Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

It is important the international community pays close attention to the scale of politically motivated persecutions in Belarus, a panel discussion organised by the media organisation Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty recently said.

It was after Zmitser Dashkevich, a well-known Belarusian activist originally charged with extremism, had his sentence extended by a year after being charged with “blatantly disobeying penitentiary guards“. His sentenced was due to end in July. Journalist Andrei Aliaksandrau, a former employee of Index, recently spent his 1000th night behind bars after being imprisoned for 14 years in October 2022 for “extremist activities” against the state.

Anastasiia Kruope, assistant researcher for the Europe and Central Asia Division of Human Rights Watch, said there has been a large increase in human rights abuses and politically motivated persecutions in Belarus following Aleksandr Lukashenka’s heavily contested presidential election win in 2020.

“An atmosphere of fear and intimidation for journalists and human rights defenders was created,” she added.

“The way these people are treated in prisons and labelled extremist, along with the silencing of family members outside, means some of these cases may amount to crimes against humanity according to the UN.”

Aleh Hruzdzilovich was one such prisoner. A journalist for Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, he spent nine months in prison and was released in September 2022. After covering the protests following Lukaskenka’s re-election for his job, he was arrested and charged with actively taking part in them.

“From the very first day, people like me recorded as extremists are punished more and have a stigma in prison,” Hruzdzilovich explained.

“It means we’re put in punishment cells and solitary confinement more often. When I was tortured, I was told to sleep on the wooden floor. If I simply sat down or stopped walking around the cell in the daytime, I was reported and given more time in the punishment cell.”

Hruzdzilovich described seeing a prisoner wet himself through fear of being sent to a punishment cell.

Pavel Sapelko is a lawyer based at the Viasna Human Rights Centre in Minsk, Belarus. He said there is an absolute power of prison authorities over prisoners in Belarus, which is affecting their human rights, and seemingly makes people “disappear”.

“The prisoners are simply incommunicado. The authorities can shut down visits and calls from families, and even then can only get help from a lawyer after their sentences are passed by law.”

Speaking of the legal system in Belarus, Sapelko described the debilitating change that has occurred over the past three years.

“We’ve lost more than 300 defence lawyers, with 100 of them being disbarred. Licences have been revoked, and six defence lawyers are actually behind bars, now prison inmates themselves,” he explained.

“This massively affects a lawyer willing to take on your case, especially for those charged with being extremists.”

Ending with another reason why the international community should support those journalists and human rights defenders still in Belarus with things such as legal help and visas, Kruope had one eye on the future.

“They have the connections to document these abuses. The powerful tool we have is accountability, and it may take many years for abusers to face justice. We can focus on preserving the evidence against these abuses and document them for the future.”

Please read about Letters from Lukashenka’s Prisoners here, which is a collaborative project by Index on Censorship in partnership with Belarus Free Theatre, Human Rights House Foundation and Politzek.me.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

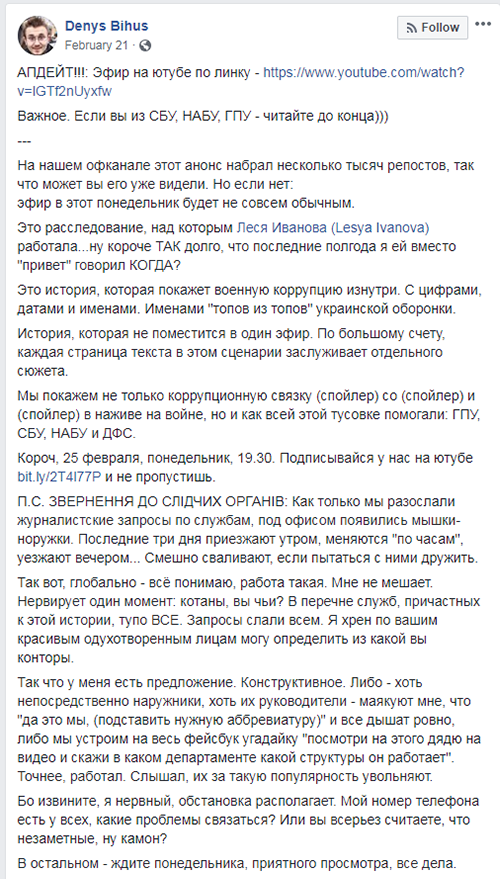

Bihus and members of his reporting team noticed several

unidentified people monitoring their activity from outside their Kiev office starting on February 20. Bihus wrote that the monitoring began after Bihus.Info sent requests for comment to law enforcement bodies in relation to an investigative article alleging corruption within Ukraine’s defense industry.

As Ukrainians head into the first round of a tense presidential election on 31 March, Ukraine’s incumbent president and candidate Petro Poroshenko is at the centre of a corruption scandal involving the military and the country’s press are feeling the heat.

The allegations swirling around the president were uncovered by the 2019 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award-nominated Bihus.info, a group of independent investigative journalists, who undertook a multi-year investigation. The Bihus.info revelations were central to the president’s decision to fire Oleh Hladkovskyy, a top national-security official, who was implicated in corrupt deals involving the armed forces.

Denys Bihus, editor-in-chief of Bihus.info, posted on his Facebook page that unknown persons had been surveilling members of his team ahead of the publication of the investigation. Bihus believes the surveillance was organised by Ukrainian law enforcement and was related to the outlet’s investigations into corruption involving the Prosecutor General’s Office, the Security Service of Ukraine, the National Anti-Corruption Bureau and the State Fiscal Service.

In February, journalists from the TV programme Schemes: Corruption in Details, another leading investigative journalistic project jointly run by public broadcaster UA:Pershyi and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, reported being followed and surveilled. Ukrainian oligarch Rinat Akhmetov has been accused of hiring personnel to spy on journalist Mykhailo Tkach and the camera crew of Schemes. The journalists claimed these activities have been aimed at obstructing their work.

Akhmetov’s security firm has accused Schemes journalists of breaching the oligarch’s privacy and collecting information illegally. The company said that over the past few months unknown persons had secretly filmed the office of SCM, a company owned by Akhmetov, more than 200 times, as well as the private homes of a shareholder. The company claims that those persons had not identified themselves as media workers.

However, Tkach said that Akhmetov’s security firm knew that he and his crew were journalists as they had shown their press cards. Police initially questioned Tkach in late February after he filed a complaint about the firm’s obstruction of journalistic activity. At first, the investigators intended to interrogate him as a witness, but Tkach insisted that he should be defined as an aggrieved party. According to Ukrainian laws, an aggrieved party has more rights in a proceeding: to see material about the case, to file complaints and statements.

In another alarming trend, Ukrainian prosecutors demanded access to the electronic correspondence of the investigative journalist Ivan Verstyuk who collaborated with the Novoye Vremya weekly magazine. On 4 February a court in Kiev allowed law enforcement to gain access to the journalist’s emails.

In 2016 Novoye Vremya published an article by Verstyuk about Olexander Korniyets, a deputy prosecutor of the Kiev region, who paid for his daughter Anastasia’s expensive study in London. According to the UK National Crime Agency report, Korniyets spent about £120,000, while the official annual income of the prosecutor and his wife did not exceed £8,000 per year.

This report, which was the basis of Verstyuk’s article, had been sent exclusively to the Ukrainian Prosecutor General’s Office, but was then leaked. Korniyets was fired in 2015, but Ukrainian prosecutors still haven’t finished investigating his case. They claim that Verstyuk’s story and his source breached the confidentiality of this investigation, despite the leaked report being readily available online.

Verstyuk is preparing a lawsuit for the European Court of Human Rights to protect himself from searches by the prosecutor general’s office.

The prosecutors’ efforts to obtain access to Verstyuk’s emails have drawn international condemnation. Harlem Desir, the representative on the freedom of the media at the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe, urged Ukrainian authorities to respect journalists’ right not to disclose their sources. The Committee to Protect Journalists also condemned the authorities’ efforts to get access to Verstyuk’s emails. Reporters Without Borders said that “it is becoming a habit to trample on the protection of journalistic sources in Ukraine. Head of the National Union of Journalists Serhiy Tomilenko commented that “It’s a shame! It’s an encroachment of media freedom”.

On 6 March journalist Kateryna Kaplyuk and a cameraman Borys Trotsenko from Schemes were assaulted by two deputies of the Chabany village head in the village of Chabany (Kiev region). The pair were filming on the premises of Chabany village council. The assailants were two deputies of the Chabany village head. The journalists called for an ambulance and, after a medical check-up at a hospital, Trotsenko was diagnosed with having a concussion. His camera was broken.

Nataliya Sedletska, editor-in-chief of Schemes, said the journalists had gone to Chabany village council to get information for an investigation on public lands illegal detachment into private possession. A complaint was filed to the police.

On 28 March Schemes reported that unidentified individuals had been trying to access the programme’s accounts in Telegram, WhatsApp and social media sites. On 7 February at 4:07 am, unknown Kyiv residents received access to Telegram account of Maxim Savchuk. In a few minutes at 4:15am, an attempt was made to access the Telegram account of journalist Valeriya Yegoshyna, who suggested that an attempt to break into her account could be connected to her investigation of social media bots acting in the interests of politicians Arseniy Yatsenyuk and Mykola Martynenko, from the ruling People’s Front party. In early March, unidentified persons tried to break the Facebook account of Schemes journalist Katerina Kapluk and accessed the WhatsApp account of editor Daria Martynenko.

Sedletska said the attempts to access the accounts are directly related to the professional activities of journalists.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”10″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1553851892349-06473364-7471-4″ taxonomies=”742, 8996″][/vc_column][/vc_row]