Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Tuesday’s ruling from the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) said that internet search engine operators must remove links to articles found to be outdated or irrelevant at the request of individuals. Index on Censorship’s CEO Jodie Ginsberg joined Max Mosley on Channel 4 News to debate why the ruling could lead to further censorship and the re-writing of history.

Tuesday’s ruling from the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) said that internet search engine operators must remove links to articles found to be outdated or irrelevant at the request of individuals.

No legal oversight, no legal framework, no checks and balances

Although it was made with intention of protecting European citizens’ personal data, the court’s ruling opens the door for anyone to request that anything be hidden from a search engine database with no legal oversight. The ruling could have negative implications to freedom of expression in the EU.

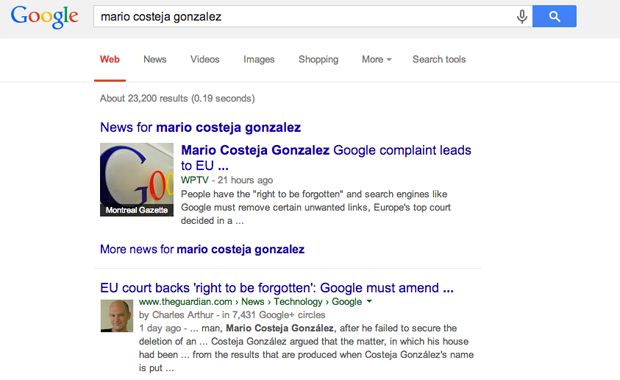

The case dates back to March 2012, when a Spanish citizen, Mario Costeja González, filed a complaint against Google and the newspaper La Vanguardia after discovering that a Google search for his name produced results referring to his homes repossession and auction for non-payment of social security contributions in 1998.

González argued that the 1998 auction notice mentioned in La Vanguardia should no longer be linked to his name in internet searches.

The information on La Vanguardia site had been published legally and was protected by the right to information. However, relying upon the EU’s data protection directive — which the CJEU last year argued did not establish a right to be forgotten, the judges ruled that González’s privacy rights override not only the economic interest of Google as a search engine, but also “the interest of the general public in having access to that information upon a search relating to [González’s] name.” As a result they ordered all links to the auction notice be removed from Googles search results.

The ruling now makes it possible for individuals to request an internet search engine operator to remove links to content found outdated or irrelevant following a search made on the basis of a person’s name. The request can be about any item, included lawful pages, containing true information, that are publicly available. While it’s understandable that people might want to restrict access to private information (embarrassing pictures, for example), Index does not believe that the ruling addresses this in an appropriate way.

A search engine is not a publisher and it neither owns nor stores the web pages containing information relating to a person, especially when this information emanates from public records. The courts ruling sets different standards between search engines, which are intermediaries, and publishers, who produce the content and are responsible for making the information public. In this particular case, it will mean there is a difference between searching what is publicly available in the newspaper archives in a local library and what is publicly available on the internet.

Privatisation of censorship: allowing search engines to become censor-in-chief

The US magazine The Atlantic notes the court ruling explicitly mentions González’s auction notice. So would that mean the ruling itself could be made unsearchable online if Gonzalez requested it? It would be up to Google and others discretion to decide whether or not the public’s right to access the court decision overrides González’s privacy.

The ruling specifies that a fair balance should be sought between the public’s right to access given information and the data subjects right to privacy and data protection, but one of our greatest concerns is that it does not provide any legal framework for the search engine operator to implement the removal, nor does it provide sufficient elements to guarantee public interest defence against removal. It leaves to private companies the power to amend search results without any legal oversight and checks and balances.

The ruling makes a search engine operator a controller able to rectify, erase or block links to information publicly available. According to the judges, the controller must take every reasonable step to ensure that data which do not meet the requirements of that provision are erased or rectified. It means that private companies such as Google or Yahoo would be in a position to decide whether or not information is “adequate, relevant” and “kept up to date”. There is a provision in the ruling for public interest to be taken into account but, again, this is not something that search engines should be deciding. Furthermore, the ruling does not provide for what happens when irrelevant information is hidden from public view and then becomes suddenly relevant because a former nobody suddenly becomes, say, a public figure.

Alongside practical implications for companies that would be required to implement the ruling, search engine operators should not be responsible for taking such decisions. Should they choose to refer decisions to local information commissioners, the commissioners could find themselves deluged with requests they simply do not have the resources to manage. Britain’s Information Commissioner has already described the regime as one no one will pay for.

A bad precedent for countries within and outside Europe

Although the ruling was welcomed by some as a clear victory for the protection of personal data of Europeans; it clearly restricts EU citizens right to information freely available on the internet. The ruling as it stands could be used to censor legitimate content and takes Europe closer to countries that have a tradition of internet control. At a time when the number of takedown requests is increasing globally, and more countries are banning Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, Index fears this ruling could further empower those who try to silence information available on the web and rein in online freedom of expression.

Journalists who live in countries where they experience censorship everyday understand this instantly; this is about removing information at whim from the public domain or at least making it much harder to find. Making it more difficult for journalists to undercover stories about fraud, child abuse and expenses scandals. And just because an individual would rather that information could not be found.

In Turkey for example, the government blocked the country’s access to YouTube in March, after banning Twitter earlier in the month, in an effort to quell anti-government sentiment prior to local elections. The government officially banned Twitter after the network refused to take down an account accusing a former minister of corruption. In the Turkish case, there is the risk that material objectionable to the government would be more easily removed by deleting the links to relevant articles and blog posts.

“This is worrying news because the right to be forgotten can quickly morph into the right to polish ones public image, using privacy rights as an excuse. The public also has rights, and access to public information about citizens is one of those,” says Turkish journalist Kaya Genc. “In the age of social media, it is very difficult to tell who is a public figure our lives are all public now and the sooner we accept this, the better.”

In the end, the ruling leaves more questions than it answers: Who decides what’s “relevant”? Which person gets to hide access to which information? What stories will be made to “disappear”? When does a story become out of date? Could US citizens search for information about EU citizens on search engines that EU citizens would not be able to see?

And how long before this article is inaccessible because someone mentioned in it wants to hide it from public view?

This article was posted on May 14, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

Today’s decision from the Court of Justice of the European Union violates the fundamental principles of freedom of expression.

The court’s ruling means that, under certain circumstances, information can be removed from search engine results even if it is true and factual and without the original source material being altered. It allows individuals to complain to search engines about information they do not like with no legal oversight. This is akin to marching into a library and forcing it to pulp books. Although the ruling is intended for private individuals it opens the door to anyone who wants to whitewash their personal history.

By placing the onus on search engines to prevent dissemination of information, the Court has said that an individual’s desires outweigh society’s interest in the complete facts around incidents.

The ruling goes against the finding last year of the EU advocate general who said there was no “right to be forgotten”.

The Court’s decision is a retrograde move that misunderstands the role and responsibility of search engines and the wider internet. It should send chills down the spine of everyone in the European Union who believes in the crucial importance of free expression and freedom of information.

Interview requests can be directed to + 44 (0)207 260 2660.

In light of the recently passed Californian law allowing minors to delete any of their online activity, Index organised a Google Hangout in association with student newspapers York Vision and The Student Journals, on whether young people should have the right to be forgotten on social media.

Watch the discussion between York Vision editor Patrick Greenfield, Student Journals editor Amy Ashenden and Index’ Alice Kirkland and Milana Knezevic below.

What do you think? Have your say in the comments or tweet us at @IndexCensorship.