshal. Fadl was accused by pro-military commentators of being a “traitor” and “a fifth columnist plotting to destroy the country”.

Several editors who signed the statement of support to the government are also known to be part of a fake opposition created by Mubarak to give a semblance of free speech and democracy. Like other pro-regime editors, they too have persistently glorified the military and vilified the Muslim Brotherhood. And they have gone a step further, slandering the January 25 Revolution as a “foreign conspiracy” and labelling the secular opposition activists who mobilised public support for the 2011 mass protests “traitors” and “foreign agents.”

Mostafa Bakri, editor-in-chief of Al Osbou — and one of the editors who signed the loyalty pledge — has recently been summoned by the public prosecutor after several legal complaints were filed against him by private citizens for “fabricating news” and “slandering the January 25 Revolution”.

Meanwhile, the journalists behind the online petition for press freedom are planning to form an independent association to advocate freedom of expression. While this is a step in the right direction, press freedom advocates fear the negative effects of the editors’ pledge of allegiance are already being felt.

“Their statement was perceived as a warning message by the younger, less skilled journalists, many of whom are now practicing self-censorship for fear of losing their jobs or in a bid to win favour with the management and get promoted,” lamented Dina Samak.

Despite the setback, the battle for press freedom is on.

“It is a battle pitting the younger, pro-reform journalists against the old regime loyalists, resisting change,” Amany Kamal, a former radio presenter told Index. Kamal was forced to quit her job as a broadcaster with a state-run radio channel after being accused by the management of sympathising with the Muslim Brotherhood. “But we shall win,” she said.

This article was published on 24 November 2014 at indexoncensorship.org