Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]This article is part of Index on Censorship partner Global Journalist’s Project Exile series, which has published interviews with exiled journalists from around the world.[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text] The calls came to Tajik journalist Humayra Bakhtiyar at her sports club, at the shopping center and at home. Whatever she was doing, agents from Tajikistan’s State Committee for National Security wanted her to know that they knew about it.

The calls came to Tajik journalist Humayra Bakhtiyar at her sports club, at the shopping center and at home. Whatever she was doing, agents from Tajikistan’s State Committee for National Security wanted her to know that they knew about it.

Then there were the social media attacks by pro-government trolls: the unflattering photoshopped images of Bakhtiyar and innuendo about her family on Facebook. There were reports attacking her in government media. Finally, there was the official from the former Soviet republic’s security service, still known colloquially as the KGB, who came to the office asking about her family members and why she was putting herself in such a dangerous situation. Would she consider spying on her colleagues for him?

At issue was Bakhtiyar’s reporting on corruption, human rights and other sensitive issues in the central Asian nation for news outlets including the Russian-language Asia-Plus news site, the Institute for War and Peace Reporting and Turkey’s Anadolu Agency.

Such reports were particularly sensitive during presidential elections in 2013 and parliamentary elections in 2015, both won by the ruling party of Tajik President Emomali Rahmon amid criticism from outside observers. Fearing for her safety and that of her family, Bakhtiyar moved to Germany in 2015.

President Rahmon, whose official titles include “Founder of Peace and National Unity,” has ruled the country of 9 million since 1992 in part by imposing severe restrictions on the media. In 2019 Tajikistan ranked 161st of 180 countries on Reporters Without Borders World Press Freedom Index, which notes that much of the country’s independent media has been eliminated. “Harassment by the intelligence services, intimidation and blackmail are now part of the daily routine” for journalists in the country, according to the Paris-based press freedom group.

The U.S.-backed Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, one of the few independent news organizations to operate in the country, is routinely blocked by the government – despite criticism that an RFE/RL local language affiliate has itself become a voice for government propaganda. But RFE/RL is far from alone in facing censorship. Following the killing of four foreign tourists by Islamic State militants last year, much of Tajikistan’s internet was shut down.

Now living in Hamburg, Germany, Bakhtiyar spoke with Global Journalist’s Kyle LaHucik about her budding career as a Tajik journalist and the threats she faced for reporting criticism of the government. Below, an edited version of their conversation:

Global Journalist: Why did you want to go in to journalism?

Bakhtiyar: I wanted to become a diplomat in my school years. But later, I understood that my family cannot pay for me. I never wanted to become a journalist, but when I started to study, I really loved it. From my third year, I started to work full time. From early morning I’d work, and then in the afternoon I went to university to study. From 2007 to 2009, I worked overnight. Many times I slept in my office.

GJ: What subjects did you report on?

Bakhtiyar: At first, I started with social issues. But in early 2008, I was sent to parliament to report. [At] first, I really hated it because it was so boring to listen to the old men talking. But later I started to [take] interest. What does it mean? Why are they sitting there? Why are they writing what they are writing? For whom?

…After that, I started to be interested much more about the government, about who is in government, about nepotism and human rights.

GJ: Tell us about some of the human rights and government issues that interested you.

Bakhtiyar: People really don’t have any rights. When you are getting married, girls have to have this test or papers that say they reserved their virginity and can marry. Even Tajik emigrants who have to move to Russia for work, they also don’t have any rights in Russia and really no rights in Tajikistan. When you go to the hospital there is not good service, and for some doctors you have [pay bribes] because they have really low salaries.

But from Tajikistan government news you will get information that you are really living in some paradise.

GJ: How did the government try to silence you?

Bakhtiyar: I worked more or less 10 years in Tajikistan. I covered all issues: government, parliamentary corruption, nepotism, and the financial system, which is so horrible.

In early 2013, I got some messages from the KGB, the security police: I have to be careful writing, I have to stop covering some issues. In 2013 we had a presidential election, so that’s why I think the security police started to control all mass media. They started to talk to every editor first. They started to push journalists through the editors. Three or four times they contacted my chief editor at a Tajik newspaper and advised them to stop me.

My chief editor informed me every time that the security police want to talk to me. They have some special topic they want to discuss. Every time I ignored this. I said, “I don’t have anything to share with them.”

Later, they came to my office to talk with me. They asked that I talk to them, and when I talked, they asked me to come to the security office. I didn’t want to go because I was afraid. I heard how some activists and journalists have had some accidents that year. I said that if you have any official reasons to talk to me, you have to send me an official letter [that states] why, who you are, why you want to talk to me.

GJ: What did the internal security agent say in response?

Bakhtiyar: [He asked] “How are you living? How is your family? What is your father doing? Where is your mother? Is she alive? How are your brothers?”

I got the message that he already knew everything about my life. My parents are divorced for 18 years [something] I never shared with my colleagues. I lived with my father and my stepmother.

He asked me: “Do you have good relations with your stepmom?”

I tried to be so calm. I told him: “If you are so interested in my family, one day you should come for dinner and I can introduce you to them if they are so important for your office.”

He started to change our conversation and said, “You are so young, so young and so beautiful. Why are you trying to put yourself in a dangerous situation?…You are doing wrong things, your opinion is wrong, everything that you said is bad in our country is not bad. We should keep our peace. You should support our government, it is [a] really nice government.”

I said, ” I don’t want to hear from you…[I] suggest you’re free to go.”

And he just said, “You can write something as you want, but you can work with us. For example, share about what people are talking [about] around you, especially in your office, your colleagues.”

I was so angry, I asked him, “Are you serious?”

Then he started to call me many times and every time when he calls me he informed me that he knows where I am at that moment: when I was at home, when I was at my office, when I was in the shopping center or even my sports club. He really persecuted me and later I started to feel that some people are following me on the street, but I tried to ignore it.

GJ: Did this continue?

Bakhtiyar: Later they started a social attack. There were many, many of my photos published on social media, some Russian social media but mostly Facebook, because I was really active on Facebook. There were many of my photos [that were] Photoshopped and many, many wrong and dirty rumors about my life, about my family. They started to write that I have some psychological problem because I grew up with a stepmother. All the time I knew that they have just one goal: they want to see me out of journalism.

In 2015, we had a parliamentary election. I was really so active, I wrote about it. In some government newspapers they wrote some articles against me. It makes you a bit tired, morally. During this moment, one of my friends in Tajikistan, my colleague and my friend, he [suggested] that maybe I can get some scholarship outside for a short time and maybe it can help me to get a bit of rest. When I will be out of Tajikistan, they cannot see me every day. Maybe they will forget about me. I was really, really tired to live under such pressure.

We found a scholarship at [German news network] Deutsche Welle in Bonn, Germany in May 2015. They said that you are free, you can write about anything. Immediately after my second article, the Deutsche Welle editor got a letter of complaint from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Tajikistan. They invited a Deutsche Welle correspondent in [Tajik capital] Dushanbe in and pushed him to say how I got an internship. What am I doing in Deutsche Welle in Bonn? Who helped me? Why am I writing from Germany about Tajik issues?

My editor just told me: “Don’t be afraid…we will stand behind you. Just continue what you think is right.”

And I continue to write. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/6BIZ7b0m-08″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship partner Global Journalist is a website that features global press freedom and international news stories as well as a weekly radio program that airs on KBIA, mid-Missouri’s NPR affiliate, and partner stations in six other states. The website and radio show are produced jointly by professional staff and student journalists at the University of Missouri’s School of Journalism, the oldest school of journalism in the United States. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Don’t lose your voice. Stay informed.” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship is a nonprofit that campaigns for and defends free expression worldwide. We publish work by censored writers and artists, promote debate, and monitor threats to free speech. We believe that everyone should be free to express themselves without fear of harm or persecution – no matter what their views.

Join our mailing list (or follow us on Twitter or Facebook). We’ll send you our weekly newsletter, our monthly events update and periodic updates about our activities defending free speech. We won’t share, sell or transfer your personal information to anyone outside Index.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][gravityform id=”20″ title=”false” description=”false” ajax=”false”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content”][vc_column][three_column_post title=”Global Journalist / Project Exile” full_width_heading=”true” category_id=”22142″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]This article is part of Index on Censorship partner Global Journalist’s Project Exile series, which has published interviews with exiled journalists from around the world.[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text] When Turkish journalist Arzu Yildiz reported a major scoop in 2014, she had little idea that the story might lead to the end of her journalism career, the loss of her home, and separation from her family.

When Turkish journalist Arzu Yildiz reported a major scoop in 2014, she had little idea that the story might lead to the end of her journalism career, the loss of her home, and separation from her family.

Yildiz, then a reporter for the Turkish news site T24, was the first to report that local prosecutors in southern Turkey had intercepted a convoy of trucks bearing Turkish arms heading for Syria.

The disclosure had put Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s government in an awkward position, since Turkey had long denied that it was sending aid to rebels fighting Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s government.

When Yildiz later published footage of the of the prosecutors being put on trial, she herself was sued by the government. In May 2016, she was stripped of the guardianship of her two young children and sentenced to 20 months in jail – a decision which was stayed pending the approval of an appellate court.

But then Turkey’s climate for the press, already bad, took a sharp turn for the worse. In July 2016, a group of dissident Turkish military officers attempted to overthrow Erdogan in a coup. When it failed, Erdogan’s response was ferocious. Tens of thousands of soldiers and government workers were purged and media outlets viewed as critical of Erdogan were shuttered. In the aftermath, more than 300 journalists were arrested. As for Yildiz, after security forces appeared at her home with a warrant for her arrest, she and daughters Emine, then 7, and the infant Zehra, went into hiding. They lived in secrecy in a single room for five months.

“I could not continue living in this one bedroom,” she says. “It begins to affect you psychologically. Every time the door is knocked, you would think it was the police.”

In November 2016, Yildiz left both girls with their grandparents and fled across the border to a refugee camp in Greece. She was quickly given asylum in Canada and moved to Toronto by herself. In 2018, her eldest daughter Emine joined there, but Zehra, now 3, remains in Turkey.

Now working in a pizzeria in Toronto, Yildiz, 39, spoke with Global Journalist’s Lara Cumming about her career and the high personal cost of doing independent journalism in Turkey. Below, an edited version of their interview:

Global Journalist: How did you get into journalism?

Arzu Yildiz: After I finished school, I was a court reporter for a long time. I reported on the police and the justice system. I never cared about politics or the government I only focused on justice. I worked with Taraf [a liberal Turkish national newspaper] for over five years. After this I tried doing journalism independently at T24 for a couple of years.

For two months I worked [for a newspaper] close to Erdogan’s party, a big newspaper called Türkiye. But they censored my news. After that I quit. All this time, I may be the only woman court reporter who knows the law as much as a prosecutor or judge. When I was doing journalism, I was studying the law. Some prosecutors didn’t read as much as me. I was interested in not only the justice system of Turkey but also the justice [systems] of the world.

GJ: How did you know it was time to leave Turkey?

Yildiz: Two days after the July 15th [2016] coup attempt, the police came to my house. After the coup attempt, a lot of [arrested] people faced torture and no one would have written about it. If I continued to be a court reporter, I would write what is really going on in court and why people were detained.

After the police came, I lived an underground life for five months. One of my daughters was just 7 months old and the other was 7 years old. We lived in one room together.

[Later] I realized that this is no life. I tried to give them a chance. I could not continue living in this one bedroom. It begins to affect you psychologically. Every time the door is knocked, you would think it was the police.

GJ: Are you still in contact with your family in Turkey?

Yildiz: The little one doesn’t know me or who I am, she has no mother. She is in Turkey with my parents. I saw her birthday only through video. I have no contact with her, no telephone calls, no nothing. I divorced my husband and I have no contact with my mother and father also. They lost their daughter too. I didn’t only lose mine.

The [eldest] one had a U.S. visa before. She came to the U.S.A. alone [in September 2018]. One of my friends took her to the Canadian border. My other daughter had no chance to come to Canada. They will not give her a passport because of me.

My mother is 73-years old, when this situation is over I don’t know what will happen. I may never see them [my parents] again. The Canadian government will not issue them a visa.

Some say: “Meet them in another country.” They must think I’m very rich. I cannot go to Ottawa right now because I am working two jobs and only just paying my rent. All of the family is affected, three generations. My oldest daughter, who is with me, always asks why we are separated from her grandparents. My children referred to my mother as their mother.

GJ: What issues did you see with journalism in Turkey before you left?

Yildiz: My goal as a journalist was seeking truth. We have no goals to be heroes or to be famous. We are not actors. We are not singers. We are journalists. The goal is to tell what’s right and who the heroes are through our stories. And if the world starts talking about them, I can say I did my job well.

My problem is with the bureaucracy. I cannot trust politicians, but I should be able to trust the judges. For example, if people drive unsafely in Canada they will be punished by the justice system. They are not scared of the politicians, they are scared only of the justice system. In Turkey there is no trust of the judicial system.

I am not a religious person and I do not believe in any religion. Religion and racism are just the tools the politicians use for their benefit. I believe only in humanity. If I am dying, I do not want someone to define me only as a Turkish journalist but as a human. I do not care how a person looks or what they believe, only if they are honest. If you are a court reporter – like me – your only focus is if someone is innocent or if they are a criminal.

GJ: Do you have any plans to return to Turkey?

Yildiz: Before I came to Canada, I spent time in a refugee camp. The real meaning of being a refugee is not only the loss of the country, but loss of a family and being alone. I came with one t-shirt and no shoes. Believe me, I lost the shoes in the refugee camp.

I came with only cheap things. No mobile phone no nothing. Maybe $200 and that’s it. I will not be able to return to Turkey as they will put me in prison.

GJ: Has the pursuit of your work been worth it? You have done such brave work but also lost so much.

Yildiz: I lost so many things, no one can imagine. If I had the chance to return to the past, I would do this again. But one thing is broken: my heart.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/6BIZ7b0m-08″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship partner Global Journalist is a website that features global press freedom and international news stories as well as a weekly radio program that airs on KBIA, mid-Missouri’s NPR affiliate, and partner stations in six other states. The website and radio show are produced jointly by professional staff and student journalists at the University of Missouri’s School of Journalism, the oldest school of journalism in the United States. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Don’t lose your voice. Stay informed.” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship is a nonprofit that campaigns for and defends free expression worldwide. We publish work by censored writers and artists, promote debate, and monitor threats to free speech. We believe that everyone should be free to express themselves without fear of harm or persecution – no matter what their views.

Join our mailing list (or follow us on Twitter or Facebook). We’ll send you our weekly newsletter, our monthly events update and periodic updates about our activities defending free speech. We won’t share, sell or transfer your personal information to anyone outside Index.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][gravityform id=”20″ title=”false” description=”false” ajax=”false”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content”][vc_column][three_column_post title=”Global Journalist / Project Exile” full_width_heading=”true” category_id=”22142″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

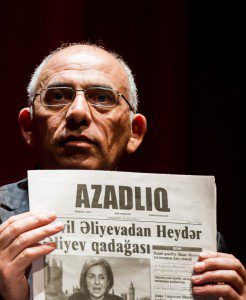

Rahim Haciyev, then acting editor-in-chief of Azerbaijani newspaper Azadliq in accpting the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Journalism Award in 2014 (Photo: Alex Brenner for Index on Censorship)

On the night that Rahim Haciyev accepted the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Guardian Journalism Award, he held aloft a copy of the paper that persevered despite assaults from the government whose misdoings it exposed. It was March 2014 and Haciyev, acting editor-in-chief of independent Azerbaijani newspaper Azadliq, was on stage in London. Triumphantly, he declared: “The newspaper team is determined to continue this sacred job – serving the truth. Because this is the meaning of what we do and the meaning of our lives.”

Four months later, this mission was compromised by threats, arrests and financial constraints for reporting on government corruption. It was not the first time Azadliq experienced economic pressure from its government-backed distributors under Azerbaijan’s now four-term leader, Ilham Aliyev. Aliyev has long faced accusations of authoritarian rule and suppressing dissent since taking office in 2003.

But months of fines surpassing £50,000 and mounting arrests overwhelmed the paper, which suspended its print edition in July 2014. Among other members of civil society and the independent media, Haciyev’s colleague, columnist Seymur Hezi, remains imprisoned for “aggravated hooliganism” after defending himself from a physical assault. The public’s widespread protest went unheard by the government.

As of this year, Reporters Without Borders’ Press Freedom Index has documented that 165 journalists are currently imprisoned in Azerbaijan. Monthly, the Mapping Media Freedom database features reports on the former Soviet republic’s assault on dissenting speech. In July 2018 alone, MMF documented four opposition websites blocked by the government for spreading misinformation, two editors of independent news outlets questioned by authorities and one journalist arrested for disobeying the police.

In December 2017 a high court in Azerbaijan upheld the blockage of five independent media organisations’ websites, including Azadliq.info, active since March 2017. Haciyev criticised this move as further inhibiting the Azerbaijani people’s ability to access objective information.

Living in exile in western Europe since 2017, he told Index: “Four employees of our site are in prison. Our employees who are in prison were accused of hooliganism and illegal financial transactions. All of them were arrested on trumped-up charges. All the charges were fabricated.”

Haciyev oversees the paper’s Facebook page from abroad, while the website remains updated and accessible to readers outside Azerbaijan. Regarding the current status of free expression back home, he said: “The situation in the country is very difficult. The authorities continue to oppress democratically minded people. Arrests of political activists and journalists continue.”

Haciyev spoke with Index’s Shreya Parjan about the ongoing situation.

Index: Is Azadliq alone as a target? Why was the publication perceived as such a threat to the government?

Hajiyev: We can not say that only Azadliq was subjected to repression. Azerbaijani authorities are very corrupt and cannot tolerate criticism from their opponents. The corrupt and repressive regimes around the world suppress freedom of speech. In this regard, the Azerbaijani authorities, especially in recent years, have been in the ranks of the world’s most repressive.

Index: What ultimately made you decide to leave Azerbaijan and how difficult was the process?

Hajiyev: The newspaper ceased its operations in September 2012. The authorities have not allowed Azadliq to be published. At that time, they left the site of the newspaper. I stayed in the country for some time. I regret that I had to leave the country after the very strong pressure of the authorities. My colleague continued to lead the website and the Facebook page of the newspaper. Of course it is a difficult process. To be forced to leave the country [is a] very unpleasant affair. I had to endure a lot of trouble. Nevertheless, I continued the business.

Index: While in exile, how have you been able to continue your work and advocate for change?

Hajiyev: At this time in exile, I continue to guide the website and the Facebook page of the newspaper. Being outside the country, I actively use social networking. On the one hand, I gather information, on the other hand, I distribute it. Social networks help organise and conduct work. Our Facebook page is one of the most popular in the country, and I am proud of our achievement.

Index: Could you identify any supportive communities you have encountered with while in exile? What obligation do foreign journalists have to collaborate and support one another in times of crisis?

Hajiyev: Communication between journalists who are abroad is important. To share experiences and information would be useful. It would be very nice to be able to communicate work by local journalists.

Index: How does the crackdown on digital freedom oppose the government narrative of a modern, free Azerbaijan?

Hajiyev: In Azerbaijan, there is a political regime that strongly suppresses freedom of speech. According to the index of freedom of speech, composed Reporters Without Borders, Azerbaijan occupies the 163rd place. Azerbaijan is currently undergoing one of the most difficult times in its history. The rights and freedoms of citizens have long been of nominal character. There are now more than 160 political prisoners.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content”][vc_column][three_column_post title=”Global Journalist / Project Exile” full_width_heading=”true” category_id=”22142″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

In 2009, incumbent president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad won Iran’s highly contested election against Mir-Hossein Mousavi, which led to public outrage and the formation of the Green Movement, filling the streets with demonstrations calling for Ahmadinejad’s ouster. For the next two years, Iranian authorities ran a campaign of jailing journalists and political opponents. Journalist Omid Rezaee was one such detainee.

The Iranian-born mechanical engineering student was the editor-in-chief of Fanous, a student magazine which was banned for standing with the Green Movement. Rezaee was arrested in October 2011.

In 2012 he fled to Iraq, and in 2015 he made his way to Germany. In February 2017 he started his own multilingual website, Perspective Iran, where news about Iran is mainly reported in German. He has also been working as a freelance writer within German media outlets since he was exiled. Rezaee aims to show the many hidden aspects of Iran and the nature of the everyday lives of its people.

Index on Censorship: You became a journalist at a very young age. What made you choose this career path so early?

Omid Rezaee: Storytelling excites me and has done so since childhood. It’s the first thing I learned about myself. First by reading stories – whether journalistic and media stories or fiction – and then by telling stories. When I was 10, I founded a small magazine in the primary school which failed after only two editions. By 15, I founded the second one in the first year of high school. This one was published for one year and by 17 I founded the next one which was being distributed in all high schools of our town and which brought me to the attention of the authorities for the first time. But I still think this was worth all the troubles because it gave me the opportunity to narrate stories. It’s the most delightful thing in this world.

Index: Why did you leave Iran?

Omid: The idea of leaving the country popped in my mind while I was sitting alone in a cell for days and nights without being able to see or talk to anyone. I was asking myself for how much longer I can bear this situation. When I was sentenced to two years in prison, I had to think about it more seriously. There are many reasons – both private and political – which led to my decision to leave the country. I would say the most important one – which still applies – is that I missed my freedom. First and foremost the freedom of speech, but it’s also freedom of lifestyle.

Index: Walk us through your migration on foot to Iraq.

Omid: Apart from the dangers and physical and technical things, I would never ever forget the moment I crossed the border as if it was the end of the earth. I would never forget how I looked back to the soil, the ground which used to be my homeland. I guess there is a huge difference when you leave the country by a plane and don’t see that “border”. And when you cross it on foot and you know, you won’t be back soon. This grieves you deeply.

Index: You are an active writer online. How do you think the internet has changed journalism?

Omid: I’ve started a professional career online and I am now studying digital journalism. By now it’s part of me and I’m part of the digital world. Honestly, I have no clue how the professional journalism used to work before it was online. But the fact that I can still report on Iran and the Middle East, even though I’ve been away for years, is directly due to the internet and online world. Apart from all the troubles we’re facing, we are closer to each other because of the internet. And more important: the digital world gives us – the journalists – more possibilities to strive against illegitimate authorities all over the world.

Index: How have you settled into life away from home?

Omid: It’s not true if I say I don’t miss my hometown, the city I studied in and the people I loved – or still love – and who love me. But the bottom line is that home is where one is free, where one can develop himself and live with dignity. I have a lot of good memories of Iran and I deeply miss a lot of people there, but I never considered Iran as a home, and it’s the same here in Germany. My home is my language. I don’t mean Farsi; I love German just as much my mother tongue, and this applies to the English language and the languages I’m learning right now. My home is the story I’m telling and I’m settling into my new life by telling stories. I am firmly convinced that only storytelling can rescue us.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row disable_element=”yes”][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/6BIZ7b0m-08″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship partner Global Journalist is a website that features global press freedom and international news stories as well as a weekly radio program that airs on KBIA, mid-Missouri’s NPR affiliate, and partner stations in six other states. The website and radio show are produced jointly by professional staff and student journalists at the University of Missouri’s School of Journalism, the oldest school of journalism in the United States. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content”][vc_column][three_column_post title=”Global Journalist / Project Exile” full_width_heading=”true” category_id=”22142″][/vc_column][/vc_row]