15 Sep 2014 | Germany, Mapping Media Freedom, News, Politics and Society

Vandals attacked the Lausitzer Rundschaufor the second time in a week.

On the night of September 4-5, the daily newspaper Lausitzer Rundschau became victim to a crime by now familiar to its employees: neo-nazis vandalised the outside of one of its office buildings in the eastern German city of Spremberg, covering it with anti-Semitic graffiti. Less than a week later, on the night of September 8-9, another Lausitzer Rundschau office in the nearby city of Lübbenau faced a similar attack.

The incidents were covered by national and local media in Brandenburg, the state surrounding Berlin. Right-wing extremism has been a sensitive topic for the Lausitzer Rundschau—only two years ago, the newspaper’s Spremberg office was also vandalized by neo-Nazis who left graffiti and an animal carcass outside the building. Shortly before the 2012 attack, the newspaper had reported critically about a right-wing extremist march in Spremberg.

Klaus Minhardt, president of the German Journalists’ Association’s local Berlin-Brandenburg chapter, sees offences like the ones against Lausitzer Rundschau as motivated by a small group of individuals lashing out against specific media reports.

“People like to make journalists their victims and to take revenge out on them. Usually, somebody does something bad and the journalist who uncovers that becomes the face of the issue,” Minhardt said.

A few days before the September 4 attack, Lausitzer Rundschau ran a report on a trial in the nearby city of Cottbus, where police testified that right-wing extremist paraphernalia was found on an alleged assailant’s body. Johannes M. Fischer, editor in chief of Lausitzer Rundschau, says the newspaper’s reporting on the trial is one reason for the recent vandalism. Another, says Fischer, is the upcoming Brandenburg state elections on September 14. Election posters in the area surrounding Lausitzer Rundschau’s offices were also covered in anti-Semitic graffiti after both of the new incidents.

This past week’s attacks on the newspaper were shocking because they were repeated in quick succession. According to Fischer, the kind of vandalisation was also more brutal than the previous incident in 2012.

“The quality is different. It has a horrible quality. The sayings are more violent. ‘Jews, Jews out, gas Jews,’ which was abbreviated as VE.G.,” Fischer said.

Because of the proximity between the two offices in Lübbenau and Spremberg, police have said that the same people are likely responsible for both of the September attacks on Lausitzer Rundschau. Fischer is also convinced that a only a few dozen people are behind the vandalisation, and he stresses that the Lausitz region is tolerant, while locals have expressed support for the newspaper after the attacks.

Lausitzer Rundschau has become well known for its aggressive reporting on neo-nazi activity in the region, which covers parts of the eastern German states of Brandenburg and Saxony. In 2013, two of the newspaper’s reporters won national prizes for their work on right-wing extremists in the area.

The “tough staff,” Fischer says, is not intimidated by the attacks on their offices and is determined to continue covering neo-nazi groups there. Fischer still refers to the vandalisation as a threat, and says he has offered reporters various options if they feel uncomfortable working after the attacks.

“They could switch to a different beat. And we also said, ‘You don’t have to write about this topic,’” Fischer said.

None of the Lausitzer Rundschau journalists took Fischer up on that offer. He adds, “They say, ‘Now we really have to do this.’”

More reports from Germany via mediafreedom.ushahidi.com:

Deutsche Welle accused of censorship

Public broadcaster fires blogger

Photographer arrested at protest

ECHR rules court decision to stop publication about Chancellor Schröder was illegal

Head of state chancellery intimidates journalists with legal warning

This article was published on Monday Sept 15, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

10 Sep 2014 | Leveson Inquiry, News, United Kingdom

“The greatest threat to freedom of the press in our country is our libel law. Why do we have this weird defamation law, where the idea is that if we get something wrong about someone, we have to pay a pile of money? We should correct it with equal prominence. Take money and costs out of the picture. Because, on the whole, only the rich can afford it,” investigative journalist Nick Davies told an audience at the Frontline Club last night.

Davies, who unveiled the extent of the phone-hacking scandal and has just published his book Hack Attack, was in conversation with author and former ITN chief Stewart Purvis (above), talking about hacking, press regulation and this week’s launch of the Independent Press Standards Organisation (Ipso).

Below are some highlights.

On his hacking investigation:

“The crimes weren’t serious enough to spend seven years of your life working on it. What makes it interesting is it’s about power. The thing that Murdoch generates – aside from money and circulation figures – is fear. Once a media mogul has established this kind of fear – he doesn’t have to tell the government, the police or the PCC what to do. They will all try and placate him. That’s really what this book is about and if there is any justification for doing this much work on one story, it’s that.”

On Ipso – which he describes as a “phoney regulator”:

“If Ipso turns out to be subject to the same influences of the big news organisations as its predecessor the PCC, then it is very worrying because Ipso has considerably more power. It has the power to investigate; it has the power to levy fines. You imagine what would have happened if that had been in place when we were investigating phone hacking. They could have killed that story off.”

On the greatest threat to freedom of the press:

“The greatest threat to freedom of the press in our country is our libel law. Why do we have this weird defamation law, where the idea is that if we get something wrong about someone, we have to pay a pile of money? We should correct it with equal prominence. Take money and costs out of the picture. Because, on the whole, only the rich can afford it.”

On whether the truth has caught up with Murdoch, as the book’s subheading suggests:

“There was a moment when the truth caught up with Murdoch – that day in Parliament with his son – but slowly the power comes back. Now he is meeting Nigel Farage [Ukip leader] as if this Australian with American citizenship has any sort of influence at all about what happens in our next election. What is wrong with our system that he is allowed to display such arrogance? We are the voters. It will be interesting to see if in the run up to the 2015 elections he and his newspapers throw their weight around as usual. I fear we will see a familiar pattern, as the bully in the playground.”

On the future of journalism:

“The biggest best hope for journalism is that it continues to attract energetic, bright, idealistic young people. But then you see them being fed into this mincing machine. The key to our revival is fixing the broken business model. We need to find a solution to this problem.”

On the internet:

“[With internet news], you end up with fragmentation. The communist produces news for communists, the racist produces news for racists. Nobody is factchecking, nobody is accountable. It’s much worse, potentially, than the mainstream news organisations that come in for such a kicking. The internet is potentially a very destructive force. I’m not necessarily saying it will go this way, but it could rank up there with nuclear weapons, where you say, ‘Christ, that was clever of us to invent that, but we potentially wish we hadn’t done it’. I just don’t know where it is going to go.”

On citizen journalism:

“In an ideal world, we should have professional journalists. There are too many people on the left whose knee-jerk reaction is to assume that all journalists working for big corporations are corrupt and unable to tell the truth. To dismiss journalists from these organisations going to Syria and Iraq and risking their lives as corporate puppets is really disgusting. There is a belief that if the profession of journalism dies out, we’ll be better off with citizen journalists. Do you want citizen doctors too?”

On who he’d like to play him in the film version of his book (the rights to Hack Attack having just been bought by George Clooney):

Colin Firth

Join us to debate the future of journalism and whether it might lead to democratic deficit at the Frontline Club on October 22, or subscribe to Index on Censorship magazine to read our special report on the future of journalism and whether the public will end up with more knowledge or less.

This article was posted on 10 Sept 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

27 Aug 2014 | Asia and Pacific, India, News

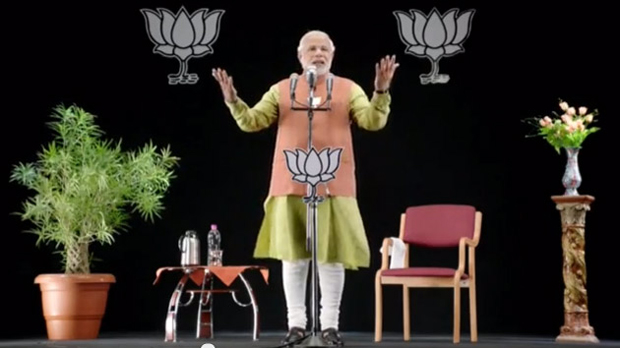

While campaigning to become prime minister, Narendra Modi addressed voters through 3D technology on several occasions (Photo: Narendramodiofficial/Flickr/Creative Commons)

Indians don’t usually take much notice of the prime minister’ speech on independence day in the middle of August. This year was different. This year there was so much discussion on social media that it became a trending topic.

In contrast to the way other prime ministers have handled this moment, new Prime Minister Narendra Modi of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), wowed a large section of Indian society not just with what he said, but the way he said it. People are gushing over the fact that he spoke without notes, and did not use the usual bulletproof glass. Others are impressed with the content; he touched upon topics as diverse as rape, sanitation, manufacturing, and nation building, using easily accessible language. Modi is also using social media to get his views across direct to the public, and bypassing the mainstream media.

This straight-talking style only adds to Modi’s brand, but he is also attracting criticism from the mainstream media for not being willing to answer hard questions. His chosen methods of communicating with the public have one common thread: he prefers to address the public directly, plainly, without going through the mainstream media or any reliance on further explanation by them. His social media accounts on Facebook and Twitter have completely changed the way information comes out of the prime minister’s office (PMO). Modi’s tweets, both from his personal and his prime ministerial account, keep citizens updated on his various trips (“PM will travel to Jharkhand tomorrow. Here are the details of his visit”). He also updates on his musings (“I am deeply saddened to know about Yogacharya BKS Iyengar’s demise & offer my condolences to his followers all over the world”) and highlights from speeches made across the country (“when the road network increases the avenues of development increase too”), as well as photographs and videos. Citizens are getting a front row seat at his speeches and thoughts. But not everybody is happy about this — especially not the private mainstream media.

Unlike the previous government, Modi is yet to appoint a press advisor. That person, normally chosen from senior journalists in New Delhi, advises the prime minister on media policy. There isn’t a point person from the PMO for the mainstream media — or the MSM, as it is called — to discuss stories and scoops. He only takes journalists from the public broadcasting arms — radio and TV — on his foreign trips, in contrast to his predecessor, who brought along more than 30 journalists from the public and private channels. In fact, Modi has reportedly instructed his MPs to refrain from speaking to journalists. Indian mainstream media is filled with complaints that Modi is denying journalists the opportunity to engage with complex subjects like governance beyond official statements and limited briefings. Meanwhile, some other publications have scoffed that the mainstream media is only complaining because it will be forced to analyse the news and work towards coherent reporting instead of relying of well honed cosy relationships with people in power.

This apparent rift between the PMO and the private mainstream media has to be viewed through a variety of prisms for it to make any sense. The first is the very volatile relationship between Modi and the MSM which harks back to his time as chief minister of Gujarat, when a brutal communal riot took place. The second is the state of the mainstream media itself, continuously called out for unethical practices by the likes of the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India.

The relationship between Modi and the mainstream media is complex. No court has indicted Modi for any criminal culpability in the Gujarat riots of 2002, but many in the media have held him morally responsibly for the mass killings that carried on over three days, and let their feelings colour reports on him. But right before Modi’s historic sweep of the Indian general elections, this section of the press seemed to have begrudgingly warmed to the man they had long vilified.

One of India’s most respected journals, Economic and Political Weekly, published the article Mainstreaming Modi, deconstructing this new wave of coverage. It argued that the reasons for this change “range from how even the United Kingdom and the European Union have ‘normalised’ relations with him [Modi], that he has been elected thrice in a row to the chief ministership of Gujarat, which surely speaks of his abilities as an ‘efficient’ and ‘able’ administrator, that Gujarat has become corporate India’s favourite investment destination, and most importantly, that he is the guy who can take ‘decisions’ and not keep the nation waiting for action.”

During this year’s election campaign, Modi’s use of the media was innovative. Stump speeches were tailor made for the towns he was campaigning in. Modi’s 3D holograms, deployed in small towns while gave a speech elsewhere, were a spectacle not seen before in India. Though Modi had been speaking to Hindi and other Indian language media, he delayed giving interviews to the English language “elite” media, watched by a small but influential section of the population. He finally consented to doing a one-on-one interview with Arnab Goswami of Times Now, known as one of India’s loudest and most aggressive anchors. People readied themselves for the ultimate combative hour on television, but Modi’s no-nonsense answers, it seemed, won over both the anchor and the audience — especially as they were in sharp contrast to the vague statements put across by Modi’s challenger, Indian National Congress Party candidate Rahul Gandhi.

After the election win, India’s mainstream media has been forced to reassess what it wants from the prime minister. Is it information or is it access? The mainstream media undoubtedly has had a very complicated and close history with the political class. A Congress-led government has been ruling New Delhi for a decade, building up close relationships with senior editors and journalists. Some of these relationships were exposed through leaked conversations between members of the press and corporate lobbyists in a scandal now known as the Radia Tapes. They revealed, among other things, how journalists used their connections to politicians to pass on messages from lobbyists.

In fact, the indictment of improper behaviour by the media is a fairly regular occurrence in India. Just this month, the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India released their latest report, which recommends that corporate and political influence over the media can be limited by restricting their direct ownership in the sector. For this reason, the credibility and true affiliation of the media is always under the scanner.

But Modi and his team also need to respond to questions about why they will not deal with some parts of the media. How do they view the role of a combative media? Is only the public broadcaster, which reports the story as the government wants, to be allowed access? Are critical questions being avoided?

Perhaps, the last word can go to Scroll.in, one of India’s newest online magazines: “[T]he rat race for the ego scoop undermines the most important scoop, the thought scoop. We often don’t look at the big picture, don’t take the long view, don’t see the obvious, forget the past, don’t study the boring reports, substitute access journalism for ground reporting, believe the official word. Narendra Modi might just be doing us a favour by keeping us away.”

This article was posted on August 27, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

21 Aug 2014 | Americas, News, United States

A number of journalists have been arrested while covering the protests in Ferguson, Missouri (Photo: Abe Van Dyke/Demotix)

As news spread of a video showing the murder of American journalist James Foley by the Islamic State (ISIS), journalists and Middle East watchers were unanimous on social media: do not watch the film. And for God’s sake do not post links to the film anywhere. Do not give the killers what they want.

The descriptions were brutal enough. They echoed back over a decade, to the murder of Daniel Pearl by Al Qaeda linked terrorists in Pakistan 2001.

There is a very specific message in the public execution of journalists. It’s a hallmark of extremism, in that it signifies that your movement is far beyond attempting to use the press to “get the message out”, to garner support. This is not about rational grievances the international community could address. This is not about convincing anyone who isn’t already open to your ideas. It’s about rejecting traditional ideas under which the press operates.

But this is partly possible because the likes of ISIS no longer need the attention of press to reach the world. Much has been made of the group’s social media presence. It’s genuinely impressive, and, importantly, clearly the work of people who have grown up with the web; people who are used to videos, Instagram, sharable content. They are, to use that dreaded phrase, “digital natives”. They understand the symbolic power of murdering a journalist, but they see themselves as the ones in charge of controlling the message.

Media workers are increasingly targeted, while the previous privileges they enjoyed fade away.

As I sat down to write this column, the number of journalists arrested while covering disturbances in Ferguson, Missouri stands at 17. According to the Freedom of the Press Foundation, this number includes reporters working for German and UK outfits, as well as domestic American media.

Journalists have apparently been threatened with mace. An Al Jazeera crew had guns pointed at them and their equipment dismantled. A correspondent for Vice had his press badge ripped off him by a policeman who told him it was meaningless (in slightly coarser language).

The Ferguson story is a catalogue of things gone wrong: racism, disenfranchisement, the proliferation of firearms, a militarised police force (a concept that goes far beyond mere weaponry; this is law enforcement as occupying force rather than as part of a balanced democracy). To single out the treatment of media workers may seem a little self serving, but there is good reason to do so.

We are used to telling ourselves by now that journalism is a manifestation of a human right — that of free expression. Smartphones, cheap recording equipment, and free access to social media and blogging platforms have revolutionised journalism; the means of production have fallen into the hands of the many.

This is a good thing. The more information we have on events, surely the better. But one question does arise: if we are all journalists now, what happens to the privileges journalists used to claim?

Official press identification in the UK states that the holder is recognised by police as a “bona fide newsgatherer”. As statements of status go, it seems a paltry thing. But it does imply that some exception must be made for the bearer. The recognised journalist, it is suggested, should be free to roam a scene unmolested. One can ask questions and reasonably expect an answer. One can wield a video or audio device and not have it confiscated. One can talk to whoever one wants, without fear of recrimination.

That, at least, is the theory. But in Britain, the US and elsewhere, the practice has been changing. Whether during periods of unrest or after, police have shown a disregard for the integrity of journalists’ work. The actions of police in Ferguson have merely been part of a pattern.

The question is whether we can maintain the idea of journalistic privilege when everyone is a potential journalist.

During the legal tussles over the case of David Miranda, the partner of former Guardian writer Glenn Greenwald, an attempt was made to identify persons engaged in journalistic activity, without necessarily being employed as journalists.

Miranda was detained and searched at Heathrow airport as he was believed to have been carrying files related to Edward Snowden’s NSA leaks, with a view to publication in the Guardian, though he is not actually a journalist himself.

The suggestion made by Miranda’s supporters (Index on Censorship included) is that the activity of journalism is what is recognised, rather than the journalist.

This may be applicable in circumstances such as a border search, but how would it apply in the heat of the moment in somewhere like Ferguson, or during the London riots, or any of the recent upheavals where citizen footage has proliferated. If someone starts recording a confrontation with the authorities, are they immediately engaged in journalistic activity? Or does journalism depend on what happens to your video, your pictures, your tweets?

When everyone is a journalist, is anyone?

This article was posted on August 21, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org