Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

A Russian fan at the Euro 2020 match between Belgium and Russia. Stanislav Krasilnikov/Tass/PA Images

In celebration of one of football’s biggest international tournaments, here is Index’s guide to the free speech Euros. Who comes out on top as the nation with the worst record on free speech?

It’s simple, the worst is ranked first.

We continue today with Group B, which plays the deciding matches of the group stages today.

Unlike their relatively miserable performances on the football pitch, Russia can approach this particular contest as the clear favourites.

The group would be locked up after the first two games, with some sensational play from their three talismans: disinformation, oppressive legislation and attacks on independent media.

Russian disinformation, through the use of social media bots and troll factories, is well known, as is their persistent meddling in foreign elections which infringes on the rights of many to exercise their right to vote based on clear information.

Putin’s Russia has increased its attacks on free speech ever since the 2011 protests over a flawed election process. When protests arose once again all over the country in January 2021 over the detention of former opposition leader Alexei Navalny, over 10,000 people were arrested across the country, with many protests violently dispersed.

Police in the country must first be warned before a protest takes place. A single-person picket is the only form of protest that does not have this requirement. Nevertheless, 388 people were detained in Russia for this very act in the first half of 2020 alone, despite not needing to notify the authorities that eventually arrested them.

Human rights organisation, the Council of Europe (COE), expressed its concerns over Russian authorities’ reactions to the Navalny protests.

Commissioner Dunja Mijatović said: “This disregard for human rights, democracy and the rule of law is unfortunately not a new phenomenon in a country where human rights defenders, journalists and civil society are regularly harassed, including through highly questionable judicial decisions.”

Unfortunately, journalists attempting to monitor these appalling free speech violations face a squeeze on their platforms. Independent media is being deliberately targeted. Popular news site Meduza, for example, is under threat from Russia’s ‘foreign agents’ law.

The law, which free expression non-profit Reporters Without Borders describes as “nonsensical and incomprehensible”, means that organisations with dissenting opinions receiving donations from abroad are deemed to be “foreign agents”.

Those who do not register as foreign agents can receive up to five years’ imprisonment.

Being added to the register causes advertisers to drop out, meaning that revenue for the news sites drops dramatically. Meduza were forces to cut staff salaries by between 30 to 50 per cent.

Belgium is relatively successful in combating attacks on free speech. It does, however, make such attacks arguably more of a shock to the system than it may do elsewhere.

The coronavirus pandemic was, of course, a trying time for governments everywhere. But troubling times do not give leaders a mandate to ignore public scrutiny and questioning from journalists.

Alexandre Penasse, editor of news site Kairos, was banned from press conferences after being accused by the prime minister of provocation, while cartoonist Stephen Degryse received online threats after a cartoon that showed the Chinese flag with biohazard symbols instead of stars.

Incidents tend to be spaced apart, but notable. In 2020, journalist Jérémy Audouard was arrested when filming a Black Lives Matter protest. According to the Council of Europe “The policeman tried several times to prevent the journalist, who was showing his press card, from filming the violent arrest of a protester lying on the ground by six policemen.”

There is an interesting debate around holocaust denial, however and it is perhaps the issue most indicative of Belgium’s stance on free speech.

Holocaust denial, abhorrent as it may be, is protected speech in most countries with freedom of expression. It is at least accepted as a view that people are entitled to, however ridiculous and harmful such views are.

The law means that anyone who chooses to “deny, play down, justify or approve of the genocide committed by the German National Socialist regime during the Second World War” can be imprisoned or fined.

Belgium has also considered laws that would make similar denials of genocides, such as the Rwandan and Armenian genocides respectively, but was unable to pursue this due to the protestations of some in the Belgian senate and Turkish communities. It could be argued that in some areas, it is hard to establish what constitutes as ‘denial’, therefore, choosing to ban such views is problematic and could set an unwelcome precedent for future law making regarding free speech.

Comparable legal propositions have reared over the years. In 2012, fines were introduced for using offensive language. Then mayor Freddy Thielemans was quoted as saying “Any form of insult is from now on [is] punishable, whether it be racist, homophobic or otherwise”.

Denmark has one of the best records on free speech in the world and it is protected in the constitution. It makes a strong case to be the lowest ranked team in the tournament in terms of free speech violations. It is perhaps unfortunate then, that they were drawn in a group with their fellow Scandinavians.

Nevertheless, no country’s record on free speech is perfect and there have been some concerning cases in the country over the last few years.

2013 saw a contentious bill approved by the Danish Parliament “reduced the availability of documents prepared”, according to freedominfo.org. Essentially, it was argued that this was a restriction of freedom of information requests which are vital tool for journalists seeking to garner correct and useful information.

Acts against freedom of speech tend to be individual acts, rather than a persistent agenda.

Impartial media is vital to upholding democratic values in a state. But, in 2018, public service broadcaster DR was subjected to a funding cut of 20 per cent by the right-wing coalition government.

DR were forced to cut around 400 jobs, according to the European Federation of Journalists, an act that was described as “revenge” at the time.

There have been improvements elsewhere. In 2017, Denmark scrapped its 337-year-old blasphemy law, which previously forbade public insults of religion. At the time, it was the only Scandinavian country to have such a law. According to The Guardian, MP Bruno Jerup said at the time: “Religion should not dictate what is allowed and what is forbidden to say publicly”.

The change to the law was controversial: a Danish man who filmed himself burning the Quran in 2015 would have faced a blasphemy trial before the law was scrapped.

In 2020, Danish illustrator Niels Bo Bojesen was working for daily newspaper Jyllands-Posten and replaced the stars of the Chinese flag with symbols of the coronavirus.

Jyllands-Posten refused to issue the apology the Chinese embassy demanded.

The Council of Europe has reported no new violations of media freedom in 2021.

A good record across the board, Finland is internationally recognised as a country that upholds democracy well.

Index exists on the principle that censorship can and will exist anywhere there are voices to be heard, but it wouldn’t be too crass of us to say that the world would be slightly easier to peer through our fingers at if its record on key rights and civil liberties were a little more like Finland’s.

It is joint top with Norway and Sweden of non-profit Freedom House’s Global Freedom Index of 2021, third in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index 2020, sixth in The Economist’s Democracy Index 2020 and second in RSF’s World Press Freedom Index.

Add that together and you have a country with good free speech protections.

That is not to say, though, that when cases of free speech violations do arise, they can be very serious indeed.

In 2019, the Committee to Project Journalists (CPJ) called for Finnish authorities to drop charges against journalist Johanna Vehkoo.

Vehkoo described Oulou City Councilor Junes Lokka as a “Nazi clown” in a private Facebook group.

A statement by the CPJ said: “Junes Lokka should stop trying to intimidate Johanna Vehkoo, and Finnish authorities should drop these charges rather than enable a politician’s campaign of harassment against a journalist.”

“Finland should scrap its criminal defamation laws; they have no place in a democracy.”

Indeed, Finnish defamation laws are considered too harsh, as a study by Ville Manninen on the subject of media pluralism in Europe, found.

“Risks stem from the persistent criminalization of defamation and the potential of relatively harsh punishment. According to law, (aggravated) defamation is punishable by up to two years imprisonment, which is considered an excessive deterrent. Severe punishments, however, are used extremely rare, and aggravated defamation is usually punished by fines or parole.”

The study also spoke of another problem, that of increased harassment or threats towards journalists.

Reporter Laura Halminen had her home searched without a warrant after co-authoring an article concerning confidential intelligence.

Group F[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also like to read” category_id=”8996″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”116328″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship was established to provide a voice for dissidents living either under authoritarian regimes or in exile. Throughout our history extraordinary people have written for us and we have campaigned for their freedom. Every time Index seeks to intervene there is obviously a consideration made about who we seek to shine a light on and which regimes are of concern but the reality is we don’t get to choose dissident leaders and we don’t get to choose who inspires a movement. Our role is simple – we are here to campaign for equal access to Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. We may not like the actions of some dissidents, we may not like how they have used their rights to free expression – but we exist to ensure that they have that right.

Index operates from a position of luxury, from the security of a democratic country. Our human rights are protected in law. For far too many people in the world that is not the case. Which brings me to the case of Alexei Navalny – we may find his comments as a younger man abhorrent, but his actions as a dissident leader cannot be questioned. His ability to inspire a nation to challenge an authoritarian regime is extraordinary. And the fact that he has nearly lost his life in an attempted chemical poisoning is beyond doubt. Navalny is a political prisoner. He is a dissident. He deserves our solidarity.

Index stands with Navalny.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

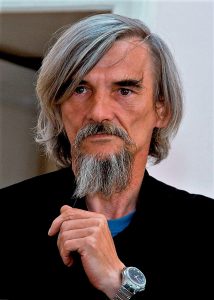

Russian historian Yuri Dmitriev, who has been imprisoned following research into murders committed by Stalin. Credit: Mediafond/Wikimedia

Western democracies have expressed concern and outrage, at least verbally, over the Novichok poisoning of Alexei Navalny—and this is clearly right and necessary. But much less attention is being paid to the case of Yuri Dmitriev, a tenacious researcher and activist who campaigned to create a memorial to the victims of Stalinist terror in Karelia, a province in Russia’s far northwest, bordering Finland. He has just been condemned on appeal by the Supreme Court of Karelia to thirteen years in a prison camp with a harsh regime.

The hearing was held in camera, with neither him nor his lawyer present. For this man of sixty-four, this is practically equivalent to a death sentence, the judicially sanctioned equivalent of a drop of nerve agent.

After an initial charge of child pornography was dismissed, Yuri Dmitriev was convicted of sexually assaulting his adoptive daughter. These defamatory charges appear to be the latest fabrication of a legal system in thrall to the FSB—a contemporary equivalent, here, of the nonsensical slander of “Hitlerian Trotskyism” that drove the Great Terror trials. It is these same charges, probably freighted with a notion of Western moral decadence in the twisted imagination of Russian police officers, that were brought in 2015 against the former director of the Alliance Française in Irkutsk, Yoann Barbereau.

I met Yuri Dmitriev twice: the first time in May 2012, when I was planning the shooting of a documentary on the library of the Solovki Islands labor camp, the first gulag of the Soviet system; and the second in December 2013, when I was researching my book Le Météorologue (Stalin’s Meteorologist, 2017), on the life, deportation, and death of one of the innumerable victims murdered by Stalin’s secret police organizations, OGPU and NKVD.

In both cases, Dmitriev’s help was invaluable to me. He was not a typical historian. At the time of our first meeting, he was living amid rusting gantries, bent pipes, and machine carcasses, in a shack in the middle of a disused industrial zone on the outskirts of Petrozavodsk—sadly, a very Russian landscape. Emaciated and bearded, with a gray ponytail, he appeared a cross between a Holy Fool and a veteran pirate—again, very Russian. He told me how he had found his vocation as a researcher—a word that can be understood in several senses: in archives, but also on the ground, in the cemetery-forests of Karelia.

In 1989, he told me, a mechanical digger had unearthed some bones by chance. Since no one, no authority, was prepared to take on the task of burying with dignity those remains, which he recognized as being of the victims of what is known there as “the repression” (repressia), he undertook to do so himself. Dmitriev’s father had then revealed to him that his own father, Yuri’s grandfather, had been shot in 1938.

“Then,” Dmitriev told me, “I wanted to find out about the fate of those people.” After several years’ digging in the FSB archive, he published The Karelian Lists of Remembrance in 2002, which, at the time, contained notes on 15,000 victims of the Terror.

“I was not allowed to photocopy. I brought a dictaphone to record the names and then I wrote them out at home,” he said. “For four or five years, I went to bed with one word in my head: rastrelian—shot. Then, I and two fellow researchers from the Memorial association, Irina Flighe and Veniamin Ioffe (and my dog Witch), discovered the Sandarmokh mass burial ground: hundreds of graves in the forest near Medvejegorsk, more than 7,000 so-called enemies of the people killed there with a bullet through the base of the skull at the end of the 1930s.”

Among them, in fact, was my meteorologist. On a rock at the entrance to this woodland burial ground is this simple Cyrillic inscription: ЛЮДИ, НЕ УБИВАЙТЕ ДРУГ ДРУГА (People, do not kill one another). No call for revenge, or for putting history on trial; only an appeal to a higher law.

Memorials to the victims of Stalin’s Terror at Krasny Bor, Karelia, 2018; the remains of more than a thousand people shot between 1937 and 1938 at this NKVD killing field were identified by Dmitriev, using KGB archival records

Not content to persecute and dishonor the man who discovered Sandarmokh, the Russian authorities are now trying to repeat the same lie the Soviet authorities told about Katyn, the forest in Poland where NKVD troops executed some 22,000 Poles, virtually the country’s entire officer corps and intelligentsia—an atrocity that for decades they blamed on the Nazis. Stalin’s heirs today claim that the dead lying there in Karelia were not victims of the Terror but Soviet prisoners of war executed during the Finnish occupation of the region at the beginning of World War II. Historical revisionism, under Putin, knows no bounds.

I am neither a historian nor a specialist on Russia; what I write comes from the conviction that this country, for which I have a fondness, in spite of all, can only be free if it confronts its past—and to do this, it needs courageous mavericks like Yuri Dmitriev. And I write from the more personal conviction that he is a brave and upright man, one whom Western governments should be proud to support.

This article was translated from the French by Ros Schwartz. It was originally published on the New York Review of the Books here under the headline Yuri Dmitriev: Historian of Stalin’s Gulag, Victim of Putin’s Repression.

Read our article exploring Dmitriev’s case and how history is being manipulated and erased here.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”114819″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]On 9 August, Belarus went to the polls to elect their president. Alexander Lukashenko, who has been in power since 1994, was seeking a fifth term.

When the result was announced, Lukashenko had won 80% of the vote. However, the Belarusian people believed the election was rigged and took to the streets in their thousands to protest peacefully.

One of those protesting was 73-year-old great grandmother Nina Bahinskaya, who has become a famous face on the streets of Minsk as she squares up to Lukashenko’s riot police.

She has been arrested and fined half of her pension but still comes back for more.

Index on Censorship’s associate editor Mark Frary spoke with her to find out how she became an unlikely protestor, why she always carries a flag and whether she fears for her safety in the face of police brutality.

With thanks to Franak Viacorka, Radio Free Europe, Euroradio and Alina Stefanovic (interpreter).[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/4Ap8jtyRVKc”][/vc_column][/vc_row]