Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

In 2005 Flemming Rose commissioned the cartoons of the prophet Mohammed that sparked protests and riots across the world.

In 2005 Flemming Rose commissioned the cartoons of the prophet Mohammed that sparked protests and riots across the world.

In an exclusive book extract, Rose explains why bans on hate speech across Europe are based on a false understanding of its role in the Holocaust

Besides the issue of self-censorship, the debate ensuing from the [Danish] cartoons revealed a number of fractures in European culture and self-understanding. One of these arose from the trauma of the Second World War, an event Europe at all costs wished to avoid repeating. The lesson learned from the Jewish Holocaust was that words could kill, and hateful words would beget hateful actions. It was widely held that if only the Weimar government had clamped down on the National Socialists’ verbal persecution of the Jews in the years prior to Hitler’s rise to power, or if the Nazis had been prevented from pursuing their propaganda of hatred following 1933, then the Holocaust would never have happened. Proponents of this view saw a parallel between unfettered freedom of speech, demonisation of the Jews in Nazi propaganda, and their subsequent extinction in the concentration camps. It was the same train of thought that prompted Denmark’s former foreign minister, Per Stig Møller, to warn in 2009 that free speech could be abused to incite violence. “We see it today in the message being sent out by Osama bin Laden. And we saw it in Germany, where anti-Semitic rhetoric eventually led to die Endlösung, the Final Solution, by which six million Jews were killed,” he wrote in a newspaper article.

The assertion that Nazi propaganda had played a significant role in mobilising anti-Jewish sentiment is irrefutable. But to claim that the Holocaust could have been prevented if only anti-Semitic speech and Nazi propaganda had been banned was to stretch a point. Anti-Semitism in the Weimar Republic sparking off violence and calls for Jews to be deprived of all rights was one thing. Another was Nazi apartheid, the exclusion of Jews from German society under Hitler in the 1930s, the annulment of Jewish civil rights, the Kristallnacht, or Night of Broken Glass, and the pogroms. Still another was the Holocaust. What unites them, however, is that at no point did freedom of speech exist unhindered in Germany in the period in question.

In the wake of the Holocaust, European democracies concluded that a ban on hate speech could prevent, or at least contain, racist violence and killings. The Allies duly enforced legislation to that effect on Germany and Austria in the immediate aftermath of war, believing it to be insurance against a repeat Holocaust. History, however, provided no evidence by which to legitimise such reasoning. Nonetheless, it was a logic that formed the basis of international efforts towards the protection of human rights in the post-war decades. Jewish organisations also played an active role in the process. Presumably, they had little idea of how far it would lead.

The ball began rolling with the UN International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights in 1965, which entered into force a year later, and the UN Convention on Racial Discrimination of 1965, which took effect in 1969. Committees were set up by the UN to monitor the extent to which member states upheld the conventions. A couple of decades previously, following its inception in 1949, the Council of Europe had taken steps towards establishing the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights, the world’s first human rights treaty, taking effect in 1953. The European Court of Human Rights was encharged by the Council of Europe with monitoring and dealing with complaints by citizens who believed their rights according to the Convention to have been violated within a member state. In 1998, the institution was made permanent. The number of members of the Council of Europe grew in the wake of the Cold War to 47 countries. A commensurate rise occurred in the number of complaints to the Court: from 138 in 1955, the figure sky-rocketed to some 41,000 in 2005. The Court was not a court of appeal. It was not empowered to nullify the ruling of courts of law at the national level, but it could order a member state to align its practice with the Convention in the case that it ruled in favour of a plaintiff.

This was a quite momentous and indeed laudable development. For the first time, individuals were accorded global rights transgressing national boundaries. After the millennium, however, the constraints on free speech enforced by the conventions on national legislations were to become a significant instrument for grievance fundamentalists and for authoritarian regimes which made use of them to justify oppression of alternative thinkers and of ethnic and religious minorities. This tended to occur with particular reference to two articles: Article 20, paragraph 2 of the Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and Article 4 of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination.

The first of these runs as follows: “Any advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence shall be prohibited by law.” The second, taking as its point of departure a rather broad definition of racial discrimination, declared that the state: “Shall declare an offence punishable by law all dissemination of ideas based on racial superiority or hatred, incitement to racial discrimination [. . .] against any race or group of persons of another colour or ethnic origin.” Moreover, states were obliged to prohibit organisations and propaganda activities promoting or inciting racial discrimination, just as participation in such organisations or activities was to be made punishable by law.

The wording was awkward and technical, though the intention was clear: words and actions were to be considered parallel. There was to be no principle difference between saying something discriminatory and performing discriminatory actions. With time, definitions of racism and discrimination widened, the distinction between words and actions becoming commensurately more blurred. With a public sector growing by the year, the welfare state was afforded wide-reaching privileges and the responsibility of ensuring a new form of equality among citizens. Individuals were no longer simply to enjoy equal opportunities, but were to be ensured equal results. In the welfare state, there were to be no differences, and the rights of the individual were to give way to those of the community.

Things came to a head with immigration to Europe from the Islamic world in particular. European welfare states suddenly found themselves under pressure. The new diversity, the gaps that emerged in cultures and religions and ways of living meant on the one hand that the welfare state had to impose demands on its new citizens to make them adapt to the norms of the society and thereby ensure a continued community of values. On the other hand, the welfare state was forced to take measures against those of its indigenous citizens who expressed discontent with these new demographic developments and who did so in a language it considered to be a threat to social stability and the right not to be subjected to utterances of a discriminatory nature. Wide-reaching freedom of speech essentially ran against the grain of the ideology of the welfare state in a multicultural society.

The grievance lobby in the UN, the EU and the human rights industry was directed by a notion that criminalisation of racist utterances, so-called hate speech, would lead to racism being eradicated. They drew up a succession of reports urging member states to prosecute and sentence perpetrators of hate speech to a much greater degree than before. The grievance lobby wanted the definition of racism expanded so as to encompass still more groups within society. Their whole perspective was driven by the notion of insult: theirs was a world all about identifying the victims of freedom of speech and those guilty of its abuse. Those who defended the offended could adorn themselves with the halos of justice. If they who offended were found guilty and punished, a good deed had been done for a better world.

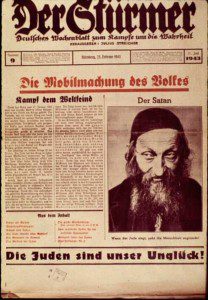

The modern dispute as to the boundaries of free speech began with the Nuremberg trials of 1945- 46 in which 24 Nazis stood accused for their roles in the genocide of the Second World War. The trials established that there were clear ties between the Nazis’ mobilisation of the media, which in words and pictures had demonised and blackened the character of the Jews, and the subsequent Holocaust. Julius Streicher, former editor of the anti-Semitic tabloid Der Stürmer, was among those the tribunal condemned to death. During the process, Streicher was singled out as “Jew-Baiter Number One”. The judgment against him ran:

The modern dispute as to the boundaries of free speech began with the Nuremberg trials of 1945- 46 in which 24 Nazis stood accused for their roles in the genocide of the Second World War. The trials established that there were clear ties between the Nazis’ mobilisation of the media, which in words and pictures had demonised and blackened the character of the Jews, and the subsequent Holocaust. Julius Streicher, former editor of the anti-Semitic tabloid Der Stürmer, was among those the tribunal condemned to death. During the process, Streicher was singled out as “Jew-Baiter Number One”. The judgment against him ran:

“In his speeches and articles, week after week, month after month, he infected the German mind with the virus of anti-Semitism and incited the German people to active persecution [. . .] Streicher’s incitement to murder and extermination at the time when Jews in the East were being killed under the most horrible conditions clearly constitutes persecution on political and racial grounds in connection with war crimes as defined by the Charter, and constitutes a crime against humanity.”

This take on the genesis of the Holocaust formed the basis of an understanding of the relationship between words and actions that led increasingly to the outlawing of verbal affront. What was ignored in such cases, however, was the fact that Streicher’s and other Nazis’ Jew-baiting occurred in a society utterly devoid of freedom of speech: under Hitler, no freedom existed by which to counter the witch-hunt against the Jewish community. Germany was ruled by a tyranny of silence.

The premise came out of an idea characterising totalitarian societies laid out in George Orwell’s masterful novel 1984. The verbal hygiene of the totalitarian state was to ensure the development of the ideal society. Words established what they denoted; banning mention of entities and phenomena meant they would cease to exist. Thus, language became an instrument for creating the world in one’s own image: war is peace, freedom is slavery, ignorance is strength.

In the Soviet Union, the machinery of propaganda vanished away nationalism; ethnic and religious tensions –– with the exception of isolated, post-capitalist pockets that would soon be swallowed up by communism –– were likewise non-existent. In books and films, art and the media, the magic eraser of the censor wiped out whatever didn’t fit the Marxist-Leninist version of reality. Party Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev believed so devoutly in the orally hygienic, beautified image that at first he was unable to grasp what was happening as national separatist movements rose up to eventually condemn the Soviet Union to history’s dump. The notion that social evils could be eradicated by prohibiting certain kinds of utterance was completely in tune with the self-image of Soviet ideology. In a dictatorship, no principle distinction exists between words and actions.

The claim that the Holocaust was the result of Nazi “abuse of freedom of speech” failed to distinguish between the totalitarian society, in which no freedoms existed by which to counter, ridicule and expose racist propaganda, and, by contrast, the open, democratic society whose citizens were at liberty to say whatever they wanted to uncover the lies of National Socialism, a society in which the public space was an open market of competing ideas and in which intimidation of individuals and groups within society never went unchallenged.

In Weimar Germany, insulting communities of faith –– Protestant, Catholic or Jew –– was a punishable offence commanding up to three years’ imprisonment. Similarly, the dissemination of false rumour with the intention of degrading or showing contempt for other individuals could result in two years. Incitement to class warfare or acts of violence towards other social classes was also prohibited by law, likewise punishable by up to two years behind bars. It was a piece of legislation to which the Jewish community often sought recourse in order to defend themselves against anti-Semitic attacks. Anti-Semites countered, occasionally with success, by claiming their attacks on Jews were not incitement to class hatred, but were instead aimed at the Jewish “race” and therefore not an offence.

The notion that freedom of speech was unconstrained in Weimar Germany was a fallacy. The reality of the matter was that political violence flourished without intervention by the authorities. Leading Nazis such as Joseph Goebbels, Theodor Fritsch and Julius Streicher were all prosecuted for their anti-Semitic utterances. Streicher served two prison sentences. Rather than deterring the Nazis and preventing anti-Semitism, the many court cases served as effective public relations machinery for Streicher’s efforts, affording him the kind of attention he never would have found had his racist utterances been made in a climate of free and open debate. Only weeks after Streicher was sentenced to two months imprisonment for anti-Semitism, the Nazis trebled their share of the vote at the state legislature election in Thuringia. One of the charges brought against Streicher and his associate, Karl Holz, concerned Der Stürmer having construed a number of unsolved murders as ritual killings perpetrated by Jews. The second concerned claims published in the paper that the Jewish faith permitted perjury before non-Jewish courts.

Bernhard Weiss, Vice-President of the Berlin police, regularly dragged Goebbels into court on charges of anti-Semitism. In all these cases brought against the future head of Nazi propaganda, the prosecution came out on top, yet according to one observer, in the public eye Weiss consistently ended up looking more like the loser, as Goebbels’ anti-Semitic invective found a platform in the public process.

Bernhard Weiss, Vice-President of the Berlin police, regularly dragged Goebbels into court on charges of anti-Semitism. In all these cases brought against the future head of Nazi propaganda, the prosecution came out on top, yet according to one observer, in the public eye Weiss consistently ended up looking more like the loser, as Goebbels’ anti-Semitic invective found a platform in the public process.

“The Vice-President of police may have been better served by simply allowing the Nazi attacks to echo away in silence,” mused Dietz Bering in an anthology on the Jews of the Weimar Republic.

In April 1932, Nazis plastered the city of Nuremberg with posters proclaiming Die Juden sind unser Unglück! (The Jews are our misfortune). It was the motto of Der Stürmer. To begin with, police refused to remove them, despite a formal complaint being lodged by the Jewish Central Committee. The argument was that the posters could not be considered an incitement to violence, but when the Central Committee went to the authorities in Munich the posters were removed. In October of the same year, a young non-Jewish girl in the northern part of the country died when her Jewish boyfriend tried to help her perform an abortion. The young man tried to get rid of the body by cutting it into pieces and scattering them over a wide rural area. For Der Stürmer, it was a case made in heaven, but when the paper appeared with a detailed description of the events construed as a Jewish ritual murder, the issue was confiscated and the editor responsible later convicted of causing religious affront.

In the period 1923 to 1933, Der Stürmer was either confiscated or its editors taken to court on no fewer than 36 separate occasions. In 1928, the paper and its staff were the subjects of five litigations in the space of 11 days. Proceedings, however, gave the general public the impression that Streicher was more significant than was the case. Those instances where Streicher was sentenced to terms of imprisonment were a golden opportunity for him to portray himself as a victim and martyr. The more charges he faced, the greater became the admiration of his occasions on which he was sent to jail, Streicher was accompanied on his way by hundreds of sympathisers in what looked like his triumphal entry into martyrdom. In 1930, he was greeted by thousands of fans outside the prison, among them Hitler himself. The German courts became an important platform for Streicher’s campaign against the Jews. Some observers suggested that the cases brought against him prompted critics of the Nazis to relax complacently in the faith that the judicial system alone was capable of combating National Socialism.

According to historian Dennis E Showalter, author of a book about Streicher and Der Stürmer during the Weimar Republic, the judicial system found itself ill-equipped to stem the tide of anti-Semitism, though its shortcomings were by no means attributable to a lack of legislation or Nazi bias. ‘The familiar cliché that Weimar’s legal system was not particularly interested in protecting Jews, and avoided doing so when it could, requires significant revision [. . .] The regional legal system included active and potential Nazi sympathisers. Yet in general, the courts of northern Bavaria sustained the Jewish legal position even in one of Nazism’s strongholds,” Showalter stated.

In the view of Alan Borovoy, general counsel of the Canadian Civil Liberties Association (CCLA), in the Weimar Republic in the time leading up to Hitler’s claiming power in 1933, cases were regularly brought against individuals on account of anti-Semitic speech. “Remarkably, pre-Hitler Germany had laws very much like the Canadian anti-hate law. Moreover, those laws were enforced with some vigour. During the 15 years before Hitler came to power, there were more than 200 prosecutions based on anti-Semitic speech [. . .] As subsequent history so painfully testifies, this type of legislation proved ineffectual on the one occasion when there was a real argument for it,” Bovory writes in his 1988 book When Freedoms Collide: The Case for Civil Liberties.

The widely made claim that hate speech against the Jews was a primary factor of the Holocaust has no empirical support. In fact, one might forcefully argue that what paved the way for Holocaust was the ban on hate speech, in so far as it handed Streicher and other Nazis a glorious opportunity to bait the Jewish community in the German courtrooms and in a national press, which otherwise would have spared them precious little ink. For the democrats of the Weimar Republic, a far more effective strategy would have been to address Nazi propaganda in free and open public debate, but in Europe between the wars confidence in free speech was running low.

This is an edited extract from Flemming Rose’s book The Tyranny of Silence. It is its first publication in English.