Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

The Autumn issue of Index magazine focuses on the struggle for environmental justice by indigenous campaigners. Anticipating the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26), in Glasgow, in November, we’ve chosen to give voice to people who are constantly ignored in these discussions.

Writer Emily Brown talks to Yvonne Weldon, the first aboriginal mayoral candidate for Sydney, who is determined to fight for a green economy. Kaya Genç investigates the conspiracy theories and threats concerning green campaigners in Turkey, while Issa Sikiti da Silva reveals the openly hostile conditions that environmental activists have been through in Uganda.

Going to South America, Beth Pitts interviews two indigenous activists in Ecuador on declining populations and which methods they’ve been adopting to save their culture against the global giants extracting their resources.

Cover of Index on Censorship Autumn 2021 (50-3)[/caption]

Cover of Index on Censorship Autumn 2021 (50-3)[/caption]

A climate of fear, by Martin Bright: Climate change is an era-defining issue. We must be able to speak out about it.

The Index: Free expression around the world today: the inspiring voices, the people who have been imprisoned and the trends, legislation and technology which are causing concern.

Pile-ons and censorship, by Maya Forstater: Maya Forstater was at the heart of an employment tribunal with significant ramifications. Read her response the Index’s last issue which discussed her case.

The West is frightened of confronting the bully, by John Sweeney: Meet Bill Browder. The political activist and financier most hated by Putin and the Kremlin.

An impossible choice, by Ruchi Kumar: The rapid advance of Taliban forces in Afghanistan has left little to no hope for journalists.

Words under fire, by Rachael Jolley: When oppressive regimes target free speech, libraries are usually top of their lists.

Letters from Lukashenka’s prisoners, by Maria Kalesnikava, Volha Takarchuk, Aliaksandr Vasilevich and Maxim Znak: Standing up to Europe’s last dictator lands you in jail. Read the heartbreaking testimony of the detained activists.

Bad blood, by Kelly Duda: How did an Arkansas blood scandal have reverberations around the world?

Welcome to hell, by Benjamin Lynch: Yangon’s Insein prison is where Myanmar’s dissidents are locked up. One photojournalist tells us of his time there.

Cartoon, by Ben Jennings: Are balanced debates really balanced? Ask Satan.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Special Report” font_container=”tag:h2|font_size:22|text_align:left”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Credit: Xinhua/Alamy Live News

It’s not easy being green, by Kaya Genç: The Turkish government is fighting environmental protests with conspiracy theories.

It’s in our nature to fight, by Beth Pitts: The indigenous people of Ecuador are fighting for their future.

Respect for tradition, by Emily Brown: Australia has a history of “selective listening” when it comes to First Nations voices. But Aboriginal campaigners stand ready to share traditional knowledge.

The write way to fight, by Liz Jensen: Extinction Rebellion’s literary wing show that words remain our primary tool for protests.

Change in the pipeline? By Bridget Byrne: Indigenous American’s water is at risk. People are responding.

The rape of Uganda, by Issa Sikiti da Silva: Uganda’s natural resources continue to be plundered.Cigar smoke and mirrors, by James Bloodworth: Cuba’s propaganda must not blight our perception of it.

Denialism is not protected speech, by Oz Katerji: Should challenging facts be protected speech?

Permissible weapons, by Peter Hitchens: Peter Hitchens responds to Nerma Jelacic on her claims for disinformation in Syria.

No winners in Israel’s Ice Cream War, by Jo-Ann Mort: Is the boycott against Israel achieving anything?

Better out than in? By Mark Glanville: Can the ancient Euripides play The Bacchae explain hooliganism on the terraces?

Russia’s Greatest Export: Hostility to the free press, by Mikhail Khordokovsky: A billionaire exile tells us how Russia leads the way in the tactics employed to silence journalists.

Remembering Peter R de Vries, by Frederike Geeerdink: Read about the Dutch journalist gunned down for doing his job.

A right royal minefield, by John Lloyd: Whenever one of the Royal Family are interviewed, it seems to cause more problems.

A bulletin of frustration, by Ruth Smeeth: Climate change affects us all and we must fight for the voices being silenced by it. Credit: Gregory Maassen/Alamy[/caption]

Credit: Gregory Maassen/Alamy[/caption]

The man who blew up America, by David Grundy: Poet, playwright, activist and critic Amiri Baraka remains a controversial figure seven years after his death.

Suffering in silence, by Benjamin Lynch and Dr Parwana Fayyaz The award-winning poetry that reminds us of the values of free thought and how crucial it is for Afghan women.

Heart and Sole, by Mark Frary and Katja Oskamp: A fascinating extract gives us an insight into the bland lives of some of those who did not welcome the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Secret Agenda, by Martin Bright: Reforms to the UK’s Official Secret Act could create a chilling effect for journalists reporting on information in the public interest.

Index’s new issue of the magazine looks at the importance of whistleblowers in upholding our democracies.

Featured are stories such as the case of Reality Winner, written by her sister Brittany. Despite being released from prison, the former intelligence analyst is still unable to speak out after she revealed documents that showed attempted Russian interference in US elections.

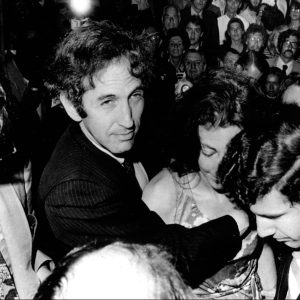

Playwright Tom Stoppard speaks to Sarah Sands about his life and new play title ‘Leopoldstatd’ and, 50 years on from the Pentagon Papers, the “original whistleblower” Daniel Ellsberg speaks to Index .

Daniels Ellsberg is a former US Government contractor who worked for Rand Corporation and exposed the country’s long-term involvement in Vietnam through the release of the Pentagon Papers in 1971.

Nerma Jelacic works for the Commission for International Justice and Accountability, which gathers war crimes evidence during ongoing conflicts.

Sir Tom Stoppard is a Czech-born British playwright and screenwriter who’s written for radio, stage and television.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

A Russian fan at the Euro 2020 match between Belgium and Russia. Stanislav Krasilnikov/Tass/PA Images

In celebration of one of football’s biggest international tournaments, here is Index’s guide to the free speech Euros. Who comes out on top as the nation with the worst record on free speech?

It’s simple, the worst is ranked first.

We continue today with Group B, which plays the deciding matches of the group stages today.

Unlike their relatively miserable performances on the football pitch, Russia can approach this particular contest as the clear favourites.

The group would be locked up after the first two games, with some sensational play from their three talismans: disinformation, oppressive legislation and attacks on independent media.

Russian disinformation, through the use of social media bots and troll factories, is well known, as is their persistent meddling in foreign elections which infringes on the rights of many to exercise their right to vote based on clear information.

Putin’s Russia has increased its attacks on free speech ever since the 2011 protests over a flawed election process. When protests arose once again all over the country in January 2021 over the detention of former opposition leader Alexei Navalny, over 10,000 people were arrested across the country, with many protests violently dispersed.

Police in the country must first be warned before a protest takes place. A single-person picket is the only form of protest that does not have this requirement. Nevertheless, 388 people were detained in Russia for this very act in the first half of 2020 alone, despite not needing to notify the authorities that eventually arrested them.

Human rights organisation, the Council of Europe (COE), expressed its concerns over Russian authorities’ reactions to the Navalny protests.

Commissioner Dunja Mijatović said: “This disregard for human rights, democracy and the rule of law is unfortunately not a new phenomenon in a country where human rights defenders, journalists and civil society are regularly harassed, including through highly questionable judicial decisions.”

Unfortunately, journalists attempting to monitor these appalling free speech violations face a squeeze on their platforms. Independent media is being deliberately targeted. Popular news site Meduza, for example, is under threat from Russia’s ‘foreign agents’ law.

The law, which free expression non-profit Reporters Without Borders describes as “nonsensical and incomprehensible”, means that organisations with dissenting opinions receiving donations from abroad are deemed to be “foreign agents”.

Those who do not register as foreign agents can receive up to five years’ imprisonment.

Being added to the register causes advertisers to drop out, meaning that revenue for the news sites drops dramatically. Meduza were forces to cut staff salaries by between 30 to 50 per cent.

Belgium is relatively successful in combating attacks on free speech. It does, however, make such attacks arguably more of a shock to the system than it may do elsewhere.

The coronavirus pandemic was, of course, a trying time for governments everywhere. But troubling times do not give leaders a mandate to ignore public scrutiny and questioning from journalists.

Alexandre Penasse, editor of news site Kairos, was banned from press conferences after being accused by the prime minister of provocation, while cartoonist Stephen Degryse received online threats after a cartoon that showed the Chinese flag with biohazard symbols instead of stars.

Incidents tend to be spaced apart, but notable. In 2020, journalist Jérémy Audouard was arrested when filming a Black Lives Matter protest. According to the Council of Europe “The policeman tried several times to prevent the journalist, who was showing his press card, from filming the violent arrest of a protester lying on the ground by six policemen.”

There is an interesting debate around holocaust denial, however and it is perhaps the issue most indicative of Belgium's stance on free speech.

Holocaust denial, abhorrent as it may be, is protected speech in most countries with freedom of expression. It is at least accepted as a view that people are entitled to, however ridiculous and harmful such views are.

The law means that anyone who chooses to "deny, play down, justify or approve of the genocide committed by the German National Socialist regime during the Second World War" can be imprisoned or fined.

Belgium has also considered laws that would make similar denials of genocides, such as the Rwandan and Armenian genocides respectively, but was unable to pursue this due to the protestations of some in the Belgian senate and Turkish communities. It could be argued that in some areas, it is hard to establish what constitutes as 'denial', therefore, choosing to ban such views is problematic and could set an unwelcome precedent for future law making regarding free speech.

Comparable legal propositions have reared over the years. In 2012, fines were introduced for using offensive language. Then mayor Freddy Thielemans was quoted as saying “Any form of insult is from now on [is] punishable, whether it be racist, homophobic or otherwise".

Denmark has one of the best records on free speech in the world and it is protected in the constitution. It makes a strong case to be the lowest ranked team in the tournament in terms of free speech violations. It is perhaps unfortunate then, that they were drawn in a group with their fellow Scandinavians.

Nevertheless, no country’s record on free speech is perfect and there have been some concerning cases in the country over the last few years.

2013 saw a contentious bill approved by the Danish Parliament “reduced the availability of documents prepared”, according to freedominfo.org. Essentially, it was argued that this was a restriction of freedom of information requests which are vital tool for journalists seeking to garner correct and useful information.

Acts against freedom of speech tend to be individual acts, rather than a persistent agenda.

Impartial media is vital to upholding democratic values in a state. But, in 2018, public service broadcaster DR was subjected to a funding cut of 20 per cent by the right-wing coalition government.

DR were forced to cut around 400 jobs, according to the European Federation of Journalists, an act that was described as “revenge” at the time.

There have been improvements elsewhere. In 2017, Denmark scrapped its 337-year-old blasphemy law, which previously forbade public insults of religion. At the time, it was the only Scandinavian country to have such a law. According to The Guardian, MP Bruno Jerup said at the time: “Religion should not dictate what is allowed and what is forbidden to say publicly”.

The change to the law was controversial: a Danish man who filmed himself burning the Quran in 2015 would have faced a blasphemy trial before the law was scrapped.

In 2020, Danish illustrator Niels Bo Bojesen was working for daily newspaper Jyllands-Posten and replaced the stars of the Chinese flag with symbols of the coronavirus.

Jyllands-Posten refused to issue the apology the Chinese embassy demanded.

The Council of Europe has reported no new violations of media freedom in 2021.

A good record across the board, Finland is internationally recognised as a country that upholds democracy well.

Index exists on the principle that censorship can and will exist anywhere there are voices to be heard, but it wouldn’t be too crass of us to say that the world would be slightly easier to peer through our fingers at if its record on key rights and civil liberties were a little more like Finland’s.

It is joint top with Norway and Sweden of non-profit Freedom House’s Global Freedom Index of 2021, third in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index 2020, sixth in The Economist’s Democracy Index 2020 and second in RSF’s World Press Freedom Index.

Add that together and you have a country with good free speech protections.

That is not to say, though, that when cases of free speech violations do arise, they can be very serious indeed.

In 2019, the Committee to Project Journalists (CPJ) called for Finnish authorities to drop charges against journalist Johanna Vehkoo.

Vehkoo described Oulou City Councilor Junes Lokka as a “Nazi clown” in a private Facebook group.

A statement by the CPJ said: “Junes Lokka should stop trying to intimidate Johanna Vehkoo, and Finnish authorities should drop these charges rather than enable a politician’s campaign of harassment against a journalist.”

“Finland should scrap its criminal defamation laws; they have no place in a democracy.”

Indeed, Finnish defamation laws are considered too harsh, as a study by Ville Manninen on the subject of media pluralism in Europe, found.

“Risks stem from the persistent criminalization of defamation and the potential of relatively harsh punishment. According to law, (aggravated) defamation is punishable by up to two years imprisonment, which is considered an excessive deterrent. Severe punishments, however, are used extremely rare, and aggravated defamation is usually punished by fines or parole.”

The study also spoke of another problem, that of increased harassment or threats towards journalists.

Reporter Laura Halminen had her home searched without a warrant after co-authoring an article concerning confidential intelligence.

Group F[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title="You may also like to read" category_id="8996"][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image="116887" img_size="large"][vc_column_text]Why abusive legal threats and actions against journalists must be stopped.

Journalists are public watchdogs: by bringing information that is in the public interest to light, they help to hold power to account. But what if powerful or wealthy people wanted to keep their wrongdoings a secret? Abusive legal threats and actions, known as strategic lawsuits against public participation – or SLAPPs, are increasingly being used to intimidate journalists into silence. They are used to cover up unethical and criminal activity and to prevent the public of their right to know. SLAPPs have a devastating impact, not only on media freedom, but on human rights, rule of law, and our very democracies. This webinar hosted by Index on Censorship, the European Centre for Press and Media Freedom (ECPMF) and Foreign Policy Centre (FPC), will examine the issue of SLAPP and why we need to take action in the UK and the EU to stop them.

Speakers:

Bill Browder, Head of Global Magnitsky Justice Campaign (chair)

Annelie Östlund, financial journalist

Herman Grech, Editor in Chief of Times of Malta

Justin Borg Barthet, Senior Lecturer at University of Aberdeen

With contributions from:

Jessica Ní Mhainín, Policy and Campaigns Manager at Index on Censorship

Paulina Milewska, Anti-SLAPP Project Researcher at ECPMF

Susan Coughtrie, Project Director at Foreign Policy Centre

Register for tickets here.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text][/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]