Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

By international comparison, Putin’s ‘win’ in the recent elections in Russia was practically marginal.

Forget the ruthless despots of yesteryear; Putin’s victory could put him in the running for the title of “Worst Dictator Ever” securing as he did, just 87% of the vote and struggling to convince a whole 13% of Russia’s population that he deserves their vote.

Putin’s efforts to reach the dizzying heights of previous autocratic excellence is not without precedent.

Nicolae Ceaușescu, the Romanian maestro of self-delusion, once claimed a staggering 98.8% approval rating from voters who seemingly found his continued leadership irresistible.

And, of course, the multiple successes of Saddam Hussein, who, not content with anything less than perfection, treated himself to not one, but two elections where he waltzed away with a cool 99% of the vote, leaving the remaining 1% presumably too busy planning their escape routes to bother casting a ballot.

Even by recent standards, Putin’s election efforts fall into the ‘must try harder’ category. Take Paul Kagame – head of state in the unquestionably safe state of Rwanda – secured an impressive 98.8% of the vote in 2017. By coincidence, his two challengers were deemed not to have met the nomination threshold by the Rwandan Electoral Commission.

And even by Russian standards, Putin is an under-achiever. The absolutely above board and beyond reproach referendum in 2014 that took place in Crimea saw the Ukranian peninsula experience a collective outbreak of Russiophilia, with a jaw-dropping 96.77% of voters deciding that annexation was their number one wish.

But of course, when it comes to precarious polls, poor Putin is but an enthusiastic amateur of electoral absurdity when compared to North Korea’s Kim Jong Un whose 2019 flawless victory saw him win 100% of the vote. Imagine that, Putin. A leader so popular that no-one felt the need to vote against you.

So, at Index on Censorship, we offer our commiserations to Putin on an election which will inevitably cause him to struggle to look his fellow dictators in the eye. But he should take heart, for in the grand tapestry of dictatorial hubris, he may have fallen short of the coveted triple-digit approval rating, but he’s certainly earned his place in the hall of shame. Bravo!

But in all seriousness, dictators yearn for legitimacy but equally cannot resist inflating their egos with absurd election results. Putin’s 87% victory is merely the latest in a long line of autocrats entangled in their own delusions. For them, the allure of unchecked power is intoxicating, and the illusion of overwhelming support is irresistible. So they manipulate, coerce, and fabricate, all in the name of bolstering their image and maintaining their iron grip on power.

Yet, in their desperate pursuit of approval, they only reveal the hollow emptiness of their rule and the farcical nature of their so-called “elections.”

In the grand theatre of autocracy, where dictators vie for the title of “Most Absurd Electoral Farce,” Vladimir Putin may have inadvertently claimed the crown as the reigning champion of underachievement.

His inability to secure a unanimous victory serves as a glaring reminder of the limitations of his power and the resilience of those who dare to defy his iron grip.

While we chuckle at his inflated ego and his desperate grasp for legitimacy, let us not forget the sobering reality faced by millions of Russians who lack the freedom to express dissent without fear of reprisal.

We can poke fun at Putin’s absurdity but we must also reaffirm our commitment to democracy and freedom of expression, values that remain elusive for too many in Putin’s Russia.

And we stand with the 13%.

A major new global ranking index tracking the state of free expression published today (Wednesday, 25 January) by Index on Censorship sees the UK ranked as only “partially open” in every key area measured.

In the overall rankings, the UK fell below countries including Australia, Israel, Costa Rica, Chile, Jamaica and Japan. European neighbours such as Austria, Belgium, France, Germany and Denmark also all rank higher than the UK.

The Index Index, developed by Index on Censorship and experts in machine learning and journalism at Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU), uses innovative machine learning techniques to map the free expression landscape across the globe, giving a country-by-country view of the state of free expression across academic, digital and media/press freedoms.

Key findings include:

The countries with the highest ranking (“open”) on the overall Index are clustered around western Europe and Australasia – Australia, Austria, Belgium, Costa Rica, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Sweden and Switzerland.

The UK and USA join countries such as Botswana, Czechia, Greece, Moldova, Panama, Romania, South Africa and Tunisia ranked as “partially open”.

The poorest performing countries across all metrics, ranked as “closed”, are Bahrain, Belarus, Burma/Myanmar, China, Cuba, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Eswatini, Laos, Nicaragua, North Korea, Saudi Arabia, South Sudan, Syria, Turkmenistan, United Arab Emirates and Yemen.

Countries such as China, Russia, Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates performed poorly in the Index Index but are embedded in key international mechanisms including G20 and the UN Security Council.

Ruth Anderson, Index on Censorship CEO, said:

“The launch of the new Index Index is a landmark moment in how we track freedom of expression in key areas across the world. Index on Censorship and the team at Liverpool John Moores University have developed a rankings system that provides a unique insight into the freedom of expression landscape in every country for which data is available.

“The findings of the pilot project are illuminating, surprising and concerning in equal measure. The United Kingdom ranking may well raise some eyebrows, though is not entirely unexpected. Index on Censorship’s recent work on issues as diverse as Chinese Communist Party influence in the art world through to the chilling effect of the UK Government’s Online Safety Bill all point to backward steps for a country that has long viewed itself as a bastion of freedom of expression.

“On a global scale, the Index Index shines a light once again on those countries such as China, Russia, Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates with considerable influence on international bodies and mechanisms – but with barely any protections for freedom of expression across the digital, academic and media spheres.”

Nik Williams, Index on Censorship policy and campaigns officer, said:

“With global threats to free expression growing, developing an accurate country-by-country view of threats to academic, digital and media freedom is the first necessary step towards identifying what needs to change. With gaps in current data sets, it is hoped that future ‘Index Index’ rankings will have further country-level data that can be verified and shared with partners and policy-makers.

“As the ‘Index Index’ grows and develops beyond this pilot year, it will not only map threats to free expression but also where we need to focus our efforts to ensure that academics, artists, writers, journalists, campaigners and civil society do not suffer in silence.”

Steve Harrison, LJMU senior lecturer in journalism, said:

“Journalists need credible and authoritative sources of information to counter the glut of dis-information and downright untruths which we’re being bombarded with these days. The Index Index is one such source, and LJMU is proud to have played our part in developing it.

“We hope it becomes a useful tool for journalists investigating censorship, as well as a learning resource for students. Journalism has been defined as providing information someone, somewhere wants suppressed – the Index Index goes some way to living up to that definition.”

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Governments are using the Covid-19 crisis to change freedom of information laws and, unless we are very careful, important stories could get unreported. Since the beginning of the crisis, governments from Brazil to Scotland have made changes to their FOI laws; some of the changes are rooted in pragmatism at this unprecedented time; others may be inspired by more sinister motives.

FOI laws are a vital part of the toolkit of the free media and form a strong pillar that supports the functioning of open societies.

According to a 2019 report by Unesco – published some two and a half centuries after the first such law was introduced in Sweden – 126 countries around the world now have freedom of information laws. These typically allow journalists and the general public the right to request information relating to decisions made by public bodies and insight into administration of those public bodies.

US president Thomas Jefferson once wrote: “Whenever the people are well informed, they can be trusted with their own government; that whenever things get so far wrong as to attract their notice, they may be relied on to set them to rights.”

Now in this time of crisis, freedom of information processes are being shut down, denied unless they relate specifically to the crisis or the deadlines for responses are being extended.

When the Covid-19 crisis first erupted, we made a decision to monitor attacks on media freedom. It wasn’t just a random idea; we know that in similar times of crisis, repressive governments often attack the work that journalists do – sometimes the journalists themselves – or introduce new legislation they have wanted to do for some time and now see a time of crisis as an opportunity to do so without proper scrutiny.

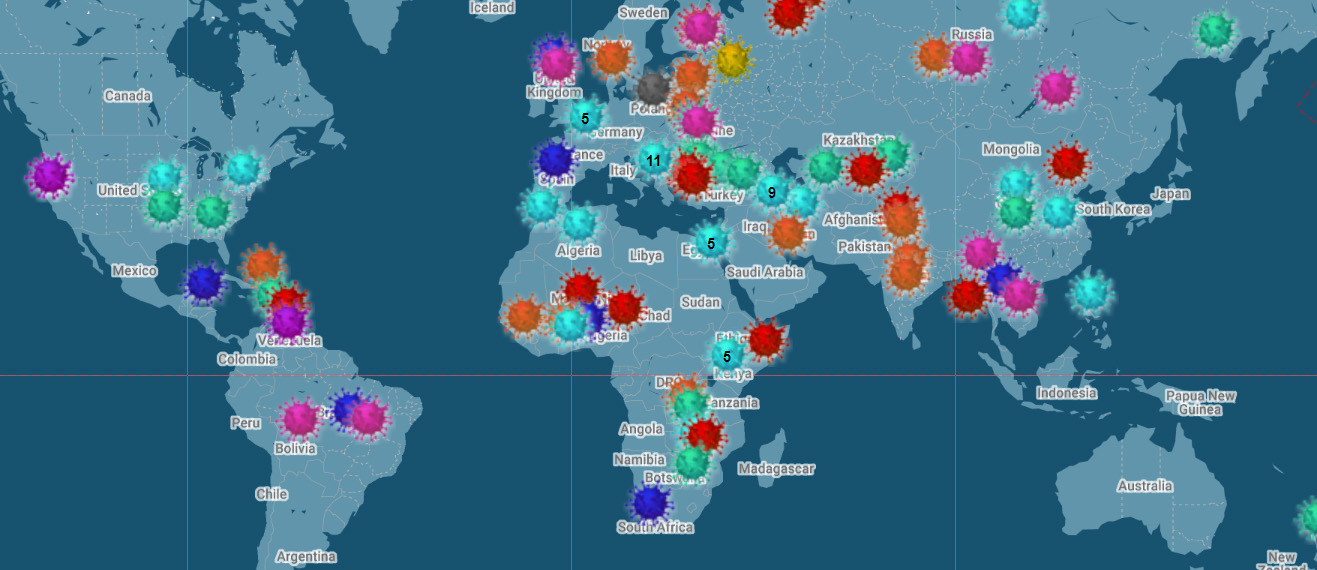

Since the start of the crisis, we have been collecting reports on attacks on media freedom through an innovative, interactive map. More than 125 incidents have been reported by our readers, our network of international correspondents, our staff in the UK and our partners at the Justice for Journalists Foundation. Many relate to changes to FOI legislation.

Let us be clear there can be legitimate reasons for amending legislation in times of international crisis. With many public officials forced to work from home, many do not have access to the information they need or the colleagues they need to consult to be able to answer journalists’ requests. Others need more time to be able to put together an informed response.

Yet both restrictions and delays are worrying. They allow politicians and public bodies to sweep information that should be freely available and subject to wider scrutiny under the carpet of coronavirus. News that is three months old is, very often, no longer news.

In its Coronavirus (Scotland) Bill, the Scottish government has agreed temporary changes to the Freedom of Information (Scotland) Act 2002 that extend the deadlines for getting response to information requests from 20 to 60 working days. The initial draft wording sought to allow some agencies to extend this deadline by a further 40 days “where an authority was not able to respond to a request due to the volume and complexity of the information request or the overall number of requests being dealt with by the authority”. However, this was removed during the reading of the bill following concerns raised by the Scottish information commissioner.

The bill was passed unanimously on 1 April and became law on 6 April. As it stands the new regulations remain in force until 30 September 2020 but can be extended twice by a further six months.

In Brazil, President Jair Bolsonaro has issued a provisional measure which means that the government no longer has to answer freedom of information requests within the usual deadline. Marcelo Träsel of the Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalism says the measure is “dangerous” as it gives scope for discretion in responding to requests.

The decree compelled 70 organisations to sign a statement requesting the government not to make the requested changes, saying “we will only win the pandemic with transparency”.

Romania and El Salvador are among the other countries which have stopped FOI requests or extended deadlines. By contrast, countries such as New Zealand have reocgnised the importance of FOI even in a crisis. The NZ minister of justice Andrew Little tweeted: “The Official Information Act remains important for holding power to account during this extraordinary time.”

FOI law changes are not the only trends we have noticed.

Index’s deputy editor Jemimah Steinfeld has noted how world leaders are ducking questions on coronavirus while editorial assistant Orna Herr has written about how the crisis is providing pretext for Indian prime minister Narendra Modi to increase attacks on the press and Muslims.

If you are a journalist facing unreasonable delays in receiving information from public bodies at this time, do report it to us at bit.ly/reportcorona.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Each week, Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project verifies threats, violations and limitations faced by the media throughout the European Union and neighbouring countries. Here are five recent reports that give us cause for concern.

5 August, 2016 – Twelve journalists were arrested on terror charges following a court order, independent press agency Bianet reported.

According to Bianet: “The court on duty has ruled to arrest Alaattin Güner, Şeref Yılmaz, Ahmet Metin Sekizkardeş, Faruk Akkan, Mehmet Özdemir, Fevzi Yazıcı, Zafer Özsoy, Cuma Kaya and Hakan Taşdelen on charges of “being a member of an armed terrorist organisation” and Mümtazer Türköne, columnist of the now closed Zaman Daily on charges of “serving the purposes of FETÖ (Fethullahist Terrorist Organisation)” and Hüseyin Turan and Murat Avcıoğlu on charges of “aiding a [terrorist] organization as non-member”.

Warrants for the detainment of all 13 Zaman newspaper journalists were issued on 27 July 2016 by Turkish authorities.

Also read: 200 Turkish journalists blacklisted from parliament

4 August, 2016 – Monica Gubernat, a member and chairperson of the National Audiovisual Council of Romania, cut off the live transmission of a council debate, news agency Mediafax reported.

An ordinance says that all meetings of the council must be broadcasted live on its website.

The institution has recently purchased equipment to broadcast debates, which was set to go live on 4 August, 2016. A member of the council, Valentin Jucan, even issued a press statement about the live broadcast.

The chairperson, Monica Gubernat was opposed to it, saying that she was not informed about the broadcast, and asked for a written notification about the transmission.

ActiveWatch and the Centre for Independent Journalism announced they would inform the supervisory bodies of the National Audiovisual Council of Romania and the culture committees of the Parliament about the “abusive behavior of a member of the council” and asked for increased transparency within this institution.

The National Audiovisual Council of Romania is the only regulator of the audiovisual sector in Romania. Their job is to ensure that Romania’s TV channels and radio stations operate in an environment of free speech, responsibility and competitiveness. In practice, the council’s activity is often criticised for its lack of transparency and their politicised rulings.

2 August, 2016 – British blogger Graham Phillips and freelance journalist Billy Six, forcibly entered the offices of non-profit investigative journalism outlet Correctiv, filmed without permission and accused staff of spreading lies, the outlet reported on its Facebook page on Wednesday 3 August.

According to Correctiv’s statement, Phillips had been seeking to confront Marcus Bensmann, the author of a Correctiv article which claimed that Russian officers had shot down the passenger airplane crossing over Ukraine in July 2014.

Phillips maintains the Ukrainian military is responsible for the crash.

2 August, 2016 – Police officers prevented freelance journalist Dzmitry Karenka from filming near the Central Election Commission office located in the Belarusian Government House in Minsk, the Belarusian Association of Journalists reported.

The journalist reported intended to film a video on the last day when candidates for the House of Representatives, Belarusian lower chamber, could register.

At 6am he was approached by police officers who told him that administrative buildings in Belarus can be filmed “only for the news” and asked him to show his press credentials which he didn’t have as he is a freelance journalist.

Karenka told the Belarusian Association of Journalists that he spoke with the police for over an hour before he was released and advised not to film administrative buildings.

Also read: Belarus: Government uses accreditation to silence independent press

1 August, 2016 – The website of the Dutch edition of Turkish newspaper Zaman Today was hit by a DDoS attack, broadcaster RTL Nieuws reported.

The website, known to be critical of the Erdogan government, was offline for about an hour.

An Erdogan supporter reportedly announced an attack on the website earlier via Facebook. Zaman Today said it will be pressing charges against him.

Also read: Turkey’s media crackdown has reached the Netherlands

Mapping Media Freedom

|