21 Nov 2014 | Azerbaijan News, News, Politics and Society

Impunity is a festering sore on freedom of the press. Harassment, violence and murder of journalists are problems around the world — even in Europe, as Index’s project mapping media violations has shown. The numbers speak for themselves: of the 370 media workers murdered in connection with their job over the past ten years, 90% have been murdered without their killers being punished. Many of these crimes aren’t even investigated.

Ahead of the International Day to End Impunity, journalists from across the world told Index why impunity is such a danger to free expression and a free press.

Kostas Vaxevanis, Greek investigative journalist, HOT DOC, and 2013 Index award winner

Impunity generates corruption and its enemy is the one thing that exposes and threatens it: the freedom of the press.

The HOT DOC is currently facing 40 lawsuits mainly from ministers and politicians in an attempt to shut us down as journalists. We reveal scandals like one with the minister of justice, a former judge who committed an “error” that granted amnesty to officials who had abused public funds, and instead of answering in public as required as politicians, we are being sued. We pester the courts and despite winning lawsuits, we need more than 80,000 euro per year for court expenses.

Heather Brooke, British-American journalist and 2010 Index award winner

It is a problem that journalists around the world get threatened, intimidated and killed just for doing their job.

These crimes, like any other crime, need to be investigated. If not, it sends a message that this is okay; that the law is only for certain people. It is an implicit acceptance of this behaviour.

If we want to have a strong press, threats, intimidation and murder of journalists can’t be seen to be implicitly condoned by the state. It’s a dangerous message. It makes people frightened to ask tough questions, and if that happens, you are on the way to shutting down a robust press.

Kareem Amer, Egyptian blogger and 2007 Index award winner

I come from a country where we have a lack of justice. The executive power controls the parliament and the justice system. People feel that if they get mistreated or oppressed by those in power nothing will protect them or bring them justice.

Not only people who express their opinions suffer from a lack of justice. People from different backgrounds who have a different way of thinking and different interests also don’t trust the justice system. Those who have more power can easily avoid punishment and take revenge against victims who tried to get their rights through judiciary system.

Officially, police officers don’t have any kind of formal immunity. According to the law they can be questioned if they violate the rights of people by torturing or murdering. But, in fact, all those accused of killing protesters and torturing prisoners managed to avoid being punished, with a few exceptions.

I feel that it’s not safe to express your opinions freely in a country where people can easily avoid punishment.

I have been sentenced to four years in jail for writing two articles and publishing them on the internet, and during that time I have been through physical violence and mistreatment committed by security forces. I reported it but no one has been questioned or punished. That made me feel that there is no justice in my country and that it is easy to be humiliated and tortured and you will not get protected, since the judiciary system is practically part of the executive power and the judges do what the authorities want them to do.

Rahim Haciyev, Azerbajiani journalist and acting editor of 2014 Index award winner Azadliq

Rahim Haciyev, deputy editor-in-chief of Azerbaijani newspaper Azadliq (Photo: Alex Brenner for Index on Censorship)

Freedom of expression is the basis of all other rights and freedoms. Free speech is something all authoritarian regimes are worried about as it threatens their existence. That is why freedom of expression is specifically targeted by authoritarian regimes. If there are no free people, there is no freedom of expression. Free speech is a precondition for journalists to be able to work in full strength and thus fulfill their functions in society. Authoritarian regimes organise permanent attacks on journalists with impunity. A free journalist armed with freedom of expression is a threat to an authoritarian regime, this is why perpetrators receive awards, not punishment for oppressing journalists’ rights. This process leads to self-censorship, and journalists stop being carriers of truthful information, which in the end affects society.

Nazeeha Saeed, award-winning Bahraini journalist, who was tortured in police custody

Impunity is a threat to free expression because journalists and people who report the facts on the ground will feel danger, and if no one gets punished for crimes against journalists or others it establishes a systematic impunity culture. Feeling insecure is something bad, it stops people from having a normal life, functioning and expressing themselves.

Endalk Chala, Ethiopian blogger and co-founder of the Zone9 blogging collective (of which six members are currently imprisoned for their writing)

Impunity is a threat for free expression on many levels. In my experience I have seen impunity when it cultivates self-censorship. Let’s take the case of Zone9 bloggers. Since their arrest there are a lot of people who tried to visit them in prison, take a picture of them, attend their trial and tweet about their hearings but all of these have invited very bad reactions from the Ethiopian police.

Some were arrested briefly, others were beaten and it has become impossible to attend the “trial” of the bloggers and journalists. No action was taken by the Ethiopian courts against the bad actions of the police even though the bloggers have contentiously reported the kinds of harassment. As a result, people have stopped tweeting, taking pictures and writing about the bloggers. Apparently, the volume of the tweets and Facebook status updates which comes from Ethiopia has dwindled significantly. People don’t want to risk harassment because of a single tweet or a picture. This self-censorship could be attributed to impunity, which is pervasive in Ethiopia.

Impunity also causes a lack of trust in the Ethiopian judicial system. I don’t trust the independence of the Ethiopian justice system. I have never seen a police man/woman or a government authority being prosecuted for their bad actions against journalists. The Ethiopian government has been prosecuting hundreds of journalists for criminal defamation, terrorism and inciting violence but not a single government person for violating journalists’ rights. This tells you a lot about the compromised justice system of the country.

Andrei Soldatov, Russian investigative journalist and co-founder and editor of Agentura.Ru

Russia is known for its traditions of self-censorship. Despite what the laws say, the rules are explained in a quiet voice in some unmarked cabinets. Sometimes the rules are even not explained, and journalists, editors and owners of media have to constantly guess what is allowed at that moment. Not everyone is allowed to ask directly, so we are all in the game about signals sent by the authorities.

Journalists are beaten and killed in Russia, and this provides plenty of room to send such signals to the journalistic community. You don’t need to explain that investigative reporting in the North Caucasus is not allowed anymore: you just need to turn the investigation of Anna Politkovskaya’s assassination in 2006 into a show trial, where the assassins are duly found guilty, but the question of masterminds is never answered. You could be sure, the signal would be taken correctly.

Fergal Keane, Irish journalist, BBC foreign correspondent and 2003 Index award winner

Impunity allows the enemies of free speech to threaten, torture and kill journalists secure in the knowledge they will never be called to account. I can’t think of a greater threat.

Veran Matic, B92 board of directors chairman and B92 news editor-in-chief

In my 25 years of experience in Serbia, I have been editor-in-chief of a media outlet that was banned on several occasions and I have been arrested.

Impunity directly encourages and expands violence towards journalists. The culture of producing fear is the most efficient form of censorship. One unsolved murder creates space for implementing the next one without any threat for the executioners. In the meantime, the media gets killed/eliminated in the process.

The lack of discontinuity with Slobodan Milosevic’s authoritarian regime had left room for impunity to remain intact.

Less than two years ago, I decided to make a kind of a breakthrough when it comes to impunity. I proposed the establishment of a mixed commission composed of journalists, members of the police and members of the security information agency. We managed to bring the 1999 murder of Slavko Curuvija to a phase where official indictment was brought, along with arrest of all suspects in this murder case. The 2001 murder of our colleague Milan Pantic is also in the final stage of investigation. A 1994 assassination — of Dada Vujasinovic — is being reviewed by the National Forensic Institute from The Hague because local institutions have compromised themselves in this case.

In the same way as impunity restricts freedom of speech, solving of these cases, at least 20 years later, will surely contribute to journalists being encouraged to do their job in the best possible way. Of course, I am not counting here on the new problems with which journalists and media face, and that call for finding new models of financing high quality journalism for the sake of public interest, worldwide.

The team behind Pao-Pao, a Chinese website focusing on internet freedom issues

This year, we have seen a rising number of Chinese journalists, academics and human rights lawyers detained, threatened and arrested simply for speaking out online. While Chinese regulations on freedom of speech need to be closely examined, tech companies also play an important role in the deterioration of freedom of speech in China.

While Chinese tech companies are under the tight control of the Chinese authorities, there exists a culture of impunity in the western tech companies, especially when they are doing business in China. When we worked with our partner GreatFire to launch a FreeWeibo iOS application last year (an app to deliver uncensored content from Weibo, the largest social media platform in China), Apple decided to remove the app from their Chinese iTunes store. The only reason given was that Apple received a request from the Chinese authorities. This June, LinkedIn censored user posts deemed sensitive by the Chinese government on the global level, far beyond Beijing’s censorship requirement, even though LinkedIn does not have servers in China.

It would be the start of the end if these global tech companies start removing content simply because they do not want to upset their business relationships with China. It is crucial to hold these companies accountable for their behaviour. Otherwise it will further erode freedom of expression, not only for China, but also for the whole world.

The International Day to End Impunity was set up in 2011 by free speech network IFEX, of which Index on Censorship is a member, with the aim of demanding accountability and justice on behalf of those “targeted for exercising their right to freedom of expression”.

This article was originally posted on 21 November 2014 at indexoncensorship.org. It was updated at 14:09, 24 November to include the response from Pao-Pao.

2 Nov 2014 | Campaigns, Russia, Statements

Aleksandr Bastrykin

Head of the Investigative Committee of Russian Federation

The Investigative Committee of Russian Federation

105005, Russia, Moscow, Technicheskii Lane, 2

Sunday 2 November 2014

Dear Mr Bastrykin,

RE: Request for investigation into the murder of Akhmednabi Akhmednabiyev to be transferred to the Central Investigative Department of the Russian Federation’s Investigative Committee.

On the International Day to End Impunity for Crimes against Journalists (2 November) we, the undersigned organisations, are calling upon you, in your position as Head of the Investigative Committee of the Russian Federation, to help end the cycle of impunity for attacks on those who exercise their right to free expression in Russia.

We are deeply concerned regarding the failure of the Russian authorities to protect journalists in violation of international human rights standards and Russian law. We are highlighting the case of Ahkmednabi Akhmednabiyev, a Russian independent journalist who was shot dead in July 2013 as he left for work in Makhachkala, Dagestan. In his work as deputy editor of independent newspaper Novoye Delo, and a reporter for online news portal Caucasian Knot, Akhmednabiyev, 51, had actively reported on human rights violations against Muslims by the police and Russian army.

His death came six months after a previous assassination attempt carried out in a similar manner in January 2013. That attempt was wrongly logged by the police as property damage, and was only reclassified after the journalist’s death. This shows a shameful failure to investigate the motive behind the attack and prevent further attacks, despite a request from Akhmednabiyev for protection. The journalist had faced previous threats, including in 2009, when his name was on a hit-list circulating in Makhachkala, which also featured Khadjimurad Kamalov, who was gunned down in December 2011. The government’s failure to address these threats is a breach of the State’s “positive obligation” to protect an individual’s freedom of expression against attacks, as defined by European Court of Human Rights case law (Dink v. Turkey).

A year after Akhmednabiyev’s killing, with neither the perpetrators nor instigators identified, the investigation was suspended in July 2014. As well as ensuring impunity for his murder, such action sets a terrible precedent for future investigations into attacks on journalists in Russia. ARTICLE 19 joined the campaign to have his case reopened, and made a call for the Russian authorities to act during the United Nations Human Rights Council (HRC) session in September 2014. During the session, HRC members, including Russia, adopted a resolution on safety of journalists and ending impunity. States are now required to take a number of measures aimed at ending impunity for violence against journalists, including “ensuring impartial, speedy, thorough, independent and effective investigations, which seek to bring to justice the masterminds behind attacks”.

While the Dagestani branch of the Investigative Committee has now reopened the case, as of September 2014, more needs to be done in order to ensure impartial, independent and effective investigation. We are therefore calling on you to raise Akhmednabiyev’s case to the Office for the investigation of particularly important cases involving crimes against persons and public safety, under the Central Investigative Department of the Russian Federation’s Investigative Committee.

Sadly, Akhmednabiyev’s case is only one of many where impunity for murder remains. The investigations into the murders of journalists Khadjimurad Kamalov (2011), Natalia Estemirova (2009) and Mikhail Beketov (who died in 2013, from injuries sustained in a violent attack in 2008), amongst others have stalled. The failure to bring both the perpetrators and instigators of these attacks to justice is contributing to a climate of impunity in the country, and poses a serious threat to freedom of expression.

Cases of violence against journalists must be investigated in an independent, speedy and effective manner and those at risk provided with immediate protection.

Yours Sincerely,

ARTICLE 19

Amnesty International

Albanian Media Institute

Association of Independent Electronic Media (Serbia)

Azerbaijan Human Rights Centre

Center for Civil Liberties (Ukraine)

Center for National and International Studies (Azerbaijan)

Civic Assistance Committee (Russia)

Civil Society and Freedom of Speech Initiative Center for the Caucasus

Committee to Protect Journalists

Glasnost Defence Foundation (Russia)

Helsinki Citizens’ Assembly – Vanadzor (Armenia)

Helsinki Committee of Armenia

Human Rights House Foundation

Human Rights Monitoring Institute (Lithuania)

Human Rights Movement “Bir Duino-Kyrgyzstan”

Memorial (Russia)

Moscow Helsinki Group

Norwegian Helsinki Committee

Index on Censorship

International Partnership for Human Rights

International Press Institute

International Youth Human Rights Movement

IREX Europe

Kazakhstan International Bureau for Human Rights and Rule of Law

Kharkiv Regional Foundation – Public Alternative (Ukraine)

PEN International

Public Verdict Foundation (Russia)

Reporters without Borders

The Kosova Rehabilitation Center for Torture Victims

World Press Freedom Committee

cc.

President of the Russian Federation

Vladimir Putin

23, Ilyinka Street, Moscow, 103132, Russia

Prosecutor General of the Russian Federation

Yury Chaika

125993, GSP-3, Moscow, Russia

st. B.Dmitrovka 15a

Minister of Justice of the Russian Federation

Alexander Konovalov

Ministry of Justice of the Russian Federation

119991, GSP-1, Moscow, street Zhitnyaya, 14

Chairman of the Presidential Council for Civil Society and Human Rights

Mikhail Fedotov

103132, Russia, Moscow

Staraya Square, Building 4

Head of the Investigative Committee of the Russian Federation for the Republic of Dagestan

Edward Kaburneev

The Investigative Committee of the Russian Federation for the Republic of Dagestan

367015, Republic of Dagestan, Makhachkala,

Prospekt Imam Shamil, 70 A

Ambassador of the Permanent Delegation of the Russian Federation to UNESCO

H. E. Mrs Eleonora Mitrofanova

UNESCO House

Office MS1.23

1, rue Miollis 75732 Paris Cedex 15

29 Oct 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, News, Serbia

Serbian Prime Minister Aleksandar Vucic speaking at LSE (Photo: Milana Knezevic)

It wasn’t quite a remote controlled drone carrying a provocative political message, but Serbian Prime Minister Aleksandar Vucic’s Monday night lecture at the London School of Economics (LSE) came with its own controversial incident.

“What can you say about the total censorship of all opposition media”, Vucic was asked by a young woman in the audience just as the premier sat down for the question and answer portion of the event. She explained that she was representing Nikola Sandulovic, an opposition politician from the Serbian Republican Party, who was sitting beside her. Sandulovic said later he had travelled to London to confront Vucic.

Chaos ensued. Sandulovic claimed, among other things, that a police officer connected to Vucic had threatened to kill him and that he had evidence contained on a CD he held aloft. Vucic hit back that the Republican Party had only 0.01% of public support, and disputed Sandulovic’s assertion that he had been an adviser to former Serbian Prime Minister Zoran Djindjic, who was assassinated in 2003. Accusations flew across the room until LSE’s moderator James Ker-Lindsay finally managed regain control of the situation.

After the event, Sandulovic told Index he came to London because the media in Serbia ignore him and his party, apart from when government-friendly outlets attack him.

That press freedom was a popular topic on the night did not comes as a surprise. Serbia has seen a string of censorship incidents during Vucic’s time in power, as Index and many others have reported.

The prime minister himself brought up the press in his introductory lecture. He explained how his government has passed several new laws aimed at improving the media landscape, and complained that despite this, they are “scapegoated”. He directly addressed the recent controversial cancellation of a political talk show, Utisak Nedelje (Impressions of the Week), saying authorities have been subjected to a blame campaign for what was a commercial decision. Supporters of the show, including host Olja Beckovic, say it was down to political pressure.

In a joking reference to his infamous role under Slobodan Milosevic, he said he had been the “worst minister of information”. Curiously, he also used this former job as a counterargument to critics, arguing that his past had made it easy to blame him for any instance of censorship.

But this didn’t seem to stop the press-related questions, though none of the journalists present were chosen to ask one. Apart from the memorable Sandulovic intervention, an audience-member pointed out that Utisak Nedelje wasn’t the only show to have been taken off air in recent times.

If there was an overarching theme to the night, it was that it seemed to showcase different — some would say conflicting — sides of Vucic and his administration. He reminded the audience that Belgrade had recently organised a successful Pride parade, before adding that he didn’t want to attend. To have that choice, he argued, was a real mark of freedom.

There were, of course, questions about the football drone. While Vucic said he didn’t want to share his own views, he said UEFA (European football’s governing body) saw Serbia’s side of the story by awarding them the win, before pointing out that Serbia carries its share of the responsibility. The planned state visit from Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama — the first in 68 years — will go ahead, he also confirmed, despite the post-drone postponement.

In response to questions about relations with Russia — just weeks after the Belgrade military parade where Vladimir Putin was the guest of honour — he said the two countries would continue to build their relationship, but that this would have no impact on Serbia’s ultimate goal of European Union accession.

Much has been made of Vucic’s apparent journey from Milosevic man to EU enthusiast. He seemed to reference this as he said he is “not perfect” and that he works “every single day” to change and better himself. But on Monday, he left more questions than answers about the direction he is taking Serbia in.

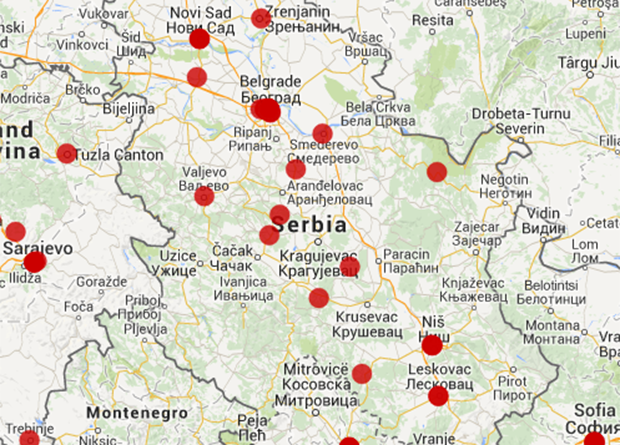

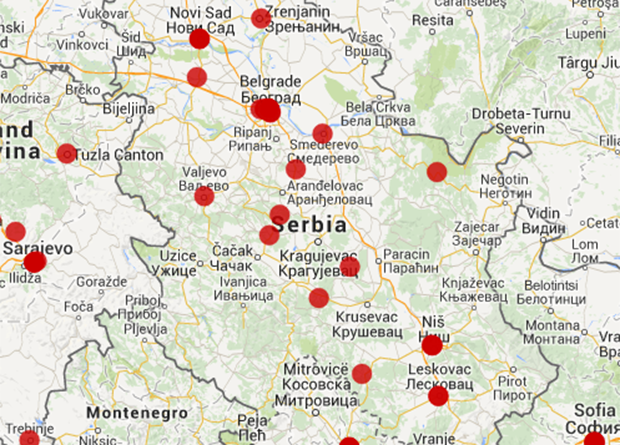

Mapping Media Violations in Europe: Serbia

Five media outlets targeted with DDoS attacks

Protesters criticise cancellation of political talk shows

Deputy mayor fined for insulting journalist

Macedonian journalist released from extradition detention

Photographer injured by anti-pride parade protesters

This article was originally posted on 29 October at indexoncensorship.org

8 Oct 2014 | Mapping Media Freedom, News, Politics and Society, Romania

In November, Romanians are set to head to the polls to elect a new president from a field of 14 candidates during two rounds of polling. But one important participant, the National Audiovisual Council of Romania (CNA), will be sidelined as it loses its legally mandated quorum.

According to the CNA’s website, its role is to “ensure that Romania’s TV and radio stations operate in an environment of free speech, responsibility and competitiveness.”

While the first round of voting is set to get underway on 2 November, the CNA’s quorum of eight will be halved on 4 November when four members of the council step down at the end of their terms. If no candidate wins a majority in the first poll, the top candidates will compete in a second round on 16 Nov.

“Without a quorum, the CNA cannot function, and thus it cannot sanction the eventual abuses of television or radio stations during the election campaign,” said Narcisa Iorga, a CNA board member. Iorga believes politicians will benefit from this, as it is in their best interests to have an inactive CNA. Television stations will also use the situation in their favor, though they are already accustomed to breaking the audiovisual legislation, she added.

According to some members of the council, it could be January before the CNA regains its quorum and the ability to make decisions on issuing sanctions, well after the election campaign and the two rounds of voting.

The CNA is Romania’s only regulatory body overseeing television and radio programmes. In its watchdog role, the regulator ensures that legislation governing programming is respected. It’s a key role in a country where television is the dominant media among the population. Political parties and interest groups use the country’s live television shows to get their message across to the public.

By law, the CNA is supposed to have 11 board members. To maintain a quorum, eight members need to be present at the proceedings. The members, who have a mandate of six years, are nominated by the senate (three members), the chamber of deputies (three), the president (two), the government (three), and are confirmed by the parliament.

This is where politics comes into play: the parliament, controlled by a coalition led by the party of Victor Ponta, the prime minister who is the best-placed candidate at the presidential elections, did not vote to confirm the new members before the parliamentary vacation began. Therefore in less than a month, the CNA will have only seven members, one member short of the quorum.

Not having enough members to be able to take decisions is nothing new for the regulatory body. When there are politically sensitive issues on the table, some of its members usually go on a vacation.

For example, on 9 October a number of complaints against the Antena 3 news television will be debated, but it is more than likely that will be no quorum. Two CNA members are currently on vacation, and another two just announced their absence, wrote Iorga on her Facebook wall.

Media violation reports from mediafreedom.ushahidi.com

Penal code change could ensnare journalists

Falun Gong practitioner detained during interview

Journalists denied access to government building

Director of public television receives “warnings”

Jurnalul National editor assaulted and threatened

This article was published on 8 Oct 2014 at indexoncensorship.org