22 Jan 2014 | News, Pakistan, Politics and Society

Pakistan’s Express News has been target of attacks by the TTP, including one which claimed the lives of three media workers.

Condemning the cold blooded assassination of three media workers belonging to a private television channel, the Pakistani media has united against the culture of impunity that has gripped the country.

The audacious attack happened on 17 January in Karachi, when a group of men on motorbikes, fired a volley at close range inside Express News’ van stationed in North Nazimabad. The sole survivor was a cameraman. Soon after, the Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) contacted the television station and claimed responsibility for the attack.

TTP spokesperson, Ehsanullah Ehsan, said: “To kill certain people is not our aim”. The group said it targeted the media workers because they were “part of the propaganda against us”.

Analyst and director of media development at Civic Action Resources, Adnan Rehmat, believed the attack was “meant to browbeat and cow down a media that is becoming more outspoken and starting to criticize the Taliban”.

“It’s clearly a message to the whole of Pakistan’s independent media — to intimidate it and make it toe the militants’ line,” agreed Omar R. Quraishi, editor of the editorial pages of the English language Express Tribune, which is Express News’ sister organisation.

“What needs to be understood by all journalists and media groups in Pakistan is that an attack on Express Media Group is an attack on the whole media,” he pointed out.

“Express maybe in the firing line at the moment, but this is nothing short of an attempt to intimidate the media itself, and it will work,” journalist Zarrar Khuhro, of English daily, Dawn newspaper, formerly of ET, also conceded.

“This is because the state itself is so supine in the face of terrorists,” he said and added: “How can we expect one media group, or journalists as a whole, to take a stand when those who are supposed to protect the citizens of this country are bent upon negotiating with killers?” He was referring to the ruling Pakistan Muslim League’s insistence give peace a chance by holding dialogue with the Taliban.

Khuhro was, however, not entirely sure why ET was being singled out by the Taliban. ” Previously there have been rather insane social media campaigns against Express and it has been accused by the lunatic fringe of running anti-Pakistan and anti-Islam campaigns,” he told Index.

Ehsan said the Express TV had been attacked because the Taliban group considered its coverage “biased” and that it would continue to attack journalists they disagreed with. “Channels should give coverage to our ideology; otherwise we will continue attacking the media,” Express TV quoted him as saying.

This was the third such attack on the Express Media Group — which includes the Express Tribune and the Urdu-language daily Roznama Express, in addition to the television channel — in the last six months. In August and then again in December, unidentified gunmen shot at their newspaper office, in Karachi. Taliban claimed responsibility for the December incident.

But what is frustrating is that not one perpetrator has ever been caught. “This is a spectacular failure of the state and of the media sector’s ability to defend itself,” said Rehmat.

“If those involved in previous attacks had been caught, perhaps they would not have been emboldened to continue this campaign against the media,” said media analyst Owais Aslam Ali, secretary general of the Pakistan Press Foundation.

Rehmat finds a “fairly consistent pattern” in “these string of attacks” with over 100 journalists and media workers killed since 2000.

The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) found soaring impunity rates in Somalia, Pakistan, and Brazil in 2013. The CPJ publishes an annual Impunity Index, which calculates unsolved journalist murders as a percentage of each country’s population. “Pakistan’s failure to prosecute a single suspect in the 23 journalist murders over the past decade has pushed it up two spots on the index. A new onslaught of violence came in 2012, with five murders,” stated the report.

But these attacks have put the Pakistani media in an ethical conundrum: How much airtime to give to the Taliban to keep them appeased?

“Media is now confronted by a double whammy challenge — wail about terrorism while simultaneously giving air time to those who perpetrate this violence,” said Fahd Hussain, news director at Express News.

“There is no easy answer and no formulaic editorial decision making process. What makes it even harder for the media to take a clear stance is the deep fissure within the media industry itself,” he told Index.

But experts say while training of journalists towards safety can help mitigate the problem to some extent, the government must act proactively as well.

“What is needed is for the government to appoint a special full-time prosecutor dedicated to investigating attacks against the media and for the media houses to adopt and implement best practices in safety protocols,” said Rehmat.

This article was published on 22 January 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

2 Jan 2014 | Egypt, News, Politics and Society

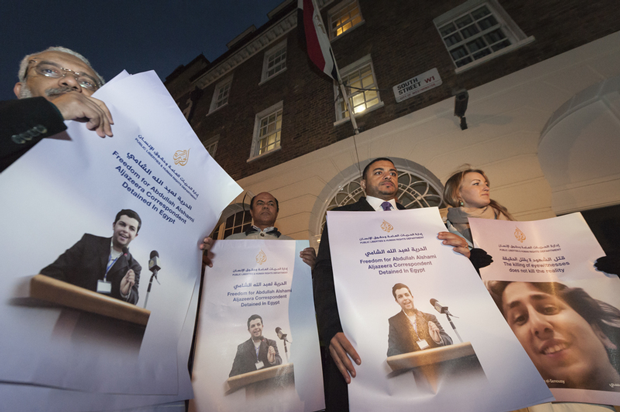

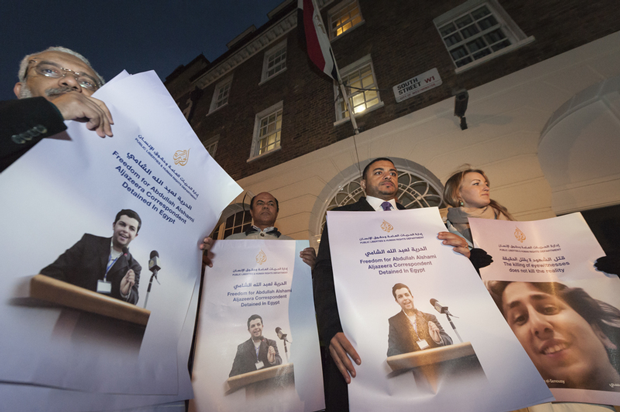

In November 2013, the National Union of Journalists (NUJ UK and Ireland), the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) and the Aljazeera Media Network organised a show of solidarity for the journalists who have been detained, injured or killed in Egypt. (Photo: Lee Thomas / Demotix)

In a new sign of a regression in press freedom in Egypt, authorities have ordered three journalists working for the Al Jazeera English (AJE) channel held in custody for fifteen days.

The journalists –AJE Cairo Bureau Chief Mohamed Fadel Fahmy, award-winning former BBC Correspondent Peter Greste and producer Baher Mohamed–were arrested in a police raid on Sunday on a makeshift studio at a luxury Cairo hotel. They were charged with “belonging to a terrorist group and broadcasting false news that harms national security .”

Cameras and other broadcasting equipment were seized during the raid on the work room where the AJE TV crew had reportedly conducted interviews with activists and Muslim Brotherhood members on the political crisis in Egypt. A fourth member of the AJE team–Cameraman Mohamed Fawzy–was also arrested but was released hours later without charge.

The latest detentions raise the number of journalists affiliated with Al Jazeera and who are now jailed in Cairo , to five. Al Jazeera Arabic correspondent Abdullah Al Shami was arrested on 14 August while covering the brutal security crackdown on supporters of toppled President Mohamed Morsi at Rab’aa–the larger of two encampments where pro-Morsi protesters had been demonstrating against his forced removal and demanding his reinstatement. Al Jazeera Mubasher Misr Cameraman Mohamed Badr was meanwhile, arrested on 15 July while covering clashes between security forces and pro-Morsi protesters in Ramses Square.

Al Jazeera has denounced the arrests of its staff members as an act designed to “stifle and repress the freedom of reporting by the network’s journalists.” The Egyptian government’s hostility towards journalists affiliated with the Qatari-based network has been prompted by what many Egyptians perceive as “a pro-Muslim Brotherhood bias in the network’s coverage of the events unfolding in Egypt”. Since the military takeover of the country in July 2013, at least 22 staff members have resigned from AJ Jazeera Mubasher Misr, the Egyptian arm of the network , over the alleged “bias in favour of the Islamist group”. Al Jazeera has however, denied the allegation.

The latest detentions are perceived by analysts as part of the crackdown on the Muslim Brotherhood–the Islamist group from which the deposed President hails. Last week, the group was officially classified as a “terrorist organization” by the Egyptian authorities, in a move criminalizing the group’s activities, financing and membership .

The arrests of the AJE journalists have also raised fears among rights activists and organizations that the government crackdown was “widening to silence all voices of dissent”. Human Rights Lawyer Ragia Omran told the New York Times on Monday the charges are “part of a pattern of aggressive prosecutions–including conviction of protesters— that were rarely pursued even under Hosni Mubarak.” The New York-based Committee For the Protection of Journalists , CPJ, has also condemned the arrests, calling on the Egyptian government to release the journalists immediately . In a statement released by CPJ, Sherif Mansour, Middle East and North Africa coordinator , said ” the Egyptian government was equating legitimate journalistic work with acts of terrorism in an effort to censor critical news coverage.” In its annual census conducted last month, the CPJ ranked Egypt among the top ten jailers of journalists in the world with at least five journalists languishing in Egyptian prisons. It has also listed Egypt among the three most dangerous countries for journalists in the Middle East after Syria and Iraq . Six journalists have been killed in the country over the course of the past year, three of them while covering the bloody crackdown on Morsi’s supporters at Rab’aa.

Members of Mohamed Fahmy’s family meanwhile used his Twitter account to send a message on Tuesday reminding the government that “journalists are not terrorists.” His supporters meanwhile started a hashtag on Twitter calling for his release. Many of them expressed disappointment at what they described as “the government’s latest act of repression” warning that it would harm the government’s image much more than any amount of critical reporting would.

This article was posted on 2 Jan 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

9 Dec 2013 | Volume 42.04 Winter 2013

The upcoming winter issue of Index on Censorship magazine includes a special report on religion and tolerance, with articles from around the world.

The upcoming winter issue of Index on Censorship magazine includes a special report on religion and tolerance, with articles from around the world.

Writers include the Bishop of Bradford, Salil Tripathi, Samira Ahmed and Kaya Genc. There’s an interview with Gurpreet Kaur Bhatti ahead of the opening of her new play, and 10 years after Behzti; while cartoonist Martin Rowson writes and draws about how comedy and religious offence come into conflict. Natasha Joseph writes from South Africa on why some portraits of President Zuma made him see red. Alexander Verkhovsky discusses the new blasphemy law in Russia, and former BBC mobile editor Jason DaPonte discusses why computer games are not all bad.

As part of the special report, writer Brian Pellot goes online with the Mormons to see how they use technology to talk to the unconverted, and asks if online chats will replace missions. Germans have been outraged by the revelations about US and UK surveillance, now they have plans to do something different to put a stop to snooping in the future, Sally Gimson reports. From Brazil, Ronaldo Pelli looks at the reaction to people practising religions of African origin, and investigative writer and author of Fast Food Nation Eric Schlosser talks about the threats to investigative journalism now and in the future.

Also in this issue:

Padraig Reidy on flags, controversy and Northern Ireland

Xiao Shu on the Chinese crackdown on the New Citizens’ Movement

Kaya Genc on the rise of a new type of media in Turkey

3 Dec 2013 | Egypt, News, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture

Egyptians gathered on the in Corniche near Qasr Nil Bridge in July 2013 to celebrate news of the announcement by the Egyptian Army Chief General el Sisi, that President Morsi had been removed from power in “response to the will of the people.” (Photo: Sharron Ward / Demotix)

Last week, when Egyptian security forces violently dispersed activists rallying against a controversial new anti-protest law, Egyptian media was full of praise for them the following day. Instead of condemning the excessive use force by riot police who beat, sexually assaulted and detained scores of opposition protesters, newspaper editors portrayed the Interior Ministry as “the victor” in the confrontation over the new gag law.

“The Interior Ministry has passed the test on the anti-protest law,” read Wednesday’s bold red headline in the semi-official Al Ahram daily. The independent Al Watan, meanwhile, declared on its front page that the Ministry of Interior had “decidedly resolved the battle over the anti-protest law.”

Headlines, editorials and articles labelling democracy activists “anarchists and “thugs” signal that most Egyptian media has reverted to its old pre-revolution ways, siding with the military-backed government against the opposition. During the January 2011 mass uprising that toppled former President Hosni Mubarak, Egyptian media had vilified the opposition activists, describing them as “foreign agents” and “hired thugs.”

Media discourse in Egypt today is reminiscent of the Mubarak era. Then, almost all media outlets had adopted the state line and carefully avoided crossing the so-called ‘red lines’. The only difference is that today, the media has voluntarily and ungrudgingly aligned itself with the military-backed government. During Mubarak’s tenure journalists were motivated by fear of falling out of favour with the authoritarian regime. Ironically, since Muslim Brotherhood President Mohamed Morsi was toppled by military-backed protests last July, the Egyptian media’s support for the country’s powerful military has come with little coercion from the generals who are riding a wave of popularity and ultra-nationalist sentiment.

Since Morsi’s ouster, the Egyptian media has glorified the military while persistently demonising both the Muslim Brotherhood and the deposed Islamist President, continuing the vilification trend it had started when the former president was still in power. Morsi’s supporters have consistently been branded “terrorists” and “liars” by Egypt’s state-owned and private media alike. As Morsi’s supporters staged a sit in last July demanding “the reinstatement of the legitimate president”, Youssef El Husayni, a presenter on the privately-owned channel ON TV accused the protesters of murder, saying that they “deserved to be hanged.” Other TV talk show hosts also accused the anti-coup protesters of “getting paid to stay on the streets”. On November 4, the day Morsi’s trial began, the former president was labelled “hysterical” by several Egyptian newspapers including the independent El Youm el Sabe’e and El Masry El Youm for insisting he was still the country’s legitimate president and could not be tried by the court. He was also criticized by journalists for refusing to wear his prison uniform to court–a decision that drew unfavourable comparisons with his predecessor Hosni Mubarak who had previously appeared in court in the white garment.

Earlier this month, the privately-owned network CBC suspended satirist Bassem Youssef’s wildly popular show Al Bernameg (The Programme) after an episode that poked fun at the public fervour for the military and in particular, at the ‘Sissi-mania’ gripping the country. Egypt’s De facto ruler El Sissi earned the adoration of millions of Egyptians when he ousted Morsi, positioning himself as the “guardian of the people’s will” and claiming he had “saved the country from a looming civil war.” He has since been compared by some Egyptian media to Egypt’s former ultra-nationalist leader Gamal Abdel Nasser. In recent months, there have increasingly, been calls for El Sissi to run in the next presidential election.

Surprisingly, the decision to take Youssef’s show off the air came from CBC’s senior management not–as many had initially believed–from strongman El Sissi. Youssef’s last episode met with a public outcry and almost immediately after the broadcast, CBC issued a statement distancing itself from the comedian’s views. The station blamed the suspension of the show on “technical” and “business” issues rather than on the show’s editorial content. CBC’s decision has led to fierce public criticism of the network which had previously given Youssef a free hand to mock former President Mohamed Morsi and his Islamist group. Throughout Morsi’s one year term in office, Youssef had relentlessly kept up his attacks on the former President despite repeated threats of legal action against him. Many of Youssef’s fans have threatened to boycott CBC after the TV satirist quit the channel over the suspension of the show.

Meanwhile, the “red lines” are back at Egyptian State TV where show presenters and anchors have kept up the pro-military rhetoric in recent months for fear of being stigmatized as “pro-Muslim Brotherhood ” and “fifth columnists.” The latter is a term that is being widely used to describe sympathizers or supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood whose activities were banned by a court ruling in November. Presenters who are suspected of being sympathetic to the outlawed Islamist group are being deprived of air time. Several presenters have faced investigations in recent weeks over “their shameful links to the enemy Islamist group”. Journalists have been repeatedly accused of “destroying the country and wreaking havoc to abort the goals of the revolution.” A list of names of so-called “fifth column TV presenters and activists” has gone viral on social media networks Facebook and Twitter after being posted on several local websites with the declared aim of “exposing and sidelining the traitors.” Those on the list–which includes reform leader El Baradei, revolutionary activists and prominent TV journalists known for their objectivity–have also being accused of receiving foreign funding.

Many journalists have again resorted to practising self-censorship for fear of being labelled “enemies of the state.” Ironically, the pressure on them has come from fellow-journalists rather than from the generals themselves. Those piling the pressure are journalists who were either appointed by the ousted Mubarak regime or others with strong links with the country’s notorious security services. In September, controversial talk show host Tewfik Okasha, who is also the owner of the private El Fara’een Satellite Channel, gave Defence Minister El Sissi “an ultimatum to purge the media of fifth columnists”. Abdel Rahim Ali, the chief editor of El Bawaba news site, meanwhile told Al Midan TV in September that “those who oppose the reinstatement of state security are from the fifth column.” He did not hesitate in naming the activists and political figures he suspected had links with the “Islamist terror organization.” Responding to a list of suspect-fifth columnists published in the state-owned Al Ahram El Arabi in September, veteran columnist Fahmi Howeidi warned that “such accusations only serve to further empower the country’s notorious state security service, the SSS.” The SSS, known in Egypt as “Amn El Dawla” was a symbol of police oppression under ousted President Hosni Mubarak. It was disbanded in March 2011 only to return a month later, albeit under a different name–the National Security Service.

The “Fifth Column Campaign” targeting government critics with the aim of silencing voices of dissent, has succeeded in fulfilling its objective, lament rights campaigners.

“In this atmosphere of deep political divisions and at a time when anyone can be accused of espionage for merely mentioning such ‘taboo’ words as ‘coup’ and ‘reconciliation’, many in our profession have opted to play it safe by siding with the stronger power–the military. This is an indirect way of muzzling the press and unfortunately, it is working,” Sameh Kassem, Cultural Editor who works for the independent Al Dostour said.

In the ‘new Egypt’ –now once again under the tight grip of military rule — where scores of journalists have been assaulted and detained for covering the anti-coup protests, the critics are falling silent.

This article was published on 3 Dec 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

The upcoming winter issue of Index on Censorship magazine includes a special report on religion and tolerance, with articles from around the world.

The upcoming winter issue of Index on Censorship magazine includes a special report on religion and tolerance, with articles from around the world.