17 Dec 2018 | Magazine, News, Volume 47.04 Winter 2018

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Vital moments during our lifetimes are complicated by taboos about what we can and can’t talk about, and we end up making the wrong decisions just because we don’t get the full picture, says Rachael Jolley in the winter 2018 issue of Index on Censorship magazine” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_column_text]

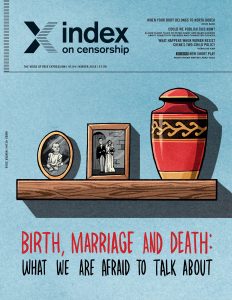

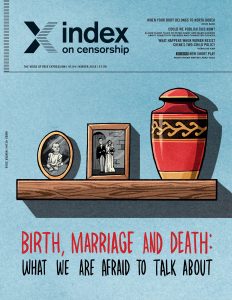

Birth, Marriage and Death, the winter 2018 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Birth, marriage and death–these are key staging posts. And that’s one reason why this issue looks at how taboos around these subjects have a critical impact on our world.

Sadly, there are still many of us who feel we can’t talk about problems openly at these times. Societal pressure to conform can be a powerful element in this and can help to create stultifying silences that frighten us into not being able to speak.

Being unable to discuss something that has a major and often complex impact on you or your family can lead to ignorance, fear and terrible decisions.

Not knowing about information or medical advice can also mean exposing people to illness and even death.

The Australian Museum sees death as the last taboo, but it also traces where those ideas have come from and how we are sometimes more shy to talk about subjects now than we were in the past.

The Sydney-based museum’s research considers how different cultures have disposed of the dead throughout history and where the concepts of cemeteries and burials have come from.

For instance, in Ancient Rome, only those of very high status were buried within the city walls, while the Ancient Greeks buried their dead within their homes.

The word “cemetery” derives from the Greek and Roman words for “sleeping chamber”, according to the Australian Museum, which suggests that although cremation was used by the Romans, it fell out of favour in western Europe for many centuries, partly because those of the Christian faith felt that setting fire to a body might interfere with chances of an afterlife.

Taboos about death continue to restrict speech (and actions) all around the world. In a six-part series on Chinese attitudes to death, the online magazine Sixth Tone revealed how, in China, people will pay extra not to have the number “4” in their mobile telephone number because the word sounds like the Mandarin word for “death”.

It also explores why Chinese families don’t talk about death and funerals, or even write wills.

In Britain, research by the charity Macmillan Cancer Support found just over a third of the people they surveyed had thoughts or feelings about death that they hadn’t shared with anyone. Fears about death concerned 84% of respondents, and one in seven people surveyed opted out of answering the questions about death.

These taboos, especially around death and illness, can stop people asking for help or finding support in times of crisis.

Mental health campaigner Alastair Campbell wrote in our winter 2015 issue that when he was growing up, no one ever spoke about cancer or admitted to having it.

It felt like it would bring shame to any family that admitted having it, he remembered. Campbell said that he felt times had moved on and that in Britain, where he lives, there was more openness about cancer these days, although people still struggle to talk about mental health.

Hospice director Elise Hoadley tells one of our writers, Tracey Bagshaw, for her article on the rise of death cafes (p14), that British people used to be better at talking about death because they saw it up close and personal. For instance, during the Victorian period it would be far more typical to have an open coffin in a home, where family or friends could visit the dead person before a funeral. And vicar Laura Baker says of 2018: “When someone dies we are all at sea. We don’t know what to do.”

In a powerful piece for this issue (p8), Moscow-based journalist Daria Litvinova reports on a campaigning movement in Russia to expose obstetric abuse, with hundreds of women’s stories being published. One obstacle to get these stories out is that Russian women are not expected to talk about the troubles they encounter during childbirth. As one interviewee tells Litvinova: “And generally, giving birth, just like anything else related to women’s physiology, is a taboo subject.” Russian maternity hospitals remain institutions where women often feel isolated, and some do not even allow relatives to visit. “We either talk about the beauty of a woman’s body or don’t talk about it at all,” said one Russian.

Elsewhere, Asian-American women talk to US editor Jan Fox (p27) about why they are afraid to speak to their parents and families about anything to do with sex; how they don’t admit to having partners; and how they worry that the climate of fear will get worse with new legislation being introduced in the USA.

As we go to press, not only are there moves to introduce a “gag rule” – which would mean removing funding from clinics that either discuss or offer abortion – but in the state of Ohio, lawmakers are discussing House Bill 565, which would make abortions illegal even if pregnancies arise from rape or incest or which risk the life of the mother. These new laws are likely to make women more worried than before about talking to professionals about abortion or contraception.

Don’t miss our special investigation from Honduras, where the bodies of young people are being discovered on a regular basis but their killers are not being convicted. Index’s 2018 journalism fellow Wendy Funes reports on p24.

We also look at the taboos around birth and marriage in other parts of the world. Wana Udobang reports from Nigeria (p45), where obstetrician Abosede Lewu tells her how the stigma around Caesarean births still exists in Nigeria, and how some women try to pretend they don’t happen — even if they have had the operation themselves. “In our environment, having a C-section is still seen as a form of weakness due to the combination of religion and culture.”

Meanwhile, there’s a fascinating piece from China about how its new two-child policy means women are being pressurised to have more children, even if they don’t want them — a great irony when, only a decade ago, if women had a second child they had to pay.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” size=”xl” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”Taboos, especially around death and illness, can stop people asking for help or finding support in times of crisis” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

In other matters, I have just returned from the annual Eurozine conference of cultural journals, this year held in Vienna. It was interesting to hear about a study into the role of this specific type of publication. Research carried out by Stefan Baack, Tamara Witschge and Tamilla Ziyatdinova at the University of Groningen, in the Netherlands, is looking at what long-form cultural journalism does and what it achieves.

The research is continuing, but the first part of the research has shown that this style of magazine or journal stimulates creative communities of artists and authors, as well as creating debates and exchanges across different fields of knowledge. Witschge, presenting the research to the assembled editors, said these publications (often published quarterly) have developed a special niche that exists between the news media and academic publishing, allowing them to cover issues in more depth than other media, with elements of reflection.

She added that in some countries cultural journals were also compensating for the “shortcomings and limitations of other media genres”. Ziyatdinova also spoke of the myth of the “short attention span”.

At a time when editors and analysts continue to debate the future of periodicals in various forms, this study was heartening. It suggests that there still is an audience for what they describe as “cultural journals” such as ours – magazines that are produced on a regular, but not daily basis which aim to analyse as well as report what is going on around the world. Lionel Barber, the editor of the Financial Times newspaper, spoke of his vision of the media’s future at the James Cameron Memorial Lecture at London’s City University in November. As well as arguing that algorithms were not going to take over, he said he was convinced that print had a future. He said: “I still believe in the value and future of print: the smart, edited snapshot of the news, with intelligent analysis and authoritative commentary.”

His belief in magazines as an item that will continue to be in demand, if they offer something different from something readers have already consumed, was made clear: “Magazines, which also count as print – are they going to just disappear? No. Look at The Spectator, look at the sales of Private Eye.”

The vibrancy of the magazine world was also clear at this year’s British Society of Magazine Editors awards in London, with hundreds of titles represented. Jeremy Leslie, the owner of the wonderful Magculture shop in London (which stocks Index on Censorship) received a special award for his commitment to print. This innovative shop stocks only magazines, not books, and has carved out a niche for itself close to London’s City University. Well done to Jeremy. Index was also shortlisted for the specialist editor of the year award, so we are celebrating as well.

We hope you will continue to show your commitment to this particular magazine, in print or in our beautiful digital version, and think of buying gift subscriptions for your friends at this holiday time (check out https://shop.exacteditions.com/index-on-censorship for a digital subscription from anywhere in the world). We appreciate your support this year, and every year, and may you have a happy 2019.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Rachael Jolley is editor of Index on Censorship. She tweets @londoninsider. This article is part of the latest edition of Index on Censorship magazine, with its special report on Birth, Marriage and Death.

Index on Censorship’s winter 2018 issue is Birth, Marriage and Death, What are we afraid to talk about? We explore these taboos in the issue.

Look out for the new edition in bookshops, and don’t miss our Index on Censorship podcast, with special guests, on Soundcloud.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Birth, Marriage and Death” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2018%2F12%2Fbirth-marriage-death%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The winter 2018 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores taboos surrounding birth, marriage and death. What are we afraid to talk about?

With: Liwaa Yazji, Karoline Kan, Jieun Baek[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_single_image image=”104225″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/12/birth-marriage-death/”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

2 Nov 2018 | Mapping Media Freedom, Media Freedom, News, Ukraine

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”103553″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Before his death, Pavel Sheremet was one of Ukraine’s leading investigative journalists. He most notably investigated government corruption and border smuggling in his native Belarus, leading to his arrest in 1997 but winning him CPJ’s International Press Freedom Award in the process. He was detained, harassed and arrested because of his work.

Then, in 2016, he was assassinated. And Ukrainian authorities still have not uncovered who’s to blame.

Sheremet had just left his home in Kyiv, Ukriane the morning of July 20, on his way to Radio Vesti’s offices to host his morning show. He’d only driven a few hundred feet when the car exploded, and he was dead.

Ukraine’s prime minister, Volodymyr Groysman, called the news “terrible” on the day of Sheremet’s death, and other Ukrainian officials said they were dedicated to solving the murder. An investigation was launched. But, even two years later, no arrests have been made and no police leads have been made public. Any developments in the investigation have been kept quiet, and many journalists have taken the case into their own hands.

A documentary titled “Killing Pavel,” released in May 2017 by two investigative journalism organisations, highlighted the gaps of Ukraine’s official investigation, in addition to showing footage from security cameras outside Sheremet’s apartment building. They identified a former member of the SBU, Ukraine’s security agency, outside the building the night before Sheremet’s death. The SBU is one of the organisations tasked with investigating the murder.

The discovery obviously led to questions. Though the former SBU agent denied involvement in the murder, authorities have not stated why he was there that night.

Two months later, the CPJ published an investigative report into Sheremet’s death and found that Ukraine’s primary line of questioning was focused on Russian involvement, though the country has not given evidence of their interference.

Meanwhile, the police chief in charge of the investigation resigned due to obstruction by her superiors, and police and security service officials are pointing fingers at each other for destruction of video evidence.

In the same report, the CPJ said that 35 Ukrainian investigators were working on the case, along with three state prosecutors, and conducting 1,800 interviews and reviewing 150 terabytes of video footage. Yet no suspects have been identified, even with security camera footage showing two people planting the bomb under Sheremet’s car and a clear photograph of one of the assassins.

The CPJ said the possibility of Ukrainian involvement “casts doubt on the credibility of the official investigation,” and recommended the Ukrainian president invite an “independent international inquiry” to ensure accountability. Though the president said he would accept such an investigator, no action has been taken.

The failure by the Ukranian government to properly investigate Sheremet’s death and to quickly place the blame on Russia has not gone unnoticed. They have been criticised by a number of human rights organisations and advocacy groups, including Index.[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]Additional reporting by Gillian Trudeau[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”96085″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]Maltese investigative journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia was killed by a car bomb near her home in Bidniji, Malta. Caruana Galizia reported on high-profile corruption investigations and had been sued multiple times. She filed a police report 15 days before the attack saying she was receiving death threats. Two months after the murder, 10 people were detained in connection with Galizia’s death. Three are now awaiting trial and have entered not guilty pleas. The magistrate will decide whether to excuse the men or take them into prosecution in front of a judge and jury. In the meantime, The Daphne Project is dedicated to investigating Galizia’s death and carrying on her work.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”98320″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]Ján Kuciak, a Slovakian investigative journalist, and his fiance were shot dead in their home on 21 February 2018. Kuciak was reporting on tax fraud among businessmen connected to the country’s ruling party. He had previously filed a complaint against businessman Marian Kočner, who was allegedly connected with the bankruptcy of Real Štúdio KFA. A month after the murders, on 27 March, investigators examined the crime scene but found no evidence. On 27 September, police detained eight people connected to Kuciak’s murder. Among them were Tomáš S, Miroslav M and Alena Z. Alena Z is said to have worked as an Italian-Slovak interpreter for businessman Marian Kočner. A sum of €70,000 was paid for the contract killing of Kuciak, prosecutor general Jaromír Čižnár said, according to Slovak newspaper Sme. Sme quoted Čižnár who stated that it is still unclear who ordered the contract killing and would not confirm or deny if Marian Kočner is a lead suspect, but said further charges could be made in the case. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1541160123163-ad0ff09d-ff03-10″ taxonomies=”6564″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

27 Sep 2018 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News, Russia

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”102893″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]

A country with the largest territory in the world and a turbulent modern history, Russia is home to one of the most difficult media landscapes and censorship has been tightening its grip with new-found strength.

Free media was virtually non-existent during the decades of Soviet rule. It wasn’t until 1991 that Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev signed a decree allowing the first independent media outlets to emerge. This was also the year the Soviet Union ceased to be, and Russia was born in its stead. The constitution of Russia, adopted in 1993, guaranteed, among other rights and freedoms, the freedom of speech.

In 2018 it is still the same country with the same constitution, but the initial euphoria for freedom ended abruptly in 2003 after the shake-up of the television channel NTV. From its foundation in 1993 through the early 2000s, NTV was the largest private broadcaster in Russia and a stronghold of free speech, which didn’t suit Vladimir Putin, who first became president in 2000. Witty, free-spoken hosts openly criticised the government, reported on its failures and produced sharp political satire. The undermining of the channel began in 1999 with governmental lawsuits, and the final blow was dealt soon after the tragic events around Nord Ost, the three-day theatre siege in 2002, also known as the Dubrovka terror attack. Putin’s displeasure with NTV’s honest coverage and investigation into the death of 129 hostages, who inhaled an unidentified state-administered gas, resulted in the firing of the network’s CEO Boris Jordan. Soon after, the channel ceased to exist only to be reborn as a state-controlled media outlet with the same name.

Today, mass media in Russia is quite a different scene. The government sets the tone for many things, including the attitude towards journalists. Who are the good guys and who are the bad guys? Which news events should be covered in state media and which are too upsetting to show to the country?

State-owned and state-friendly TV channels like Channel 1 and Rossiya are known for meticulously filtering the inflow of news and dropping the themes and subjects that may throw shadow on the government. The few independent outlets left standing, like Ekho Moskvy, Novaya Gazeta and Dozhd TV, have to endure harassment from power structures and take part in legal battles against governmental institutions and businesses willing to censor them.

Recent additions to Russian legislation make it easier to prosecute media outlets for their reporting. Financial struggle is also real for many Russian media, which are being purchased and reshaped according to the tastes of the new owners, who often happen to have close ties to the Kremlin. That’s what happened to RBC newspaper and TV channel, among others.

Self-censorship is prevalent in newsrooms as well.

The number of threats and acts of violence against journalists has increased three-fold within the last two years, reported Natalia Kostenko, the head of the ONF Centre for Legal Support of Journalists, at a conference in March 2018. Kostenko cited restriction of access, verbal threats, physical violence, damage to personal belongings and lawsuits as the most common misdemeanours against media workers.

However, media freedom is not the only concern in today’s Russia. The political climate has changed drastically over the last few years: the country has seen a surge of nationalism, xenophobia and religious fervour, and the revival of Soviet methods of dealing with “thought criminals”. Under recently passed legislation, a person can be imprisoned for a social media like or repost if anyone considers it to be hateful or extremist. The economic stagnation and financial crisis, which began in 2014 as the result of sanctions against Russia’s actions in Crimea and Donbass, has been an important factor in all of this and contributed to a new wave of emigration, or “brain drain”, that has hit the country. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”102871″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Journalists are emigrating from the country for the same reasons as other groups. Some leave to pursue better career opportunities at foreign news outlets. Some follow their families or marry abroad. Some simply want a safer, more open environment for themselves and their children.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”102872″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Veteran TV host Tatiana Lazareva found herself unable to find any work on Russian television after she and her husband Mikhail Shatz took part in covering opposition leader Alexey Navalny‘s protests in 2012. This got them blacklisted on most Russian TV channels. “I don’t have a profession anymore,” Lazareva told Dozhd TV in an interview last year. “As I see it now, they wanted to take not only television away from us, but any chance to make money, wanted us, like, to crawl on our knees and beg.”

She moved to Spain, where she and her family had been spending their holidays for 15 years, to raise her youngest daughter. Lazareva continues her charity work in Russia and heads a motivational programme for people over 50, but the door to journalism in her country remains closed.

Lazareva’s example is not unique, and many young journalists now prefer to either start their careers abroad or change professions. For some journalists, leaving Russia is the only possible choice.

Vocal and straightforward, Karina Orlova had been a journalist at Ekho Moskvy radio for over a year when the attack on the French magazine Charlie Hebdo took place. A few days after the massacre, she hosted a show with Maxim Shevchenko, a right-wing journalist and then-member of the Russian Presidential Council on Human Rights. Orlova asked Shevchenko to comment on the threatening statement made by Chechen Republic leader Ramzan Kadyrov in response to exiled businessman Mikhail Khodorkovsky’s suggestion that every media outlet should republish Charlie Hebdo’s controversial Prophet Mohammed caricatures as an act of solidarity. Kadyrov called Khodorkovsky “the enemy of all Muslims” and his “personal enemy”, and said he hoped someone “would make the fugitive answer” for his words. Shevchenko kept defending Kadyrov’s point of view, while Orlova attempted to get Shevchenko to acknowledge the severity of the threats and report them to the council. For this, she too became a target. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”102873″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Orlova’s mother discovered that threats were being made under the journalist’s profile on a website for local journalists. Orlova then began receiving threats through her Facebook account. She could tell there was something different about these threats – they weren’t like the usual outbursts she encountered while on air. The men, residents of Chechnya and Ingushetia, didn’t try to hide their identity. They called Orlova “the enemy of Islam” and promised to kill her in many different ways. At the same time, Kadyrov directed threats to Ekho’s staff chief editor Alexey Venediktov.

In haste, Orlova packed her things and boarded a flight to the United States, which she believed to be the safest place for her. It took her some time to feel comfortable in the new environment and polish her English skills. She still contributes to Ekho, but her main job is with an American political magazine.

“Return to Russia? I can’t, I don’t want to and I won’t. Russia is a dangerous country where the raging of the power structures got even more out of hand in the last three years,” Orlova says. “There are no independent courts, the police only chases the “enemies of the state” and robs local businesses.”

Despite being away from Russia for three years, Orlova’s name hasn’t been forgotten. “In January 2018 director Nikita Mikhalkov filmed an episode of his TV show, Besogon (“Exorcist” in Russian), about me. He called me Goebbels and a fascist for an old article in which I suggested that Russia needed a lustration, and all people who worked in the Soviet system should be excluded from the government. Last time Besogon covered an Ekho journalist, Tanya Felgengauer was brutally attacked,” Orlova said.

Echo Moskvy’s Tatiana Felgengauer, a host and one of the editor-in-chief’s deputies, was stabbed several times in the neck in the station’s office. (Photo: Facebook)

Ekho host Tatiana Felgengauer was stabbed in the throat in October 2017 at the station’s headquarters. The attacker pepper-sprayed a guard and went for Felgengauer once he reached the office. He was deemed to be a paranoid schizophrenic and sentenced to compulsory medical treatment by the court.

Yulia Latynina (Twitter)

As one of the most noticeable and outspoken radio hosts in Moscow, Felgengauer was criticised by Russian state outlets more than once. Just a week before the attack she was called a “traitor of the motherland” on state television for attending a conference sponsored by foreign human rights organisations. She survived thanks to quick medical attention and has since fully recovered and returned to work. Nevertheless, it was a very close call.

Soon after the attack Ksenia Larina, another Ekho journalist, began receiving death threats. Not taking any chances, she promptly left the country for Europe.

Yulia Latynina hosted her own show at Ekho while also contributing to the newspaper Novaya Gazeta. The sharp-tongued novelist and journalist has been an object of criticism for many years, but the final straw for her came in September 2018 when her car was burned out right outside her country house, which had previously been sprayed with a dangerous military-grade chemical. Latynina now spends her time between different countries and has no plans to return to Russia.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_column_text]

No other Russian outlet has seen more of their journalists threatened, attacked and murdered over the years than Novaya Gazeta. One of the last bastions of Russian free press standing, the newsroom works under extreme pressure, carrying on in the same line of work as their fallen colleagues, who paid with their lives to get the truth out.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”102877″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]2000, Igor Domnikov, reported on business corruption in Moscow. Beaten to death outside his apartment by multiple men wielding hammers. Some of the murderers were arrested and sentenced in 2007, while the mastermind of the crime was let go.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”102880″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]2003, Yury Schekochikhin, investigative journalist. Died of a mysterious 16-day illness, possibly poison. Real cause of death never determined, independent investigation banned, case closed.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”85407″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]2006, Anna Politkovskaya, most famous for reporting about the Second Chechen War. First poisoned in 2004, recovered; then shot dead in her apartment building right on Vladimir Putin’s birthday. Murderers found and jailed, mastermind never found, investigation closed. Politkovskaya won an Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award for her courageous journalism.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”102879″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]2009, lawyer Stanislav Markelov and freelance reporter Anastasia Baburova. Both shot in the head on a Moscow side street in broad daylight. Both the killers and the mastermind found and jailed.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”102878″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]2009, Natalia Estemirova, human rights activist and journalist in Chechnya. Abducted near her home and found dead with bullet wounds in a woodland miles away. The killer was identified by the officials and allegedly killed in ambush. The newspaper staff is skeptical of this version, as the man’s DNA samples didn’t match the ones found on the crime scene.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

It would only be fair to say that Novaya Gazeta management knows pretty well when a threat is real. So instead of waiting for governmental protection, they take their own precautions. Here are just some of the recent stories of those who left the country before it was too late, related by the paper’s former chief editor Dmitry Muratov:

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”102890″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]Sergey Zolovkin used to be a police officer who solved many crimes, co-founded Sochi newspaper and was a Novaya Gazeta author. He was threatened many times, his car sabotaged, relatives beaten up, an attempt on his life made in 2002 – the would-be killer was caught on the spot as Zolovkin was armed; he moved to Germany soon after.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”102891″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]Maynat Abdulaeva (Kurbanova) was reporting from Grozny, Chechnya, for years, until she and her family started receiving death threats. She has been living in Germany under PEN program Writers in Exile since 2004.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”102889″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]Evgeniy Titov left in 2016. He reported on human rights violations in Krasnodar and corruption around Sochi 2014 Olympics, was threatened by the police and private individuals, and requested asylum in Lithuania.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”102888″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]Elena Milashina co-authored the 2017 world-famous investigation about hundreds of gay men kidnapped, tortured and killed in Chechnya in a covert attempt to “purge” the region. Having been previously attacked and beaten up in 2006 and 2012, she fled Russia following death threats from Chechen officials and Muslim preachers, but continued to cover the region.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”102885″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]Ali Feruz (pen name) reported on hate crimes, LGBTQ and migrant worker’s rights. He was born in Uzbekistan, though his mother was Russian. He escaped from the country after being detained and tortured by the Uzbek National Security Service, who wanted his cooperation. Feruz moved to Russia and tried to obtain a Russian citizenship on jus sanguinis principle. His initial appeal was turned down, but a new case looked promising. He was suddenly arrested in August 2017 and sentenced to deportation to Uzbekistan. In the following three and a half months Feruz was abused and tortured in detention – and no one got punished for it. He was rescued and granted asylum by the German government, and will never be able to return to Russia. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”102886″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]Elena Kostychenko was one of Novaya Gazeta’s most fearless and fierce reporters, having covered complex stories all over Russia. She is also a feminist and LGBTQ activist, and in 2011 was left with a concussion after being attacked at a pride parade in Moscow. In 2016 Kostychenko was brutally beaten in Beslan while covering a protest of the mothers whose children died in the 2004 school terror attack. She is still recovering from psychological aftershocks, abroad.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

528 press freedom violations in Russia verified by Mapping Media Freedom as of 27/9/2018

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_raw_html]JTNDaWZyYW1lJTIwd2lkdGglM0QlMjI3MDAlMjIlMjBoZWlnaHQlM0QlMjIzMTUlMjIlMjBzcmMlM0QlMjJodHRwcyUzQSUyRiUyRm1hcHBpbmdtZWRpYWZyZWVkb20udXNoYWhpZGkuaW8lMkZzYXZlZHNlYXJjaGVzJTJGMTAwJTJGbWFwJTIyJTIwZnJhbWVib3JkZXIlM0QlMjIwJTIyJTIwYWxsb3dmdWxsc2NyZWVuJTNFJTNDJTJGaWZyYW1lJTNF[/vc_raw_html][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1538042702741-bc2cc3fd-837d-0″ taxonomies=”7349, 6564″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

20 Aug 2018 | Azerbaijan, Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News, Russia, Turkey, Ukraine

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_single_image image=”102216″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]Visitors to Eurasian countries — Turkey, Russia, Ukraine or, to a lesser extent, Azerbaijan — might be impressed by the sheer number of domestic television channels that offer news programming.

The average TV viewer in Turkey flipping through the local channels is treated to an alphabet soup — atv, Kanal D, NTV, STV, interspersed with FOX TV, CNN Türk, public broadcaster TRT and countless others — all employing a vast number of journalists and purporting to keep the viewers abreast of events shaping the domestic and global agenda. The broadcasts are slick: filled with chyrons, attention-grabbing graphics, remote reports, breaking news, heated exchanges between talking heads and all the other trappings of the modern-day 24-hour news cycle.

Watching the lively debates hosted by TV personalities, who exude an air of professionalism and discernment, with or without live audiences nodding in acquiescence or registering disapproval, viewers may be given the impression that they are being exposed to a wide range of opinions in a vibrant, competitive media market.

But does this wealth of channels translate into pluralism of points of view?

“Certainly not,” says Esra Arsan, journalism scholar and former columnist for Turkey’s Evrensel, one of the remaining newspapers supplying alternative news and commentary left in the country. “In Turkey, there’s no pluralistic media environment. The Turkish media have never been pluralistic in the true sense of the word, but at least there were once mechanisms that allowed for the voices of the right, left, mainstream and fringe wings to be heard, especially, on small media groups occupying the niche space,” she says, citing the formerly independent Turkish-language media, their Kurdish-language counterparts and those of other minority groups.

Arsan described the massive media reorganisation that took place in parallel with the rise of president Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s AKP party since 2007. “It was characterised by replacing the old media owners with the new ones with close ties to the government, and exercising total control over them, especially, in big media,” she adds.

During the Erdogan-inspired restructuring of the media, professional journalists and newsroom managers were forced out or jailed, Arsan says. The replacement managers left a lot to be desired. “Many of these people are uneducated, have no idea of journalistic ethics or professionalism, they’ve become the mouthpieces for the government”. She points out that more than 3,000 professional journalists who were working prior to 2007 are now jobless.

“Nowadays, no matter how many television broadcasters there are in Turkey, we can say the government exercises control over 90 percent of them,” says Ceren Sözeri, a communications faculty member at Istanbul’s Galatasaray University, citing a recent study conducted by Reporters Without Borders.

“Among the channels not under government control were stations belonging to Doğan Group, such as Kanal D and CNN Türk. Very recently, it was sold to Demirören Group, a conglomerate with close ties to the government,” Sözeri says.

Among the TV channels that are still able to provide diversity in the face of the pro-government news she tentatively cites FOX TV, Tele1 and HalkTV, the latter being associated with the CHP, the main opposition party. “With these exceptions, almost all other remaining channels work in conformity with the government, we can say we have an environment completely devoid of diversity,” Sözeri says.

Driven by Erdogan’s efforts to build a single-party regime, this media reorganisation pursued the goal of controlling information disseminated in the country. Buffered by the concurrent changes to the constitution and legal reforms, the jailing of journalists started to rise as well.

If this sounds familiar, that’s because it should: “What [Russian president] Putin did since he came to power, was establish control over influential media outlets that had the capacity to form public opinion, firstly, TV,” notes Gulnoza Said, Europe and Central Asia research associate at the Committee to Protect Journalists.

“All federal channels are very tightly controlled by the state now, with the instructions sent to the heads of TV companies on how to report on certain situations. It’s very clear that anybody who appears on your screen on a federal channel in Russia knows how they can and cannot speak about important and critical issues like Ukraine and Syria,” she says noting the two hot-button issues around Russia’s ongoing military involvement abroad.

According to the latest numbers released by the Media and Law Studies Association, a Turkish non-profit that offers legal protection to the rising number of journalists who find themselves in the crosshairs of the government, with 173 journalists in jail, Turkey currently holds the dubious title of the regional leader.

With 10 journalists currently in jail, according to a CPJ report, Azerbaijan is a distant second in the region, and number one among the former Soviet nations. Russia has five, according to the same report.

In addition to the state-owned AzTV and Ictimai (Public) TV that was created in 2005 as part of the country’s commitments before the Council of Europe, there are four nationwide broadcasters in Azerbaijan: Atv, Xazar, Space and Lider.

Azerbaijani media rights lawyer Alasgar Mammadli says that all these channels fail to inject diversity into the discourse in his country because no outlet presents a balanced viewpoint.

“The media only cover the government’s point of view. Considering the realities of Azerbaijan where the majority of information is obtained through TV and radio, we not only don’t have access to objective information, there’s no room for pluralistic news, we only have one expression, one colour.” He calls it “propaganda coming from the government that is disseminated to a large swath of the public,” noting that the internet is the only place offering some semblance of pluralism.

“In the entire region, I’d probably not name a single country where we’ve seen a positive trend, with the slight exception of, surprisingly, Uzbekistan,” says CPJ’s Said, noting that with the new administration of president Shavkat Mirziyoyev there has been a process of liberalisation, and for the first time in more than two decades, there are no journalists in jail.

Said notes that another negative trend is very visible in Ukraine since Russia annexed its region of Crimea in 2014. “At the time, after the Euromaidan [the wave of civil unrest that resulted in the government change], the Ukrainian media space had been relatively free for some time, but right now what we see is that the authorities are trying to control the flow of information, and the attempts are very visible and quite strong.”

Said explains that Ukrainian journalists are facing obstacles practically every day, stressing that she is not talking about Russian journalists trying cover the news from Ukraine. “The [Ukrainian] Ministry of Defense is making it extremely difficult for local journalists to get the so-called ‘military accreditation’ that would allow them to go to the eastern part of the country and cover combat operations,” says Said, adding that one of the newly imposed requirements is that the journalists applying for accreditation must provide previously written stories about the conflict.

“I would say it is censorship, because the government is trying to control the way the journalists cover the conflict,” she points out.

Galina Petrenko, director of Detector Media, a Ukrainian media watchdog organisation, disagrees: “There is pluralism [in Ukraine]. The economic interests doubtless manipulate the discourse, as the largest media belong not to the government, but to oligarchs, formidable businessmen conjoined with the power. That’s why business interests of each of these owners are reflected in the content of the media they own.”

Ukraine’s TV and radio council puts the number of the national TV broadcasters at 30, in addition to 72 regional channels. The country counts 120 satellite TV channels.

Maria Tomak of the Kyiv-based Media Initiative for Human Rights in Kyiv says that oligarchic ownership of the media has implications for pluralism. “We do have the freedom of speech, in comparison with Russia and other nations, but we do have limitations that are sometimes very tricky and are related to the economic factors, since we don’t have all that many independent media.”

She says that there is more than one “clan” or “group of influence” engaged in a struggle for power and influence. This conflict more or less preserves a tenuous pluralism. “When they start ‘oligarchic wars’, TVs show documentary footage or run news stories that clearly indicate who calls the shots at a particular channel. They mudsling or broadcast expose-style programmes, but it’s hard to call them objective, and it is hard to call it pluralism in its ideal sense.”

Bad examples are contagious

“The countries of the region quite often and quite speedily learn from each other’s negative experience,” says Mammadli. “For instance, Azerbaijan started officially blocking sites in February of 2017 through amendments to legislation. Before that, it was prevalent in Turkey and Russia.” He adds that the majority of the blocked sites are related to the alternative news sources. Mammadli puts the number of the internet sites and resources blocked in Russia at more than 136,000.

“We live in a region neighbouring Russia and Turkey and share ties with them, which speeds up the migration of these experiences into our country. Thus, the negative changes or attitudes towards human rights or the tendencies to limit freedom and rule of law in these countries can come to our country very fast,” he says. “It turns into a competition with the following logic, ‘the neighbor did it and got away with it, so let me try and see what happens’.’’

CPJ’s Said notes that these traditionally autocratic regimes keep one eye on the USA, which has been regarded as the flagman of press freedom and liberal democracy for decades. “Everybody used to look up at the USA, but since Trump was elected president, you know his routine, he wakes up in the middle of the night and starts tweeting, attacking journalists and critical media, calling everything they produce ‘fake news’.”

In her view, this definitely affects global press freedom, as dictators and elected officials with autocratic tendencies step up their pressure on critical media outlets in their own countries.

Arsan says of the effects of this phenomenon in Turkey: “If the dictator says the news is wrong or fake, even if you bring the most truthful news to them, be it on the issue of the human rights, war, the economy, the people will tend to disbelieve you. This makes the job of a journalist that much harder, because we chase the truth, and we see the tendency to disbelieve or outright denial on behalf of the audience.”

“Vulnerable stability” as the dangerous consequence

The shrinking plurality in the media throughout the entire region leads to a somewhat distorted processes of decision making during elections, says Said.

“The lack of plurality, which is a lack of democratic process or access to such, does, in general, make any society more vulnerable. If we look at the situation inside any country, also, when you look at dictators like Putin, you may get an impression that their power is very stable and strong. But that’s a very vulnerable stability,” she adds, explaining it with the fact that it is, ultimately, one person making decisions for the entire country of millions of people.

“If you look at what Erdogan has been doing for the last 10 years or so, he has been pursuing the policy of turning Turkey into a regional leader and suppressing any alternative voice. Same with Putin and his foreign policy in Ukraine with the annexation of Crimea, or Syria. In a way, it is back to the USSR, where people could discuss things only among their family or close friends in their kitchens.”

In the opinion of Arsan, as media plurality shrinks, societies become increasingly unaware of crises, which might set them on a path to disintegration. “This is the process of criminalising political discussion,” she said. “This is common in many Eurasian countries, as well as in the Middle East. These are the dictatorships without an end. People don’t want to go to the ballot boxes anymore because they don’t think they can effect change.”

For Mammadli, the people’s inability to access true information and analyse it means that they are contending with mass propaganda. From this point of view, the societies where people don’t know the truth will base their reactions on a lie, he says.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Media freedom is under threat worldwide. Journalists are threatened, jailed and even killed simply for doing their job.

Index on Censorship documents threats to media freedom in Europe through a monitoring project and campaigns against laws that stifle journalists’ work. We also publish an award-winning magazine featuring work by and about censored journalists.

Learn more about our work defending press freedom.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Index on Censorship’s project Mapping Media Freedom tracks limitations, threats and violations that affect media professionals in 43 countries as they do their job.

[/vc_column_text][vc_raw_html]JTNDaWZyYW1lJTIwd2lkdGglM0QlMjI3MDAlMjIlMjBoZWlnaHQlM0QlMjIzMTUlMjIlMjBzcmMlM0QlMjJodHRwcyUzQSUyRiUyRm1hcHBpbmdtZWRpYWZyZWVkb20udXNoYWhpZGkuaW8lMkZ2aWV3cyUyRm1hcCUyMiUyMGZyYW1lYm9yZGVyJTNEJTIyMCUyMiUyMGFsbG93ZnVsbHNjcmVlbiUzRSUzQyUyRmlmcmFtZSUzRQ==[/vc_raw_html][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1534691928040-02d2971b-12c6-8″ taxonomies=”9044″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]