Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From broadcasting uprisings to employing Russian spies, Radio Free Europe brings news to poorly served regions. In the autumn 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine, Sally Gimson looks at the station’s history and asks if it is still needed today”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Gregory Baldwin / Ikon

In Georgia, the future of Radio Free Europe, and sister station Radio Liberty, is looking precarious. This summer the Georgian government’s central broadcaster shut down two of RFE/RL’s most popular political programmes. The broadcaster said it was part of a wider restructure, but civil society organisations condemned the move and suggested the station wanted to eliminate critical viewpoints. The move and the subsequent outcry highlight the role RFE continues to play, namely to often act as a platform for free expression in parts of Europe where these values are strained.

Radio Free Europe and Russian station Radio Liberty, which it merged with, have been broadcasting to eastern Europe and Russia since 1950. While its remit originally was to fight communism, it now states its function as serving the cause of democracy more generally.

Today in Chechnya, for example, RFE is the only station where you will hear reports from journalists and stringers in the Chechen language about the influence of Isis and the persecution of gay people. It is the only Western international station operating in Moldova, even if it broadcasts for only a few hours a day. In Armenia, its TV provides a counterbalance to government-controlled media, as well as broadcasting to the wider diaspora. And in Kazakhstan, it provided special coverage of the early parliamentary election last year with six hours of live-streamed video on its website.

John O’Sullivan, executive editor of RFE between 2008 and 2012, argues passionately that “the radios”, as he calls the stations, have key roles to play in making sure people have a strong source of news and hear different viewpoints, and in holding governments to account with local journalists reporting on the ground.

“At the moment, there is a moral war between all these countries and the argument that commercial stations can do this job is fine, except they can’t do the job of the radios,” he told Index. “CNN is … never going to have a lot of correspondents in Armenia and never going to have correspondents in Chechnya. It’s going to be doing a story once every three months. Those audiences need it every day.”

Originally set up as an intelligence services-led project, RFE aimed to counter what the US government saw as superior propaganda coming out of the Soviet Union. Although primarily funded by the CIA, it was promoted to the US public as a project for truth and freedom to which they should contribute. Future US president Ronald Reagan, a young actor in the early 1950s, fronted up the public service advertisement, encouraging donations with the exhortation: “This station daily pierces the Iron Curtain with the truth, answering the lies of the Kremlin and bringing a message of hope to millions trapped behind the Iron Curtain.”

Victoria Phillips, who runs the RFE research project at Columbia University, told Index: “These men [who founded RFE] … really did believe in the power of truth and freedom of ideas, and when I read about some of those people, you don’t like the fact that they tried to invade places, and they had coups, but in the end the core was a belief in the power of ideas, and if ideas are allowed to vent then good will take place…”[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”2/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”RFE was accused of encouraging insurgents to believe the USA would intervene on their behalf militarily” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]In the beginning, the broadcasts used émigrés and dissidents for their programmes. They spoke from the headquarters in Munich to their countrymen and women in their own languages and were broadcast on short wave radios, which were widely accessible. It was an alternative source of news to the official Soviet broadcasters.

During the Cold War RFE was also a hotbed of spies, double agents and political resistance. The Bulgarian novelist and playwright Georgi Markov was assassinated in London with the tip of a poisoned umbrella in part because of his RFE In Absentia programme. Markov had dined with the communist elite and knew all about their lives. He revelled in satirising them and the absurdity of the system for his audience back home. According to the communist government he “insolently mocked” the regime and “encouraged dissidence”.

When O’Sullivan was executive director RFE/RL, he remembers the Iranian secret service taking pictures of the Iranian journalists coming into the offices, then in Prague, in an effort to intimidate them. “We know in a general way that some of the countries had agents embedded in the service which broadcast to them. We didn’t know who they were obviously. And in one particular case, in the Russian service, [there was] a man who had defected [back to Russia]. He had been in RFE during the Cold War and he defected and went to work for Radio Moscow and he subsequently wrote a tell-all memoir in which he had to confess that journalistic standards in Radio Moscow were well below the standards in Radio Free Europe, or in his case Radio Liberty.”

Later, RFE played an instrumental role in the fall of the USSR. As writer Irena Maryniak explained in an article for Index in 2010: “Western radios became a forum for dissenting views and personalities: people like Václav Havel (later president of the Czech Republic); the Russian physicist and civil rights activist Andrei Sakharov; the Polish historian Adam Michnik; or indeed maverick party members like Boris Yeltsin, who broadcast on Radio Liberty when he was out of favour with colleagues at home.”

Today, many of the 23 countries where RFE works are areas where the USA still wants foreign policy influence. It broadcasts across a huge range of media, not just radio. And the languages and countries the station covers, from the Caucasus and the Balkans to Afghanistan via Iran and Pakistan, read like a map of East-West tension.

Indeed, the congressionally funded Broadcasting Board of Governors, which has openly funded RFE since the 1970s and pours $117 million of taxpayers’ money into the service, is robust about its “soft power” intentions. Its 2016 budget report contains headings such as Countering a Revanchist Russia. And the report explicitly links broadcasting with foreign policy priorities.

So can we trust its journalism? The answer from O’Sullivan is yes. It’s not constrained to put the US view in the same way as Voice of America, and it actively seeks to encourage free speech and news coverage in countries where this is underdeveloped or difficult. Indeed, many reporters risk their lives to report for RFE, such as Khadija Ismayilova, who was imprisoned in Azerbaijan for exposing the president’s link to corruption. She was awarded the Unesco/Guillermo Cano World Press Freedom Prize in 2016 for her fearless work for the station. The station also won two prizes at the New York Festivals’ International Awards this spring, including one for the Kyrgyz service’s short video feature A Snowy Trek on Horseback to Teach School.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”2/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”The people who were broadcasting suddenly realised that there were huge ramifications if you promised, or seemed to promise, something and it didn’t come true.” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]There have been darker moments at RFE, the most famous being its reporting on the Hungarian uprising of 1956 when at least 2,500 people were killed and many more were forced into exile, imprisoned and deported. RFE was accused of encouraging insurgents to believe the USA would intervene on their behalf militarily and therefore making people risk their lives unnecessarily. A couple of its programmes offered tactical military advice, and one commentary told people not to give up their weapons.

George Urban, the director of the Radio Free Europe division at the time, admitted they got it wrong. He said: “The radio was young and inexperienced. After barely five years of broadcasting, its management was still testing the instruments and boundary lines of the Cold War and was simply not up to the task of responding with clarity or finesse to its first great challenge. Hungary, its baptism of fire, cost it dear.”

As Phillips said: “The people who were broadcasting suddenly realised that there were huge ramifications if you promised, or seemed to promise, something and it didn’t come true. That people were going to die; your friends were going to die.”

Despite these controversies, RFE has survived, in part because the US Congress has continued to invest in the European operation, if on a smaller scale than during the Cold War. But O’Sullivan believes “the radios” should be given a lot more money and are needed more than ever to compete with stations like Russia Today (with a budget of about $300 million in 2016) and Al Jazeera.

“I think that people will accept there is an argument for good journalism which gives the news about their own country to people whose country would like to deprive them of it, and good journalism which sets standards to which we hope the journalists in transitioning countries will aspire and gradually achieve,” he said.

This article was updated on 1 November 2017 to include additional information.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]This article first appeared in the Autumn 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine, an award-winning, quarterly magazine dedicated to fighting for free expression and against censorship across the globe since 1972. You can subscribe here or via Exact Editions here. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”89160″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0306422011399691″][vc_custom_heading text=”Surviving Lukashenko ” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422011399691|||”][vc_column_text]March 2011

James Kirchick looks at the climate for alternative media in the aftermath of the 2010 Belarus elections.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”94267″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228208533431″][vc_custom_heading text=”Extolling the communist party” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228208533431|||”][vc_column_text]October 1982

Janis Sapiets questions whether Soviet broadcasting is partaking in censorship or responsibility to the party. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”94034″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228308533503″][vc_custom_heading text=”Censorship in retreat” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228308533503|||”][vc_column_text]April 1983

Hungary’s best-known novelist writes on the craving in Eastern Europe for communication and exchanges of ideas.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Free to air” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:%20https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F09%2Ffree-to-air%2F|||”][vc_column_text]Through a range of in-depth reporting, interviews and illustrations, the autumn 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores how radio has been reborn and is innovating ways to deliver news in war zones, developing countries and online

With: Ismail Einashe, Peter Bazalgette, Wana Udobang[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”95458″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/09/free-to-air/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Each week, Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project verifies threats, violations and limitations faced by the media throughout the European Union and neighbouring countries. Here are five recent reports that give us cause for concern.

The Russian state media regulator Roskomnadzor began blocking Krym Realii, the Сrimean edition of Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty on Saturday 14 May.

A representative of Roskomnadzor confirmed that the regulator had blocked a page, which contains an interview with a leader of the Tatar Mejlis, at the request of the general prosecutor office. “Currently, Roskomnadzor is implementing measures for blocking and closing this website,” criminal prosecutor Natalia Poklonskaya told Interfax.

Krym Realii was established following the annexation of Crimea to Russia. Materials on the site are published in Russian, Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar languages.

Several editors at RBC media holding lost their jobs on 13 May following a meeting between top management with journalists. They include RBC editor-in-chief Elizaveta Osetinskaya, editor-in-chief of the RBC business newspaper Maksim Solyus, and RBC deputy chief editor Roman Badanin.

In a press release, RBC underlined that the dismissals were finalised as a mutual agreement of both parties, but sources from TV-Dozhd and Reuters claim managers have bowed to political pressure from the Kremlin.

The pressure against RBC began following investigations that have reportedly “irked the Kremlin“, including one on the assets of Vladimir Putin’s alleged daughter, Ekaterina Tikhonova.

#Croatia demands perpetrators be found after RTL TV journalist Petar Panjkota attacked at #Bosnia Serb protest pic.twitter.com/qCPVWVv5L0

— Balkan Newsbeat (@BalkanNewsbeat) May 15, 2016

Petar Panjkota, a journalist for the Croatian commercial national broadcaster RTL, was physically assaulted after he had finished a segment from the Bosnian town Banja Luka on 14 May.

Panjkota was reporting on parallel rallies in Banja Luka, the administrative centre of Bosnia’s Serb-dominated of Republika Srpska. He was reporting on protests organised by the ruling and opposition parties of the Bosnian Serbs. When he went off air, Panjkota was punched in the head by an unidentified individual, leaving bruises.

RTL strongly condemned the attack, calling it another attack on media freedom. No information has surfaced on the identity of the assailant.

On 12 May, the long-awaited white paper on the future of the BBC was unveiled. The BBC Trust is to be abolished and replaced by a new governing board including ministerial appointees. The board will be comprised of 12 to 14 members: the chair, deputy chair and members for each of the four nations of the UK will be appointed by the government and the remaining seats will be appointed by the BBC.

“It is vital that this appointments process is clear, transparent and free from government interference to ensure that the body governing the BBC does not become simply a mouthpiece for the government,” Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index on Censorship, said.

“Independence from government is essential for the BBC and these proposals don’t quite offer that,” Richard Sambrook, director of the Centre for Journalism at Cardiff School of Journalism, Media and Cultural Studies and former BBC journalist, told Index on Censorship. “There is no reason the board can’t be appointed by an arms length, independent panel. Currently the plans are too close to a state broadcasting model.”

Reporter of Kurdish news agency DIHA Sermin Soydan was arrested today becoming agency’s 13th imprisoned journalist pic.twitter.com/qhEC1BSbjg

— Mutlu Civiroglu (@mutludc) May 15, 2016

Two reporters working for Dicle News Agency (DİHA) reporters were detained in the eastern city of Van on 12 May. Nedim Türfent and Şermin Soydan were allegedly detained within the scope of an on-going investigation and taken to the anti-terror branch in the central Edremit district of Van.

Both were detained separately. According to Bestanews website, Nedim Türfent was detained when his car was stopped by state forces at the entrance of Van. Şermin Soydan was detained on her way to cover news in the city of Van.

Mapping Media Freedom

|

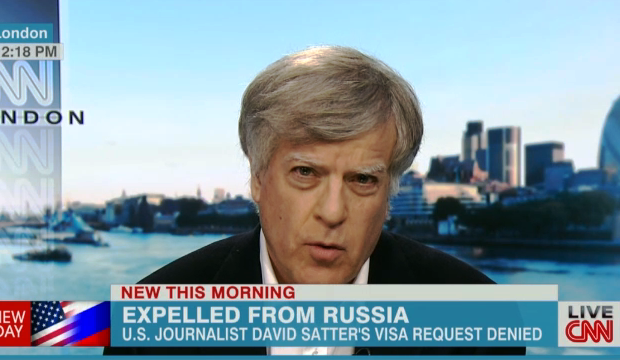

Fielding calls in the back of a London black cab, American journalist David Satter is a busy man.

Satter, who has reported on Soviet and Russian affairs for nearly four decades, was appointed an adviser to US government-funded Radio Liberty in May 2013. In September, he moved to Moscow. But at Christmas, he was informed he was no longer welcome in the country — the first time this has happened to an American reporter since the cold war.

Since Monday night, when the news of his expulsion from Russia broke, he’s been talking pretty much non stop, attempting to explain the manoeuvres which led to him being exiled from his Moscow home.

A statement issued by the Russian foreign ministry claims that Satter had violated Russian law by entering the country on 21 November, but not applying for a visa until 26 November.

Satter dismisses this as “nonsense”, saying he had been assured that a visa that had expired on 21 November would be renewed the following day, with no gap. As it happened, the visa was not renewed on time, “in order to create a pretext”, he tells Index.

To cut a short cut through a labyrinthine tale of bureaucracy: Satter says he left Russia in order to gain a new entry visa, which he could then exchange for a residency visa as an accredited correspondent for Radio Liberty.

He was repeatedly told this visa had been secured. Eventually, on 25 December, he was told that he had a number for a visa, but not the necessary invitation to accompany it. “Kafkaesque”, he calls it. The embassy official had never heard of this happening before. And, as Satter points out, he would not have been issued a number for a new visa in December if it had not been approved.

Eventually, he was told to speak to an official named as Alexei Gruby, who told him that “the competent organs” (code, Satter says, for the FSB) had decided that his presence in Russia was not desirable, language normally reserved for spies. “And now we see I have been barred for five years.”

“The point is, I urge you not to get caught up in their bureaucratic intrigues…the real reason was given to me, in Kiev, on 25 December.”

Is this just another example of FSB muscle flexing?

“Possibly. I’ve known them for a number of years, and I can’t always understand what they’re doing. Usually what they do is not very good…”

This is not Satter’s first brush with the Russian secret services. In a long career with the Financial Times, Radio Liberty and other outlets, he has experience of the KGB and its sucessor. “In 1979, they tried to expel me, accusing me of hooliganism. They once organised a provocation in one of the Baltic republics in which they posed as dissidents. I spent a couple of days with them, thinking I was with dissidents – I was really with the KGB. It’s a long history. It’s in my movie. We showed it in the Maidan [December’s anti-government protests in Ukraine]. Maybe they didn’t like that.”

Satter’s film, the Age of Delirium, is an account of the fall of the Soviet Union.

Is this expulsion a personal thing? Or a move against Radio Liberty? “It’s hard to say whether it’s me, or Radio Liberty, or both.”

Satter is concerned at leaving behind research materials and belongings in Moscow, saying it is likely his son, a London-based journalist, will have to go to Russia to collect them “unless they reverse their decision, which I hope they do”.

In spite of the recent amnesty that saw Pussy Riot’s Nadezhda Tolokonnikova and Maria Alyokhina released from prison, as well as opposition figure Mikhail Khodorkovsky, the diagnosis for free speech in Russia is not good. Alyokhina dismissed her release as a “hoax”, designed to prove Putin’s power. Meanwhile, state broadcaster RIA Novosti has been dissolved and reimagined as “Rossia Segodnya” (“Russia Today” – no coincidence it bears the same name as the notorious English language propaganda station), with many fearing closer Kremlin control.

One Russian journalist I spoke to felt that, ahead of the Sochi games, the expulsion of Satter is a message to all journalists: no matter how experienced, well-known, and well-supported you are, you are still at the mercy of the authorities.

This article was posted on 14 Jan 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

Last week was a painful one for free speech in Russia.

Tens of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty Moscow bureau journalists were fired within two days. First an entire internet department, then radio hosts, reporters and producers — around 90 per cent of RFE/RL’s Moscow staff became jobless.

A further 5 per cent quit in protest, including me.

RFE/RL broadcasts on medium waves will end on 10 November due to amendments to the law on mass media which state a radio cannot broadcast in a primary service area if more than 5 per cent of it is owned by foreign individual or legal entity. RFE/RL’s broadcasts in Russia will only be available online through its website.

In a in a statement released on 24 September, the service’s American manager Steve Korn stressed changes were made to improve RFE/RL’s Russian service. Yet in a letter to the US Congress Committee on Foreign Relations, notable Russian human rights activists wrote: “The KGB couldn’t have done worse for Radio Liberty’s image, as well as the image of USA in Russia, than American managers Julia Ragona and Steve Korn have done”. In a letter, the activists added:

Professionals with irreproachable reputation were fired; while a newly appointed RFE/RL’s Russian Service director [Masha Gessen] is a person whose managing skills were receiving negative assessments on her previous positions.

They asked the Congress to create a commission for a thorough investigation into Radio Liberty’s managers’ activities, which they said “harmed the USA’s public image in Russia”, and requested they “revise the decisions”.

Gessen, who will oficially take her post of RFE/RL Russian Service director on 1 October, denies allegations of “cleaning up the media for her new team”.

Korn and Ragona have not commented on the issue.

The switch to online and departure from medium waves will occur without the people who, over past few years, made Radio Svoboda (as it is known in Russian) the second most quoted radio station after Echo Moscow (which has an FM frequency), according to data from monitoring service Medialogia. Radio Liberty’s website was very much original. Decoded programmes’ texts formed just a small part of website content. It consisted mainly of informative pieces, blogs and a large multimedia section with video reports, documentaries and live video broadcasts.

The internet team, which I had the honour to be a part of, increased the number of visitors and the core audience tenfold. Radio Svoboda achievements were hailed by Broadcasting Board of Governors.

However, the mass dismissals were made.

RFE/RL was established in the 1950s in the United States as a private non-profit mass media organisation funded by the American Congress through the Broadcasting Board of Governors (BBG). RFE/RL broadcasts in 21 countries and 28 languages. Russian service history began soon after Stalin died in March 1953, but until 1988 its broadcasts were jammed as “anti-Soviet”. It was the “enemy’s voice” during the Cold War.

In August 1991, after RFE/RL’s full coverage of the August Coup, president Boris Yeltsin issued a decree allowing Radio Liberty to broadcast in Russia. The document was given personally to former RFE/EL journalist Mikhail Sokolov, who was fired last week together with the overwhelming majority of his colleagues.

Since Yeltsin’s decree Radio Svoboda was retransmitted by Russian FM stations. This ended soon after Putin’s second presidential term began in 2006. The official reason concerned incorrect registration documents. However, most Radio Svoboda staff believed this was a form of censorship. The radio was forced to broadcast across short and medium waves, AM frequencies and online.

No law was violated in last week’s events, Radio Svoboda former staff say, but moral and ethical values were.

The amendments to the mass media law are not the only means of targeting groups that receive overseas funding. Since Vladimir Putin’s return to the presidency in May this year, a law has been passed which forces foreign-funded NGOs involved in political activity to register as “foreign agents” in Russia.

The tragicomic element is that the editorial office, which consisted of people fighting against censorship and advocating for freedom of expression, was destroyed not by its antagonists, but by its own chiefs at the expense of American taxpayers, whose money was used in the name of promoting democracy.